The last bohemian, enthralled by Liverpool

The life of Augustus John, the latest Covid-19 data, and some personal graffiti from the 1950s

Good morning readers, and welcome to the latest newsletter from The Post. Amazingly, there are now just over 2,300 of you on the list, and we are gearing up for our full launch in about six weeks.

Today’s newsletter has a bit of a cultural focus, including great recommendations for things to do and see locally in the next fortnight and a lovely piece by Dani Cole about Augustus John, an artist whose paintings are on show for another week at the Lady Lever Gallery in Port Sunlight Village.

Huge thanks to the many of you who have recommended The Post to friends and helped us to grow our email list much faster than we expected during our soft-launch phase. If you think someone you know might like the kind of journalism we are doing, please just forward this email to them and encourage them to sign up.

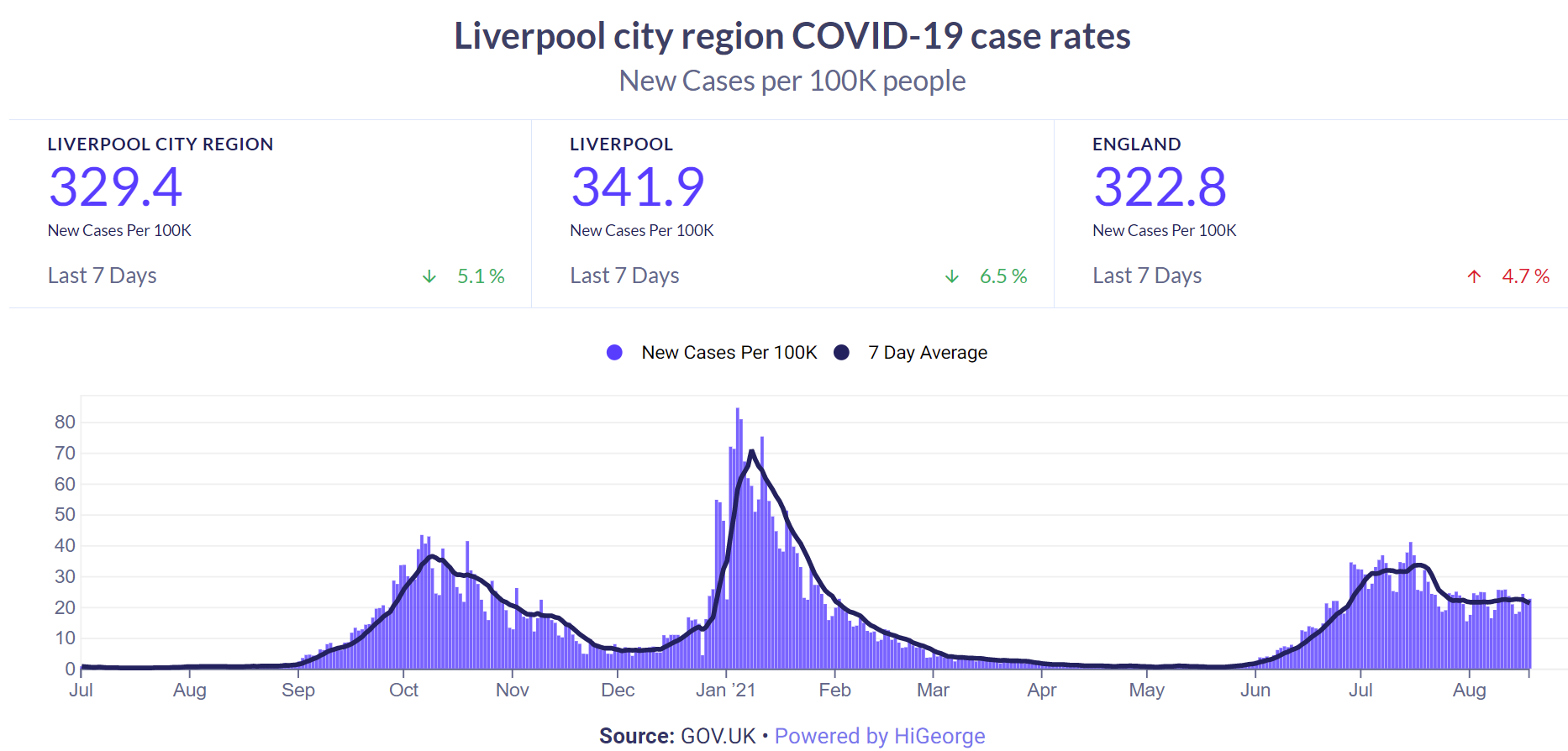

Covid-19 update

- Cases: The number of new Covid-19 infections has been pretty flat since the start of the month in the Liverpool City Region — not going up or down much. The most recent case rate is 329.4, down 5.1% versus the previous week. The case rate across England is fractionally lower — 322.8, up 4.7%. Liverpool itself has a case rate of 341.4, down 6.5% in a week, and the other boroughs of the city region have very similar rates, without much variation between them.

- Hospitalisations: The last time we got an update from hospitals, there were 230 Covid-19 patients in the city region’s hospitals — that was updated at the beginning of last week and it had risen slightly from 195 a month before. The number of Covid patients on mechanical ventilation was 32 last week, compared to 26 a month before.

- Vaccinations: Just over 66% of adults in the city region have had two doses of a Covid vaccine when the numbers were updated at the start of last week, with the Wirral leading the way on 73.8% and Liverpool way behind on 55.9%. Liverpool has a much younger population than the other boroughs and has the lowest proportion of under-35s doubled jabbed: just 27.2% compared to 39% in the Wirral.

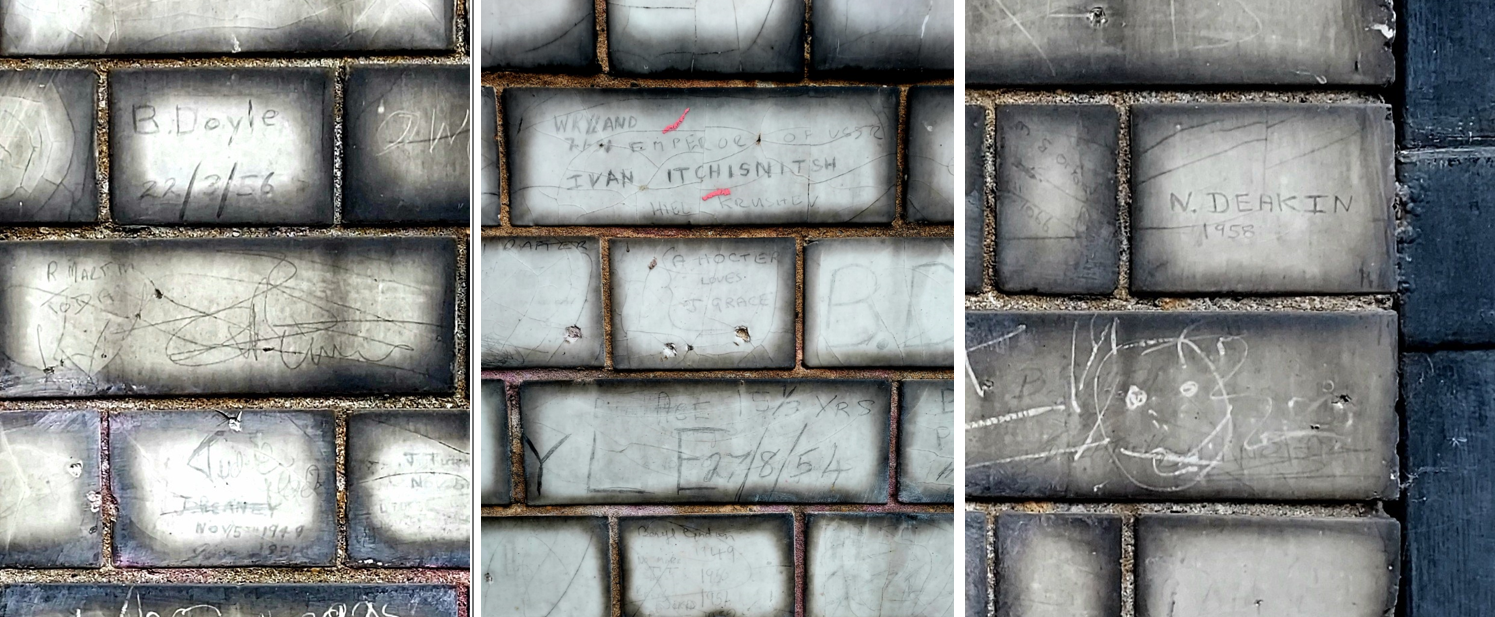

Under the bridge: Mystery of the 1950s graffiti

Thanks to Post reader Billy Dean for this letter. He writes:

It is not your standard graffiti, that’s for sure. The names, dates signatures and drawings on the tiled walls underneath the railway bridge, capture moments from the 1950s. Located at the Mossley Hill end of Queens Drive in South Liverpool, you could be forgiven for missing them. We can assume that these are the marks of young people from the local area. One possible explanation is that Liverpool College can be found just down the road and school kids may have wanted to leave their mark in celebration of leaving school. However, the dates show different times of the year, with the majority of them being from the 1950s.

If this was a local tradition, we might expect to see more names etched into the tiles and over a greater period of time. Do you recognise any of the names or know any more about the mystery of the 1950s graffiti?

Please write in if you know more. Just hit reply to this newsletter or email editor@livpost.co.uk.

Post Picks

Talk: On Wednesday (August 25th) Artist Aliza Nisenbaum will be in conversation with the NHS staff from Liverpool and the Wirral who were the subject of her paintings during the pandemic. Nisenbaum, who creates colourful works, is based in Los Angeles, and she painted a group of key workers over Zoom. Book tickets here.

Food: Try out the new Scandinavian store and cafe Skaus on Allerton Road. “Our concept is inspired by Scandinavian culture, seasonal cooking and Scouse hospitality,” says its founders Dan and Josh. They were featured on BBC’s ‘My Million Pound Menu’ in 2019 and their dishes are homemade. Details here.

Photography: Urban Goals is a project by Liverpool photographer Michael Kirkham, who set out to find football goals in deprived areas of the country, inspired by one in Toxteth. “It had ‘R.I.P Chedz’ spray-painted on the wall near it. That seemed so poignant; I decided I wanted to find a way to convey the aspirations of all the young people growing up in Liverpool, and the rest of urban Britain.” Read about it here.

Orchestra: The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra has announced its 2021-2022 season, and will be joined by Domingo Hindoyan as chief conductor. The first concert won’t take place until September 9th, but you can start booking tickets here.

Podcast: The Stories of our Times podcast has published a brilliant 3-part series about the dark history of Penrhyn Castle in north west Wales. The series, which naturally features Liverpool in its narrative, digs into what this stunning building tells us about Britain’s role in the slave trade and the sugar plantations of Jamaica. You can listen to it here.

Books: In anticipation of Sally Rooney’s new book Beautiful World, Where Are You, the Waterstones in Liverpool ONE will be holding a book club to discuss her hit novel Normal People on Tuesday August 31st. Book tickets here.

To tell us about a great event or opening for Post Picks, just email editor@livpost.co.uk.

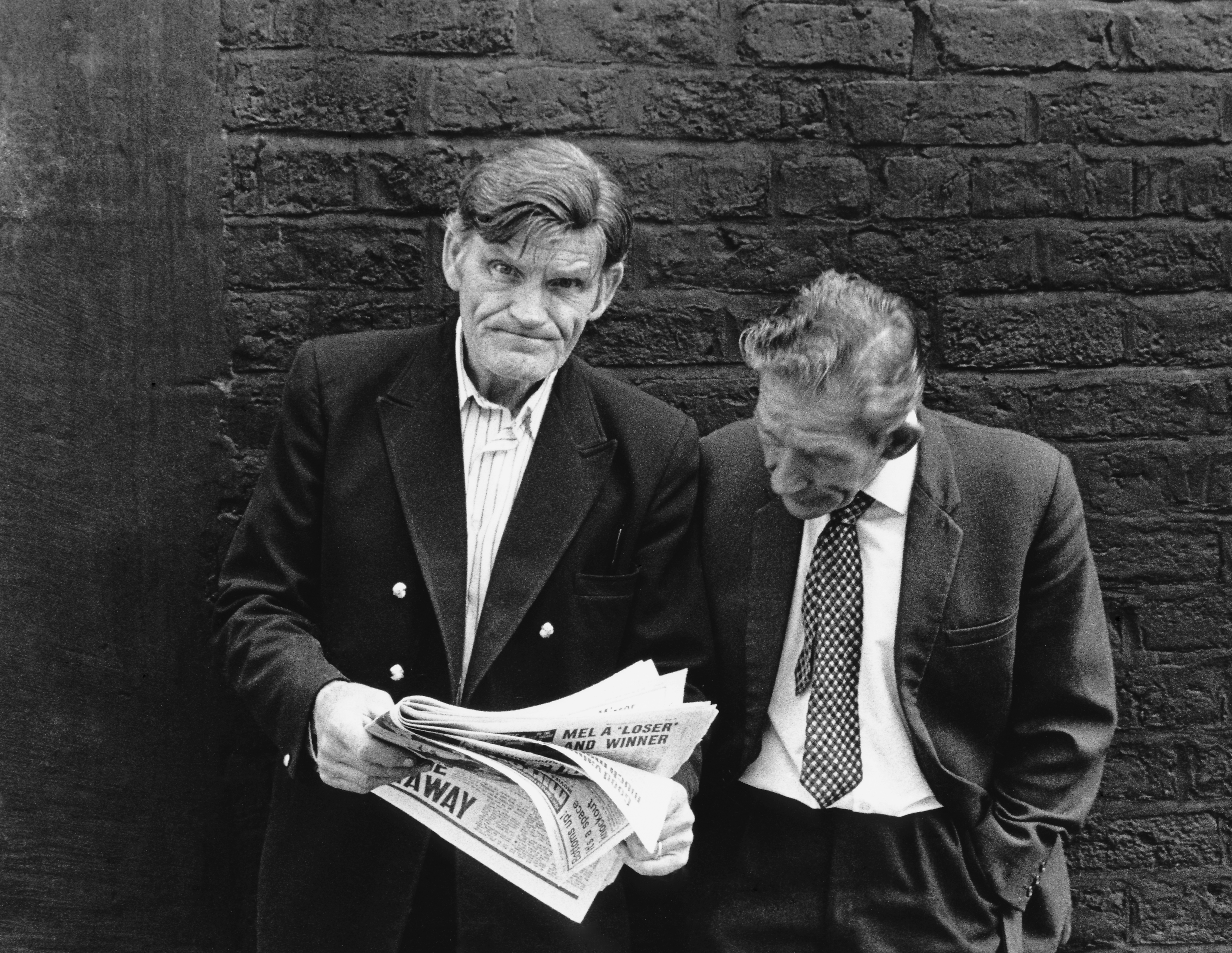

Two Merseyside men reading the Daily Mirror in 1968. Photo: Dave Fobister/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Our favourite reads

We enjoyed this feature in The Guardian about the creatives trying to lead a cultural renaissance on the Wirral. “This town was once grand and prosperous, and it needn’t be forgotten about and viewed as a pauper to Liverpool,” one of them says. “We wanted to have a venue, but also make people think differently about Birkenhead.”

“Could Neanderthals have been like hyaenas and wolves, where all adults hunt? Among recent hunter-gatherers, women as dominant lioness-style predators seem nonexistent.” We thought this was a fascinating piece from Rebecca Wragg Sykes in Aeon Magazine, who is a Palaeolithic archaeologist and honorary fellow at the University of Liverpool, in which she examines the lives of Neanderthal women.

Dorothy James, Barbara Murray and Marion Lloyd, Young Ladies of the Liverpool Blue Coat School, 1948, by Nora Heysen, 1911-2003 (Liverpool Blue Coat School).

— Brian Groom (@GroomB) 10:58 AM ∙ Aug 22, 2021

After Liverpool lost its UNESCO heritage status, this spirited article from SevenStreets makes a case for trying to balance the old with the new. “The stripping of our UNESCO status — blamed on years of development causing an ‘irreversible loss’ of our historic Victorian docks and mercantile heart — was anything but inevitable. New buildings don’t have to be anathema to heritage.”

We were interested to find this 2019 piece by Andrew Beattie in Liverpool Long Reads about regeneration in north Liverpool, which speaks to key players in the community, who were fighting back against “mishandled regeneration projects.” Beattie writes: “Broken promises, flogged-off family silver and vested interests have unified the community in their scepticism over schemes and projects that are seen as being parachuted in; something done to the community rather than with the community.”

“Riffing on the Latin piety of its name, some passengers will speak of taking a leap of faith. In truth, it is only a step, but it must be well-timed and placed lest you miss the platform of the cabin. Since the paternoster continues with or without you, you may well wish to mutter an Our Father.” This feature in Granta is a requiem to the Paternoster lift, which was first built in Liverpool in 1869.

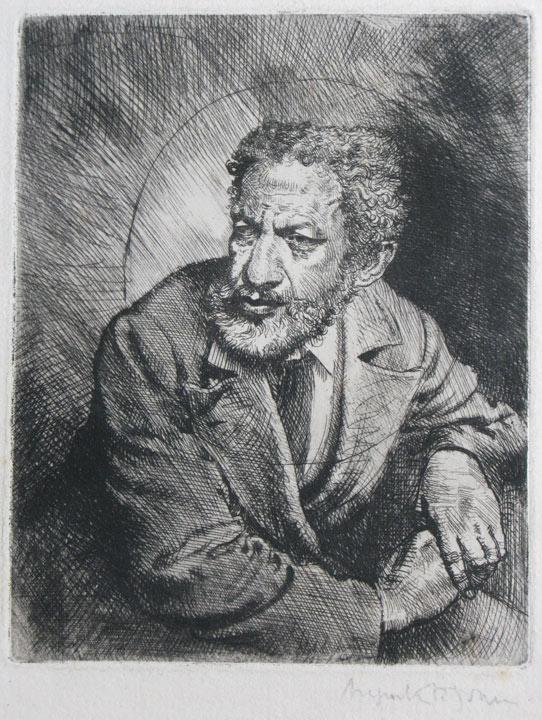

Exhibition: Rediscovering Augustus John

The Last Bohemian: Augustus John. Showing at Lady Lever Gallery until 30 August.

As he strode across the quad of the Liverpool School of Architecture and Applied Art, Augustus John drew the gaze of startled university staff. It was 1901, he was 23, and he had already cultivated an unconventional appearance: he was lithe, with a head of soft, long brown hair, a russet beard, and “large magnetic eyes.” The aviator Frederick Laws described him as having a “vigorous, swashbuckling personality.”

His shoes were unpolished and he was wearing a grey fisherman’s jersey and had golden rings in his ears, which must have glinted in the light. John had been warned that Liverpool was an ugly city, but instead it enthralled him. While others were repulsed by the Liverpool docks, he found them “wondrous” and “revelled in the spectacle of human diversity.”

Born in Tenby, Wales in 1878, John would come to be regarded as one of the most important portraits painters in Britain — supplanting John Singer Sargeant — and one of the greatest draughtsman. His sitters included members of the literary elites like William Butler Yeats (who initially hated his portrait, thinking it showed him as drunken and “disreputable”) and Dylan Thomas, about whom John said: “If you could have substituted an ice cream for a glass of beer, you might have mistaken his for a happy schoolboy out in the spring.”

He was drawn to people and Liverpool was rich in subjects. “If he met an interesting character, you knew the portrait of them was going to be fantastic,” says Alex Patterson, the curator of a brilliant show about John at Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village. The wasteground of Cabbage Hall near Aintree yielded “haberdashers, young serving-maids, ragamuffin children” and “all the cosmopolitan population” of the city. Liverpool stimulated him — in Augustus John: The New Biography, Michael Holroyd writes that John’s letters from his first year in the city “were congested with happiness.” The artist wrote to Michel Salaman: “Liverpool is a most gorgeous place.”

“He shook up the whole scene in Liverpool at the time,” Patterson says. John taught at the Art Sheds — the name given to the Liverpool School of Architecture and Applied Art — from 1901 to 1904, where they had “amazing classes of ironworks” and there was an atmosphere about the place.

The exhibition contains 40 works, including loose figure sketches, oil paintings and etchings. Many of them concentrate on John’s early works and reflect his time in Liverpool, with other paintings — such as those of Yeats, Thomas and the infamous ‘beheaded’ portrait of Lord Leverhulme — representing other key moments in the artist’s life. “I really wanted to bring in a lot of his unfinished works,” Patterson told The Post, referencing the early point of John’s career. “So you're actually seeing that side of him.” Patterson hopes the unfinished works will inspire aspiring artists and art students who visit the exhibition.

A number of paintings she had initially noted down for inclusion turned out to pose logistical barriers: “A lot of his early works, they’re enormous,” she says. “Some are wonderful and tiny — you have to work out what to put in.” There are a number of figure sketches, which John drew for his students as a demonstration — the lines are rapid, loose but still convey mastery. John didn’t think much of them. “He would just throw them on the floor, and as you can imagine, the students would jump and grab them,” she says. The sketches were saved and are now part of the exhibition.

She tells me that John’s time in the city marked a significant point in his career: he was just starting out, and it was here that his first etchings were made, wandering through the crowds to find his subjects. Included in the exhibition is Man From Barbados, an etching made in 1901-2 which was originally called The Mulatto, a now-derogatory term that was used to describe people of white European and black heritage. The etching feels special — Liverpool has one of the oldest black communities in Britain. It is small, finely detailed, and shows a man with short curly hair and a furrowed brow.

John’s time in Liverpool was also important as it was here that he met John Samson, a librarian, linguist, and Romany scholar. John was Samson’s “most eclectic disciple” and he was soon able to pick up the English dialect of Romany thanks to Samson, who also introduced John to the free-spiritedness of Gypsy culture. From 1937 until his death in 1961, John was the President of the Gypsy Lore Society in Liverpool.

“He was very spontaneous as a person, that was the kind of character he was,” says Patterson. In his book, Holroyd writes that when John was a boy, one day he leapt onto the back of an untethered horse, and the two thundered across open ground, the young John slowly sliding off the creature until his arms were wrapped around its neck.

Later John would be living in a ménage à trois, travelling in a caravan on Dartmoor in Devon with his wife Ida and mistress Dorothy ‘Dorelia’ McNeill and their children. He painted both women, and their portraits are included in the exhibition. Ida is depicted as a gypsy ‘Merikli’ (which means ‘ornament worn round the neck, gem, bead, especially coral’).

It was his first critical success, voted the New English Art Club’s Picture of the Year in 1902. The painting is warm, and her face is touched by soft light as she looks out at the viewer; the basket of flowers and bright red cherries in her hand are vivid against the dark tones of the background.

The Last Bohemian: Augustus John is showing at Lady Lever Gallery until 30 August. Details here.

Comments

Latest

Last minute drama, local revamps and Liverpool Doc Club

Is Williamson Square Liverpool's own Times Square?

A chaotic afternoon with Reform’s newest Wirral recruits

As Chinese car-making booms, Liverpool spots a chance to reindustrialise

The last bohemian, enthralled by Liverpool

The life of Augustus John, the latest Covid-19 data, and some personal graffiti from the 1950s