Millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas to be piped under Liverpool Bay

"Carbon capture" is coming to Merseyside. So why aren't green activists happy?

The Post isn’t messing around. Just yesterday, we published an exclusive investigation into a London fund manager selling homes from under Liverpool’s residents. Today, we’re delving into the biggest infrastructural project the North West has seen in over a century — not to mention the UK government itself. But for us to continue our blistering start to 2026 and holding decision-makers to account, we need your help. The Post operates on a reader-funded model, and we couldn’t do what we do without you. Become a member today for just £1 a week for the first three months.

Last week was the first time most residents of the Wirral had even heard of “Peak Cluster”. Rifling through the post on the doormat, many took a few moments to work out what possible relevance cement plants in the Peak District could have to their lives.

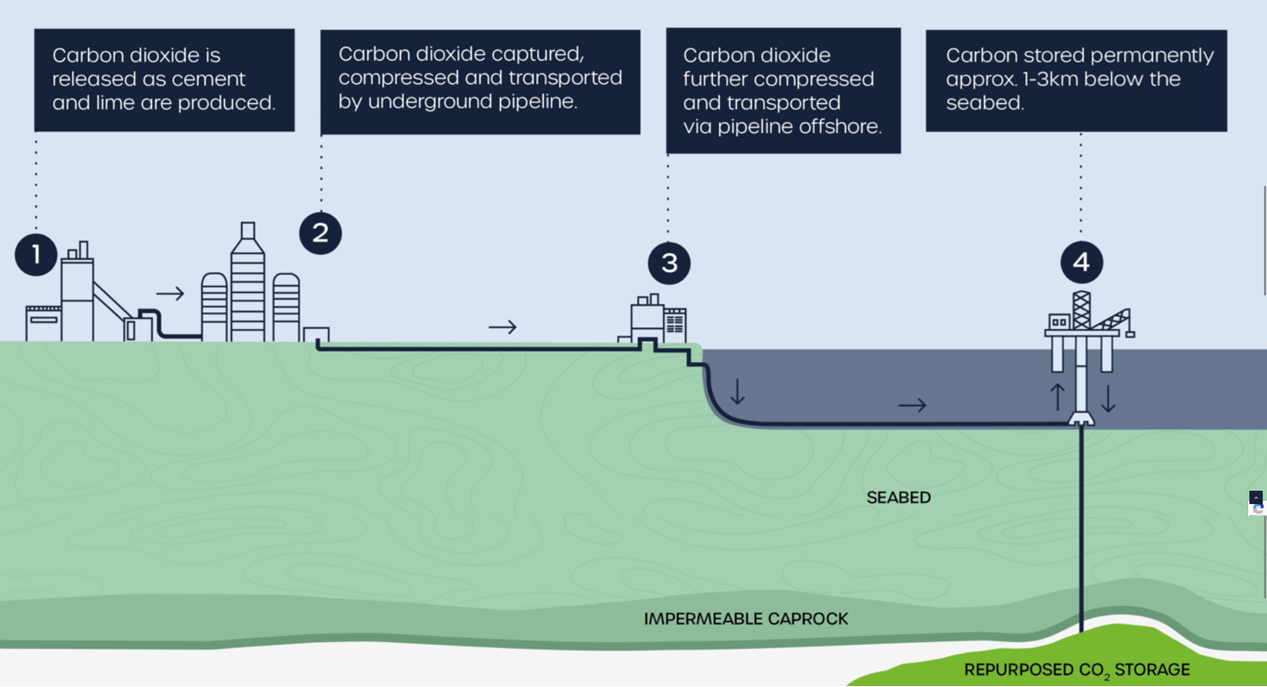

But the pamphlet, from “the world’s largest cement decarbonisation project” helpfully included a graphic. Cement production generates huge amounts of CO₂ — around 8% of man-made emissions globally. And the Peak District, with its vast deposits of limestone, is a hub for UK cement production. At the moment, that CO₂ floats up into the atmosphere, where it unhappily contributes to global warming.

Peak Cluster had a better plan: collect the CO₂, condense it to a liquid-like "supercritical" state, and shoot it through pipelines all the way to, and under, the Wirral peninsula, before taking a handbrake turn up towards the coast off Morecambe Bay, where the gas will be stored deep under the seabed.

What do you do when you’ve just been told a huge pipeline carrying CO₂ is going to run near or underneath your home? Take to Facebook, of course. A trawl of local groups shows that residents have plenty of questions. Just what does “carbon capture and storage” (CCS) entail? Are these pipes safe? Why do they have to run beneath the Wirral? And is packing millions of tonnes of a greenhouse gas under the sea really advisable?

Until now, CCS hasn’t had much attention locally. I became aware of it in October 2024, when the UK government pledged £22 billion for two CCS schemes: Teesside Net Zero in the North East and what became HyNet in the North West, a collaboration between EET Fuels, Cadent Gas and Eni.

HyNet — which plans to put CCS into operation in 2028 — is looking to shoot the CO₂ through new and existing repurposed gas pipes in Flintshire and store it even closer to home: the depleted Hamilton gas field under Liverpool Bay. HyNet is also promoting the replacement of natural gas — the kind you use to heat your home — with hydrogen, so that no more carbon dioxide is produced as a byproduct.

A year after the government announcement, I’m passed the phone number for a Mark Fleming, who describes himself as a whistleblower.

“I’m from Reform, so I have a particular political position,” Fleming says, almost confessionally. In fact, he’s spokesperson for the party’s cost-cutting ‘Wirral DOGE’ team — inspired by Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency. Before his political activism, though, Fleming earned a Masters in chemistry. While he admits this does not make him an expert, he says more qualified people he's consulted cannot argue with his assertions: that HyNet’s injection of carbon dioxide offshore will create a “toxic time bomb” under Liverpool Bay. Once the CO₂ leaks — and the evidence, Fleming says, is that it will — marine life will be threatened “on a massive scale.”

“We’re talking about injecting hundreds of million tonnes of carbon dioxide into this hole in the ground, under the sea,” he says. “If you were to fill two-litre Coca Cola bottles with that much CO₂, you’d have to stack them one on top of another, to the height of the Radio City Tower, from Southport all the way down to Colwyn Bay.”

Later that night, I find myself brooding over Fleming’s assertions. Even if they sound outlandish, I find him affable, honest, passionate and, most importantly, strong on detail. Fighting the instinct to dismiss what he’s said leads me, months later, to the ancient hinterlands of Merseyside and Cheshire, via hundreds of pages of scientific papers, chats with activists, consultations with academics, perusals of US newspapers and departmental reports, and probably two dozen press releases from politicians.

Welcome to The Post. We’re Liverpool's quality newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Post every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

On a cold January morning, a south-easterly wind shakes the branches and whips the fallen leaves into eddies. The playground is empty; the tall Gothic church to my right abandoned; the Entish oak to my left impossibly gnarled. Only about 250 people live in Thornton-le-Moors, but some features of St Mary’s Church date back to the 14th century. Not far from here is the bare ruined choir of Stanlaw Abbey, built by Cistercian monks 800 years ago on a low-lying promontory striking into the Mersey estuary. A trio of German shepherds bark at me from a nearby farm as I walk among the gravestones and yew trees of the churchyard.

Beyond the line of denuded trees at the playground’s edge is something else — something startlingly modern. It encompasses the abbey site and dominates Thornton-le-Moors and the neighbouring, equally medieval villages of Elton and Ince: the Stanlow oil refinery.

Driving around Stanlow’s tanks, heaters, distillation units, towers and drums a hundred years after its construction, you get a sense of a city vast but not built for humans. Its chimneys dwarf the parapeted belltower of St Mary’s: they’re fitted with blinking red lights to ward off low-flying aircraft; and the naked orange glow of its flare stacks burn hydrocarbons in perpetuity. Though to outsiders Stanlow looks like an incursion of Mordor into the Shire, the local population are ambivalent. My mum’s late husband got his first job there, cleaning out vats (without proper PPE). He used to describe with disturbed fascination the strange blue ash that would descend on his nearby village from the refinery’s direction.

In 2022, Essar — who bought Stanlow from Shell in 2011 — announced plans to decarbonise it, pledging £360 million towards the construction of a carbon capture and storage (CCS) facility.

Alongside their HyNet partners, Cadent Gas and Eni, Essar say that the CCS facility at Stanlow will capture 0.81 million tons of carbon dioxide each year after completion in 2027. That’s 40% of all Stanlow emissions, or the equivalent of taking 400,000 cars off the road.

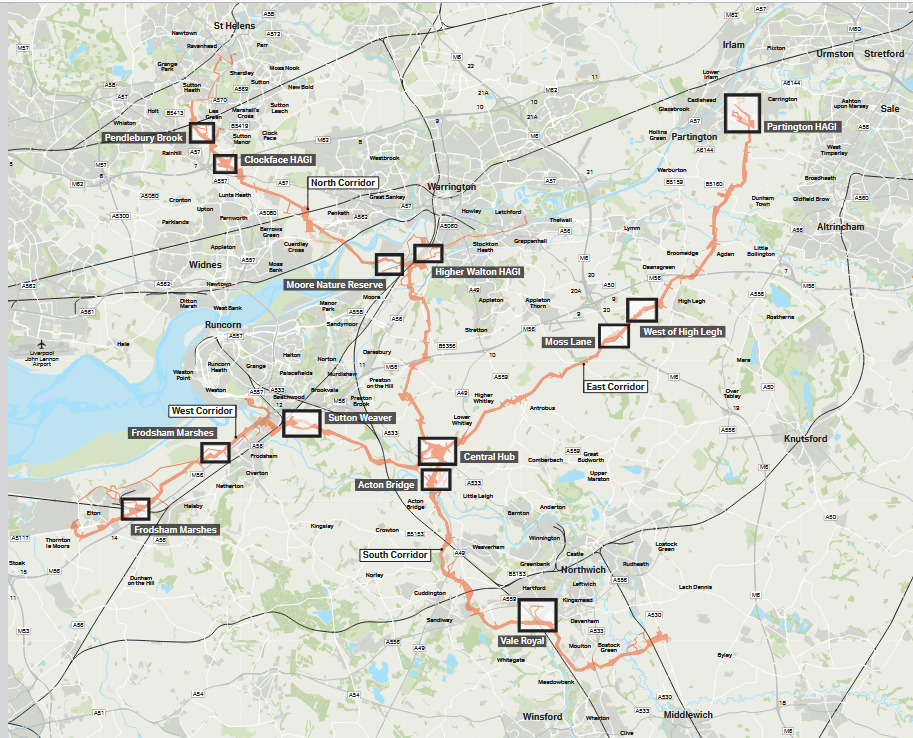

If your eyes glazed over that last paragraph’s zeroes, abbreviations, percentages and project names, picture this: a network of underground pipes funnelling carbon dioxide and hydrogen all around the North West, from here at Thornton-le-Moors and Winsford in Cheshire all the way up to St Helens and Partington in Merseyside and Greater Manchester respectively.

All in all, it’s a massive infrastructural project, the beneficiary of billions of pounds of central government money and on a scale unlike anything the region has seen for a century. If HyNet’s claims are borne out, the North West will see 6,000 new jobs, 2 million fewer tonnes of carbon in the atmosphere, and £17 billion extra into its economy by 2050.

That all sounds good, but some locals are sceptical. Not least because, when it comes to HyNet, there’s history.

Some years ago, Kate Grannell, a resident of Whitby, one of Ellesmere Port’s suburbs, led a campaign against Cadent, another HyNet component company. Back in 2022, Whitby was set to become a “hydrogen village” and Kate’s home was one of 2,000 earmarked to have its supply of natural gas turned off. Residents had concerns: although the government and fuel companies say it can be made safe, hydrogen is both more leaky and combustible than natural gas. They also resented being treated as “guinea pigs”, as one of Kate’s neighbours put it to the BBC.

“It was really frustrating and condescending,” Kate, who says she has been involved in the local Green Party, recounts. “Like, ‘we’re the experts, and this is what’s best for you, and although we’re running “consultations” or whatever, you don’t really get a say’. And when people talk like that, and only give you one side of the story, it makes you suspicious, doesn’t it?”

When the resistance to Cadent’s hydrogen village project began, it was just two or three concerned Whitbyites against the company responsible for the largest natural gas distribution network in the United Kingdom. Kate describes when, after months of raising awareness, 400 people turned up at a town hall meeting wearing T-shirts saying NO TO HYDROGEN:

“It was like one of those movie moments,” she tells me, becoming teary-eyed. “For all of these people to unite and stand up for something that they believed in… it’s one of the best things I’ve ever done with my life.” After eighteen months of campaigning, Cadent backed down.

Having been hostile to hydrogen, what’s Kate’s view on the new carbon capture and storage proposals?

“I think it’s a scam,” says Kate.

Welcome to The Post. We’re Liverpool's quality newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Post every week.

She’s not the only one. Labour’s Carolyn Thomas is a Member of the Senedd for North Wales; when HyNet was approved in 2024, Thomas told BBC Radio Wales Breakfast that her country was going to be used as an “exhaust pipe”. This was a break with her own party’s hierarchy: HyNet has been backed by energy secretary Ed Miliband, who first announced the plan to develop carbon capture sites in 2009.

Since then, Thomas has detailed her concerns about HyNet’s carbon dioxide pipeline before the Senedd: that it runs under 26 watercourses, including the River Dee, not to mention agricultural land, communities, ancient hedgerows, conservation sites, badger sets and children’s play areas.

Thomas mentions two previous examples of CCS projects that haven’t gone to plan: one off the coast of Norway, and another in Mississippi. She also sends me “Deep Trouble: The Risks of Offshore Carbon Capture and Storage”, a report by the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL).

“Deep Trouble” goes into more detail on both case studies. The Norwegian example was at the offshore gas field Sleipnir, the world’s first true CCS operation, which began in 1996. There, the petroleum company Statoil began capturing carbon dioxide and injecting it into saline reservoirs beneath the North Sea in order to avoid paying the Norwegian CO₂ tax introduced five years earlier.

At Sleipnir — named after the Norse god Odin’s eight-legged horse — “geologists failed to accurately predict how the injected CO₂ would behave underground.” The carbon dioxide migrated upwards into an unintended layer of the subsurface.

It’s worth noting that no CO₂ was leaked at Sleipnir. And “Deep Trouble” is not a peer-reviewed academic paper: its authors are climate journalists, not scientists. Their main source on Sleipnir is a study by Grant Hauber, an energy finance analyst with a background in engineering, for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

When I later mention IEEFA to Stuart Haszeldine, a professor of CCS at the University of Edinburgh, he begins snorting and scoffing before I can even finish the sentence. “It’s basically an anti-carbon organisation. Fair enough, but you can’t always just go by the worst possible case.”

Haszeldine sounds tired, which he attributes to a day of “spinning plates”. But perhaps he’s just weary of journalists asking him these kinds of ignorant questions. About the claim that the behaviour of CO₂ at Sleipnir was unpredictable, he says “that just isn’t true. Must be about 20 million tonnes they’ve injected, and that's worked perfectly. What happened was the sandstone was more layered than we anticipated when we started injecting the CO₂.” He explains that scientists later discovered a small tongue of sandstone extending up into the mud and rock, which stopped the CO₂ in place. “They [critics] claim there was a leak from the top of the sandstone, which is totally not true, and actually is lying.” (NB: neither IEEFA nor CIEL’s reports said anything about a leak.)

As for the cost, while £22 billion sounds like a lot of money, Professor Haszeldine is quick to argue that it’s not that much over 20+ years. “Between 60 million people, I think I worked it out as a packet of crisps a week per person,” he says dryly. I can never decide if these conceptual aids involving coke bottles or crisp packets help or hinder my understanding.

The pipeline at Satartia in Mississippi, on the other hand, didn’t leak but exploded, hospitalising 45 people. On this matter, I first speak to Dr Andrew Boswell, a consultant for Climate Emergency Science Law, who has led the so far unsuccessful legal challenge against the Teesside Net Zero carbon capture project. Cheery and gregarious, Dr Boswell tells me he is not against CCS technology per se, but that the safety standards of the Teesside scheme are not up to scratch. He directs me to a piece in the Des Moines Register about the Satartia incident.

The Register article tells me that the 24-inch pipeline carrying liquid carbon dioxide ruptured after two months of rain caused soil around the pipeline to slide and a pipe weld to break. The explosion of carbon dioxide and dry ice — the solid form of CO₂, produced when the gas is exposed to a drop in temperature and low pressure – sent a plume towards the nearby village, and emergency services evacuated the area of around 200 people due to the risk of asphyxiation.

An NPR report goes into further detail. Witnesses heard a boom and saw a large white cloud shooting into the sky. Victims lying on the ground “shaking and unable to breathe.” First responders were baffled. The emergency director for the county is quoted as saying, “It looked like you were going through the zombie apocalypse."

But there was another problem. “The emergency vehicles going towards the cloud just stopped,” Dr Boswell says. “It sort of asphyxiates engines as well: there's not enough oxygen to burn petrol.” This claim is supported by a Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration report, which records several vehicle engine issues of individuals in the vicinity of the migrating CO₂ cloud.

“The implications for a more densely populated area like the Wirral is that emergency services need to be highly coordinated on this,” Boswell says. For instance, “they need to know that if they’re responding to an incident, they may need electric vehicles. And these pipes need to be highly monitored for leaks so they can respond quickly without relying on locals spotting it.”

“You’re never going to get a zero accident record,” Professor Haszeldine says when I bring up the Satartia case, as well as another incident in (you couldn’t make this up) Sulphur, Louisiana. “In the United States they’ve been pumping supercritical CO₂ since 1972, and the accident rate is better than with oil and gas. So that’s a straightforward statement for you.”

“We’ve just seen a train crash in Spain,” Professor Haszeldine continues, referencing the recent accident near Barcelona. “If forty people die, that’s not going to stop people getting the train tomorrow.”

Whether the people of Cheshire and Merseyside agree with that logic is not yet known. Last year, HyNot, a local campaign group, brought a legal challenge against HyNet calling for a judicial review. The High Court rejected the challenge in October, a decision which HyNot have now appealed. But HyNot’s press release neatly summarises the objections against CCS and hydrogen: that it’s costly, that it’s potentially dangerous, and that it is a lifeline for fossil fuel companies like EET, Cadent and Eni when the UK should be switching to renewables, home insulation and heat pumps.

The Post put these concerns to the UK government’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ), the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority (LCRCA) — who have wholeheartedly endorsed the CCS project — and HyNet themselves. Both DESNZ and LCRCA declined to go into detail regarding the incidents in Norway and the USA, but did issue statements.

"Carbon capture, usage and storage is vital for Britain's clean energy future, and the Climate Change Committee describes it as a 'necessity not an option' for reaching our climate goals,” a DESNZ spokesperson said. “We are delivering first of a kind carbon capture projects in the UK, backed by £9.4 billion over this parliament — supporting thousands of jobs across the country and reigniting our industrial heartlands.”

“The need to tackle carbon emissions and transition away from fossil fuels is clear and it is vital that the UK explores all technological approaches that could help reach that goal,” an LCRCA spokesperson told The Post. “We have been supportive of both of these projects on the basis that CCS could be transformative in the fight against climate change and in supporting our energy intensive industries.” LCRCA were keen to stress they do not fund or have any supervisory responsibility for either HyNet or Peak Cluster.

HyNet told The Post that CCS is not a life support for fossil fuel companies but “a readily available solution to abate emissions from industrial activities that currently have no decarbonisation alternative.” The spokesperson also contextualised the government’s multi-billion pound pledge in 2024 as an outlay over 25 years. They also defended the safety of both piping and storage, and cited a study published in 2018 that said: “for [CCS] sites managed correctly, over 98% of CO₂ remains permanently stored over 10,000 years”. The spokesperson also challenged the characterisation of the Satartia incident as “an explosion”, saying that unlike oil or natural gas, CO₂ is not flammable and denied that the rupture — caused by a landslide — had anything to do with the infrastructure.

Proponents of CCS like Professor Haszeldine say that the cost of not embracing these measures will be a false economy, it’s not all that expensive to begin with, the process has a good accident rate, and incorporating it as part of a longer-term green strategy is wiser than just switching off fossil carbon extraction altogether.

“We already tried that already when Russia invaded Ukraine,” Haszeldine says. “We took 5% out of the global supply and the price of gas tripled.”

Has there been scaremongering about CCS technology?

“Yes,” the professor says, unequivocally.

As a society, we’ve concluded that transporting highly flammable natural gas by pipelines is a risk we’re willing to take. The CO₂ pipelines purport to have a much more beneficial purpose — keeping a lid on greenhouse gas emissions. Maybe one day, they’ll seem just as normal. At a consultation meeting in Hoylake at 1pm today, residents of the Wirral will have the chance to ask their questions or express their objections. They’ll hope their experience doesn’t match Whitby’s when dealing with Cadent.

“To anyone who calls us NIMBYs — excuse my language, but just eff off,” Kate tells me. “We didn’t ask for this. I’m just trying to live my life, okay?”

Thanks for reading today's investigation. Remember: The Post operates on a reader-funded model, and we couldn’t do what we do without you. Become a member today for just £1 a week for the first three months.

Comments

Latest

Punk rock and Paradise

What the Liverpool FC parade report doesn't say

The Post has a problem

Paul Conroy: the self-doubt driving Liverpool’s most acclaimed war photographer

Millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas to be piped under Liverpool Bay

"Carbon capture" is coming to Merseyside. So why aren't green activists happy?