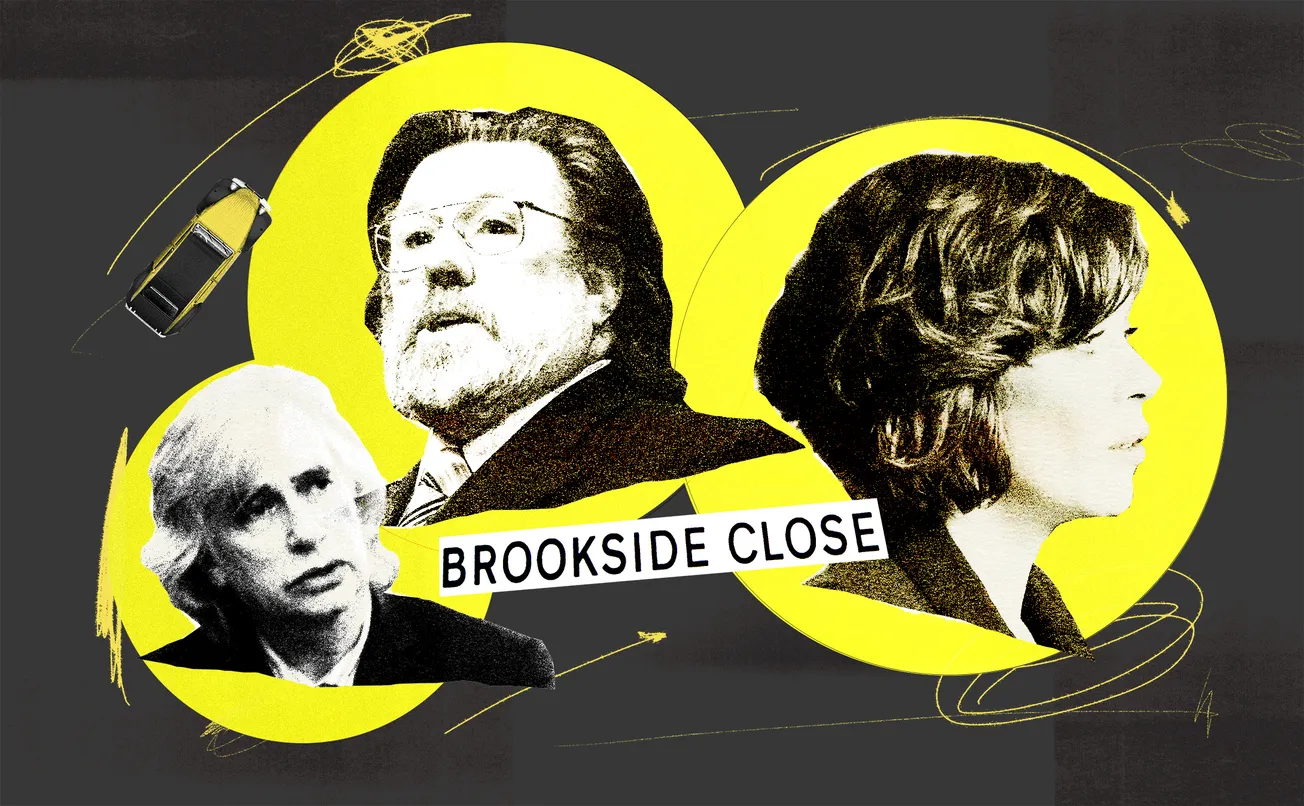

Why 'Brookie' matters

The bleeding-edge Scouse soap broke hearts and set records. But can it still be relevant in 2025?

I’m six years old, sitting on the couch at our home in Wallasey, vaguely aware we’re watching Brookside — or “Brookie”, as everyone calls it. On the telly, two mischievous-looking men are digging up a patio, watched by a concerned woman with a blonde perm. None realise the horror they are about to uncover.

“Aye, aye,” Eddie, the lead digger says, dropping his shovel and pawing through the disturbed earth to find something wrapped in black bin bags.

Eddie thinks he’s found something valuable, a treasure stashed away by another character. Jimmy, his mate with a widow’s peak and leather jacket, implores him to hurry up. Tearing eagerly through the vinyl, he suddenly recoils and draws back, a look of terror on his face.

The camera pulls away, but too late: we’ve already seen what he’s seen. A pale, partially decomposed human hand.

“I’m not sure if this is suitable,” my mum says, looking for the remote.

In the thirty years since, I’ve sometimes thought back to that moment, unconsciously modifying the memory each time until it’s Jimmy leading the dig, or a leprosy-white foot sticking out of the soil and plastic. I think I even added a scream by Rosie, Eddie’s wife, that never actually happened. So after watching the scene back on YouTube and realising how much I’d got wrong, I can’t exactly claim it’s a potent memory.

But something I’ve never forgotten is the strangeness. At a relatively early age, I was exposed to the likes of Alien and Terminator 2, so I was never too shocked by on-screen gore. But there’s a difference between watching science-fictional carnage, with its distancing, celluloid gloss, and this more domestic horror, cheaply filmed just over the River Mersey. Until 2003 when Brookie was cancelled, any Tuesday at 8pm could’ve been either a slice of relaxing escapism or like your first Fassbinder film, Ramsey Campbell short story or DMT hit: the frozen moment when everyone sees, as William Burroughs put it, what is on the end of every fork.

Next month, after a 22 year absence, Brookside will return — for a one-off crossover episode to celebrate the 30th anniversary of fellow Channel 4 soap Hollyoaks. The latter became Channel 4’s flagship continuing drama when Brookie ended, and even filmed on part of its predecessor’s former set, but as a daytime drama has never had the same impact or legacy. Watching back old Brookside episodes on STV Player, the Liverpool-set programme seems redolent of an earlier, much-lamented era of Channel 4, which offered a genuine cutting-edge alternative to BBC and ITV.

When the programme first aired in 1982, it was amidst a healthy marketplace of extant soap operas. The mighty Coronation Street, broadcast since 1960, already offered audiences Northern wit and urban working-class whimsy; Emmerdale Farm, with its bucolic setting, had been going for ten years; and motel-set Crossroads provided plenty of shoestring-shot cliffhangers.

Brookside also wasn’t the television-viewing public’s first exposure to Merseyside. Z-Cars in the 60s and 70s was set in “Newton”, based on Kirkby. The Wackers, a risible ITV comedy about a Liverpudlian family, appeared — and, thankfully, disappeared — in 1975. Then there was Carla Lane and Myra Taylor’s The Liver Birds, albeit with its almost entirely non-Scouse cast. Perhaps more salient predecessors can be found among the BBC’s Play For Today archives – Scully’s New Year’s Eve (1978) and The Black Stuff (1980), both by Alan Bleasdale, had acquainted British audiences with Liverpool’s growing precariat class.

Like what you're reading? You can get two totally free editions of The Post every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below.

“Brookie started where Boys from the Blackstuff finished,” Louis Emerick tells me, generously giving up his time in between filming the new crossover episode. He played Mick Johnson, a character who garnered the soap praise for resisting the stereotypical depiction of black men at the time. Mick was a responsible, working-class single father “who happened to be black,” as Emerick puts it.

Despite its predecessors, television producer Phil Redmond nevertheless saw a gap for a realistic, socially relevant, Liverpool-based soap that would challenge viewers with themes and storylines close to the raw knuckle of their everyday lives. So did Channel 4’s founding chief exec Jeremy Isaacs, who intelligently saw how ITV used “lowbrow” Coronation Street to draw eyes (and funding) to “highbrow” fare like Brideshead Revisited.

Brookie’s original set-up involved two households unlike in dignity but living side by side: the working-class, Catholic socialist Grants, who had moved from a run-down council estate, and the conservative, déclassé Collinses, recently downsized from a large Wirral house. This cast quickly grew to include the yuppie Huntingtons, the “scally” Taylors, and eventually a cavalcade of memorable characters including amiable window cleaner Sinbad (Michael Starke), loveable rogue Jimmy Corkhill (Dean Sullivan) and “bad lad” turned good Tim “Tinhead” O’Leary (Philip Olivier).

By the time six-year-old me watched the body of wifebeater Trevor Jordache (Bryan Murray) — buried by his wife Mandy (Sandra Maitland) and daughter Beth (Anna Friel) two years earlier with Sinbad’s help — being discovered under that patio, Brookside had already done its fair share of innovative storylines. Aside from covering domestic abuse and murder, it had also broken new ground by featuring the first pre-watershed lesbian kiss, almost a decade after having the first gay character on British television — both while section 28 was in full force.

What’s more, the people responded. At a time when Liverpool was barely emerging from periods of racial tension, Louis Emerick’s performances were so magnetic he found himself embraced across the city. When the writers did do a story about race, it involved Mick receiving abuse from bigoted petrol station owner George Webb (played by "lovely Ken MacDonald", as Emerick remembers him). Emerick says he found himself approached by an elderly white lady on Hanover Street. She felt obliged to exclaim, “Ay, Mick, we’re not all like that!”. To this day, people call Emerick by his character’s name, a testament to how enduring the soap still is in the Liverpudlian consciousness.

Redmond, reputedly so poor that he once had to borrow the tube fare from the BBC head of children's TV when he pitched Grange Hill, had gambled correctly on Brookside. At its height, the programme regularly drew seven million viewers.

As this popularity waned, that original mission statement of verisimilitude sometimes gave way to sensationalism, especially in later years. If you think the William Burroughs reference earlier was gratuitous, other subjects included in its 21-year run included rape, incest, religious cults, drug addiction, killer viruses, child murder and paedophilia. Characters who began life as everyday Liverpudlians became Sophoclean Scousers.

“But it was so funny, too!” says Judith, one reader who responded to our call to share memories of the programme. Like Coronation Street, no matter how dark Brookside got, every episode had a healthy dose of Northwestern patter to balance out the grimness. This was, of course, in part due to its writers: talent such as Joe Ainsworth, Kay Mellor, Roy Boulter, Jimmy McGovern and Frank Cottrell-Boyce, to name but a few, all worked on “the Close” in some capacity. But right from the start, Brookside availed itself of actors capable of delivering whip-sharp lines.

“Mickey could get you laughing your socks off,” Emerick says about Michael “Sinbad” Starke. “The first [unit director] would be yelling ‘action’, [Mickey] would straighten his face and I’d still be on the floor like a bag of shite laughing.”

“He could find the comedy in the darkest places,” Cottrell-Boyce tells me about Ricky Tomlinson, who played Grant family patriarch Bobby. “And he could find the weight in the lightest places, too. I learned quite quickly what a difference really good acting makes.”

I’m speaking to Cottrell-Boyce by phone on the windiest day of the year, so some of what we discuss is lost. But he tells me about what he learned from working on the soap early in his writing career.

“Because no soap opera is visually gorgeous, you have to make the words count,” he says, contrasting this with screenwriting for films, in which the story and visuals are paramount. Whereas on Brookside, “Dialogue was everything.”

Cottrell-Boyce later worked on Coronation Street, but describes that as much more “sedate” in comparison to Brookside, where writers, producers, actors, make-up artists, and set designers all worked cheek-by-jowl to throw episodes together rapidly. “There was a lot of shouting!” he says. “Let’s just say there were a lot of personalities. But that was good. It felt exciting. It was exciting!”

In the years since, Cottrell-Boyce — currently the country’s Children’s Laureate — has written award-winning films, novels, and even Danny Boyle's 2012 Olympics opening ceremony. (Which, incidentally, included Beth and Margaret's snog.) But working on Brookside “was a privilege, actually,” Cottrell-Boyce says. “I was very lucky. Talking to you has made me appreciate it!”

Some readers who got in touch are dismayed that the soap’s return next month will only be for one crossover episode with Hollyoaks rather than a continuing series. Others recall Brookside fondly for its daring willingness to confront issues and depict life warts-and-all.

“It’s the reason I do the job I do,” writes Rachel. Like me, the programme left a deep impression on her childhood. She describes watching the famous “siege” storyline: nurses Kate Moses and Sandra Maghie, along with hospital porter Pat Hancock, were held hostage in their shared house by a man who blamed the hospital where the three worked for his elderly mother's death. As the tension ratchets up, one of the women yells at their captor, disarming him verbally.

Aged just 12 years old, Rachel turned to her mother and eagerly asked what had just happened. “‘Ah, that’s psychology, that,’ she said,” Rachel recounts, igniting a fascination with the subject that later became professional.

“I’ve been a clinical psychologist for 25 years,” Rachel says, and “I do hold Phil Redmond and the writers of Brookside [partly] responsible. They dealt with gritty topics long before the current day soaps have, and with greater dexterity, sensitivity, daring and compassion. I aim to do the same with the stories I am trusted with.”

To be fair, much of Brookside’s DNA can be found in those other shows. Its willingness to be contemporary, relevant and confrontational helped convince the BBC that soap opera might fall within its purview after all, making it the father of EastEnders. By the time Brookside was cancelled — its viewing figures having fallen to a mere million — critic Mark Lawson wrote that it was also parent to Casualty, Holby City “and even the revamped Emmerdale”. It also launched the careers of genuine stars — not just Friel and Tomlinson, but also Sue Johnston and the late, great Katrin Cartlidge.

Perhaps a victim of its own success, Brookside has now been gone for longer than it was on telly. Reading the comments underneath the YouTube video of the infamous patio scene reveals an ambivalence about its cancellation:

“Brookside was and is the best soap opera ever to be broadcasted [sic] on British television,” says one fan.

“I do remember it getting fairly shit before it ended though,” replies another, beginning a debate about the soap's relative demerits in its final years.

Bringing it back full time, more than two decades after Jimmy famously scribbled that “d” at the end of the “Brookside Close” sign, would be risking anachronism. Do we really want a saga that once dealt with class war and grief-induced psychosis peppered with smart phones and references to Keir Starmer? Considering its influence, could Brookside have the capacity — or the productional will — to shock as it once did?

Judging by your responses, many of you will be shouting yes to those rhetorically-intended queries.

“Who knows?” says Emerick, not quite wanting to tempt fate. “The anticipation is through the roof right now, so we’ll have to see after [the episode] goes out. Stranger things have happened.”

But if a nostalgic one-off is all we get, the original Brookside’s legacy should be protected at all costs. For all its ups and downs, Brookie was a landmark moment in Liverpool’s social history. Never let the nation forget when a cheaply made Scouse soap opera led the way and changed British television forever.

Enjoyed this edition? You can get two totally free editions of The Post every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

Comments

Latest

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still play every Saturday

Does Liverpool have a ketamine problem?

The other Liverpool

Why 'Brookie' matters

The bleeding-edge Scouse soap broke hearts and set records. But can it still be relevant in 2025?