The other Liverpool

Our city has left its stamp globally — including its actual name. What's life like for Liverpudlians overseas?

Sometimes my mother will kiss my cheek to say goodbye and later I’ll find I’ve been going around town all day with a bright dab of lipstick on my face. Or else I’ll be talking to my boyfriend, who hails from Spain, and will hear my own distinct turns of phrase bubbling to the surface of his English. Then I think about how we’re all connected and none of us can avoid imprinting onto one another. This is a long way of saying: there are eight different locations called Liverpool in the United States, all named after the English city.

Of course, lots of North American sites have namesakes in England. But, Liverpool’s relationship with America seems particularly symbiotic, because the modern city exists mostly because of North America. Once a small fishing village, from the late 1600s onwards, Liverpool’s massive trade growth was fuelled by British colonies in North America and the West Indies. By the 19th century — when most of these places across the pond would have been named (or at least named by colonists settling there) — Liverpool had become wildly wealthy.

Perhaps the Liverpool trend was aspirational, with settlers hoping to replicate the same economic success the British original had enjoyed. Liverpool was also the biggest port for migrants heading to North America and Canada — between 1830 and 1930 over nine million people set sail bound for the continent — so it might just have been the name top of mind when they landed.

Today, the clutch of North American Liverpools are not all healthy — in fact, quite a few are ailing or dead. East Liverpool, Ohio, is doing okay but Liverpool, Illinois has a population of less than 100 people as of their 2020 census and Liverpool, Indiana doesn’t appear to exist anymore.

Still, there is something captivating about a glut of different Liverpools on the other side of the Atlantic. I wonder if it is like photocopying: if you copy a copy for long enough, you get these beautiful distortions. How will these Liverpools resemble the British rendition, if at all? How will they stray from the original? I propose to The Post that I explore. Not like Columbus, but like anybody with an internet connection and a dream — by conducting interviews with American-Liverpudlians from my living room, over Google Meet.

2026 has arrived and we’ve got a feeling we already know your resolutions: read more long form journalism; get to know your city that bit better; and support your local, independent press. Right?

Well in that case there’s no better time than now to take out an annual subscription to The Post. With a year-long subscription you get two months free, and you’ll know everything there is to know about Merseyside for the whole of the year. You’ll also get access to our entire back catalogue of scoops, stories, history-pieces and juicy features. Just click the button below.

My interest hones in on three: Liverpool, Texas; Liverpool, New York and Liverpool, Mississippi. Almost immediately Mississippi is out; after badgering various local historians in the area, it transpires there are no existing records relating to it. I cut my losses and switch focus to Texas.

Liverpool, Texas is so tiny it doesn’t have its own Facebook page or Craigslist, so I’m reduced to leaving wheedling messages on Texas-wide Facebook groups with titles like ‘Texas Everything’ or ‘We Love Texas’. It transpires these spaces are poisoned by the suspicion that the rest of the internet is trying to role-play as Texan and are littered with spiky posts to filter out the fakes (“If you really grew up in Texas, name a small town only locals would know”, “If you're truly from Texas shout out to where you grew up from”, etc.).

This preoccupation with authenticity and wannabes and squirrelling out fake Texans feels promising — very Liverpudlian, frankly — but nobody who moderates these groups ever approves my sad little posts appealing for interviewees. After an age, I manage to get hold of a governmental employee, a woman whose Southern accent is like syrup dripping directly into my ear. She promises to email with an update, but this phone call is the last I hear of her.

That just leaves Liverpool, New York, which already blows all the other Liverpools out of the water. For a start, their local government website has all the mod cons, including a functioning email address, and this is how I reach Liverpool’s deputy clerk and treasurer Sandra J. Callahan.

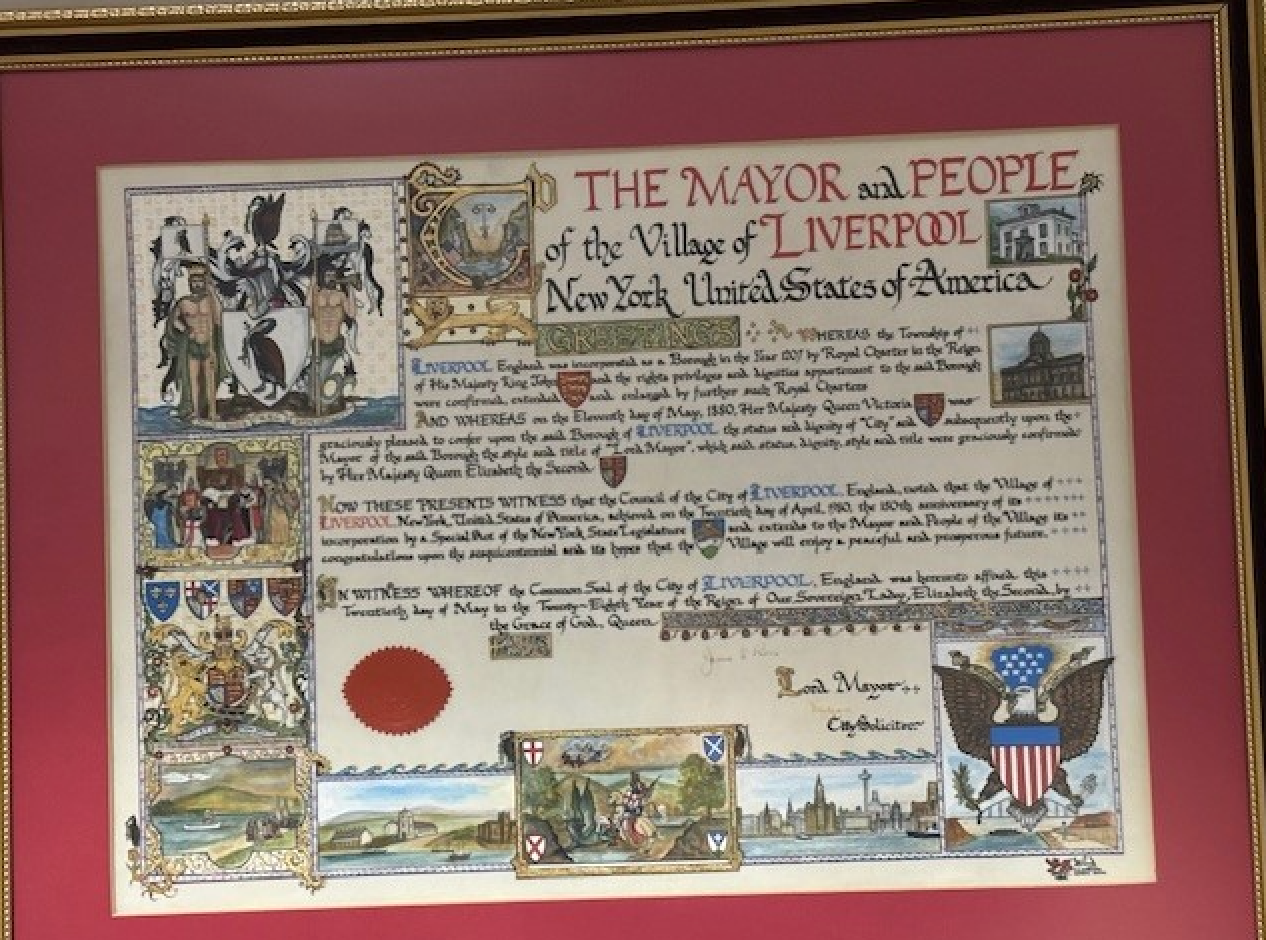

Sandra connects me with all sorts of people: a bonafide salaried village historian, Joan Cregg; the mayor, Stacy Finney, and villager Dawn Clarry. Photos and historical documents are forwarded. With a good deal of help from Joan, I piece together the history of the area.

Launching Liverpool, New York

Salt is the foundation of the Liverpool that sits two hours from the Canadian border. In the 1500s, a tribe of Native Americans, the Onondagas, settled close to a lake they called Gannentaa. In 1654, they had a visitor: a French-Quebecois Jesuit Father Simon Le Moyne who wowed the Onondagas by being able to speak their language.

The Onondagas mentioned a spring that they feared was home to an evil spirit, because of its reddish colour and strange taste. But Le Moyne recognised it for exactly what it was: a salt spring aka, liquid cash. The priest taught the Native Americans how to boil brine water to produce salt and reported these developments to the French. The French subsequently built a colony there, but the Native Americans began to resent their presence in the area, leading to a century of warfare.

By 1811, salt had brought more settlers to Liverpool and what was now called Onondaga Lake. Salt manufacturers set up shop too, producing up to 30,000 bushels annually.

Welcome to The Post. We’re Liverpool's quality newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Post every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

This is how she reckons Liverpool, NY became Liverpool. “We were given our name, Liverpool, from the New York state surveyor. He must have come to the area from the coastal cities that were brimming with immigrants and imported goods.” One of the stories about the origin of the village’s name claims that barrels of salt were shipped from Liverpool, England to the American colonies and had ‘Liverpool’ stamped on the top — since the salt the barrels contained was the highest quality, the name was seen as a sort of guarantee. Adopting the name might have been a sort of marketing gambit for the village, Joan speculates. They wanted to associate their salt with the English kind.

Other Liverpudlian industries followed, like willow weaving, and then much later, manufacturing, with General Electric and Coca Cola setting up shop.

This is history and fact but it is also misleading, since it makes Liverpool sound like one long row of factories. This is not exactly the present-tense version of the village, which is just one square mile large (so 43 New York Liverpools could fit into the English city) and home to around 2,600 people. The latter-day version of Liverpool is easy to explain if you’ve ever watched the 2000s mother-daughter TV series Gilmore Girls. This is because Liverpool is essentially Stars Hollow.

Village life

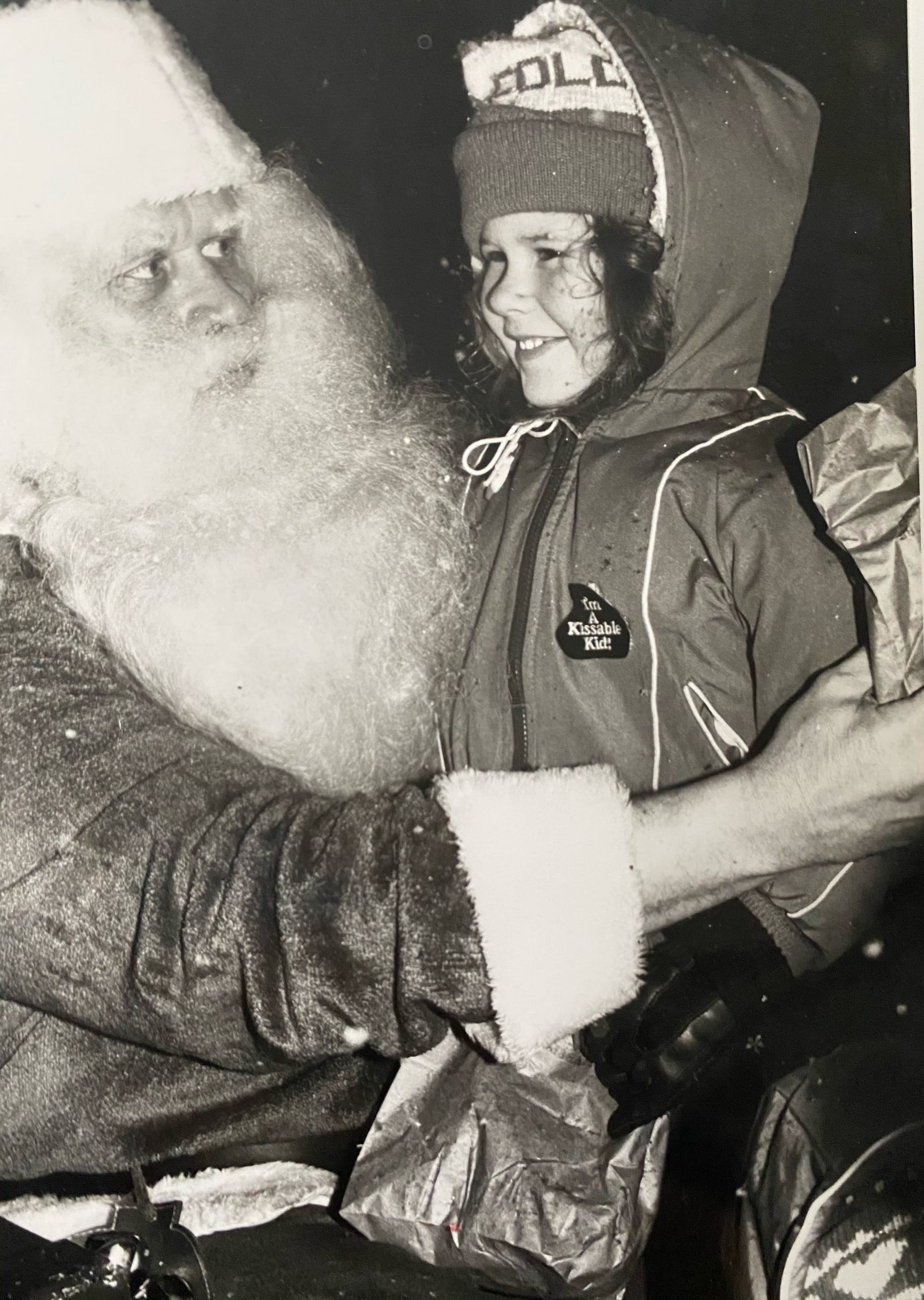

For those unacquainted with Gilmore Girls: Stars Hollow is a fictional but idyllic Connecticut town that is more philosophy than place. The show is a love letter to community, with town residents entangled in one another’s lives and brought together by quirky traditions. On talking to Dawn Clarry, 47, a local born and raised in Liverpool, she mentions a “tree lighting thing” the village does for Christmas.

When I pry, I discover there’s a whole day of activities: crafts at the library for the kids, storytime with Mrs Claus at a local bookstore. A bakery hands out free cookies, a cafe hands out free cocoa. There’s horse drawn wagon rides through the village, ice sculpture demonstrations and the tree is lit. It’s still not the end though, says Dawn, ticking off events on her fingers: Santa turns up with a fire truck’s worth of goody bags. Dawn’s father used to play him for three decades straight.

Continuity is Liverpool’s bread and butter. Dawn is still surrounded by people she’s known her whole life: she used to babysit one of the guidance counsellors at her daughter’s high school, she went to church with her daughter’s executive principal, and played volleyball with one of the secretaries at the school.

But even Liverpool is subject to change. Like the rest of America, it’s been buffeted by political winds— although not as one might imagine. Art teacher Stacy Finney, 50, grew up in Syracuse, the big city closest to Liverpool, and moved to the village in 2011, seeking better support for her son’s reading disability. Soon after their move, another resident went up to her husband, advising him to run for the board which runs Liverpool. “They were like, ‘but you need to be a registered Republican, because they’ll only hire Republicans.’”

Yet over the years, there’s been a shift: more gay pride flags on homes and, after Donald Trump’s election, yard signs proclaiming support for Black Lives Matter and women’s rights. Once her kids left home for university, Stacy suddenly had some extra time and couldn’t stop thinking about what she felt was the potential of the community.

In 2023, she ran as a Democrat in the first contested mayoral race the village had seen since Republican mayor Gary White took office, 14 years earlier, and won decisively.

Last year on The Post, we exposed corruption, abuse, held politicians to account and got nominated for two of the top journalism prizes in the country as a result. We're doing reporting no other paper in Merseyside is.

So why not become a full-time paying member and support our mission? You get four editions a week and right now, it costs just £1 a week for the first three months. That's a great deal for exceptional journalism.

While this was an impressive victory, being the mayor of Liverpool, NY doesn’t come with many powers. In England, the Liverpool city region metro mayor has the scope to manage local transport, set out plans for how land should be used to cater to housing, employment and transport needs, borrow money to deliver things like economic regeneration and housing; and set levies on local businesses, amongst others.

Meanwhile, in New York, Stacy has the deciding vote on the town board but most of her role involves fielding emails and phone calls like this one during her lunchtimes and after school. She’s particularly proud of instituting a pedestrian crossing at a road, something which has taken two and a half years to bring to fruition.

Whether or not Stacy is able to affect much change as mayor, the fact she was elected in the first place after years of Republican rule is evidence of a broader vibe shift. According to Dawn, while Liverpool was Republican in name for many years, as a small village, it wasn’t really political. “Everyone kind of got along. Traditionally, it's just always been Republican. Honest to God, because I think that's what people's parents were. When you would ask people, it was like, ‘I don't know, my parents were’.”

Now things feel different to Dawn, with newer residents who have relocated from outside the village seeming more scared of what the label Republican means today. “It’s not like the old days where, regardless if you were a Republican or Democrat, you may have disagreements, but you all got along. In this country now, we have a lot of discourse, maybe not of the healthiest kind. And that makes it really difficult.”

Lights, camera, action

Those newer residents are moving in thick and fast, a lot of them young families. Liverpool is considered a more and more desirable place to live, which is partly because it’s walkable — rare in America —and because the formerly polluted and stinking Onondaga Lake has been cleaned. A new computer chip factory is being built in a nearby town, which will increase demand for housing. Prices look set to rise, as is happening in Liverpool, UK.

Another shared feature is the fact that the village has become a film set (in 2022, the Liverpool Echo reported the city was now the second-most filmed site in the country after London). The old building that housed the school was up for sale and film company, American High, swooped in and bought it. Now they film short comedy sketches for social media and low-budget high school films there, as well as closing off streets or renting out empty houses in Liverpool to shoot in. Dawn describes the village having a love-hate relationship with the studio. “It’s been nice to have that in the village, but it can be very loud,” she says. “They shoot at night and they use large lights and generators,” she explains. “It’s not always enjoyable if you live near them.”

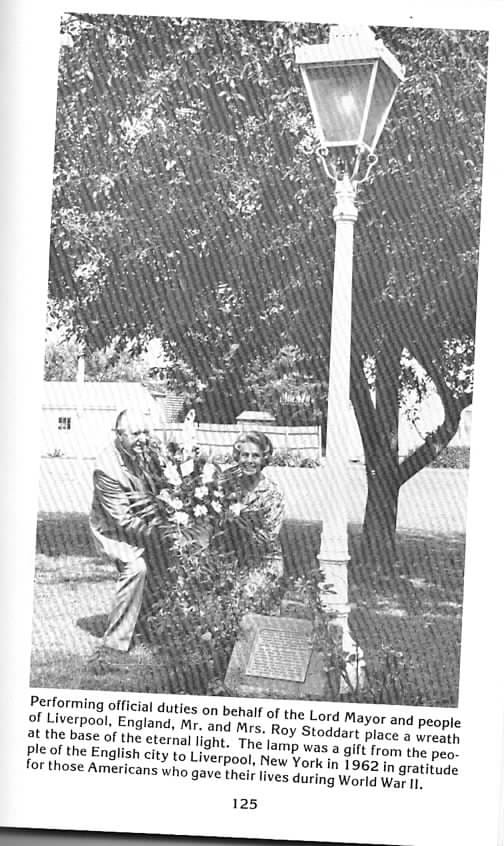

The mental comparisons between the original Liverpool and this little New York village seem my sole burden to bear. Over the course of my interviews, a humbling realisation dawns: nobody I speak to in Liverpool, New York seems to have ever thought much about the British Liverpool before. Nobody has visited. Interviewees strain to think of a favourite famous Liverpudlian, and inevitably resort to naming a Beatle. Joan does come up with one direct link — a street light gifted to the village by Liverpool, England as a post-war gift, in memory of the Americans who died in World War Two. But mostly, when I ask interviewees what they think connects the two places, there is not much in the way of a response.

This is both funny and not entirely illogical: why should they think about Liverpool, just because of the name? I rarely think of my important predecessors: popstar Sophie Ellis-Bextor, model-slash-writer Sophie Dahl or the anti-Nazi resistance fighter Sophie Scholl.

But what’s in a name, anyway? If Liverpool, NY was named after Liverpool, UK, what was the English Liverpool named after? There isn’t a single definitive answer to this, though it’s drawn from the Old English ‘Liver’ (which refers to the organ, but could also mean muddy) and ‘pol’, from pool or creek. One theory is that it was named after an inlet that once flowed in from the Mersey that was originally known as the Lyver Pool, which was where the first commercial wet dock was opened in 1715.

In the early 1800s, the Pool was considered too small to be useful anymore and was closed and filled in. These days, it’s been built over by Liverpool ONE, where brands like Levi Strauss & Co and Apple and Vans and Hollister hold court. Where once we settled North America, now they settle us. Instead of smallpox and shovels, they bring expensively marketed consumer goods.

The Lyver Pool may be gone, but there’s still a current, this time flowing both ways — carrying one excellent name and goods and scraps of history. The Liverpools across the ocean aren’t copies, but ripples: testimony to the mark the city left on the world.

If you enjoyed this article and you’re not yet a Post subscriber, here’s how to change that.

The Post produces great reporting and peerless writing about everything from education to politics, crime to conservation in Merseyside.

Our readers get all our stories direct to their email inbox, and are part of a brilliant community that sends us story ideas and debates the issues of the day in the comments. Just hit that button below to join up for free.

Comments

Latest

Just what is happening with Peak Cluster’s CO₂ pipeline?

A ‘stitch up’? How Wirral council bungled Big Heritage

Merseyside’s buses are coming back into public hands. Why not trains too?

From Jimmy McGovern to Len McCluskey: The household names rallying behind Writing On The Wall’s employees

The other Liverpool

Our city has left its stamp globally — including its actual name. What's life like for Liverpudlians overseas?