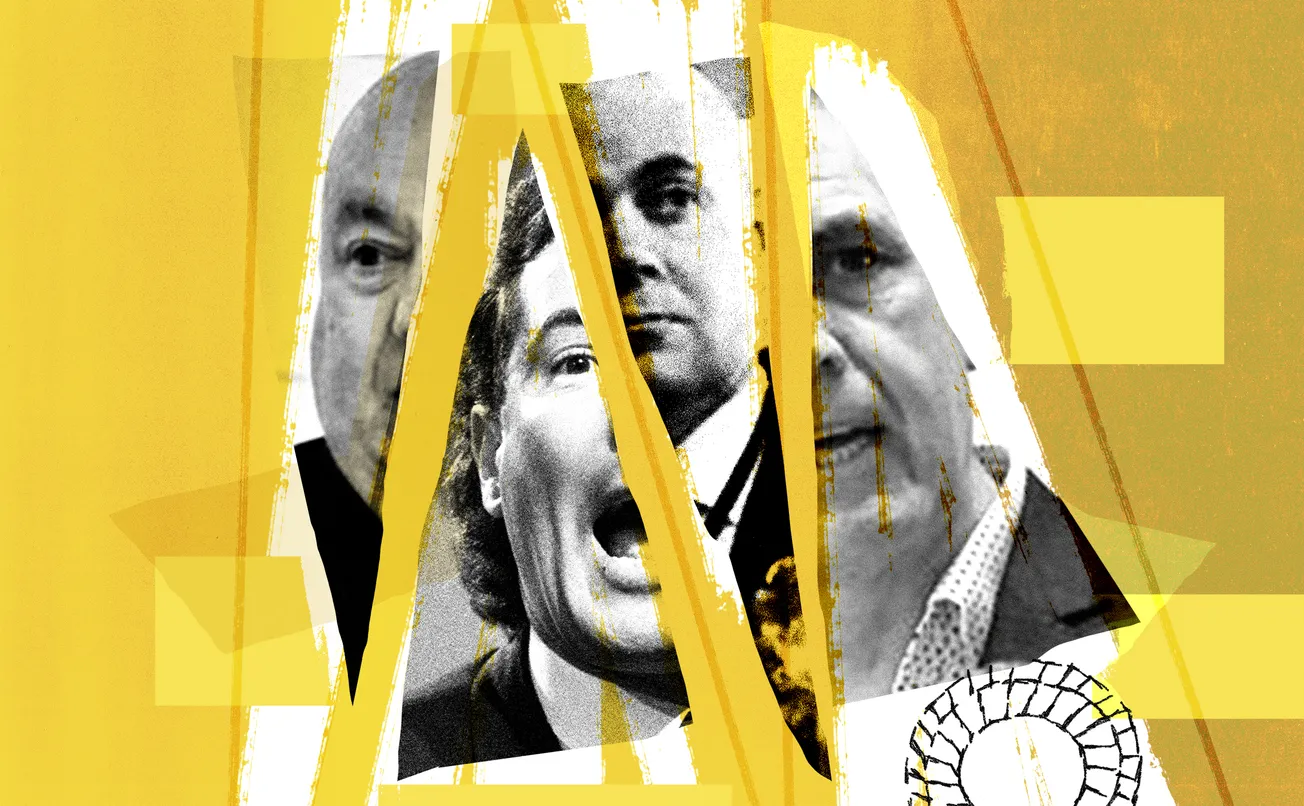

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

After years of populist fireworks a new type of leader has emerged in the city. Polite, unassuming, passionate about ironing...

We hope you enjoy today's story on Liverpool’s lack of charismatic leaders. While you're here, why not sign up to our free mailing list? You'll get access to some of our award-winning investigations, cultural reads and analysis of the issues that matter most to Merseyside.

The kids are calling it “rizz”. Some describe it as personal magnetism; the French dub it a certain je ne sais quoi. Politicians covet it; voters crave it; Jeff Goldblum exudes it. Pundits, professors, and journalists fall over themselves trying to capture its strange, terrible beauty in the flailing butterfly nets of language. It’s an elusive, sometimes ephemeral trait – not quite style, attractiveness, nor personality. And yet, it’s something most people can immediately spot: charisma.

You would be forgiven for thinking charisma is the lifeblood of a politician. Well, at least until you come into contact with the current crop. In Liverpool, our two most prominent politicians at the moment are council leader Liam Robinson and metro mayor Steve Rotheram. Of the former, one prominent ex-politician has this to say: “Liam’s someone who likes trains. Draw your own conclusions from that.”

The Post spoke to Robinson when he took over Liverpool Council in late 2022. When we asked him what really motivates him in life, his answer was “public service” (in a separate interview at the time with the Echo he was willing to open up a little more, describing a passion for ironing). But the argument in favour of figures like Robinson is that rather than craving the limelight, they simply get on with the job at hand. Most would agree the city is in a much better place now than when he came in. Before him, of course, was mayor Joe Anderson, whose much more recognisable form toppled and fell when he was arrested as part of a corruption probe in 2020. Like a jilted lover, we then rebounded to the very opposite of who held our attention hostage – the quiet, less inspiring bureaucrats whom we elected just to clean up the mess.

We see this effect at a national level too. Not so long ago, the soul of the nation seemed torn between the bombast of Boris Johnson and the sincerity of Jeremy Corbyn; then, the far less conspicuous Sir Keir Starmer swept in, apparently the political drama’s unassuming Fortinbras. But now the populist Nigel Farage’s Reform lead in the polls, Grey Labour’s days in the sun may already be numbered.

If you Google “charisma” and “Liverpool politicians”, you won’t have to scroll far to find Bessie Braddock, a bullish campaigner for the city’s poor and MP from 1945 to 1970. Known for her fiery personality, Braddock utilised everything from two-foot megaphones to firing air rifles in the House of Commons to get her points across. Deploying these flamboyant attributes and tactics to advocate for her working-class constituents is why there’s a statue of her in Lime Street Station.

After “Battling Bessie”, as colleagues and opponents dubbed her, not many fit the firebrand label — Derek Hatton, definitely; Joe Anderson, maybe. Sure, Liverpool has produced a plethora of cabinet and shadow ministers for both major parties – John McDonnell, Andy Burnham and Dan Carden for Labour; Edwina Curry, Nadine Dorries, Esther McVey, and Thérèse Coffey for the Tories. But which of these could be said to immediately command the attention of the mob with visual uniqueness, rhetorical panache, or force of personality?

Nonetheless, our current set of city leaders are notable for their beigeness or anti-rizz. It’s almost part of the brand. Previously the chair of Merseyrail, Liam Robinson was elected leader of Liverpool Council three years ago. The Post spoke to several figures across the political scene who describe him in glowing terms: “decent”; “modest”; “clever”; “a nice guy” with an “aura of quiet competence” and “self-evident integrity and honesty”; someone who is doing “a fine job in [difficult] circumstances”. The impression given repeatedly is of a committed and respectable public servant. But is he a leader?

A former colleague of Robinson’s, who now works for another council in the North West, recalls an icebreaker ideas session shortly after his election as city leader. Going around the room, everyone was asked to give an interesting or unusual fact about themselves. Some opted for what football team they controversially supported, or a wacky party trick they had hidden up their sleeves. When it came to Robinson, he bashfully announced his favourite band: Oasis.

Jon Egan, an experienced policy and communication strategist, implies that Robinson’s rise is an indirect consequence of how the previous era ended. “Those who were conspiring to anoint a new leader, they looked at Liam and thought, ‘well, he's not going to offend anybody, is he?’”

Many will ask, if Robinson is competent, honest, and gets on with the job with integrity, does any of this “charisma” stuff matter? Yes, actually — at least according to Egan. “As a city leader, you need to be recognisable,” he says. “You need to have a voice that can be heard above the tumult.” And although Robinson may be considerate and intelligent, “does anybody outside of Liverpool know who he is?”

Perhaps a more recognisable figure, then, at a national level, is Steve Rotheram. Sporting shoulder-length salt-and-pepper hair and a billowy open-top shirt, the mayor of the Liverpool City Region could almost pass as a Byronic hero, albeit played by an aged sixth-form band leader. Although he doesn’t always cut the most comfortable figure in front of cameras, he doesn’t shy away from them, either.

But few The Post speak to think he has “the gift”. When it comes to advocating for the city, he’s certainly not as confrontational as some of his predecessors. Some draw unfavourable comparisons with Joe Anderson, especially when it comes to challenging the government on policies that would negatively impact Liverpudlians. “I'm absolutely certain that Joe [Anderson] would have stood up against [the government’s welfare bill] and said ‘there's no way you should be doing this to my city,’” one local MP tells us.

Another unfavourable and repeated comparison was with Rotheram’s Manchester counterpart, Andy Burnham. The Old Roan-born mayor of Greater Manchester may not be the first politician who comes to mind when the subject of populist appeal is raised – after all, he was one of the centrist candidates who failed to stop Jeremy Corbyn’s coronation as Labour leader. But there is a perception that Burnham has grown as a politician over the last ten years and can be relied upon as a canny and, when necessary, confrontational advocate for Manchester’s interests. He was even popularly crowned “King of the North” during the COVID-19 pandemic for campaigning to secure more money for communities above the Watford Gap.

“I think Steve is in Andy’s shadow,” one former councillor in Liverpool says. “Where Andy is, Steve will follow. Andy has a proper vision, and he’s got that charisma. He shows leadership. He'll say things even when it's uncomfortable for people to hear it, or [for those] in government to hear it.”

Vision, then, is a big part of the overall charisma package. And here, Rotheram seemingly suffers in comparison. One political advisor in the North West tells us about a recent drinks reception attended by policymakers and business representatives, held at the Hilton Hotel in Liverpool.

In that meeting, top figures from across the region were given a chance to speak about their plans for economic development. Those representing Manchester pushed the narrative around the city pulling in blue-chip companies, naming a long list of science firms, law firms and opportunities created by their universities.

In recent years, the Liverpool City Region has also been trying to capitalise on science and innovation; press releases issued by the Combined Authority often highlight work at Liverpool’s Knowledge Quarter or big investments from global tech giants. Was mayor Rotheram about to share his world leading vision with the audience? Not quite. “Steve's big idea to revitalise the local economy was to do an Abba Voyage,” — a virtual concert by the Swedish pop group — “but for The Beatles,” the advisor tells us.

The problem with this, as strategist Jon Egan explains, is that Liverpool has long struggled to be taken seriously as a national power. “We've already got a massive problem of disadvantage when it comes to recognition as an important and valued place,” he says. For much of the country, our reputation is one of a “branch of the entertainment industry”. Fighting this perception is an important and difficult task — one that Rotheram doesn’t quite seem to take seriously.

“There's a huge upside to being a politician who can embody a nation or a city,” says Professor Michael Kenny, former lecturer in politics and Director of the Bennett Institute for Public Policy at the University of Cambridge. But there’s also a downside: when things are going badly, the politician becomes the symbolic Fisher King of a decaying state. “The risk is that when people feel that times have changed and that, actually, things are not going so well in a place, it's very easy for that to spill over into a sense of frustration and the desire to move on from that kind of leadership.”

That same embodiment of a city’s fortunes all too swiftly becomes redolent of decadence and perceived corruption. Innocent until proven guilty, both Derek Hatton and Joe Anderson were arrested under Operation Aloft five years ago. The following year, the Caller Report deeply criticised the way planning, highways, regeneration and property management had been handled in Liverpool, painting a picture one public policy academic called “[almost] apocalyptic”. That might explain why personalities in the city’s post-apocalyptic political landscape have only with trepidation put their heads above the parapet.

Because he keeps coming up, The Post also reached out to former city mayor Joe Anderson. Although he is due to stand trial next year for offences including bribery and misconduct in a public office, he was more than happy to give his opinion.

“I think there’s been a charisma bypass,” he says when asked about the current political scene. “Raising the profile of the city – that's your job. It's about promoting your city. That’s what mayors are supposed to do. They’re supposed to be ambassadors for the city.”

Anderson admits that the reticence of politicians to seize the limelight might well be a consequence of the Caller Report, but he says it’s like a “pause button” has been placed on Liverpool. You never hear from, or about, the people who are meant to be running the show. “To be fair to them, that’s because they don’t have a great deal to shout about.”

When asked to comment on which individuals he has in mind, Anderson is also obliging.

“[Liam Robinson] is a bit of a geek – a transport geek,” Anderson continues. “And I say that with respect.” He says some people are built to be leaders. “Some are born to be second, or part of a team.”

As for the metro mayor…“Steve turns up at tragedies, but that’s the only time we see him. Or when he’s getting led by Andy [Burnham] to announce something we’re already getting.” Anderson adds that when Rotheram was elected “he was going to have a lean, green fighting machine, but the reality is very little has been delivered.” The much-discussed tidal barrage project in the Mersey Estuary, and the lack of movement over vaunted new bus fleets, are two examples our interviewees brought up.

The mayor’s office chose not to respond to our enquiries for comment. Meanwhile, council leader Liam Robinson says that since becoming leader, his focus has been on “resetting relationships and rebuilding trust with our residents, businesses, stakeholders and the government,” stressing hard work, transparency and delivering “meaningful improvement” over “fireworks”. He’s also keen to highlight “transformational regeneration projects” such as Central Docks and Pall Mall, as well as building 10,000 new homes over the next decade across north Liverpool. “Our priorities — to improve how people live, work and travel to and around the city — are clear,” he continued. “I’m fully aware of the scale of the job at hand. We won’t always get it right, but where we don’t we are mature enough to acknowledge it and put things right.”

To many readers, Anderson’s vituperative comments might be nothing but post-facto bitterness. But they may remind others of a more combative style of local politics. If the ability to symbolise a region through sheer force of personality is, as Professor Kenny cautions, a double-edged sword… well, that is still a sword. Which is not to say that charisma is synonymous with – or necessary for – political belligerence. The late Norman Tebbit may have looked like a cross between a broom handle and a bank manager, but as Thatcher’s enforcer he could be lethally effective. Just as charisma is impossible to fully define or scientifically measure, its efficacy can depend on time, place, and the prevalent atmosphere.

With political winds at every altitude changing so quickly, whether Liverpool is about to have a populist moment is impossible to say. What’s hard to dispute is that people in Liverpool feel aggrieved: whether it’s about pensions, welfare, immigration, political indolence or foreign policy. If nothing else, the Southport riots last year showed that a trickle of discontent can rapidly turn into an explosion of rage. These barely-subterranean springs of resentment could fertilise ground for a new, anti-establishment brand of politics, for good or ill. But if that moment does come, who would have the charisma to seize it?

Thanks for reading today’s edition — we hope you enjoyed reading it as much as we did pulling it together. Don’t forget: our introductory offer is now open! Sign up for a Post subscription today and get your first three months for just £4 a month (less than £1 a week!).

Comments

Latest

Northern Powerhouse Rail is back on track. We think...

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still plays every Saturday

Does Liverpool have a ketamine problem?

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

After years of populist fireworks a new type of leader has emerged in the city. Polite, unassuming, passionate about ironing...