The lost mothers and babies of Prospect House

'I remember a lot of heartbreak and tears as their babies were taken away'

Little is known about Prospect House, a now-demolished home for mothers and babies on the Wirral. Nothing about the facility has ever been published in the media, despite it playing host to decades of traumatic separations between women and their newborn children. A few months ago, The Post’s Mollie Simpson came across a group of people who are searching for their long-lost families. Today, in an extraordinary weekend read, she tells their stories.

When I first talk to Michelle, she tells me that keeping secrets makes things feel more shameful. “We need to keep talking openly about it so we don’t forget,” she says.

I find Michelle through a private Facebook group named ‘Mothers and adopted children of Prospect House, Hoylake, Wirral’. It was formed to connect and help those who lived in Prospect House, an elegant row of terraced houses in Hoylake that served as an unwed mothers and babies home from the late 1940s until the 1970s. Many mothers are still looking for the children they were forced to give up in Hoylake. And then there are the babies, some of whom have found their mothers and lost families, while some are still looking.

Michelle helped create the group after her mother-in-law, Joan, (not her real name), confided she was forced to give up her baby daughter, Jayne, in 1961, when she was just 19. Since then, Michelle has been searching for Jayne and posting on forums and in groups in the hopes that one day, if Jayne still has her birth certificate, and she searches for Hoylake or Clatterbridge Hospital, she might find her. “Jayne’s still a part of the family, as such,” Michelle says. “If she wants to find us, she can.”

Prospect House was built in 1897 by a wealthy widow named Mrs Esther Dayer Harrington. In 1905, it became a nursery to look after the young children of working mothers, organised by a group of charitable ladies. As it became more popular, the nursery offered training courses in nursing, cooking and housework to help the mothers gain employment.

After the Second World War, British society saw a return to traditional domestic values and an emphasis on the role of the housewife. The historian Valerie Andrews writes that the unmarried pregnant woman represented a threat to this moral system. “Society marginalised both mother and child legally and socially,” she writes. In 1946, a trustee named Sir Joseph Crosland Graham began negotiations with Cheshire County Council to use Prospect House as a hostel for “unsupported” mothers. The purchase was completed by the council and in 1947, the home opened to 12 mothers and eight babies from the Cheshire area, along with three resident staff. The girls were mostly sent from the East Cheshire area, but no one from the Wirral or Liverpool was allowed to go in case someone recognised them. The odds of seeing someone you knew in a small community on the Wirral coastline, cut off from the rest of Cheshire, were minimal.

It became a place where girls were sent by their families, doctors or priests to hide their pregnancy and give birth in secret. They would work long days, cleaning, cooking and earning their keep. The one thing that Joan always remembered vividly was the cruelty. She told Michelle of being called dirty, being told that she was naughty, and days spent washing up pans and pots, scrubbing floors. Towards the end of their pregnancies, the girls would line up on the groins, a kind of sea wall meant to stabilise the beach. They would climb on the walls and wait. Then, they would be told by the matron to jump in, in case the shock of cold might make their waters break.

Joan never wanted to give up her baby, Michelle tells me. She didn’t grow up around religious concern about pregnancy and marriage, but she did grow up with a single mother and a father who’d abandoned them when she was very young. “No one can ever know about this,” was what Joan’s mother told her. They gave her herbal tea and even tried to push her down the stairs once, but the pregnancy stuck, and she was sent to Prospect House before she started showing. They told friends and family she was going on holiday, and they never spoke of it again.

She had a traumatic birth and wasn’t given any painkillers. The baby was breech — lying feet first instead of head first and she tore when Jayne was finally delivered. “You wonder when they did things like that, how many survived?” Michelle says.

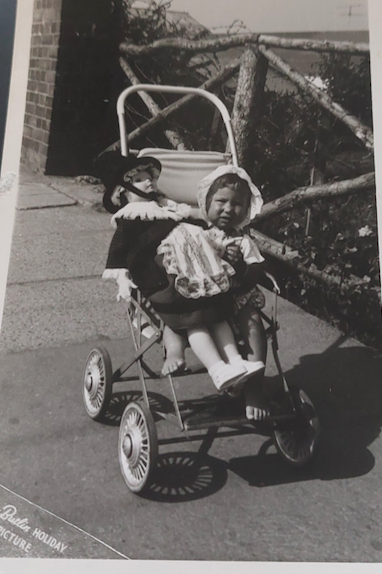

The mothers looked after their babies for six weeks. Michelle says this part of their life in Prospect House was characterised by pride and love. They’d suffered, but they’d finally got something out of it. They would breastfeed and take their babies in prams for walks down the promenade on Hoylake Beach. But there was never any choice — they knew when the six weeks were up, they wouldn’t be able to keep them.

When Jayne was adopted, Joan left Prospect House. She was told to forget it ever happened, like it was a bad dream. But she held on to the birth certificate. One day, her sister realised she’d kept it and threw it in the fire. “Jayne’s gone now, that’s it,” she told her.

“I know times were different,” Michelle says. “But I daren’t broach it with her [Joan’s sister]. It was just that reaction I think, the stress at home, the shame brought on the family.”

Michelle managed to get another copy of Jayne’s birth certificate and gave it to Joan the year before she passed away. When Michelle and Ian were clearing out Joan’s house after she died, they found it kept pristine in a little shoebox.

Two years after Prospect House, Joan got pregnant again. This time, she was stubborn. “No, I’m keeping it,” she told her family. She had fallen in love suitably this time and she insisted she would get married. Later that year, her son Ian was born. Michelle says she was never that maternal with Ian — it was rare to get a cuddle. But she had a weakness for girls and when Ian married Michelle and had two daughters, Joan formed a close bond with them.

By the 1970s, Prospect House was remodelled to provide “therapeutic holidays for mothers at risk” and was used for teenage girls in council care. A mother who lived there during that time, who doesn’t want to tell me her name, said she and her three month old baby were placed in Prospect House after a brief period of homelessness in the ‘70s. “I spent all my teenage years in care homes and institutions,” she says, “Prospect House was not the worst”.

She was just 17 years old. She was given her own room in Prospect House with a cot for her baby and remembers it being tidy and safe. The majority of the girls there were pregnant out of wedlock. “I tended to keep to myself,” she says. “I remember a lot of heartbreak and tears as their babies were taken away.” Some were allowed to keep theirs if they promised to get married and their parents agreed. She stayed for nine months and eventually, she got a council flat in Ellesmere Port just before her daughter’s first birthday. Admission rates continued to fall, and by 1977, the hostel closed. In 1999, permission was granted to knock the buildings down to make new apartments.

‘It breaks my heart’

When I ring Jan, she’s sat among letters from her biological mother, Eileen, birth certificates and adoption forms. “God, where do I start?” she says. I’m sitting in a coffee shop on the Wirral and watch the rain run down the windows until the coastline has all but disappeared. And she begins to tell me her story.

Jan grew up in Ellesmere Port, the middle daughter of Sylvia Hindle. Her dad died when she was two and a half. She has two sisters — the older one is also adopted and her younger sister was an unexpected miracle birth.

Jan is now 59 and has light blonde hair. She has always tanned very well when she steps into the sun. At school, other kids would tease her and say she looked different to her family, who were pale in complexion. “I always knew something wasn’t right,” she says. Then, when she was 10, her nan sat her down and told her she was adopted. Her biological mother was very young and unmarried, and had to give her up. “It screwed my head up for a few years,” she admits. “Who am I? Where am I from? I just wanted to know my roots.”

When she was 18, she started looking for her biological mum. Social services gave her the address of a family home in Stockport. It was 1980, and she turned up at the door alone. An old man in the garden next door looked at her and said “You’re one of the family, aren’t you.” She was startled but said yes, I am.

The family had moved just up the road, and he drove her to meet them. When her biological auntie opened the door, she knew who she was as well. It was her auntie who told her that the version of events she’d learned from her nan wasn’t quite right. In fact, her mother had her in an unwed mothers and babies home in Hoylake when she was 32 years old, and as she had severe learning difficulties, it was accepted she might not be able to look after a child.

Jan first met her biological mother Eileen in her flat in Stockport. Jan remembers the feeling of shock, of expecting a younger woman and encountering someone older and much more sensitive, much more frail than she expected. She hadn’t grown up around disability and felt an initial tug of awkwardness at first. But they sat and had a cup of tea and Jan remembers Eileen being emotional and deeply invested in Jan’s life. She told Jan her birth name was Diane, her father was a man named George, who she had a relationship with. He was in the Navy and originated from Liverpool. On Eileen’s wall was a calendar with a date marked off reading ‘Diane’s birthday’. “It breaks my heart,” she says, and we stop there for a moment.

Around the same time, Jan also found her two brothers. She has an older half-brother who grew up with learning difficulties similar to Eileen. He would visit Jan, who was living in Ellesmere Port with her son Steven at the time, and tell her he dreamed of being a pilot. “He was a funny lad,” Jan says warmly. Her younger brother, incidentally, grew up 10 minutes away from Jan’s childhood home. He was deeply private and shy, but adventurous and kind, and had travelled the world. It was thought they shared the same father. They never knew each other growing up, and felt a mixture of serendipity and frustration in the way they found each other.

“That really annoyed me in a way,” Jan says. “It just shows me they [social services] just willy-nilly gave out kids, anywhere, not thinking of the consequences of what could happen. We could have gone to the same school. We could have liked each other. We could have gone on a date. Anything could have happened.”

Jan and her brothers had a close and easy relationship. But her relationship with Eileen became delicate after that first meeting. Eileen began visiting every other day, taking two buses from Stockport to Manchester, and Manchester to Ellesmere Port, and Jan became unable to explain to her son, Steven, who was three-and-a-half at the time, who she was. “How could you tell a three, four year old that you’re adopted and his nanny isn’t his real nanny?” She says. “They just wouldn’t understand, would they?”

So one day, Jan crafted a beautiful letter to Eileen saying she needed some space. They took a break. Two years later, Jan wrote another letter saying she still needed some time, but it was lovely that they’d met, and she’d see her again someday.

‘To have something that’s your own, it’s so special’

Sifting through her documents, Jan feels lucky she found out the truth and that she had a warm and loving relationship with her two mothers, who have both now died. “She was just beautiful,” she says, talking about her mum Sylvia. “I got pregnant at 17 and I expected her to throw me out because of all the good she’s done for me and brought me up and I landed that on her doorstep. But she didn’t. She was the opposite.”

She describes the birth of her son Steven as one of the happiest moments of her life. “When you’re adopted and you have nothing, to have something that’s your own, it’s so special,” she says. She now has four children and lives with her partner.

Jan’s story is both moving and complex, and we frequently run into misunderstandings where I’m not sure if she’s talking about her adopted mother Sylvia or her biological mum Eileen. She has the capacity to find the humorous and bizarre in her story now. “God, it’s hard having two mums!” she says.

Some missing pieces remain. Jan still doesn’t know who her biological father George was. And because it could sometimes be difficult to communicate with Eileen, she never knew what her life was like when she was at Prospect House, or fully grasped the impact it had on her.

There hasn’t been much research into disabled mothers and forced adoption, but the disability historian Iain Hutchinson says: “If illegitimacy was a reason to persuade a mother to give up her baby, it follows that a mother with learning difficulties could have faced the same pressures — or would she even have been asked?” He also says there was a pernicious orthodoxy that disabled people shouldn’t marry or have kids in case they brought more disabled people into the world.

Eileen’s parents died when she was very young, and she was mostly raised by her siblings, who Jan has got to know over the years. Someday soon, Jan is going to meet her cousins.

Social services’ background information on Eileen is scant. It says she had red hair, pale skin and light brown eyes. She was a patient in Calderstones Hospital between 1954-59. In 1960, she was at Prospect House. Jan suspects the date is wrong, because her older brother was born much earlier and Jan was born in 1962. In 1964, Eileen was working in a school in Cheadle Hulme when she got pregnant again. Before the birth of her third child, she was described as “not being able to look after herself in the community and concern was raised over her ability to raise a child”.

More documents show that Eileen had Jan baptised into the Church of England, and consented to her being immunised against diphtheria, whooping cough, tetanus, TB, smallpox and polio. And then, on 28th September 1962, she went home with the Hindles.

It would take a while for the adoption process to go through. Social services expressed concern that Jan might grow up with learning difficulties and advised the Hindles just to foster her at first. “You don’t go for a baby and then give it back because something’s wrong,” Sylvia Hindle told them. “I want the adoption to go through.” “I always thought that was beautiful,” Jan tells me. The adoption went through when she was two years old.

On a Wednesday in July 1963, Eileen and Jan saw each other again. Sylvia Hindle “very readily agreed” to a visit and they sat in the office at Cheshire County Council Children’s Department. The report writes:

Mrs Hindle brought the baby in, beautifully dressed, and very brown. Miss Bardsley was pleased with her, but she was a bit tearful in the midst of strangers. She is making good progress in all ways, saying some words, imitating grown-up actions, nearly walking.

In November 1963, Eileen wrote a letter to social services to ask for an update. “I am writing to you about Diane,” Eileen writes. “I wonder if there is any word of adoption. I really don’t want to get rid of her but I would like if she had a second name. I hope she is keeping well.” She wrote letters every day for a year.

Last year, Jan walked along Trinity Road and down to the beach with her dogs. It was very sunny and felt something like a dream. “I wanted to walk the ground my biological mother did, and all sorts of thoughts went into my head,” she says. “Did she push me in a pram on a beach? Questions you will never have answered, but you know.”

Walking down Trinity Road, it’s striking how modern and quiet it feels. I’d lost track of the day speaking to Jan and Michelle and the sky was already streaked with pink when I got to the beach. The beach is empty and feels like an outsider’s view of a world that’s long gone. But you can imagine swimming in the sea, feeling the first signs of movement, the sense of longing and impossibility, the shame that never quite left.

To get in touch, email mollie@livpost.co.uk

Comments

Latest

‘Cutthroats and sell outs’: An editor’s note about Laurence Westgaph’s threats

Ian Byrne: Why the country — not just Liverpool — needs the Hillsborough Law

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

The Mersey’s clean-up cost £8 billion. So why is it still so dirty?

The lost mothers and babies of Prospect House

'I remember a lot of heartbreak and tears as their babies were taken away'