The Liverpool 'false memory' movement casting doubt on sexual assault victims

And one man's search for the truth

Pat Mills stepped off the pavement, away from the sunlit street, and into the grand but dimly lit hall.

He scanned the London venue, where he was surprised to see signs of wealth everywhere. A lot of people, he recalls, were wearing Dunn & Co. clothing, a brand middle class professionals wore at the time (it was the early 90s): tweed jackets, cavalry twill trousers, brown brogues. He heard a cacophony of southern accents; he even spotted an aristocrat. Mills felt a rising sense of discomfort.

“I felt like an intruder,” he says. “The atmosphere was very cultish, and very Hitchcock.”

Mills had set off from his home in Colchester that morning expecting to meet people from an organisation that existed to investigate and understand the experience of adults who recovered memories of being sexually abused in childhood.

“In fact,” Mills says, “it was a safeguarding organisation for parents accused by their own children or other relatives of sexual abuse.”

False memory wars

Therapists, lawyers and researchers have been arguing about how our brains store traumatic events since Freud conceived his theory of repression over a century ago.

One side of the debate — although made by a smaller and, now, largely discredited group of people — is that memories of child sexual abuse remembered by the victim in adulthood can be unreliable, if not forcibly planted by therapists. Individuals and organisations peddling such theories have directly implicated how professionals approach these crimes, and, in turn, whether survivors seek justice.

Survivors often don’t report sexual assault to police for a fear of not being believed. A decade before he became prime minister, Keir Starmer acknowledged as much when he was head of the Crown Prosecution Service, during which time he worked to reform how victims are treated by the criminal justice system.

The concept of ‘false memory syndrome’ first emerged in the US in the early 1990s, where the False Memory Syndrome Foundation (FMSF) posited that memories of childhood sexual abuse are concocted by mental health professionals who manipulate their patients using various techniques, including hypnosis and “truth drugs”. The name, with its use of “syndrome", meant to imply a scientific diagnosis, even though it’s never been recognised by any professional associations as a legitimate mental health disorder.

The FMSF formed when a group of families and professionals from in and around Philadelphia area joined together “because they saw a need for an organization that could document and study the problem of families that were being shattered when adult children suddenly claimed to have recovered repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse,” according to the FMSF website.

While Mills’ own memories of childhood sexual abuse first emerged during therapy, he had no idea about the movement trying to discredit the therapeutic process that first put him on the path toward healing.

Mills grew up on an Ipswich council estate, where he lived with his mum, a devout Irish Catholic widow. After attending St Joseph’s, a private school run by monks, he grew up, got married, and had children — all in relatively blissful ignorance. What Mills does remember about the time in his life before he recovered his memories of abuse is a “mysterious and unexplained” hatred toward the Catholic church in which he’d been raised.

In the early 1990s, when he was in his 40s, Mills got divorced, and he decided therapy was a good way to help him emotionally navigate the experience. During the process, he began to struggle with difficult feelings: “All these things that were unrelated to the relationship breakup were coming up and I was thinking, ‘My god, what is this stuff?’” he remembers.

When conventional therapy didn’t help him determine where his growing discomfort was coming from, he decided to see a hypnotherapist.

“Not the new-age ‘feel the healing golden light’ crap, but a simple ‘relax’ approach,” Mills clarifies.

He walked through a local shopping precinct, past the beautician’s next door, and sat down opposite the therapist. He did relax, at first, but then his mind went to a “dark place”. and suddenly, memories of one of his abusers started to come up, images so fast he could barely keep up with them.

Mills’ first reaction was disbelief at what the “sweet and kind” priest was doing. But then he started screaming. His memories were organised enough for him to understand that he’d been a victim of an organised Catholic paedophile ring (which, Mills says, was a relatively new concept at the time, in 1993) from when he was five or six years old.

More screaming, and eventually, the hypnotherapist gently suggested that he do something about this. But, Mills says, she was very careful not to lead him in any particular direction.

“Therapists were under attack by the false memory people in the 90s, so they were all very careful what they said,” he says.

Around the same time, the false memory movement was growing, largely thanks to American psychologist Elizabeth Loftus.

Since the 1970s, Loftus has produced a huge body of research examining the fallibility of memory. In her most famous study, the “lost in the mall” experiment, participants were told four stories about their childhood, all supposedly provided by family members. The participants didn't know that one of these stories was false, and 25% reported being able to remember the false event. The study has since been widely criticised, however, for being a) very small, and b) nothing to do with child sexual abuse, to which it became frequently applied anyway.

But Loftus’ research quickly elevated her to expert status. She has been called to act as expert witness in hundreds of US cases on behalf of defendants, including Bill Cosby. Loftus also testified on behalf of Harvey Weinstein at his 2020 rape trial, for which she presented research to back up the theory that survivors’ memories could have been distorted by negative press coverage of Weinstein. In a recent interview with the New Yorker, she described memory as “a living thing that changes shape, expands, shrinks, and expands again”.

The idea that any innocent person could unexpectedly be accused of abuse based on a false memory was quickly and widely propagated by reputable media outlets in the US and, soon enough, in the UK, too. Therapists became increasingly aware that they may be accused of implanting memories in their clients. Throughout the 90s, there were a barrage of articles and TV and radio segments attacking the credibility of survivors and their therapists.

Right before the false memory movement really started picking up steam, Ellen Bass and Laura Davis published The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse in 1988, which quickly became a bestseller in the US and across Europe.

The authors were sued several times – unsuccessfully — for allegedly inducing false memories in their readers. Co-author Ellen Bass tells me over email that, while the FMSF closed in 2019 (the foundation states the need for its existence “diminished dramatically over the years”), some people affiliated with the group still control her book’s Wikipedia page, whom Bass calls “pit bulls”. They focus almost entirely on the controversy around the book, like the authors’ lack of qualifications (Bass is a poet, creative writing teacher and counsellor for survivors of childhood sexual abuse; Davis is an author and incest survivor) and for its role in isolating and separating family members.

In an addendum in the third edition published in 1994, Bass and her co-author liken being told you’re lying about being sexually abused with being ‘under siege’, and ‘as if the abuse were happening all over again’.

Mills, while freshly processing his trauma, saw a lot of these newspaper stories about the apparent rise in false memories of childhood sexual assault.

“I was reading articles about how therapists can lead you on, that, effectively if you had memories coming up in midlife there was a very good chance they were false,” he says.

Around the same time as Mill’s memories came back to him, a close family friend started having flashbacks of their own, pertaining to being sexually abused as a child.

“She was very distressed, and asking me, ‘Do you think these memories are real?’ I told her it probably happened, and I can still see the relief on her face today that she was believed,” Mills says.

Later that day, he relayed this news to a friend of a friend, who casually told him the woman’s recollection was probably a false memory, and that he’d recently read an article about it. Mills was horrified.

Mills didn’t know who to go to about his own recovered memories, or who would believe him – and this latest reaction certainly didn’t help. So he did what anyone living in the southeast of England did in the early 1990s when they wanted to research something: he went to Charing Cross Road and hit up the bookshops.

Mills wandered in and out of the royal blue doorways of Watkins and Blackwells, and looked up every book he could find on recovered repressed memory, which is when he found The Courage to Heal.

FACT versus fiction

Around the time that the FMSF became prominent in the US, the UK was having its own revolt against survivors of sexual assault.

As far back as the 1970s, allegations of child sexual abuse in children’s homes in North Wales fuelled numerous major investigations and inquiries. This spread to Liverpool in the 1990s, and Merseyside and Cheshire police became some of the first UK police forces to investigate alleged historical sex abuse in former children’s homes and residential schools with the launch of Operation Care.

When I connect with Peter Garsden on Zoom, he’s wearing a casual shirt and sitting in a small converted office in his garage, blurry awards on the walls behind him. Not exactly what you’d expect for a man accused of making millions off the back of defending sexual assault survivors.

But while Garsden looks every inch the small-town solicitor, his humble 2D appearance belies a career spent at the epicentre of the battle of memory.

In the early 1990s, Garsden was an unassuming solicitor specialising in personal injury, working from a small high street practice in Cheadle, Stockport, when he picked up the office phone one day in 1994. It was a former client calling. This person had been a victim of sexual abuse at Greystone Heath children’s home in Warrington, and he told Garsden the police had just advised him to seek legal advice. Survivors were starting to tell their stories to the police, and an investigation was underway.

Garsden knew there was strength in numbers. He contacted the Legal Aid Agency, which provides criminal and civil legal aid to those who are eligible, including his client, to ask who was in charge of the group of survivors. No one was in charge, it transpired, and the agency suggested Garsden take up the position. So he did. He gathered all the solicitors involved in a hotel in Chester to talk strategy.

There were initially 13 survivors, but this group eventually grew to 120 across five care homes as the investigation went on, for abuse that dated back to the late 1960s. The senior barrister Garsden was working with at the time suggested he set up a public enquiry.

“The only way to do this is to raise awareness through the media and get the government’s attention, and this was the beginning of what became the nationwide child abuse scandals we know now,” Garsden says.

“I became a champion of victims of abuse from care. It was a very challenging time of my life, and a very difficult thing to do.”

Meanwhile, the police investigation was quickly spreading across to Merseyside and greater Manchester, incurring fury and disbelief from the public as it grew. In Merseyside, the police investigated 510 former care workers suspected of child abuse, and 67 were charged, resulting in 36 convictions.

“They’d tried to complain many times to the police and social workers, but they were ignored,” Garsden says of his clients.

These survivors had spent much of their lives being cast aside or disbelieved — and now that they were beginning to see justice, they were accused of lying. “Abuse witch-hunt traps innocent in a net of lies”, one Guardian headline read, while a Panorama episode in 2000 asked if some of these men were falsely accused.

Pockets of protest in and around Liverpool sprouted up, started by families of the accused, until an organised movement formed called Supporting Victims of Unfounded Allegations of Abuse, which became known as FACT.

The police investigation lost steam in the early 2000s, Garsden says, with concerns around how much resources the police was devoting to historical crimes. These were the ashes from which FACT rose — and its members really, really didn’t like Garsden.

“FACT has caused me a considerable amount of grief over the years, but I’m proud I’ve been its bête noire; it means I’m doing my job properly,” he says.

In 2000, FACT held its first meeting in St Helens, and printed its first newsletter, FACTion, a year later, which often mentioned, and were sent directly to, Garsden.

“I became an enemy of FACT,” he says. “I was frequently libelled in their newsletters for my outrageous behaviour acting on behalf of lying victims from the care system who had the ignominy to be claiming compensation from the poor, innocent individuals trying to look after them.”

Garsden pauses to make sure I’ve grasped his sarcasm.

Garsden didn’t get his public enquiry; instead, in 2002, a Home Affairs Committee launched one of their own, examining the police’s ‘trawling’ for evidence of abuse in care homes, rather than waiting for complainants to come to them.

Garsden presented to the committee 13 ways in which he thought the criminal justice system could be improved. But, in what became the “most unpleasant” two hours of his life, he felt like he’d become one of the enquiry’s targets.

The committee’s report concluded that police 'trawling' created a ‘new genre of miscarriages of justice’. The police, in response, stopped actively going looking for evidence, Garsden says, until the Jimmy Savile case in 2012.

“This was the damage FACT intentionally did to the criminal justice system,” he says.

Brian Hudson, FACT’s secretary, sees things very differently, he tells me over Zoom from his home office. It’s the middle of the day, but when he sees how dark the room looks on camera, he switches the light on.

Hudson tells me that the police in Liverpool were “doing the opposite of normal policing”, and that making accusations against care home workers was a “lucrative business”.

“We’re not saying they were all lying – we know some people were abused as kids and we abhor all kinds of child abuse,” he says. “We were against people being caught up in a big net.”

FACT goes under the radar, Hudson says, because when they advise someone accused of childhood sexual abuse and the person get acquitted, there’s no further action, so they don’t make headlines. But over the years, FACT’s website, which he says has around 6,000 visits per month, has been a first port of call for many people accused of sexual abuse, which is “devastating” for them, Hudson says.

“You can’t understand it unless it’s happened to you,” he says. “From that day forward, you’ll never be able to function properly again.”

FACT has two helplines, one that connects the caller directly with Hudson.

“A lot of people tell me I’ve saved their life,” he says.

The first thing he advises callers to do is to find a solicitor because, according to Hudson, the odds are stacked against them and they start on the back foot. (In fact, only around five percent of those accused of sexual assault are even charged.)

FACT was preceded in its work by the British False Memory Association (BFMS), which was recently forced to close its doors. The BFMS was founded in 1993, and FACT followed six years later.

BFMS was founded by Roger Scotford, who was accused of sexually abusing two of his three daughters, to support parents whose children were accusing them of sexual abuse after recovering the memories in adulthood. This vested interest wasn’t uncommon among BFMS board members, several of whom have been investigated over sexual harassment, or convicted of sexual offences.

BFMS existed, much like FACT, to advise accused parents. In 2021, the BFMS boasted that it had helped to discontinue 26 cases of sexual abuse over the previous six years. After its closure (due, the organisation says, to lack of funding) one of its previous members, Kevin Felstead, who was the frontman of BFMS until its demise, jumped ship to join FACT’s board of directors.

“I try to help people, but I’m not superman,” says Felstead.

After mentioning that he’s been practising martial arts for 50 years, Felstead tells me he developed an interest in false memory when his sister, Carole, died aged 41, after accusing her parents of sexually abusing her. He became convinced that therapists could implant false memories in their clients.

The BFMS had financial difficulties for the last decade of its life. According to Felstead, that’s because it’s not the kind of subject that lends itself easily to funding. Presumably, the organisation has also lost some of the credibility and influence it enjoyed in decades past, now that the debate around the reliability of recovered memories has become much more nuanced in recent years. We now know that our brains can hide traumatic memories from our conscious mind.

After a few short-lived resurrections when old members died and left money to the charity in their wills, BFMS closed in January this year. But the organisation lives on, albeit in a diminished way, in FACT, with members including Felstead having crossed over.

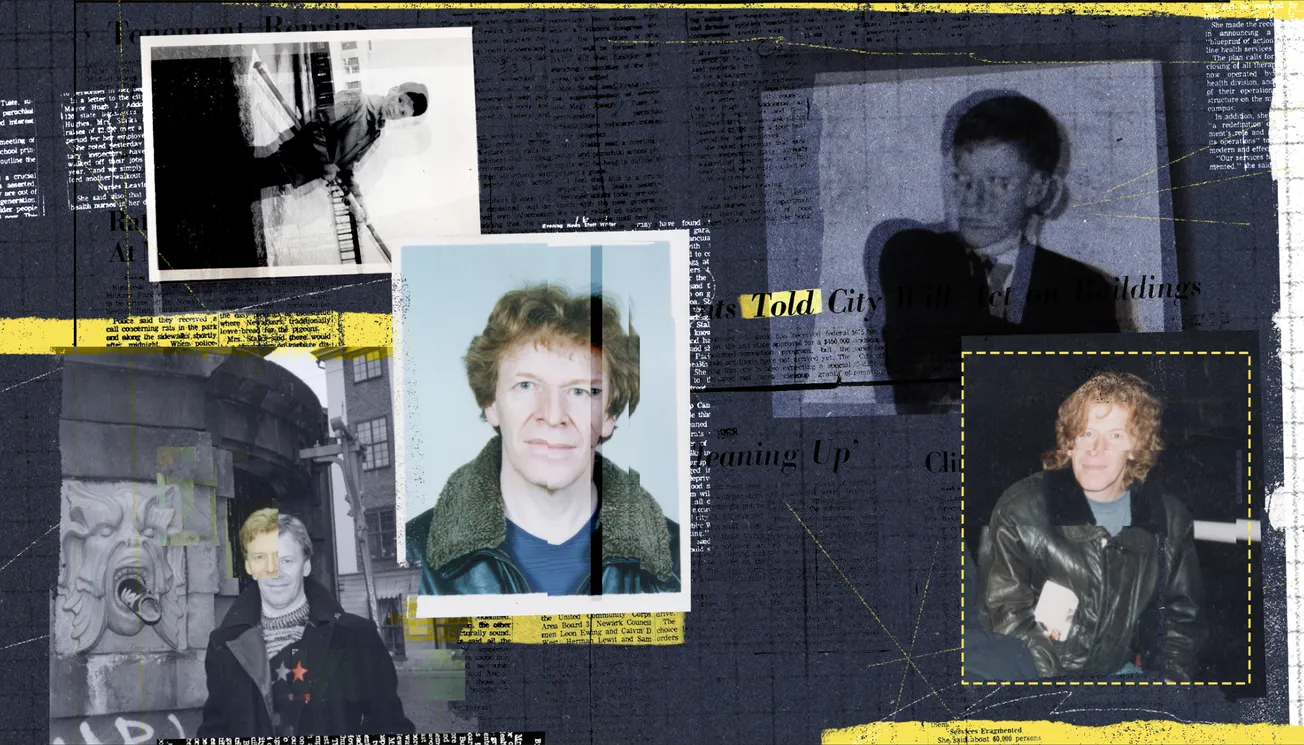

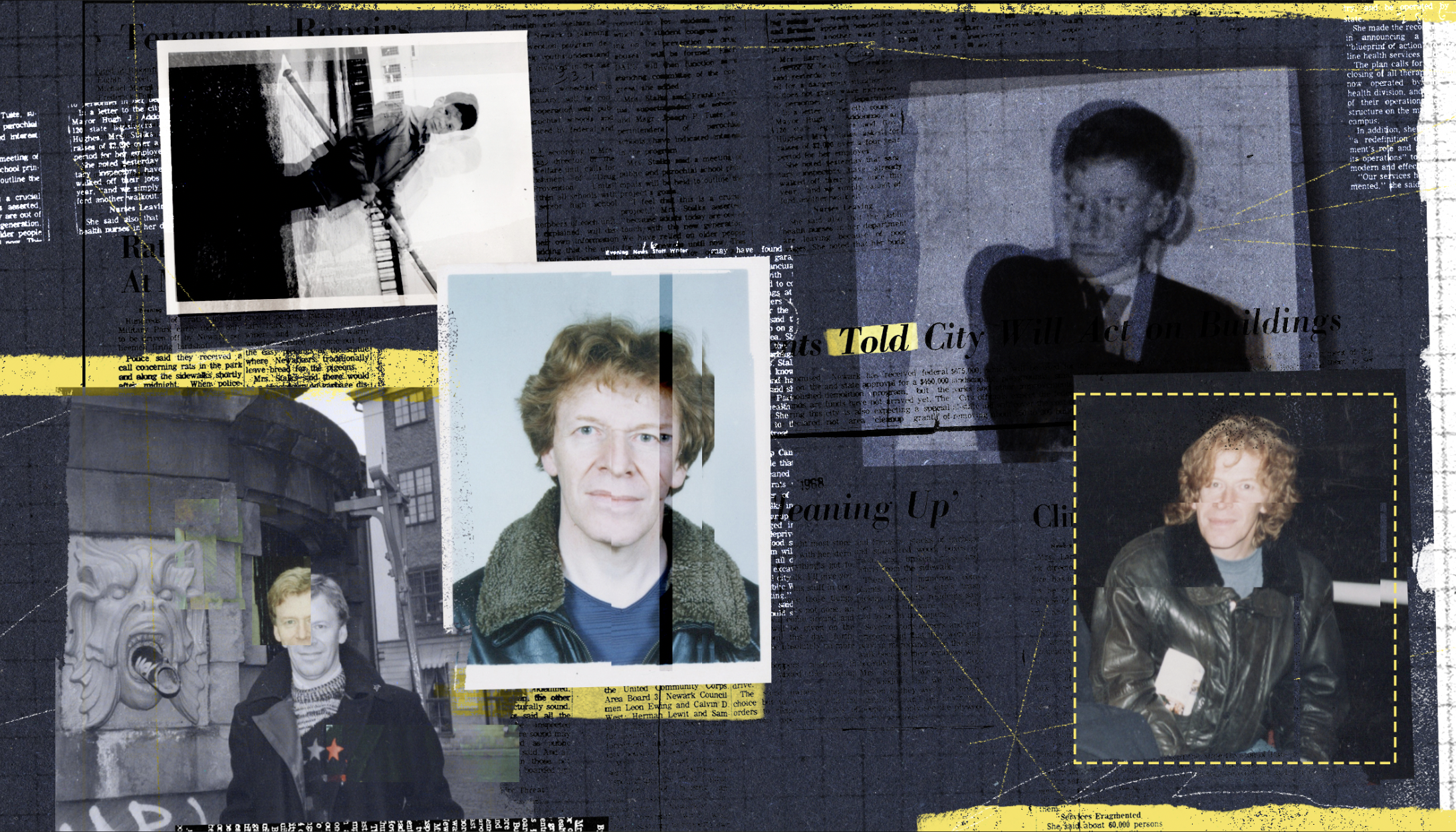

Pat Mills stumbled upon BFMS during his research attempts to understand what was going on with him; he wanted to perhaps meet others who’d gone through something similar. This is when he first inadvertently infiltrated BFMS’s annual conference in London.

Mills was hoping to connect with other survivors, who, like him, had recovered memories later in life. He was open-minded, and assumed that the organisation’s mission was in earnest. Above all else, he just wanted to understand more about memory.

He sat down in the audience, and saw that the panel of speakers for the afternoon included Elizabeth Loftus, who was there to promote her latest book and give a lecture about Freud.

A doctor sitting behind Mills angrily complained about the risk posed to his reputation of a BFMS letter sent to him without being marked as confidential, which his secretary then opened.

A voice at the back of the lecture theatre, someone connected to BFMS, attempted to lift the mood in the room, announcing the rising number of ‘recanters’ – survivors who claimed they were abused, then recanted and apologised.

At some point, an audience member mentioned The Courage To Heal, which incited “veritable hiss of hate” from the rest of the crowd, Mills recalls.

“The strongest feeling I took away from that day was that no one showed any compassion for their children, whether the accusations were real or imagined,” he says.

The second, and last, members’ meeting Mills infiltrated was at the home of BFMS founder Roger Scotford — another 'very wealthy occasion' according to Mills. It was a sort of meet-and-greet, Mills recalls. He wanted to understand where the group was coming from, and whether any of their claims were legitimate. “I was trying to believe in false memory syndrome or evidence of a halfway point, at least,” he says, “but I was progressively finding there isn’t one.”

He noticed one man who was crying. “He seemed to be the only one not from the middle class,” he remembered. “I naively thought that, if he’s in tears about all this, maybe it’s real.”

The false memory movement’s legacy

Mounting research has discredited the idea of falsely implanted memories. Brain imaging studies have identified neurological mechanisms involved in recalling repressed sexual abuse later in life, and psychologists argue that it’s much more common for people to seek therapy once these memories have already started coming back to them, or to recover them spontaneously and independently during therapy.

The CPS recognises that there is no robust evidence proving that therapy produces false memories. Nonetheless, the concept of false memories is still used by some defendants accused of sexual abuse in court.

“In my experience, false memories of sexual abuse, implanted by therapists, are incredibly rare in this country,” says Richard Scorer, head of abuse law at law firm Slater and Gordon. “There’s no evidence to my knowledge of this happening in any significant way.”

“In 30 years of working on thousands of child abuse cases, I can count on the fingers on one hand the number of cases where there was a suggestion of any kind that the complainant had ‘recovered’ memories of sex abuse.”

He recalls a campaigner on false memory telling him that hundreds or thousands of people have been wrongly accused and convicted based on false memories implanted by therapists, and that it will all one day come to light.

Needless to say, that hasn’t happened. Though they’ve failed to bring about any large-scale reckoning, the BFMS and FACT have involved themselves in the criminal justice system, and proponents of false memory have acted as expert witnesses in court cases. It’s unclear how often this happens, however, as Scorer says data isn’t collected to show how often witnesses are used for false memory defences.

Though it’s difficult to determine FACT’s influence on ongoing court cases, they were instrumental in discouraging police from proactively investigating historical abuse cases in the 90s and early 2000s. Police constable Terry Grange, the lead for complex child abuse investigations at the time of the 2002 inquiry into police trawling, was also in charge of an internal handbook on the investigation of historic institutional child sex abuse. Garsden remembers seeing at the top of this handbook an instruction telling the police not to 'trawl'.

Garsden had gone to Grange to “plead with him” not to ban trawling, arguing that it’s important police are proactive when looking for evidence of child sexual offences, since evidence from many years ago is often so difficult to find. Also, it's important that there are witnesses to support a claimant, Garsden says. "When the burden of proof is beyond reasonable doubt, as it is for the police, corroboration is very important, otherwise it is one person's word against the other and that is rarely enough.”

A review later concluded that police failings hugely contributed to the Rochdale scandal, in which a network of men sexually abused girls as young as 13. It was in the wake of this scandal that Starmer, head of the CPS at the time, instructed the police to do an about-turn on how they approached crimes of historical sexual abuse.

Hudson resents that the pendulum has swung back after the 2002 inquiry, and that legal professionals as well as the broader culture are now more sympathetic to survivors. Or, as he puts it, the police “have to believe every story, no matter how fantastic it is”.

False memory still affects civil cases, Garsden says. The law states that victims of child sexual assault must issue legal proceedings by the age of 21, but the average age of Garsden’s clients are between 35 and 50. There is a loophole that allows cases outside of this time limit, but only when it can be shown to be a fair trial. This is often determined by the judge’s conclusion of how good the claimant’s memory is, Garsden says.

“As the success of a case fought so many years after the abuse took place depends, in most cases, on the memory of the victim, the subject of memory is exposed to allegations of vagueness, mistaken belief, errors, and outside influences,” he says.

This, Garsden adds, opens the door to memory ‘experts’ instructed by the abuser’s representatives, who then attack the credibility of the victim.

Revenge of the survivors

Mills, while he tells himself he’s recovered from his abuse, sometimes suspects that he’s “bullshitting” himself. One of his abusers was his English teacher in school, which was a particular betrayal for Mills, who’d always wanted to be a writer.

“I was known on my council estate as ‘reader’, because I always had a bunch of books under my arm,” he says. “But from the age of 16 to 18 I didn’t read a book. I tried, but my eyes would glaze over.”

“The false memory movement has affected victims very badly indeed,” Garsden says. “It makes them very angry, when their memory is questioned. They’ve been largely disbelieved all their lives.”

Sadly, there have been backlashes against survivors of sexual assault over the last century and half that extend far beyond Freud, Bass writes in the third addition addendum to The Power to Heal.

Why are some people so convinced by the debunked concept of false memory syndrome? Because, she writes, “denying the reality of child sexual abuse appeals to a basic human need: the need to distance ourselves from human cruelty.”

After the False Memory Syndrome Foundation was disbanded in late 2019, Rape Crisis South London published a blog post celebrating its demise. “This foundation has caused untold grief, confusion and self-doubt for survivors coming to terms with remembering abuse that was perpetrated against them in childhood,” the post read. “[False memory syndrome] became mainstream with shocking speed, especially compared to the issue of male violence against women, which feminists had been speaking about for decades before it ever came into mass consciousness.

“Survivors doubt themselves enough due to abusers’ grooming, manipulation and lies, and it seems to us that FMS merely worked to enhance those perpetrator tactics,” the post went on. “It cast doubt on survivors’ credibility in a world where abuse is already ignored or denied, and created yet another context wherein abusers can get away with their crimes.”

Mills is now a successful comic book writer. One of his most famous characters, Judge Dredd, is “a composite bogeyman of all my recollections of fear of my teachers”, he writes on his website. He tells me nearly all his stories — especially those he wrote in the 80s — are “thinly disguised attacks” on the Catholic church, such as Nemesis the Warlock and the evil Torquemada, who was a Catholic Priest.

A Doctor Who story Mills wrote in the 1980s was recently televised; starring David Tennant, the episode follows the Star Beast, the Meep, a creature of white, purest innocence — but “it’s actually a vile creature of unspeakable evil,” he says.

Despite the hours we talk on the phone, Mills relays some of his account to me over email, where his retellings are much more vivid. He prefaces each written account by clarifying that he wrote them as one, long flow of memory, unedited; he hadn’t even read them back to himself. I came to see these defensive preambles as a glimmer of insight into the trauma caused by the memory wars, a self-consciousness about the reliability of his own memory, which were just as revealing as the accounts themselves.

Mills decided to find a new therapist six years ago, on the cusp of turning 70.

“I thought, if I describe to an English therapist what went on in the Catholic church in my childhood, they’d think I was crazy, but if I described it to an Irish therapist, they’ll get it,” he says. At the appointment, he mentioned that he knew one of his abusers was still alive because he’d spoken to the local paper.

The therapist then told Mills that, because she lives in Ireland, she had a mandatory duty to report what Mills told her to the police.

Going to the police hadn’t crossed Mills’s mind, not least because this abuser was by then 89 years old. But alongside his therapist, he sent a written account to Ipswich police.

“The police called me, and the next thing I know he’s been arrested,” Mills says. “He turned up to the police station with a coterie of supporters who claimed he wasn’t well enough to be formally charged.”

And this is where it all ends, Mills says — and it was “a very satisfactory ending, because he’d been called to account. The police took on my testimony alone, which is encouragement for other people going through something similar.”

While FACT is still in operation, the BFMS UK and FMSF in the US have died out due to the changing tides in the decades since Mills’ memories came back to him. The MeToo movement has helped raise public awareness of the importance of listening to survivors, while the UK’s criminal justice system now understands the value in being proactive when it comes to unearthing child sexual abuse.

Mills lives in Spain now, where he writes, engages with his fans online, and keeps a blog about his and others survivors’ accounts of alleged sexual abuse perpetrated by the Catholic church.

Mills recently hired a private detective, who found out the exact spot one of his abusers had been buried. He wanted to go to the cemetery in Ipswich and etch ‘child abuser’ across his grave; but he decided, in the end, that he didn’t need to: “Because I have the power,” he says.

There’s another reason Mills doesn't feel the need to deface his abuser’s grave —he recently recovered a memory of being believed as a child. Just once.

He remembers joining the Cub Scouts, and being so excited. But he stopped after only one week. He has a blurry vision of telling his mother’s boyfriend about experiencing abuse, which is why he didn’t want to go back.

“He believed me,” Mills says. “The first and only Catholic to believe me. The others were too scared or brainwashed. But this man was a labourer from Dublin and I believe he drank the Irish version of Buckfast tonic wine. That’s stronger than the Scottish Bucky, with its lethal reputation.

“I like to think he beat the living shit out of [the abuser], but I doubt it. Probably harsh words to the priest. And that was it. But maybe after a bottle or two of Bucky, who knows? I can hope. I can dream.”

Comments

Latest

From Jimmy McGovern to Len McCluskey: The household names rallying behind Writing On The Wall’s employees

The lost department stores of Liverpool

Last minute drama, local revamps and Liverpool Doc Club

From Simone's to Belzan: How a hospitality magnate seduced Liverpool's tastemakers

The Liverpool 'false memory' movement casting doubt on sexual assault victims

And one man's search for the truth