The enduring mystery of an infamous gig in Widnes

The rave revolution that wasn't televised

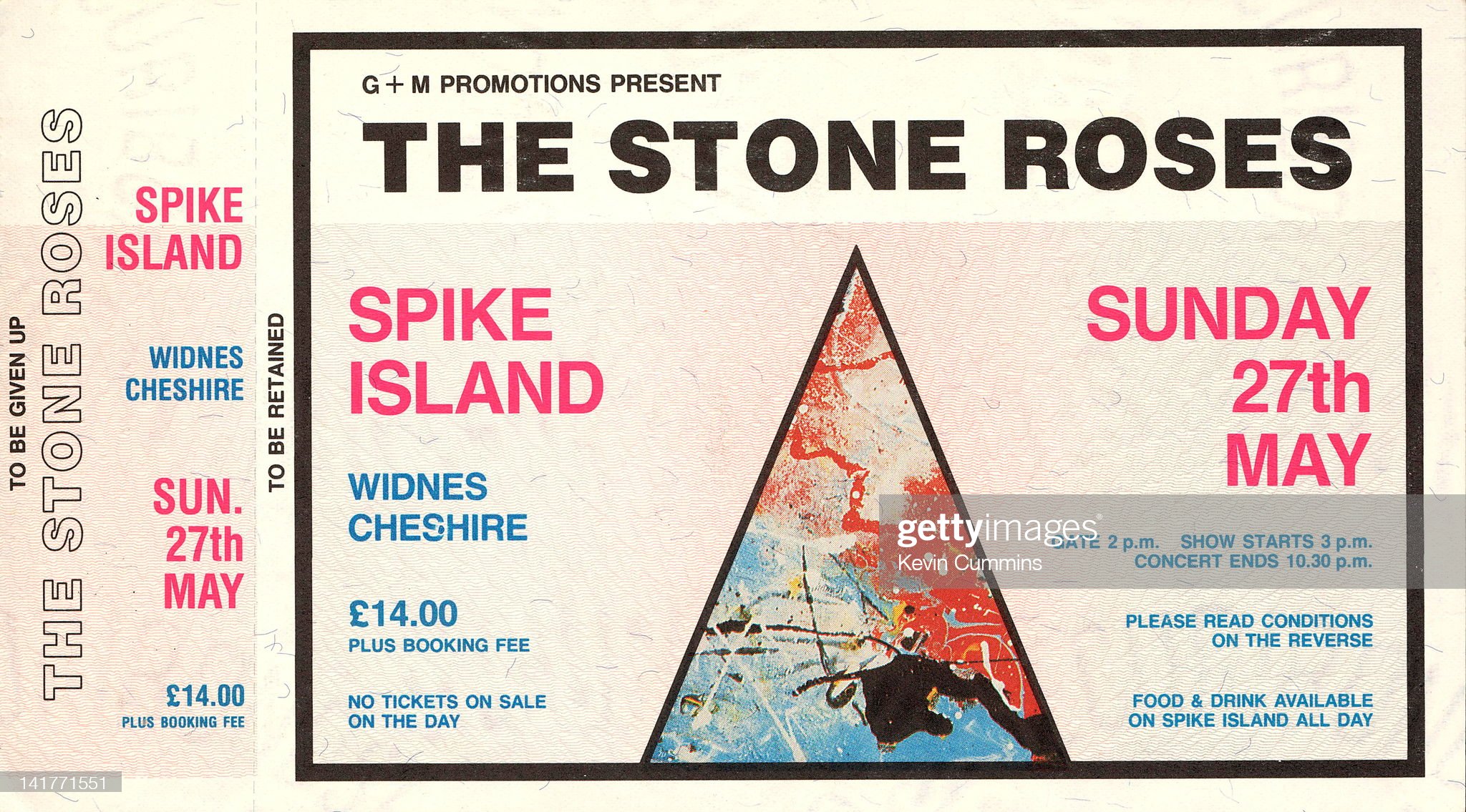

Weeks before the Stone Roses and Haçienda DJs set foot on Spike Island on 27th May 1990, the show was already being called “the most important gig in the history of the world”. Hype and hyperbole swirled around a festival organised at the height of “Madchester” mania, one which offered people a welcome weekend of escape in a country of poll tax riots, civil unrest and impending recession.

“Everything was shit in the North West then,” says Chris Coghill, the writer of Spike Island, a coming-of-age film about five teenagers desperate to make it to The Stone Roses gig. “But at the same time, it was such a fucking special time to be northern. Rave culture was a straight-up flat refusal to feel bad in the face of adversity. Spike Island was going to be a celebration of that. It was the pinnacle of it: a refusal to have a shit time.”

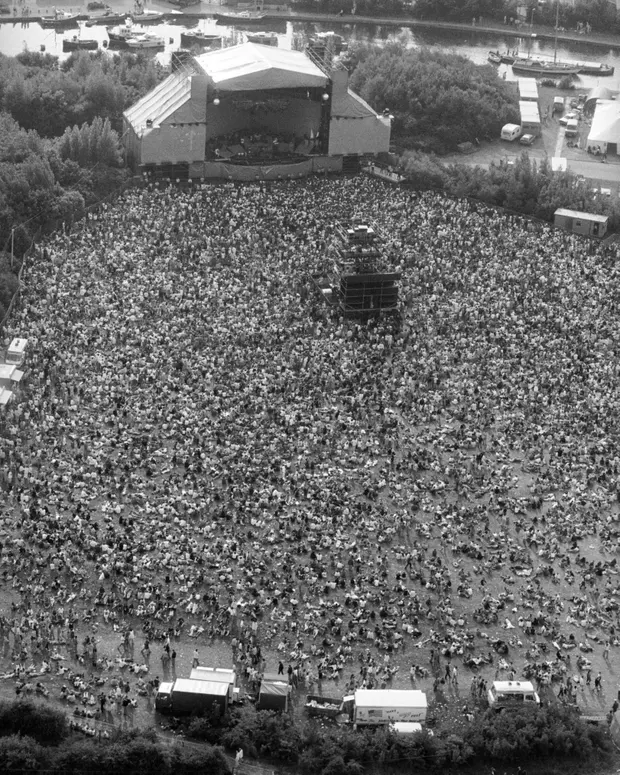

Stone Roses fans at Spike Island. Widnes, 1990.

— British Culture Archive (@britcultarchive) 2:47 PM ∙ Jan 29, 2021

Photo © Patrick Harrison.

The Stone Roses and the DJs involved were taking their sound out of sweaty clubs to allow it to blossom in fresh surroundings. They would play a behemoth outdoor gig — turning a patch of ordinary British land into hallowed turf.

A scouting mission commenced. Whilst the big arenas were ruled out, promoters knew they still needed a place that was designed to withstand an explosive reaction. So, they chose a chemical plant. A toxic waste dump in a former life, Spike Island rested on the banks of the River Mersey — having been repurposed by the local authorities into a public green space.

The access point to this peculiar isle park was the brawny working-class town of Widnes — the home of hulking grey factories, a mighty rugby league team and a mammoth through-arch bridge sporting hexagonal patterns if it were stitched together by a giant mechanical spider.

Widnes had largely abandoned the chemical industry which, while creating local work, had polluted its skies and stenched its streets. And, like so many northern regions in Thatcher’s Britain, the town seemed lost and tired, described by one of its own residents — author Stuart Turton — as the kind of place “where horrible things queue up to happen”.

So why Widnes? In many ways, this was what the rave movement was all about: reaching young communities who felt abandoned, aimless, angry and wanted an outlet. It was also a culture that was obsessed with innovating, and Spike Island would be another example of flipping the festival script, all in front of an enormous crowd.

Dave Haslam, a four-year resident DJ at the Haçienda, was booked to warm up the audience before The Stone Roses would walk on the stage. There were a few raised eyebrows when it was announced the festival would take place outdoors, and in Widnes, he remembers. “My generation weren’t outdoor festival people — our idea of a party was a basement venue with sweat pouring off the ceiling. Glastonbury hadn’t quite reinvented itself for the modern era at that point. We weren’t used to standing in a field listening to music.”

‘What is this place, Spike Island?’

But suddenly, Widnes became the place everyone needed to be. A frenetic scramble for £14 tickets ensued. “It was like a pilgrimage,” Dave says. “People came from all over. It felt like a bit of an adventure — [everyone was like] what is this place, Spike Island? It wasn’t the local park, it was out there. Part of the experience was just getting there. I’m sure there were some people who even spent the night walking home to Warrington, Chester and Liverpool.”

Not everyone made it. Around 30,000 people were there at Spike Island that day, while the rest of us have only caught a glimpse. We know that Haçienda guest DJs such as Paul Oakenfold and Frankie Bones also played on the bill, alongside a Zimbabwean drum orchestra. But other details of the afternoon are the subject of fierce debate.

One of the unlucky ones was Chris Coghill. A guy he knew promised him a ticket at the last minute, and he couldn’t get hold of him. Instead, he remembers sitting devastated for the whole afternoon. “I’ve always regretted never getting down there,” he sighs, his tone tinged with a heavy whiff of regret. “I wish I’d gone down there and tried to blag it.”

Fiona Neilson, a producer who worked on Spike Island, never made it either. “I remember feeling really left out not being able to go,” she recalls. “A few still went without tickets who tried to climb over fences and swam the river in an attempt to get in. But even then, loads of people didn’t make it inside.”

Still wracked with the feeling that he had missed out, Chris decided to channel his anxiety into a screenplay about friends who become obsessed with making it to the big gig. Spike Island began as a TV series which eventually morphed into a film funded by Chris Collins and the British Film Institute — produced by Fiona and directed by Mat Whitecross (in a magnificent twist of fate, the Stone Roses announced a shock reunion in 2011 before Spike Island wrapped).

The filmmakers shot around the island itself and convinced a farmer around the corner to open up his field for the festival scenes. But despite going one further than the curators of the film, many of the main characters in Spike Island still never quite make it to the promised land. One manages to pop his head over the top of the fence, another peeps through a panel for a split second. But that’s all they get. It’s all most of us have gotten.

Myth and notoriety

The mythology of Spike Island has thrived in part due to an infamous lack of footage, with the show only surviving in a handful of scratchy clips captured by fans on smuggled camcorders (filming equipment was on a list of prohibited items alongside cans and bottles). An official camera crew never ended up shooting — allegedly under instructions from the band and associates.

“Back then, people were less concerned about documenting things than they were about what was going to happen next,” Dave explains. “There was this attitude of not having the time to document it. It was more: Let’s crack on. If we’re gonna change the world, we better get on and do something.”

Photos of the Spike Island crowd have become collectables, and the gig is largely projected through the notoriously unreliable prism of 30-year-old memory. As such, it has become increasingly difficult to separate fact from fiction.

Some have called the event an anticlimax plagued by technical difficulties and poor sound, with not enough drink available on site. Others complained that sporadic clouds of dust puffed up from the ground and sent members of the crowd into coughing fits, whilst a few have said the headline performance from the Stone Roses — who finally arrived on stage around 9pm — was below par.

Plenty, of course, say it was a night to savour.

Mat Whitecross, director of the Spike Island film, uncovered these varying accounts during his research. “We heard it was the greatest gig of all time and that it was the worst gig of all time — a magical night and a disaster that was the first bit of damage that led to [The Stone Roses] breaking up,” he says. “I’ve been to events where people would tell me years after — ‘I can’t believe you were actually there’. Your own experience is often very different. It’s also been a very long time, now. The hallmark of a great gig is that you can’t remember it the day after, never mind 30 years later.”

In the absence of any official archive footage, the creators rented out local housing, bought baggy ‘90s threads from eBay, and shot party scenes at northern pubs. Fiona explains that it was less about a flawless replication of Spike Island and more about capturing the surge of optimism at a time of economic neglect, and the magic and tribalism of music culture looking solely towards the North for inspiration.

Dave Haslam was spinning tracks from a scaffolding setup in the crowd 50 yards from the stage alongside the sound and lighting engineers. He remembers from where he was standing the sound was quiet but the mix was good. But what was striking about Spike Island wasn’t the technicalities, but how young the crowd was: “There was a sense of a revolution. A young crowd feeling it was all theirs: their band, their music, their time. Those who went were looking for something… and being precious about the sound wasn’t top of the list.”

Spike Island has been called everything from a “shambolic mess” to “Woodstock for the Baggy generation”, its legacy repeatedly rewritten with each passing year; the picture becoming more vivid and vague at the same time. An epilogue to the film was even added as recently as 2021 — with the festival replicated using tribute acts and DJ sets for ‘Spike Island: The Resurrection’.

“Whatever happened on stage at Spike Island, it did see a lot of different people coming together,” Mat says. “And it was a turning point in lots of people’s lives.”

Aftermath

It’s true that things changed after that. As Bob Marley & The Wailers’ Redemption Song pumped through the speakers at the end of the night, filtering through the throngs of ravers waddling off the island, something started to shift.

DJs associated with the Haçienda continued to take the sounds of northern rave culture to Chicago and Boston that summer, whilst England’s glorious 1990 World Cup run produced hedonistic party scenes back home that fused sport, fashion and music. But more sinister elements also bubbled up beneath the happy-go-lucky party culture across the North, with gang trouble and gun violence breaching club doors. The Haçienda had been investigated by police at the start of the decade, and within months the club began to spiral out of control (with trailblazing label Factory Records going bankrupt in 1992).

After The Stone Roses stepped off the Spike Island stage, the band spent months embroiled in legal battles with their label — circumstances which pushed pioneers of the rave movement away from the strobe lights and below the dim bulbs of courtrooms.

Things were never quite as delirious again. Spike Island was the peak of a movement and the beginning of the end. The country was entering a new era and with it came a fresh soundtrack of Britpop and rock ‘n’ roll — a genre of head-nodding anthems fronted by swaggering, opinionated young rebels with proud regional accents and an axe to grind.

It will never be settled as to whether Spike Island was a success or not. But regardless of whether it was glorious or ghastly, it was a watershed moment. And for a flicker in time, Widnes was the place the whole world wanted to be.

Comments

Latest

‘Cutthroats and sell outs’: An editor’s note about Laurence Westgaph’s threats

Ian Byrne: Why the country — not just Liverpool — needs the Hillsborough Law

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

The Mersey’s clean-up cost £8 billion. So why is it still so dirty?

The enduring mystery of an infamous gig in Widnes

The rave revolution that wasn't televised