The definitive guide to Scouseness

Southport’s own Josh Mcloughlin studies the tribes of Merseyside

This week, we’re delighted to have partnered up with The Fence. They’ve supplied this piece — about the slippery definitions of Scouseness — from the latest edition of their brilliant magazine. If you’d like to subscribe to The Fence, do so here.

What is a Scouser? England’s other regional identities seem to have been more or less clearly defined. The Tyne, Wear and Tees rivers sort Geordies from Mackems and Smoggies. The M60 forms a neat enough perimeter around Mancunian identity (allowing for the exception of Salford). The historic dividing line between Brummie and Black Country was the coal seam north-west of Birmingham. True cockneys, everyone knows, are born within earshot of the bells of St Mary-le-Bow. Trying to define Scouseness, however, isn’t as simple as it might appear.

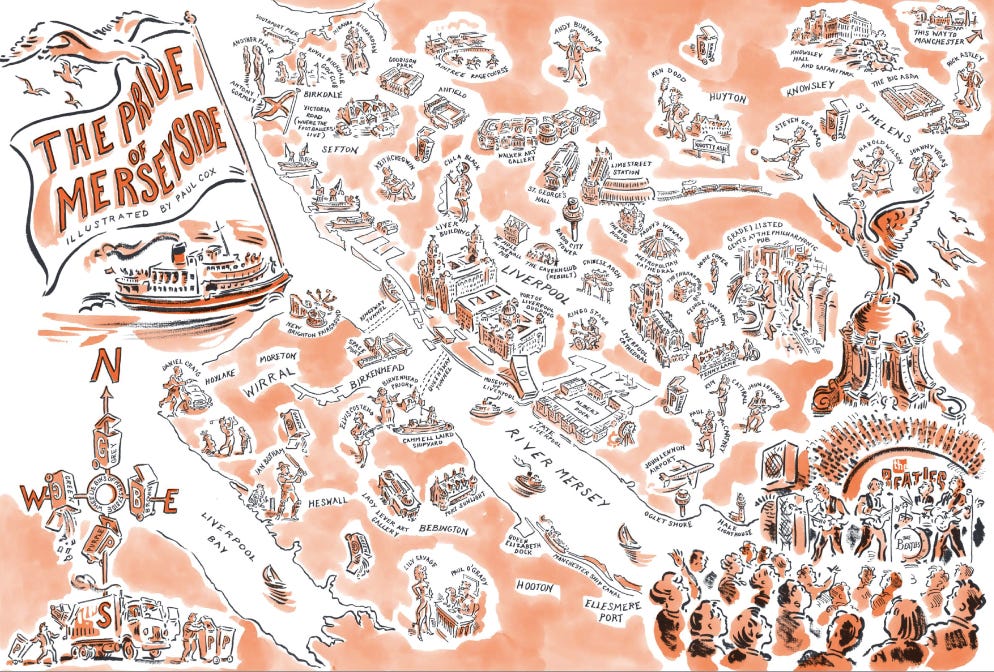

Liverpool is notorious for its exceptionalism, of course, whether self-ascribed or media-spun. The banners at Anfield proclaim ‘We’re not English, we are Scouse’, the city’s Riverside constituency is the most republican in Britain and a distinctly Liverpudlian identity is deeply and proudly felt. But dispersed across the area’s five metropolitan boroughs — the City of Liverpool, the Wirral, Knowsley, Sefton and St. Helens — are not one but four hotly contested identities (or slurs, depending on how you see yourself): Scousers, Plastic Scousers (known colloquially as Plastics, Plazzies or Placcies), Woollybacks (or simply ‘wools’) and the Posh.

In Merseyside’s tangle of tribes, birthplace is only one factor among many, dialect deceives and geography is an unreliable guide. The city and its boroughs are riven by a complex and baffling series of intra-regional cultures, rivalries, stereotypes and criteria of belonging to one (or sometimes several) of these groups. Despite the intense urban patriotism associated with the city, there is no agreement — and very often impassioned debate — about who exactly is who on Merseyside.

For some, bins hold the key to determining Scouseness. Liverpool City Council’s purple wheelie bins — intended as a mix of Liverpool red and Everton blue — have become an eccentric badge of civic pride for residents, as cherished as the Pier Head, the Albert Dock or Penny Lane.

Yet the more you try to locate true Scouse identity in a particular area, accent, attitude or economic status, it becomes clear how these supposed cultural dividing lines and their accompanying criteria become complicated and muddied to the point of opacity. Some areas that have purple bins are also unquestionably posh (Childwall, Woolton, Mossley Hill, Aigburth, Allerton, Grassendale, Cressington). Some areas that definitely feel Scouse (Huyton, Bootle, Kirkby, Seaforth, Waterloo) don’t have the borough to back it up. By the same token, some posher areas (Blundellsands, Crosby, Maghull, Thornton) seem to have secured ring-fenced Scouse status despite lacking the requisite bin or proximity to the city centre.

Locals conveniently forget that when they were introduced in 2000, many residents hated them. Some bin collectors even went on strike due to threats from members of the public. Now, though, rows about Merseyside’s identity politics will often boil down to someone drunkenly shouting ‘What colour’s your bin la!?’ in smug triumph.

But by bin logic, some of the most famous ‘Scousers’, including Jamie Carragher (Sefton, grey bin), Steven Gerrard, Stephen Graham (both from Knowsley, brown bin) and Paul O’Grady (Wirral, green bin) would be relegated on the technicality of being born outside the purple promised land.

A more inclusive and generous definition is that anyone born in the L postcode area is a Scouser. Some people on the Wirral are still bitter that the peninsula changed from an L to a ch postcode in 1999. Yet like bin colour, postcodes fail to define Scouseness. The 41 L postal districts include Hale — in Cheshire! — as well as Ormskirk, Burscough, Holmeswood, Mawdesley, Scarisbrick and Rufford, all of which are in West Lancashire and therefore a priori canonical Woollyback territory (more on that later).

Aside from the boroughs, bins and postcodes, the most obvious marker of Scouseness appears to be the accent. The historian John Belchem says a Scouser’s identity is ‘immediately established by how they speak rather than by what they say’. Alan Bennett — a typically dour Yorkshireman, and thus innately predisposed to hate Lancastrian levity — wrote in his diary in 1985: ‘Every Liverpudlian seems a comedian, fitted out with smart answers, ready with the chat and anxious to do his little verbal dance.’ ‘I have come to dislike Liverpool’, he went on, because ‘Liverpudlians [...] have a cockiness that comes from being told too often that they and their city are special. The accent doesn’t help.’

Tradition has it that Scouse is one-third Irish, one-third Welsh, one-third catarrh. The throaty, rapid-fire delivery of the local vernacular, shaped by immigration, sailors’ slang and the cosmopolitan entrepôt of the docks, has become synonymous with the city. Pete McGovern’s 1961 tune In My Liverpool Home made famous by folk group The Spinners, called it ‘an accent exceedingly rare’.

In fact, there was a campaign in the 1950s and 1960s by local linguists, historians, poets, comedians and musicians to save what was perceived to be a unique dialectal identity threatened by the contagious homogeneity of Received Pronunciation, radiating out from London on the BBc’s post-war airwaves.

Ironically, the success of that campaign — and what historians call the ‘Scouse industry’ of Liverpudlian popular culture in the mid-20th century — did not just preserve the accent but exported it. The bleed of Scouse from the city across and beyond Merseyside, not only via the city’s cultural exports but its urban expansion, means that accent is no longer a reliable badge of authentic Scouseness.

For instance, in places wholly outside Merseyside, such as Runcorn (Cheshire) and Skelmersdale (Lancashire), you’ll often hear thick Scouse accents. It’s a result of slum clearances from the inner city (particularly the Scotland Road area) to these New Towns (which also included Kirkby) in the 1960s.

Native Liverpudlians forcibly cleared out of the city passed Scouse accents onto their children and the overspill estates continue to take their cues from Liverpool rather than nearer urban centres like Wigan, Warrington or Chester.

On the Wirral, especially around Birkenhead, the local accent is often far more ‘Scouse’ than in the affluent suburbs to the south and east of the city centre, such as Aigburth, Childwall, Woolton, Allerton, Mossley Hill, Calderstones and Grassendale — all of which fall within the hallowed purple bin zone. Likewise, Bootle, Litherland and Seaforth (in Sefton) and Stockbridge Village and Kirkby (in Knowsley) cultivate some of the most intense Scouse accents you’ll hear (think Carragher and Gerrard).

But none of these contradictions prevent the accent from being jealously, zealously policed by the city’s self-appointed linguistic gatekeepers. Which brings us to our next tribe: the Plazzy. A Plastic Scouser is essentially a Merseyside mockney: someone who affects a thick Scouse accent when in fact they have none at all or a gentle lilt at most.

Anyone from the Wirral, Knowsley, Sefton or St. Helens — as well as far-flung outposts like Ellesmere Port or Chester that remain locked in the orbit of the city by the Merseyrail network — might be accused of being plastic if they ham up their accent in an attempt to fit in. To be Scouse carries a hefty cultural cachet, but to be plazzy is a cardinal sin on Merseyside: anathema to the authenticity on which the city prides itself. But plazziness is quixotic; indeed, it has its own curious plasticity.

Liverpudlians from the more affluent inner suburbs, where the vernacular is less pronounced, might amp up their accent to disguise their privilege in a city that fiercely guards its working-class mythos. But who’s more plastic: someone brought up in Allerton (purple bin, average house price £975,000) who attended the £4,800-a-term Blue Coat School and puts on a Scouse accent, or someone from Primrose Court, Huyton (brown bin), which is in the most deprived decile on the 2019 Index of Multiple Deprivation, where houses go for as little as £15,000?

‘Woollyback’ historically referred to workers from outside Liverpool (usually Lancashire or Cheshire) who came to work in the city, either as scab labour on the docks or to deliver coal from the mines to the east — wearing, according to legend, fleeces on their backs.

Today, Scousers (self-identified of course) might consider anyone without a Scouse accent a wool, whether they’re from Moreton, Manchester or Mars. Woollybacks are a Scouser’s tragic foil, the yin to Scouse yang; the demons in Liverpool’s urban cosmology and the butt of endless jokes that reinforce Scouse superiority.

The difference is not only linguistic but cultural. Scousers see themselves as urbane, witty and trendy, whereas stereotypical ‘wool behaviour’ includes an oafish penchant for rugby over football, wearing bad trainers (which for Scousers means virtually any trainers aside from Air Max 95 110s) and dancing to Mr Brightside in embarrassingly shit nightclubs.

However — and no Scouser would ever admit to this — woollybacks are central to a Liverpudlian’s sense of self. The concept of the woollyback is the very condition for the possibility of the concept of the Scouser. The Scouse-Wool binary is Jacques Derrida’s theory of the supplement translated from the seminar room to Concert Square; from philosophical abstraction to the Scouse übergrocks exchanging aggressive banter with lads up from Widnes on a Saturday night in town.

Without the woollybacks against which Liverpudlians constantly, obsessively, define themselves, Scouse identity simply would not exist.

Last of all are the ‘posh’. This unwanted moniker is usually assigned, with some justification, to the wealthier exurbs. The seaside resort of Southport in north Sefton, for example, is the only constituency on Merseyside with a Tory Mp, a choice duly punished by relentless pisstaking.

Southport is variously construed as Posh or Wool, but definitely not Scouse — some Sandgrounders still stubbornly put ‘Lancashire’ on their envelopes. The benighted borough of St. Helens, the eternal whipping boy of Merseyside, seems to offer one of the few certainties: 100 per cent Wool (according to self-professed Scousers, of course).

The difference between Plazzy and Posh is also never clear — indeed, they’re often synonymous. Formby is home to many footballers but is also full of wannabe gangsters desperate to pass as true Scousers. The east of the Wirral, just across the Mersey from the Albert Dock, feels — and, most importantly, sounds — very Scouse. The affluent west of the Wirral, especially around West Kirby, Heswall, Hoylake and Meols, might be classed as Posh, Wool and Plastic all in one. Scousers will occasionally dismiss the whole peninsula simply as ‘Welsh’.

Then there are complete oddities like the tiny rural hamlet of Oglet, near the airport. It boasts purple bins and an L postcode but nothing remotely Scouse, or remotely anything, has ever happened there. Not only that, you have to drive through Hale — still in Cheshire! — to get there. Oglet might be the strangest case of all: Scouse bins, Liverpool address, Woollyback approach, Posh countryside setting.

Some on the Wirral, however, will tell you that true Scousers originated ‘over the water’. Liverpool was only granted its letters patent by King John to become a borough in 1207. By then the monks at Birkenhead Priory, founded in 1153, had been ferrying passengers across the Mersey for a half-century.

Given all these complex and often contradictory criteria, we’re no closer to understanding what or who is a Scouser. Apart from St. Helens, the northern reaches of Sefton and the extremities of the Wirral, most areas of Merseyside might lay some sort of claim to Scousedom. All this proves is that, as an identity, being a Scouser is a chimera, a moveable feast, and largely in the eye of the beholder.

Any serious attempt to answer the question ‘What is a Scouser?’ must eventually concede that reaching a definitive conclusion is impossible. Admittedly, some areas are ‘more Scouse’ than others. Kirkdale is a million times more Scouse than Birkdale; Kirkby is far more Scouse than West Kirby.

But the truth is that Scouseness is something of a Möbius strip, or perhaps an ouroboros: a self-sustaining but ultimately self-defeating attempt to impose a strict binary on a messy, chaotic cultural continuum. On Merseyside, to be Scouse means everything — and nothing at all.

Comments

Latest

Ian Byrne: Why the country — not just Liverpool — needs the Hillsborough Law

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

The Mersey’s clean-up cost £8 billion. So why is it still so dirty?

Between Labour, Reform and Jeremy Corbyn, what does Liverpool’s electoral future look like?

The definitive guide to Scouseness

Southport’s own Josh Mcloughlin studies the tribes of Merseyside