In search of Liverpool’s lost poet

‘Cavafy’s verse is free, simple, and universal’

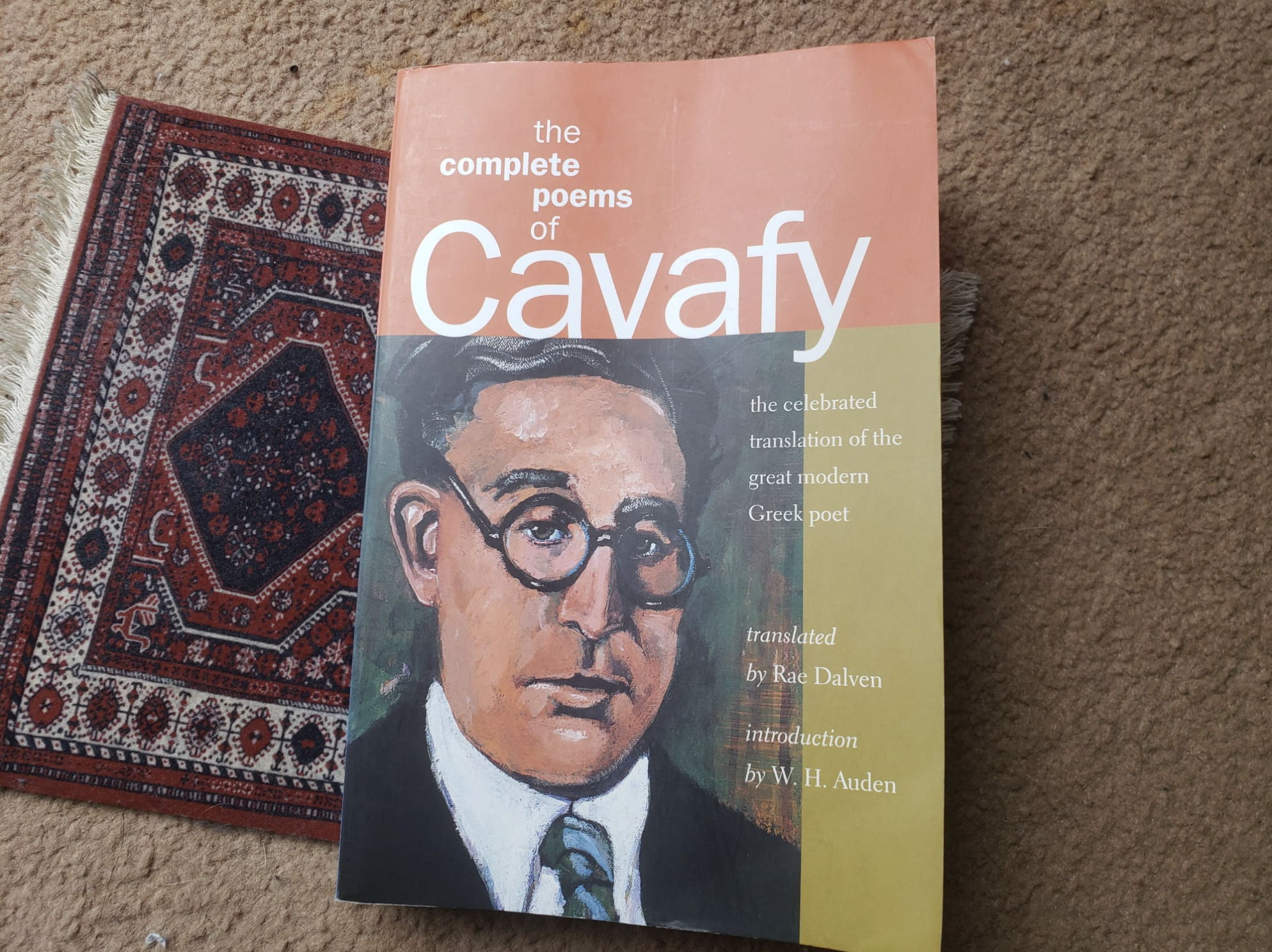

I am walking through Liverpool in search of one of the most significant poets of the modern age. The sky is grey, and intermittent showers force me to dive into the occasional pub. Tucked in my bag is a copy of the complete poems of Constantine P. Cavafy, translated by Rae Dalven. Cavafy is one of the most influential poets of the 19th and 20th centuries and, for a time, he called Liverpool home.

I stand outside the first house Cavafy lived at in Liverpool, 12 Balmoral Road, Elm Park. There doesn’t appear to be any blue plaque. A Ukrainian flag hangs limply in a window close by. I look around for any signs that the poet had once lived here: Nothing. The street Cavafy lived at in Alexandria now bears his name. I feel Cavafy would be a more interesting name than Balmoral.

The only real sources we have on Cavafy are his poems – and in these, all is open to interpretation. He destroyed most of his letters and left very few journals. The only significant biography that exists in English was written by Robert Liddell in the 1970s, and it tends to be more informative about Cavafy’s family than about the poet himself. In Cavafy’s poetry, the poet hints at the difficult task awaiting any future biographer:

Only from my most imperceptible deeds

And my most covert writings –

From these alone will they understand me.

But perhaps it isn’t worth exerting

Such care and such effort for them to know me,

Later, in the more perfect society,

Surely some other person created like me

Will appear and act freely.

“Some other person created like me.” Cavafy was gay, and this may partly explain why so much of his private correspondence was destroyed. It’s insinuated by some sources that Cavafy’s first gay experiences took place in Liverpool. We know Cavafy was born in Alexandria on the 29 April 1863. He had six brothers, all of whom would end up dying before he did. We know he worked for the Ministry of Public Works of Egypt (then controlled by the British) all of his working life, but only started “serious” work at 29: a damn good idea! We know he lived for much of his life alone, and that he was fluent in English, French, and Greek…This much we know about Cavafy, but little else.

In the recently published book, The Greek Community of Liverpool: A History 1822-2022, S.B. Williams explains how the Greek population in Liverpool exploded in the 1850s, when Greek merchants began trading cotton and grain in the city (an increasing amount of cotton came from Egypt, via Alexandria, after the end of the American Civil War). Cavafy’s father, Peter John, first moved to Liverpool as a merchant in 1852, settling in 33 Bedford Street South (in what is now the main campus of the University of Liverpool). One of Cavafy’s brothers, Aristides, was born here in 1853.

The family then moved back to Alexandria, where Cavafy was born. Peter John became one of the richest merchants in Alexandria. He died in 1870, and much of the money went with him. The family moved, Cavafy in tow, back to Liverpool, to 12 Balmoral Road. Things picked up financially for the family for a brief period, and they moved to London. Then came the financial panic of 1873, which caused a two-decade economic stagnation in Britain — and which seemed to affect merchants particularly badly. The family moved back to Liverpool, 45 Huskisson Street, before moving again, to Alexandria, this time (nearly) permanently. Cavafy’s mother, Haricleia, always called England “Home sweet home”.

Cavafy is described as the poet of Alexandria, the Mediterranean port in Egypt, founded by Alexander the Great. The other cities he lived in, London, Constantinople, Liverpool, are dismissed as insignificant by many academics who have written about him. Daniel Mendelsohn (editor at large of the New York Review of Books) stated in a lecture on Cavafy that: “he had lived in Alexandria for his entire life, with the exception of a couple of years in Constantinople.”

Incorrect. His formative years were spent in England, and mostly in Liverpool. He had British nationality for a time. His poems speak of a deep melancholy for the past; and Liverpool was a part of this. My favourite is ‘Candles’:

The days of our future stand before us

Like a row of little lighted candles –

Golden, warm, and lively little candles.

The days gone by remain behind us,

A mournful line of burnt-out candles;

The nearest ones are still smoking,

Cold candles, melted and bent.

I do not want to look at them; their form saddens me,

And it saddens me to recall their first light.

I look ahead at my lighted candles.

I do not want to turn back, lest I see and shudder –

How quickly the sombre line lengthens,

How quickly the burnt-out candles multiply.

Cavafy left Liverpool when he was 14. He likely went to school here. He spoke Greek with an English accent and spoke English with a slight Liverpudlian accent. As Liddell states in his biography: “When the Cavafys left Liverpool in September 1877 all the money the family possessed was about £300.” Cavafy’s brother, Peter, lost his job as manager of Cavafy and Co. on Fenwick Street in Liverpool and returned to Alexandria as a humble clerk. Cavafy and Co. disappeared.

Such a catastrophic fall from grace, although materially devastating, helps to nurture a poet’s soul. Can you imagine miserable old Philip Larkin the millionaire? Liverpool was where Cavafy lost his financial security. Such a place is likely to stick in one’s mind. One of Cavafy’s most famous poems is called ‘The City’:

You said, “I will go to another land, I will go to another sea.

Another city will be found, a better one than this.

Every effort of mine is a condemnation of fate;

And my heart is – like a corpse – buried.

How long will my mind remain in this wasteland.

Wherever I turn my eyes, wherever I may look

I see black ruins of my life here,

Where I spent so many years destroying and wasting.”

You will find no new lands, you will find no other seas.

The city will follow you. You will roam the same

streets. And you will age in the same neighbourhoods;

Always you will arrive in this city. Do not hope for any other –

There is no ship for you, there is no road.

As you have destroyed your life here

In this corner, you have ruined it in the entire world.

I stand outside 45 Huskisson Street, the corner of the world where the Cavafys lost their wealth. Cavafy lived here for a year. It was, and still is, a grand Georgian townhouse, but when the family moved here, they had lost nearly all their money, and it must have felt 1000 miles from their previous house in Hyde Park, London. I look in my book for a photo of Cavafy: bespectacled, with dark features, and a slightly arrogant air (the look of a man who has lost his fortune but not the haughtiness that goes with it). E.M. Forster described him as a “Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing at a slight angle to the universe.” It starts to rain, and I move on to the Greek Orthodox Church at the bottom of Princes Avenue.

In some ways, 19th-century Liverpool was more like Cavafy’s romanticised, ancient Alexandria than 19th-century Alexandria. Liverpool had a distinctly classical air – what with the neo-Grecian St George’s Hall, and the statues of 18th and 19th century statesmen, dressed like Roman senators. Liverpool also boasted a large collection of ancient Greek sculptures and pottery in its museums. (Cavafy, who favoured the return of the Elgin Marbles to Greece, was probably horrified by this. Thank God that debate has been settled...) There were, and still are, many Greek restaurants scattered across the city.

Then there is the Orthodox church of St Nicholas, built in 1870, and still open, modelled on St Theodore’s church (now a mosque) in Constantinople. Alexandria was called a city of many religions, but the same could be said of Liverpool in the 19th century – opposite St Nicholas is St Margaret’s Church, and the Synagogue. Further up is the Welsh Presbyterian church. Not far away, is one of Britain’s oldest mosques.

Alexandria, one of the most important ports of ancient times, had lost nearly all of its ancient beauty by the time Cavafy lived there. Liverpool, in Cavafy’s age, was one of the most important ports in the world, second only to London, servicing an Empire which was bigger than that of Alexander the Great.

The Greek community of Alexandria was not the same as that which lived in the city at the time of Anthony and Cleopatra; the merchant class had moved there in the 19th century. Alexandria’s beauty was contemporary, and most of that was destroyed during a British naval bombardment in the 1880s (it was around then that Cavafy moved to Constantinople for two years.)

The rain becomes too much, so I beat a retreat to a pub, the Caledonia, in the Georgian Quarter. Fortified by a pint of Guinness, sitting with a friend who has joined me, I open the book of Cavafy’s poems. There is an old man sitting at the next table. A group of musicians have entered, and are playing Irish folk songs: fiddle, guitar, tin whistle. The old man looks indifferent, with a newspaper open in front of him. And I open my book and read a poem to my friend:

In the inner room of the noisy café

An old man sits bent over a table;

A newspaper before him, no companion beside him.

And in the scorn of his miserable old age,

He meditates how little he enjoyed the years

When he had strength, the art of the world, and good looks...

He recalls impulses he curbed; and how much

joy he sacrificed. Every lost chance

now mocks his senseless prudence.

…But with so much thinking and remembering

The old man reels. And he dozes off

Bent over the table of the café.

Cavafy’s life in Alexandria was — mostly — mundane. He continued toiling away in the Ministry of Public Affairs (Cavafy described his job as ‘The Third Circle of Irrigation, i.e. the Third Circle of Hell) until 1922. He lived, in some comfort, in a seedy part of Alexandria, above a brothel, for the rest of his life. He died, like Shakespeare, on his birthday in 1933, at the age of 70. Cavafy belonged to a world that has vanished. He did not identify with any national state, rather he belonged to a mercantile class where commerce had been their passport.

As E.M. Forster said of Cavafy: “Greece for him was not territorial. It was rather the influence that has flowed… through the ages.” He didn’t like being called Greek, preferring the term Hellene, an adjective that evokes a time when Hellenic culture dominated the whole Mediterranean – he never lived in what is now modern Greece.

He wasn’t British or Scouse either – and he probably held some disdain for the British, after a naval ship shelled his family home in Alexandria. He was more a citizen of the past than the contemporary world. Much of Cavafy’s poetry is set in the ancient world, or during the days of the Byzantine empire. My favourite of his historical poems is ‘Nero’s Term’:

Nero was not alarmed when he heard

the prophecy of the Delphic Oracle.

“Let him fear the seventy-three years.”

There was still ample time to enjoy himself.

He is thirty years old. The term

The god allots to him is quite sufficient

For him to prepare for perils to come.

Now he will return to Rome slightly fatigued,

But delightfully fatigued from this journey,

Which consisted entirely of days of pleasure

at the theatres, the gardens, the athletic fields…

evenings spent in the cities of Greece…

Ah the voluptuous delight of nude bodies, above all…

These things Nero thought. And in Spain Galba

Secretly assembles and drills his army,

The old man of seventy-three.

This is a typically playful, and vaguely menacing historical poem of Cavafy, with a hint of homoeroticism thrown in. Nero, the Roman emperor, and maker of Christian candles, is delighted by the prophecy of seventy-three years. But Galba, who will become emperor himself, is the seventy-three he needs to fear (Nero killed himself as Galba approached Rome. He was 30).

In the Caledonia, this is the only historical poem I dare to read to my friend. Because of the historical settings, usually in the East, Cavafy is a bastard to read out loud. You get into the flow of things, and then are hit by a verbal wall that you clumsily tumble over. How do you pronounce: ‘Artaxerxes’, ‘Orophernes’, or ‘Lacedaemonians’? It is too much for me who, it turns out, has pronounced voluptuous wrong my whole life.

So often, it is not Alexandria or Constantinople he names, but the city. “And melancholy, I came out on the balcony – came out to change my thoughts at least by looking at a little of the city I loved, a little movement on the street, and the shops.” But this city he describes is a composite of places: Alexandria, Liverpool, London, Constantinople. A composite of different times.

I arrive at the river, without really knowing why, but it seemed as good a place as any other to end my walk.

Let me stand here. Let me also look at nature a while.

The shore of the morning sea and the cloudless

sky brilliant blue and yellow

all illuminated lovely and large.

Cavafy’s most famous poem is ‘Ithaka’, which is too long to copy in full here (but is well worth a read). Ithaka was the home of Odysseus, who spent ten years attempting to return after conquering Troy. The poem is about the pleasures of a journey, not the ultimate destination. It seems an apt poem to end with:

Ithaka gave you the beautiful journey.

Without her you would never have taken the road.

But she has nothing left to give you.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka has not defrauded you.

With the great wisdom you have gained, with so much experience,

You must surely have understood by then what Ithacas mean.

Along the river. It is the journey not the destination. I have enjoyed my time with Cavafy. He chose to live most of his life in Alexandria, and he is buried there. There is no doubt he loved the history of the city, echoes of the ancient world that inspired him so much. But Alexandria was only one part of the equation that made the man. I like to think a little of Liverpool was thrown in there as well.

Comments

Latest

‘Cutthroats and sell outs’: An editor’s note about Laurence Westgaph’s threats

Ian Byrne: Why the country — not just Liverpool — needs the Hillsborough Law

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

The Mersey’s clean-up cost £8 billion. So why is it still so dirty?

In search of Liverpool’s lost poet

‘Cavafy’s verse is free, simple, and universal’