In search of Leviathans

The story of a Liverpool whaler who explored the Arctic

In 1800, a ship called the Dundee was set to sail from Whitby Harbour. This would have been business as usual, except for one detail: a young boy had clambered onto its decks and hid himself. This wasn’t just any young boy. The ship’s captain, William Scoresby, was a farm labourer turned eminent whaler and he had stopped in Whitby to see his family. The stowaway was his son, William Scoresby junior.

The ship was bound for the icy north waters of the Arctic, and not wanting to miss the tide, Captain Scoresby gave his orders and the Dundee set sail. “Oh never mind,” he said. “He will go along with us.” When they reached the Shetland islands, he tried to return his son to dry land, but once again, 10-year-old William was triumphant, finding his way back onto the ship.

Over two decades after his first taste of whaling and the frigid Arctic, in 1822, Scoresby Jr voyaged on the Baffin, a Liverpool whaling ship that served as a research vessel. He was a devout man and a meticulous researcher — intellectually precocious as a boy, at 17, he began studying natural sciences at the University of Edinburgh. In the summers he sailed with his father on the whaling ship Resolution.

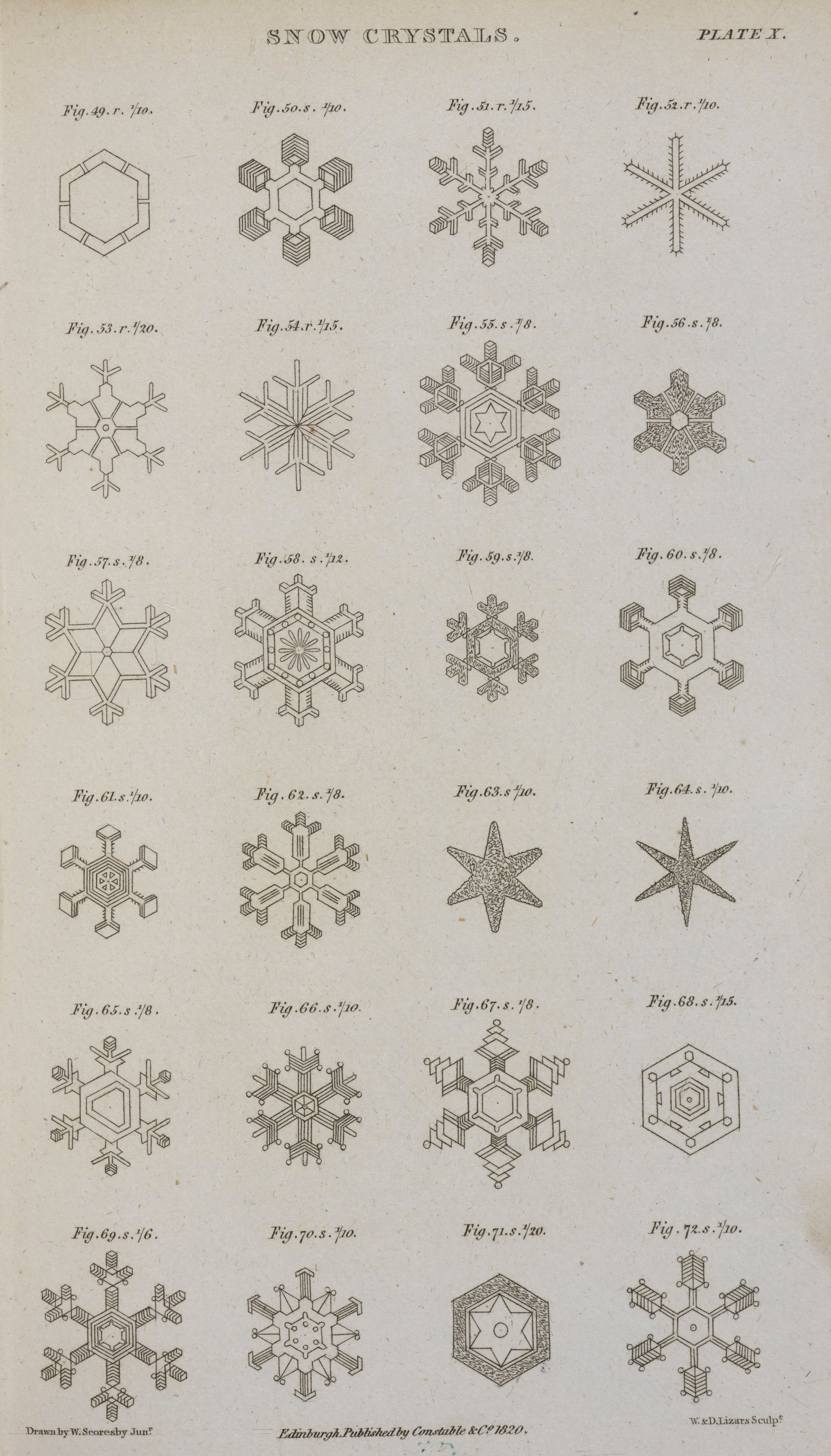

Being a successful scientist meant that he was a successful whaler — he was the first to notice that whales ate plankton (at the time they were called animalcules). Wherever plankton bloomed, there would surely be whales. During his career as a whaler, he made a plethora of detailed notes and intricate ink drawings of snow ice crystals and Arctic landscapes.

“He was just enthusiastic about everything he touched,” Dr Chris Routledge, a former academic at the University of Liverpool tells me. Now a photographer, he’s currently writing a book about William Scoresby Jr, provisionally titled Letters to Elizabeth. In 2013, Routledge organised Moby Dick on the Mersey, a festival which included a UK-first marathon reading of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (even allowing for the beauty of Melville’s prose, marathon’s the right word: it’s 135 chapters and an epilogue long).

I read Moby Dick at university, and our lecturer steadily rowed us through its pages. I was drawn by the thought of being out at sea, the familiar shoreline of home swallowed whole by sky and water. As a person of morbid persuasion, my favourite part was — of course — that ending: the thunderous, awful climax. Scoresby makes an appearance in Moby Dick as Captain Sleet, a “very boring” man (says Routledge) who writes everything down.

…it was plainly a labor of love for Captain Sleet to describe, as he does, all the little detailed conveniences of his crow’s-nest; but though he so enlarges upon many of these, and though he treats us to a very scientific account of his experiments in this crow’s-nest, with a small compass…

Moby Dick, Chapter 35, “The Mast-Head.”

The detail of the crow’s nest is a nod to Scoresby’s father, who introduced them to ships in 1807. And while Captain Sleet was mocked in Moby Dick for being serious, Scoresby’s observations could be poetic as he was an adept writer. In a description of iceberg precipices, he writes that there was purity and beauty in “the sloping expanse” that is “covered with a mourning veil of black lichen, with the sudden transitions into a robe of purest white…” It was unusual for a whaler to be highly educated as he was.

A dangerous career and personal tragedies

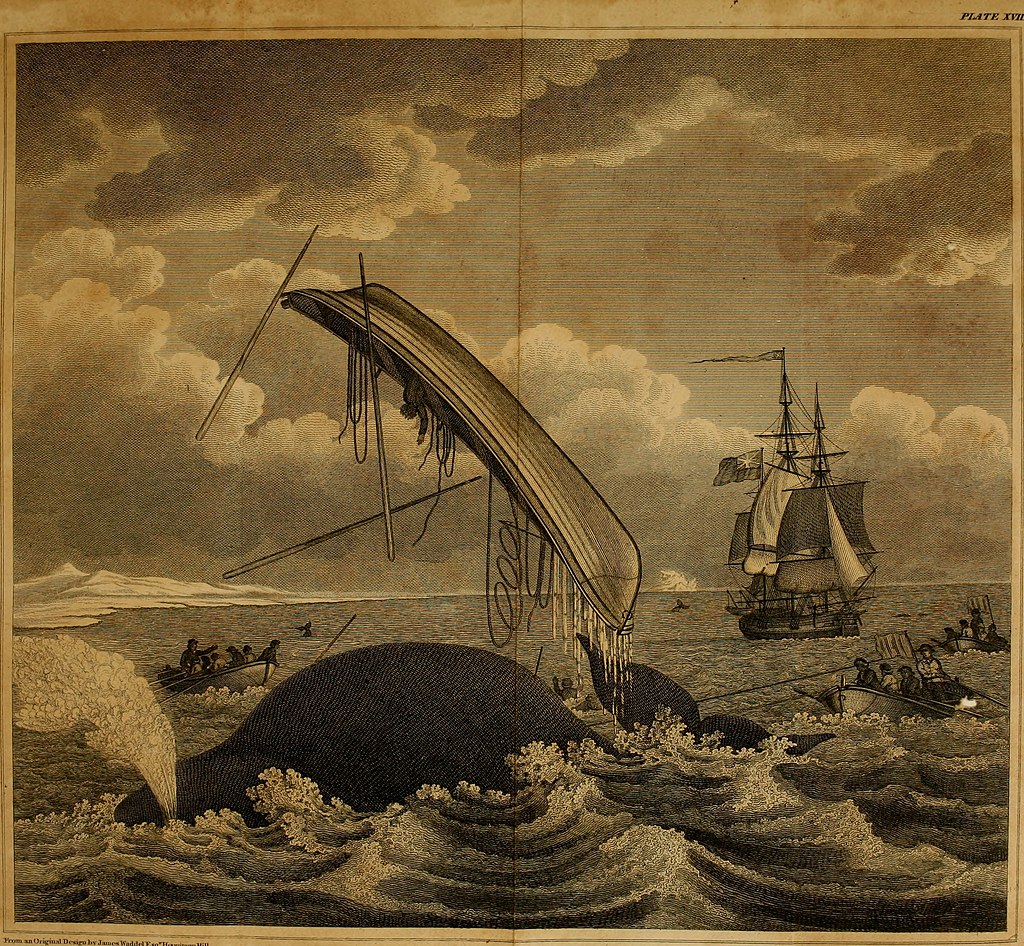

Whaling was a lucrative yet treacherous endeavour. Scoresby offers a rich depiction of the fight between man and whale in An Account of the Arctic Regions and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery (1820), which is considered “the finest account of the Arctic whale fisheries ever written” and “one of the most remarkable books in the English language.”

For man to attempt to subdue the animal whose powers and ferocity he regarded with superstitious dread, and the motion of which he conceived would produce a vortex sufficient to swallow up his boat.

In Journal of A Voyage to the Northern Whale-Fishery (1822) he recounts the moment a harpooner was drowned.

A turn of the line flew over his arm, in an instant dragged him overboard and plunged him into the water, to rise no more! It is scarcely possible to imagine a death more awfully sudden and unexpected.

But the tragedies that pocked his life weren’t prompted by whales, or even the sea. Instead, his character would be shaped by the cruel particulars of his personal life.

“There’s all these conflicting points about him,” Routledge says. He was described as a “gentle man and loved by all who knew him.” He was also someone who “was full of energy” but was also prone to being self-absorbed and tedious. He was married three times, but none of his children outlived him. He had three sons, William, Frederick and Henry; William and Frederick survived early childhood but would die aged 25 and 13, respectively. Henry died soon after birth in 1820. In a letter to her brother and sister in July 1820, his wife Mary Eliza wrote:

My dear Children too I am happy to say are quite well. I bathe my sweet Fred every day, he grows a most attractive child [...] I often wish his dear Papa was here to see his little winning tricks. I hope now that wish will soon be accomplished…

She was pregnant again in 1822, when he was on the Baffin voyage that became Journal of a Voyage to the Northern Whale-Fishery. He received a letter telling him that his infant daughter was stillborn — it’s not known if she died in the womb or during birth. What he didn’t realise was that Mary Eliza had also died. He found out four months later, on his return to Liverpool. “It’s really heart-rending,” Routledge says.

A longing for Arctic exploration

Scoresby designed the Baffin, which had been built in 1819, on a yard that became Albert Dock at the cost of around £10,000 — almost a million pounds in today’s money. He moved from his home in Whitby to Liverpool to oversee its construction, living on Stanhope Street and later at a site that was developed into Lime Street Station. It was a state-of-the-art sailing ship, made with iron cables — instead of hemp ones — and its shipbuilders Mottershead and Hayes sought only the very best materials.

“His ideas were less to do with whaling and more to do with research,” Routledge says. In 1818, the British Admiralty — the government department responsible for the Navy — had decided to renew its exploration of the Arctic — particularly the search for the coveted Northwest Passage, which if discovered would unlock a new trade route for Britain and fast-track its prosperity. The Admiralty’s decision was “strongly influenced” by Scoresby’s advice, writes Constance Martin in a 1988 edition of the journal Arctic.

“I think he was trying to fund his own Arctic exploration,” Routledge says of the Baffin’s construction. “I’m not sure how honest he was with the other investors — if you were investing in a whaling ship, you really wanted a return on your money, which you weren't going to get from taking measurements of Greenland.” In 1834, the maritime artist Francis Hustwick painted the Baffin. Hustwick’s paintings are appropriately dramatic, capturing the grandeur of ships, pitching in bottle-green seas and set against stormy backdrops. In his painting, the Baffin forges ahead in choppy waters, flanked by two other ships. Its sails seem to billow out like the sweeping cumulus clouds in the distance. As the small fleet sails on, a polar bear, dwarfed by the ships, watches from a snow-encrusted shore. The artwork now hangs in the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull.

Despite his wealth of knowledge, Scoresby was turned down by the Admiralty when he offered his services in the hopes of going on a British expedition to the Arctic. A contributing factor may have been a disagreement with Sir John Barrow, the second secretary of the Admiralty and the “main organiser” of Arctic exploration.

Sir John believed the polar region “harboured a warm water sea.” Scoresby, having spent some 17 years making notes on the region, thought this theory was a “ludicrous chimera.” One of the prevailing theories about the Pole at the time was that it was ice-free. “Anyone who had been near it knew it was wrong,” Routledge says. “But the Arctic was the last remaining part of the world where you could make speculations.” The theory persisted into the late 19th century, partly because there had been many failed expeditions to find the Northwest Passage.

There was also the issue of class: it’s perfectly possible that the Admiralty looked down on Scoresby, the son of a North Yorkshire farm labourer-turned-whaler. He longed to be a part of the British search for new polar routes, but it never happened. Despite receiving little support from the Admiralty, he managed to complete his survey of Greenland’s shoreline between 69° and 75° north latitude becoming “the first to lay down the coast with any pretence of accuracy,” Constance Martin writes.

A section of the East Greenland coast was named the Liverpool Coast, and there is the Scoresby Sound, which was mapped in 1822 with the Baffin. "Liverpool enabled some of the most important research into the Arctic,” says Routledge. “It was an outward-looking place — it comes off badly in comparison to places like London, but it was trying to explore.” When researching this piece, I was struck at how Scoresby’s time in Liverpool was barely mentioned in some of the academic journals I read, even though he created an important legacy here.

The Admiralty’s insularity defined the doomed Franklin expedition in 1845, when the ships HMS Terror and HMS Erebus became trapped in slow-crushing ice packs. It was the worst disaster in British polar exploration history. The crew abandoned their ships and attempted to make an overland trek, the weakened men dragging heavy lifeboats over rocky terrain. Searchers’ accounts painted Sir John Franklin as an example of “imperial arrogance” — all 129 men died. In Dan Simmons’ novel The Terror (later adapted into a TV series), the shivering, starving and lead-poisoned crew are hunted by a monstrous spirit, a Tuunbaq, which was based on a creature from Inuit mythology.

In 1850 the Arctic Committee went to Scoresby for help — Sir John Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin sought out Scoresby’s counsel two years before them in 1848. She understood that whalers had an intimate understanding of the Arctic, as they sailed there often. Scoresby penned The Franklin Expedition in 1850, a report intended to bolster support for further rescue missions. Constance Martin writes that Lady Jane Franklin had “deep respect for his knowledge”, reflected in her comment, “He was always my hero.”

The end of Scoresby’s whaling career

Though the British whaling industry was at its peak in the 1820s, in Liverpool it was starting to decline. Liverpool was not an ideal whaling port. Others like London, Hull, and Whitby were on the east coast of England. In contrast, Liverpool ships could be prevented from leaving for days due to the prevailing westerly wind. Between 1750 and 1823, there were 420 Liverpool whaling voyages. In 1820, there were only three whalers sailing from Liverpool. When Scoresby’s father retired from whaling in 1823, whales were becoming scarce because they had been hunted so much.

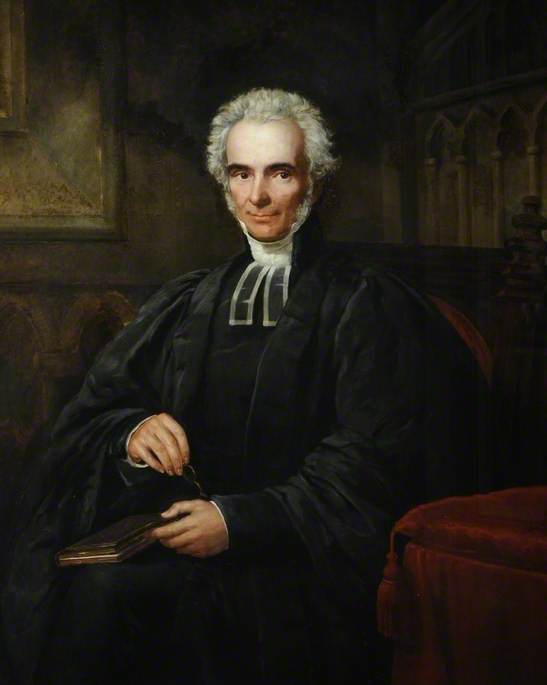

In the same year that his father retired, the Baffin sailed for the last time. By now, it was the last Liverpool whaler. The voyage lasted for five months, and in the Baffin’s logbook, Scoresby recorded the weather and ice conditions, whales caught, and navigational details. He retrained as a clergyman and became the first chaplain of the Mariner’s Floating Church in 1827. Routledge thinks it’s possible that Scoresby once again provided Melville with some inspiration for the description of the chaplain in Redburn (1849) — the two had never met, but Melville knew of Scoresby. The floating chapel is depicted in the novel.

This was the hull of an old sloop-of-war, which had been converted into a mariner’s church. A house had been built upon it, and a steeple took the place of a mast. There was a little balcony near the base of the steeple, some twenty feet from the water; where, on week-days, I used to see an old pensioner of a tar, sitting on a camp-stool, reading his Bible. [...] The floating chapel recalls to mind the “Old Church,” well known to the seamen of many generations, who have visited Liverpool.

Redburn: His First Voyage, Chapter 35, “Galliots, Coast-Of-Guinea-Man, And Floating Chapel”.

Though his dreams of joining the British Admiralty in their search for new polar routes were never realised, his career as a whaler on the Baffin in Liverpool meant William Scoresby Jr was able to carry out some of the most influential research into the Arctic. This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Journal of a Voyage to the Northern Whale-Fishery.

Unlike Captain Ahab, whose life was consumed by the maniacal pursuit of a white whale, Scoresby left his life at sea behind, though he was never far from it. He spent his final years in Torquay, on the balmy southwest coast. He is buried on dry land, where his father first tried to put him safely — back before the whales, before the Arctic, when he was just a boy: a triumphant, curious stowaway.

Comments

Latest

As Chinese car-making booms, Liverpool spots a chance to reindustrialise

Rent hikes, VHS tapes and a controversial screening of Jaws: Inside the fight over Toxteth TV

Is Liverpool resting on its laurels?

From Hoylake to St Helens, community cinema is making a comeback

In search of Leviathans

The story of a Liverpool whaler who explored the Arctic