Kensington's cannabis king Gary Youds is free from jail...again

'He’s the Phoenix, he’s Rocky, he just keeps on coming back'

Listening to Jia Zhuang talk about Gary Youds is like listening to a close friend undergo an epiphanic revelation during an acid trip in a bathtub at a house party. Or a disciple on a hill blinded by a blazing white light. Youds, Jia tells me, is not a revolutionary in the Che Guevara sense of the word — a bloody-minded warrior for his cause. If he was to select a more appropriate revolutionary, then Mahatma Gandhi would perhaps be his choice. Peaceful, kind, wise and — crucially — ahead of his time.

“Do you know the meaning of the term ‘antifragile’?” Jia asks me. I do not. Fragile people, he explains, shrink in the face of difficulty. Resilient people, conversely, let difficulty bounce off them. But antifragile people, well, whatever life throws at them they grow ever stronger. “Gary is antifragile,” Jia tells me. “He only comes back more vibrant”.

Mark, another of Youds’ supporters, paints a similar picture. “He’s the Phoenix, he’s Rocky, he just keeps on coming back,” Mark tells me. “Gary can take people to water — they’ll follow him.”

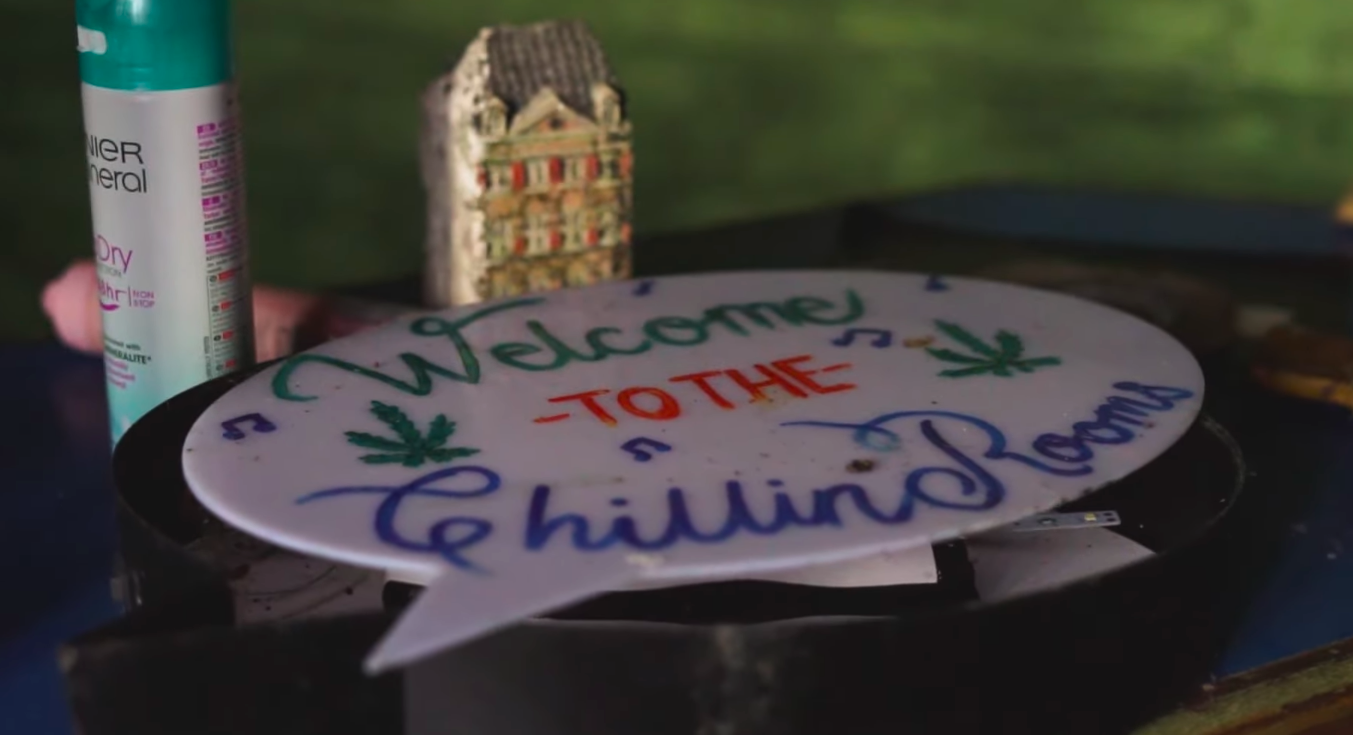

It’s been more than a year since I first heard of Gary Youds and decided I wanted to write about him in The Post. I’d heard about his Chillin Rooms cannabis cafe in Kensington, a clandestine business often described in gushing, almost quasi-religious terms. But before I could grab my lighter and check it out for myself, I learned that Gary had been sentenced to three years behind bars. He was off to HMP Altcourse, where he would be spending the foreseeable.

It was a blow for me, though to be fair, a bigger blow for Gary. He’d been caught at Liverpool Lime Street Station with 40 syringes of cannabis oil, two spliffs and a tobacco pouch containing around six grams of cannabis resin. Police later raided his house, finding a “quantity of cannabis with a street value of up to £7,000.”

The issue was that Gary had a record. In fact, he had a record that unfolded like a Mediaeval scroll. He has been to prison four times, all for cannabis-related offences, and he’s had his house raided more times than he can remember. The Chillin Rooms in Kensington has bounced in and out of existence since 2005, repeatedly shut down by the authorities only to spring back up when their backs were turned.

In emails sent from his cell to close friends like Jia, Gary remained steadfast about the path he was on. As he wrote, “all revolutionaries go to jail”.

A small but resilient campaign group formed to protest for Gary’s freedom. Jia, of course, was at the forefront. Two songs were released, “Free Gary Youds” and “Release Gary Youds”, by rapper Spam Hoolie, and £2,500 was raised via crowdfunding.

Then, at the end of February, after serving a year of his sentence, Gary was free. Jia was among a number of people there to meet him at the prison gates. “His face had this glow,” Jia says. He asked Gary if he felt resentful. Gary said he didn’t. “He just wants to bring the peace back,” Jia says. That night, they stayed up late just “smoking and chatting”. The phoenix had risen again. This time, though, Gary would do things right. No more going back to prison. It was time to make real change.

It’s a Thursday morning when I make my way to north Liverpool to meet Gary. I find him at home, gradually re-adjusting to ordinary life. The weeks since his release have been hectic, full of Zoom calls and visits from the national press. The other day he opened his front door to find reporters from the Daily Mirror standing around outside. A few days later, the well-known presenter Matthew Wright used Gary’s story on his LBC radio show. The Echo have called him a “cannabis martyr” and published a separate article saying their readers believe he should be awarded a knighthood.

As for Gary himself? Well, he tells me he just wants to “see peace”. And he’s got big plans.

First though, a brief (potted!) history of my own relationship with weed. Back when I was 16, when sitting on park benches with bottles of White Lightning was beginning to go out of fashion among my friends, I briefly rebranded as a Weed Smoker™. It began with me waiting by a disused storage unit down the road from my nan’s house for an older boy known to us as “The Don” (Bran-don) to turn up. He was always very, very late. It ended with me waking one morning to my mum hovering over the bed, waving my mobile phone in her hand after discovering my texts to the dealer. Nowadays, it’s lost its appeal. I’ll smoke out of absolute necessity, such as in the process of trying to impress a girl, but little else will persuade me. I certainly can’t lay claim to any groundbreaking or life-altering revelations, which is a shame.

Why this interlude? Well, when you’re stepping through into Gary Youds’ world as someone who doesn’t really get it, you have to leave all preconceptions at the door. In the Chillin Rooms, weed does not mean 17-year-old boys called Bran-don making their baby steps into the world of crime, prison sentences and the like, funded by 16-year-old boys like me, whiteying on the end of a pier. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. The Chillin Rooms exists, Gary tells me, in direct opposition to the illicit drugs trade. “It’s a kind of paradise,” he says.

But what is the price of paradise? Before all this, Youds was a successful man. Alongside his twin brother, he was the director of a property company valued in the millions having built houses and flats all across north Liverpool. He had a Mercedes. But after attending a cannabis conference in 2002, he founded the Chillin Rooms, his illicit Kensington cafe, advertised only by word of mouth. Soon, they were getting 300 people in a night. When the raids started, Gary dug his heels in. After that, his brother “basically disowned” him. The last time they spoke was 10 years ago, by which time Gary had long since resigned as a director, forced out by proceeds of crime laws. “He thought I was a druggie and a waster and a loser,” Gary says.

The martyr tag that often gets attached to Gary may seem like an exaggeration, but make no mistake — this is a cause, and not just for him. Jia tells me he walked away from a lucrative career as a product manager in tech in London in order to join Gary in fighting the good fight. He hasn’t been on holiday or bought new clothes in six years. “I don’t really need very much to survive,” he tells me.

Jia’s epiphany came when he first met Gary before the pandemic. He’d travelled up to the Chillin Rooms from London, and — despite being shocked at the deprivation of the surrounding area in Kensington — he was enamoured by the cafe. “Gary was at peace,” Jia tells me. “He was on the righteous path.”

The Chillin Rooms has this reputation. “I’ve never experienced a euphoric high like being in there,” Gary says. He describes it as a “genetically modified” space: he fitted every screw and every bolt. Jia tells me it’s a “cathedral”, given the church pew-style seats lining each side of the room. Jia’s first night there, he says, was one of the best of his life.

This might sounds peculiar to some. A man (who still lives in London) chucking in a successful career in order to support a cannabis cafe on the other end of the country. The quasi-religious references. But Jia sees this as part of who he is. Though he grew up in the UK, Jia was born in China, and has spent a long time researching cannabis usage in traditional Chinese medicine. He’s read the ancient texts. “Cannabis for me is part of my cultural heritage,” he says.

What’s more, he tells me, Gary is a healer. His arrest — the most recent one, that is — only happened (to quote Matthew Wright on LBC) because he wanted to help “the sick and dying”.

Gary had come across a man called Alan Tisdale at an activist conference. Tisdale was terminally ill. He had cancer and his son and daughter were accompanying him to the conference as they’d heard about the use of cannabis as pain relief. Gary agreed to help. He began supplying Tisdale with oils, which — Gary tells me — improved his quality of life dramatically. He was on his way to Birmingham to meet Tisdale the day he was apprehended by four undercover officers at Lime Street (Gary wasn’t even letting Tisdale pay his train fare).

Gary saw real horrors in prison. Fentanyl use was widespread in HMP Berwyn — if the drug would cause somebody to go “man down” (meaning they’d collapse or pass out), it was seen as a selling point. There was also the violence. “People just hitting each other, mindless, mindless, violence,” Gary says. “I just sort of hid myself behind my door, but I heard the screams and I saw the blood outside — and what you can see outside your little flap.” For the first six weeks he was kept in his cell, suffering nightmares. Gary’s done the calculations, and reckons that his time being processed through the courts and then imprisoned cost the state around £250,000. This is, after all, for a drug that is legal in Canada, Germany, Malta, Mexico, South Africa, parts of America and various other countries.

“We get hunted down, we’ve got no dignity. We get villainised and stigmatised and ostracised every day,” Gary says. Now, he has a solution. No more arrests. No more raids. No more operating the Chillin Rooms under the cloak of darkness. He’s turning his cafe into a harm reduction centre and launching a career in politics. “It’s time for real change,” Gary says.

Mark is preparing to help Gary run for parliament at the general election this year. “I think last week — and don’t want to be mentioned in the same breath — but George Galloway’s victory in Rochdale shows our point, really,” he says. That point is that he believes cannabis legalisation could be effective as a single issue vote-winner, just as Gaza was for Galloway. Mark is hoping their new party (as yet unnamed) could stand in most major cities. Ambitious stuff, he accepts, but like Jia, he truly believes in Gary. “I’ve met a lot of people in this game but Gary is so convincing, he’s an evangelist,” Mark says.

Gary is clearly right about this: the illicit drug trade has ruined communities all over Liverpool, all over England. Violence, overdoses, deaths, children growing up without mothers and fathers, endless police resources and a cycle that only goes round and round. Whatever the solution is, it’s not the one we’re currently pursuing. A couple of weeks back, Germany became the latest country to legalise the drug for recreational use. Perhaps the tide of time is in his favour.

Jia, meanwhile, is continuing to develop an app he and Gary have been working on for some time. It’s called The Cannabis App, of course, and it provides a community for users to discuss legalisation and home-growing. Jia might not live the high life anymore (depending on your definition of the phrase, anyway), but through Gary he seems to have found himself — following in his mentor’s footsteps, walking the righteous path.

Comments

Latest

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still play every Saturday

Does Liverpool have a ketamine problem?

The other Liverpool

Kensington's cannabis king Gary Youds is free from jail...again

'He’s the Phoenix, he’s Rocky, he just keeps on coming back'