It started as a day of remembrance. Then fear and confusion reigned

Our account of Sunday's attack, based on the experiences of people who lived through it

Dear readers — tonight’s story is an account of Sunday’s bombing at the Women’s Hospital. Based in large part on people we’ve spoken to since the attack and information released by the authorities, it’s a story about how one shocking event rippled out across a city, upending lives and spreading fear.

We were going to be publishing our first members-only story today, but that will now come on Thursday. You can join us as a member by clicking the button below. Welcome to all those who joined last night.

By Harry Shukman, Mollie Simpson and Joshi Herrmann

Twenty minutes before 11am, Liverpool’s service of remembrance got underway at the Anglican Cathedral. The Worshipful Lord Mayor, Mary Rasmussen, was there to lead the city’s tribute in front of almost 1,200 attendees. Big screens in the grounds broadcast proceedings, making this one of the largest Remembrance Sunday services in the country. A parade, planned for after the service, closed local roads.

The cathedral was filled with military veterans, serving personnel and families of the fallen. At the lectern, Craig Lundbergh, a former Lance Corporal who lost his sight and almost his life in Iraq, spoke about sacrifice. Watching him were Joanne Anderson, Liverpool’s mayor, Serena Kennedy, the chief constable of Merseyside Police, and Phil Garrigan, head of Merseyside Fire and Rescue Service.

Liverpool's remembrance service normally takes place on St George's Plateau, but the chaotic building works around Lime Street forced a change of location. It was on Armistice Day, last Thursday, that local dignitaries placed flowers in front of the low-relief bronze sculptures of the Cenotaph, upon which is etched a line from Samuel: “The victory that day was turned into mourning.”

Nineteen minutes after the service began — at 10.59 — police were called to the Women’s Hospital. From inside the building, patients and staff could see a car that was engulfed in flames.

One new parent chose not to tell his partner about what he had seen. David Perry, the taxi driver whose car had blown up, was in shock as medics treated his injuries. Understandably, not everything he was saying made sense. And within minutes, rumours about what had happened were spreading through the city.

Back at the cathedral — a five-minute drive from the hospital — the service came to an end without interruption, but the march was delayed. Attendees were told there had been a medical incident. Richard Kemp, the leader of the Liberal Democrats in Liverpool, looked around for the chief constable and the chief fire officer, but he couldn’t see them.

Both had been told about the explosion, and left the cathedral via a side door. Meanwhile, the service organisers switched to a backup plan that had been organised well in advance. The march was re-routed to a different cathedral entrance, one which is considered more secure. Most of the marchers and those watching them had no idea what was going on just down the road.

According to law enforcement sources, Merseyside Police will have involved Counter Terrorism Police North West, the team that handles regional terror threats, who in turn will have involved MI5. That meant that very quickly, the decision-making for an incident that was gripping Liverpool was transferred to Manchester, where the counter-terror team is based. Journalists were soon redirected to the press office at Greater Manchester Police.

The public had to wait more than 24 hours to learn the identity of the bomber, but the blast held its own clues. Shortly after footage of the blazing taxi started to circulate on social media, security experts consulted by The Post said the size of the explosion, which caused more fire damage than blast damage, suggested the crudeness of a homegrown attacker and not a seasoned terrorist with overseas training or foreign backing.

‘Don't you fucking move’

The torpor that normally prevails on a Sunday afternoon in the Sir Walter Raleigh pub in Kensington was interrupted by police sirens. At around 3pm manager Kerri Shaw and five of her regulars ventured outside onto Boaler Street to see what the fuss was about.

“Get back, get back! Move away from the windows!” yelled a police officer, ordering them to go inside and lock the doors. The regulars tried to make light of it — “let’s get pissed”, one of them joked — but Kerri, who suffers from anxiety and PTSD, felt like a “nervous wreck”. Her dad kept calling to see if she was OK and she did her best to reassure him.

After an hour, she spotted officers leading a man in handcuffs around the corner from the terraces on Sutcliffe Street. The man – one of the three arrested that day – was placed up against the wall of her pub. Her emotions boiled over, and she started shouting at him. “Scum! Rat!”

Kerri doesn’t tend to drink, but when police came back and told her it was safe to leave, she shut the Raleigh for the night, walked to a nearby pub and necked two shots of Sambuca. It did nothing to settle her nerves, and she went on to spend a sleepless night at her parents’ house.

Near her pub, residents on Boaler Street had witnessed the arrests at close quarters. They were settling in for the evening and starting to make tea when they noticed armed police converging on a neighbouring house.

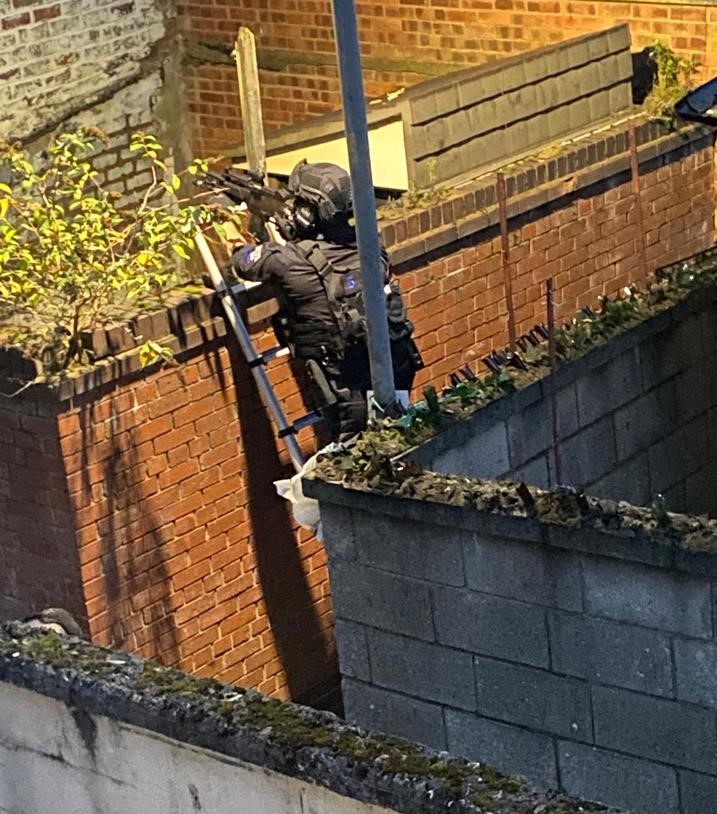

Sharon Cullen’s daughter spotted an armed police officer standing on a ladder aiming his weapon over the garden wall — and called her over. Their home shares a back alley with Number 2 on Sutcliffe Street, and around 4pm Sharon snapped a photo of the officer on her phone. The next hour was a blur before they heard shouts from outside. “Armed response! Get on the floor!”

Sharon’s direct neighbour, a glass factory worker from Poland named Martin Czyz, also pointed his phone at the scene just beyond his garden. His footage — which was soon racing around local WhatsApp groups — shows the arrest of one of the three men from the Sutcliffe Street house.

"Armed police! Don't you fucking move! Show me your hands now! Show me your fucking hands!” It was dusk at this point and the video shows police torchlight skittering around the brickwork of Number 2’s back wall. Officers booted down the wooden door connecting the alley to the garden. “Hands on your head, hands on your head! You walk towards me! Slowly! You walk towards me now. Keep coming! Face the wall!”

A young man comes out of the house as police rush towards him.

‘It could blow the block’

Rutland Avenue is a leafy street of spacious semi-detached homes, just up the road from Sefton Park and populated by plenty of academics and young professionals. “Relaxed and calm,” is how one local councillor characterises the road. But by the late afternoon on Sunday, it was anything but.

The taxi that exploded outside the Women’s Hospital had picked up its passenger from an address on Rutland Avenue. That was one of the first pieces of useful evidence investigators got. As dusk fell, the police presence on the road grew alarmingly. The road was cordoned off and officers were seen pointing guns at houses. Around 8pm, an Echo reporter at the end of the street spotted what looked like police negotiators entering the cordon. The notion spread that there was a stand-off.

Fears over explosive material left in the bomber’s flat prompted officers to evacuate the houses next to his, and order residents further away to stay indoors. Around 11pm in the evening, 18 residents were hurried out of their homes — some were taken to a leisure centre in Wavertree, which operated as a makeshift respite, and others went to their families or checked into hotels.

Two young couples living together — Iden and Emel, Mette and Ersin — were unwinding from work on Sunday night when police told them to leave immediately, and that there was no time to get changed. Iden grabbed a coat to wear over her pyjamas, and Mette left wearing his Pizza Hut uniform. A council worker approached them outside and said they would pay for a night in the Hilton down by the docks. “So much better than my house,” Mette joked.

On Cumberland Avenue, one street east of Rutland, Amina’s house backed onto the bomber’s. She had never seen him coming or going, but noticed that the lights were “constantly on” and thought from seeing ladders outside that he was doing plenty of DIY. On Sunday night, as the house became the focus of intense activity, Amina was evacuated.

The discovery of “significant items” at the Rutland Avenue address set off a chain reaction on Sutcliffe Street, where the arrests had taken place. A cordon was set up barring residents from leaving their homes, but those who live closest to the address in question were rushed out by police.

Sharon, who lives with her husband, daughter, and grandson, was told she had to leave her house immediately — and just had time to take her coat and the handbag that carries her medication before leaving for the night. The officer ushering her out said: “Whatever is going on at the back of the house, it could blow the block.”

A day of answers

It would be a day and a half before the bomber was named. Emad Al-Swealmeen, a 32-year-old man born to a Syrian father and an Iraqi mother, arrived in Liverpool approximately seven years ago.

Part of that time was spent living with Malcolm and Elizabeth Hitchcott, two devout Christians from Aigburth, who lamented that their cheerful lodger had become a “waste of a life”. Swealmeen had applied for asylum in 2014, but was refused after he was sectioned during what Malcolm described as a "mental health incident" in which he waved a knife at people from an overpass.

Those details emerged late in the day, and the Hitchcotts were interviewed on the evening news. Around the same time, police announced that they had released the four men arrested on Sutcliffe Street without charge. The authorities are “satisfied with the accounts they have provided and they have been released from police custody”.

The release of the four men leaves massive questions hanging over Liverpool’s attack. Was the hospital the intended target, or did Swealmeen plan to go to the service itself? Was he a lone wolf? The police have warned that some of the answers in this case won’t emerge quickly.

Among the information furnished by the Hitchcotts was a striking detail about the bomber’s conversion to Christianity in 2017. It took place at the Anglican Cathedral — the place where Sunday’s day of remembrance began before the city was convulsed by terror and panic.

Comments

Latest

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

I’m calling a truce. It’s time to stop the flouncing

The carnival queens of Toxteth

The watcher of Hilbre Island

It started as a day of remembrance. Then fear and confusion reigned

Our account of Sunday's attack, based on the experiences of people who lived through it