Campaigners and bereaved families wanted a Hillsborough Law. Six years later, the government says this isn’t necessary

On why the Hillsborough Charter doesn’t go far enough

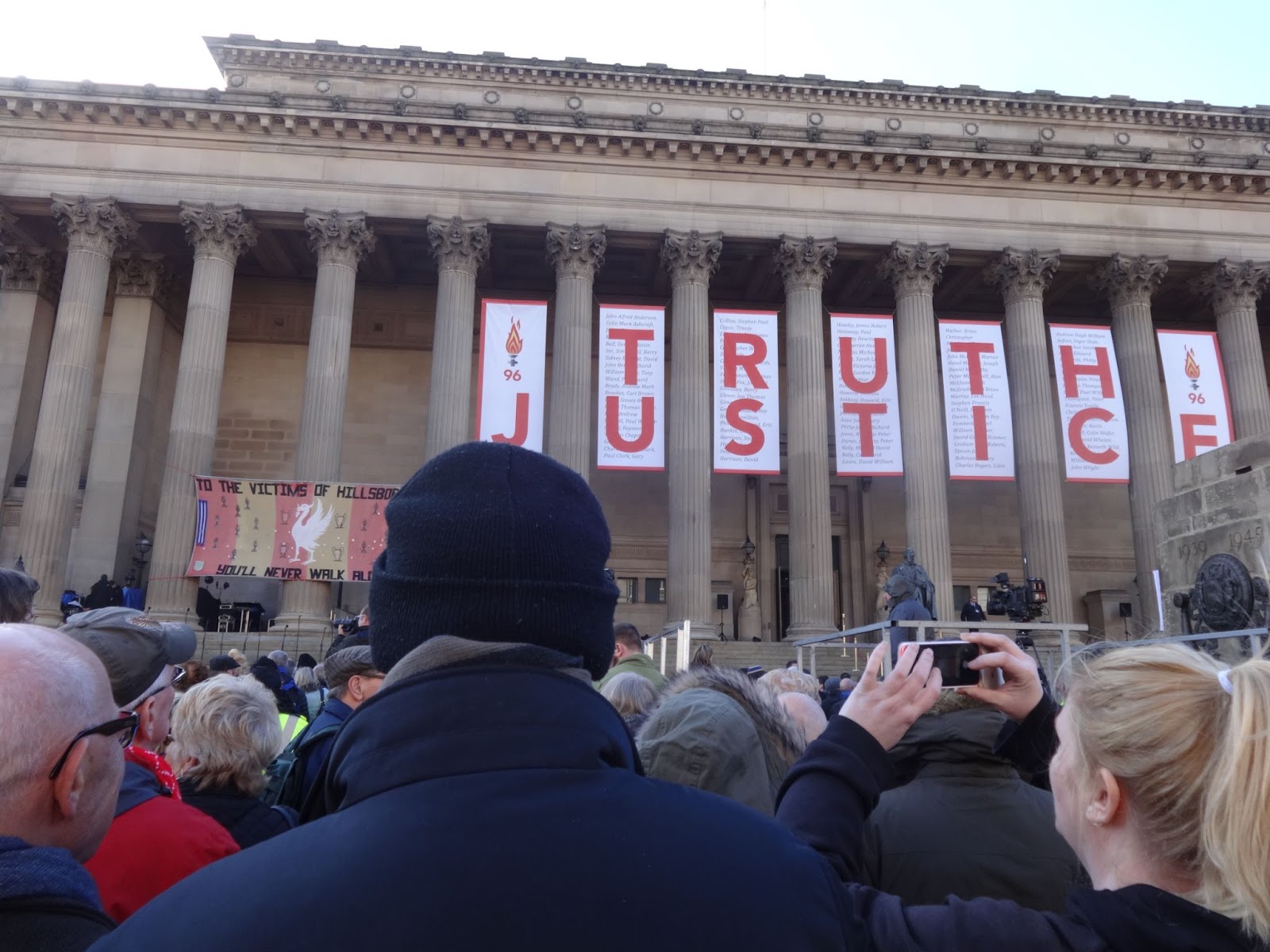

Dear readers — normally, our Tuesday feature goes behind a paywall. But we believe this piece is so crucial that we want the largest possible number of people to read it. Six years ago, the former Bishop of Liverpool, James Jones, published a report about the failings that took place following the Hillsborough disaster. The crush at the stadium sparked the longest inquest in this country's legal history. For decades afterwards, South Yorkshire police insistently denied any responsibility, scapegoating the fans for what had happened.

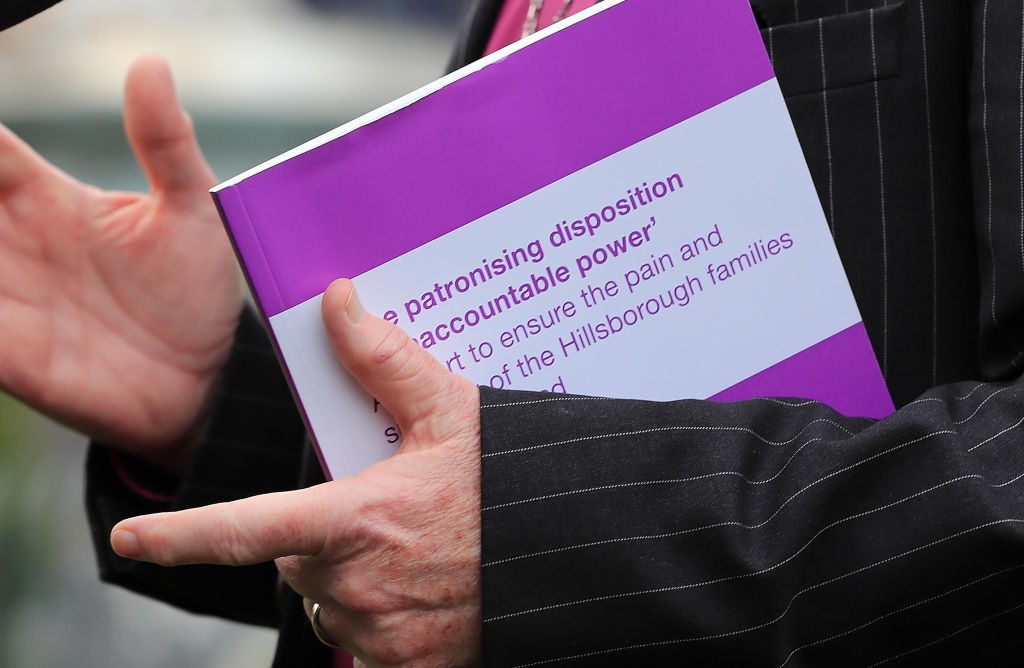

Jones’ report aimed to learn from the years of disappointment and frustration — so that we could prevent the lies and omissions of fact that we saw in the wake of tragedy from ever taking place again. Two weeks ago, the government published their response (a response that comes a huge six years after Jones’ report). In this, they seem to imply that the families and campaigners are mistaken — that a Hillsborough law is not necessary, and that a Hillsborough charter is the answer.

We sat down with constitutional law experts, solicitors, and MP Maria Eagle to scrutinise this claim. But before that, our Post briefing — including progress at the former Littlewoods site and a tribute to Sir Ken Dodd.

Your Post briefing

Plans have been submitted for a Happiness Centre in honour of Ken Dodd. The centre, containing a permanent exhibition in memory of the Liverpool comedian, would be built at the existing Courtyard Bar next to Liverpool’s Royal Court and include a statue of Ken Dodd with his tickling stick outside as well as a workshop space, bar and cafe.

Liverpool is finally set to get a tap-and-go system for use on buses, trains and ferries after nearly £10m was approved by the Combined Authority to simplify the city region’s ticketing system. Alongside the tap-and-go system will be the ability to make contactless payments and set fare capping in the future. Metro mayor Steve Rotheram said that while the plans had been in the offing for a while, they’ve been “accelerated” due to customer demand.

Diggers have been arriving on site at the former Littlewoods building as part of its transformation into the Hollywood of the North. Work is beginning to preserve the building’s iconic facade ahead of its transformation into a film and TV studios. Head of Liverpool Film Office Lynne Sanders said the “truly transformational” project will “change people’s lives”. You can watch the full video of the diggers arriving on site here.

Campaigners and bereaved families wanted a Hillsborough Law. Six years later, the government says this isn’t necessary

‘I felt the families were conned. We were told that our questions would be answered at the “generic” inquest, but they weren’t.’

‘I had a telephone call from the then South Yorkshire Chief Constable... During the call he said “I am under no obligation to disclose anything and the papers belong to me. If I wanted to I could take them into the yard and have a bonfire with them”.’

‘After the Panel report, I took the report to the cemetery and said, “Look, Mum, he was not a hooligan.” The Panel found out the truth.’

The voices above are just three of those who lost family members in Hillsborough, the largest ever sporting disaster in the UK. They were quoted in the report the former bishop of Liverpool, James Jones, published in 2017 — this was a report which aimed to learn lessons from the damage done in the aftermath, when lies and omissions by police and ambulance services meant the reality of what happened was covered up. Jones’ aim was to consult with the families and make recommendations for change. On December 6, the government finally issued their response to his recommendations — six years later.

The public reaction has largely been one of disappointment. The response of the national press has been fairly muted — while the nationals have reported the disappointment on the part of the families, they haven’t really grappled with the 82-page document in the detail it requires.

Here at The Post, we’ve spent hours poring over the government’s response, the Hillsborough Law that was proposed and the Bishop’s recommendations. We’ve also consulted constitutional law experts to try and get to grips with just how far these proposals diverge from what Jones suggested in his 2017 recommendations and from what families have called for. Are there any reasonable grounds for these forks in the road? Where do the proposals fall short? What, in essence, should be put in place to stop the aftermath of Hillsborough – a whirlwind of mass deception — ever taking place again?

Just to prepare you — this is very different writing than the sort of articles we usually put out. We have tried, where possible, to translate the legal language into its more everyday equivalent. We think the subject matter is so important that a deep dive into the law is required. We hope you’ll stay with us until the end.

The shortest version of what has taken place is this: families, campaigners and Jones’ report proposed the Hillsborough Law, which would have created a legally binding obligation to tell the truth. In addition to this, Jones recommended a Hillsborough charter, he also recommended a duty of candour for all public-sector workers. The government have committed to all public sector bodies and officials signing just a Hillsborough charter — where anyone who signs must try to abide by its key principles (which include, amongst others, activating an emergency plan in the event of a tragedy, putting the public interest before the government’s reputation, handling public scrutiny with candour and taking care to avoid past mistakes) — but stopped short of agreeing to the law or key measures within it.

The government's response insists that existing laws and regulations leave "no gaps" that need filling by a Hillsborough Law, making its creation unnecessary. However, legal experts we spoke to, including the man who wrote a draft Hillsborough Law rejected by the government, strongly disagree with this interpretation.

The problem with creating a charter but not a new law is that, at worst, it can only inflict a gummy and toothless bite. Bill Dunkerly, an associate partner at the Manchester-based legal firm Pannone Corporate puts it succinctly: “There’s no stick.” He points out that, except for the situations where people giving testimony are required to take an oath (so, for example, in inquests or statutory inquiries), not complying with the “duty of candour” expressed in the document — the idea that you’d answer questions honestly — wouldn’t mean that you’d face jail time for lying.

It’s a charter, not a written law, Bill emphasises. “If there is a breach of it, there’s a question as to what the consequences of non compliance are.” In his view those consequences are likely to amount to “not much at all.” Garston and Halewood MP Maria Eagle, who has pushed for years for the introduction of an independent public advocate (something we’ll come back to later), seconds this take. The problem is the charter is “all voluntary,” she tells us.

This matters. “Under the pressure of suddenly having to deal with a disaster, and its aftermath where you think you might be going to be blamed, that's when you look at what the law says, not at what your code of conduct says,” says Eagle. And in fact, we can see this quite clearly with Hillsborough match commander David Duckenfield, who in 2015 admitted to lying about giving the order to open a gate at one end of the football ground, claiming that fans had forced it open. When asked why he had lied, he explained: “I was probably deeply ashamed, embarrassed, greatly distressed. I probably didn’t want to admit to myself or anyone else what the situation is.”

Human rights barrister, Peter Weatherby, who has represented 22 of the victim’s families and is a director of lobbying organisation Hillsborough Law Now, is rather more damning, calling the government’s charter a “chocolate fireguard”. For the families of victims, the law isn't an idle ask — despite differences of opinion after decades fighting for justice, it is an issue they are all united on. Without the law, the duty of candour is not legally-binding and remains, one could argue, more of a polite request for candour.

Weatherby understands that, to those not minutely familiar with the law, insisting on a legal requirement to tell the truth might seem like an exercise in hair-splitting. “I mean, it sounds ludicrous,” he says, “but the reality is that, apart from in some very narrow areas of law, there is no actual legal imperative for people to do that.” He also points out that the government could have greased the wheels of future investigations of public tragedies — avoiding many of the issues created by the changing testimony of South Yorkshire Police — by insisting authorities had to issue a position statement at the outset.

Which is what? This is effectively the obligation for the authority to explain what happened from their perspective. Authorities currently present witness statements at inquests but a position statement differs, Weatherby tells me, in that it would be presented early in the investigation process and requires “not only disclosure, but identification of the real issues and in particular failures and wrongdoing.”

If the law had been in place when Hillsborough happened, Weatherby says, it would have required South Yorkshire Police to set out in a position statement what role they’d played, what worked “but more importantly what didn’t, what the failures were.” Participants are required to proactively tell the judge or the police their version of what happened. “Of course, what happened in Hillsborough was the police lied and lied again.”

In the law as Weatherby drafted it (in collaboration with other solicitors), position statements would have to be signed off by the chief officer or the chief executive of the relevant authority, who would be responsible for checking they are correct. While there wouldn’t be a sanction for inadvertent errors, one possible consequence for signing a dishonest statement would be jail time.

The thinking is that, with the threat of imprisonment hanging over them, whoever would be committing their signature would have a powerful incentive to check and double check every detail. Weatherby imagines them “saying to their people, are we right about this? Is this what happened? If they make a mistake, or if it's not quite right or whatever, then that will be found out in the inquiry itself. But if they lie, clearly, wilfully do so, then they would be subject to criminal sanction.”

Weatherby believes this would reduce the chances of a cover up to somewhere hovering “around the zero mark” because it would put the onus on, for example, chief constables to make sure they’ve got things right. As he puts it: “No Chief Constable or chief executive in their right mind would take the risk of wilfully not complying.”

The proposed law wasn’t just designed to lessen the chances of outright lies, but also omissions. Yes, of course Hillsborough was about corruption. “It was police officers but not just police officers, the ambulance service as well, protecting themselves from their own wrongdoing,” Weatherby says. He points out that this was criminal wrongdoing, but there are many other cases where it’s not about explicit lies. “It's human weakness. It's human error. Something overlooked. And when it comes to an investigation or an inquiry, the public authority or those representing the public authority will often not so much lie as they will simply not address the point so they will mislead [the inquiry or inquest] by not addressing it.”

Position statements allow a judge or coroner to quickly get to grips with the key areas of inquiry: “You get a range of position statements from different authorities and organisations involved and you can see where they cross over and either agree or they don't. So that allows you to hone where to look.” You’re able to swerve a needle-in-a-haystack situation of having to root about in irrelevant directions for evidence or in huge document drops after years of delays as seen in Hillsborough: “You just get justice much quicker.”

All of these points really come into focus when you think about the second inquest in 2014, by which time South Yorkshire Police had already admitted their responsibility and acknowledged that the ‘hooligan narrative’ put out in the aftermath that smeared the victims, was simply not true.

But even at this point, that same hooligan narrative was allowed to be aired by lawyers acting for former police officers. So let’s take a time machine, wave a wand, everything’s different. Imagine that South Yorkshire Police had been required to give their position statement at the outset of that inquest — in which they would have clarified the statement the chief constable had made on television in 2012, that it was them and not the fans to blame, something which could have been cross referenced against other position statements. According to Weatherby, that “would have cut the legs off the former senior officers’ narrative and there was no way they could have run their hopeless defence” — it would have narrowed the scope of the inquest and cut down the time, potentially by a year, also saving tens of millions in public money and sparing the families the horrors of having to relive the baseless claims seeking to blame those who lost their lives that day.

Unfortunately, this isn’t the only way that the government’s response falls short. One version of the Hillsborough Law proposal (also welcomed by the Bishop in the 2017 report) called for the creation of something called an Independent Public Advocate or IPA. This person would do exactly what you’d hope for if you were the victim of a disaster or a bereaved family member: connect you with mental health support and financial services, ensure you understand what your rights are and that you can take part in inquiries, give you updates on investigations and advocate on their behalf in dealings with the government and public sector bodies (something which seems particularly valuable when you might not have the emotional stability in the aftermath of trauma to do this for yourself).

So, good news and bad news. Let’s start on the good: this should soon be enshrined in law, thanks to the Victims and Prisoners Bill currently going through the House of Lords. But Eagle says that, while she welcomes the move to introduce an IPA and amendments to the initial proposals that have been made so far, the government’s plans don’t go far enough. In the original version proposed to parliament by Lord Wills and later Eagle, the family member of someone who has died in a disaster can trigger this — they can choose to get access to the IPA themselves. But in the version the government is proposing, it’s the government who decides whether an IPA is needed or not, something Eagle says the government appears unwilling to budge on.

Furthermore, Eagle suggests that, ideally, you would want the advocate to be given rights as a data controller — something the government has also stopped short of doing. Being a data controller means that you’re permitted to handle documents about the private matters of other people. While this sounds dry as dust, this is absolutely essential when we’re looking at taking lessons from Hillsborough. The turning point for Hillsborough came when the Hillsborough Independent Panel was created — they were able to access documents and get them out into the public domain and “succeeded where all courts had failed to get to the truth of what happened at Hillsborough, and that was on the basis of transparency,” Eagle explains.

The MP explains that an independent public advocate acting as a data controller would be able to handle documentation where access would usually be restricted under data protection legislation. The idea is to secure relevant documents at an early stage in the process, to “not be fobbed off” and to “enable a Hillsborough independent panel type process to take place at a much earlier stage, not 23 years later when there’s hundreds of thousands of documents to sift through.”

The Hillsborough Law proposal didn’t just call for more equal access to information it also called for a more level playing field financially. Weatherby tells us that a “requirement for proportionality” was in the draft Hillsborough Law as, if you went back to the first inquests, “the public authorities were heavily lawyered”. In contrast, when it came to the bereaved, “those who could afford it had a whip round and got one barrister, who was quite junior and completely overwhelmed.” They were outgunned, he explains, and it assisted in a miscarriage of justice that continued for decades. “If you don’t get a level playing field, you don’t get justice and actually it’s far more costly in the long run.” As such, the proposal sought to establish two things concerning legal costs: transparency and proportionality.

The government has introduced the first of these, making it a requirement for public bodies to release their legal expenditure for inquiries and inquests. But when it comes to the second, while the government claims that it supports the principle “that public bodies should not be able to spend limitless public funds on legal representation” and have encouraged public sectors to be “proportionate” in their legal spending, once again, it’s stick free — there’s no way of enforcing this. They’ve not actually defined what sort of sum constitutes proportionate legal bills, so presumably they’re hoping the sheer embarrassment of having to release legal expenditure, a string of zeroes fluttering in the wind, keeps public authorities in check.

There has been one small win when it comes to legal aid for families at inquests — the government has made an alteration to rules about when victims’ families can access the funding. There are two tests for getting the funding under exceptional cases rules, which would apply following tragedies like Hillsborough — mean testing and merit testing.The government has already removed much of the means testing around these exceptional cases, and said it is consulting on further expanding legal aid provision for inquests.

This makes sense! Weatherby argues that denying legal aid is actually a “false economy” — it makes cases take longer and there’s increased risk of miscarriage of justice. We witnessed this in the case of Hillsborough, where the original injustice sparked multiple expensive, lengthy proceedings, which cost the taxpayer much more in the long run than if the families had been given that fair balance at the initial inquest.

In the government’s defence, they are not entirely alone in opposing a Hillsborough Law like the one Weatherby helped draft – they are in fact joined by some members of the legal profession. Weatherby, however, insists that some lawyers acting for public authorities are only against it because the idea of submitting a position statement would force them to “put their chips on the table, so they can't see how the case is going and move their case around to fit it.”

However, for public authorities, as Weatherby tells me and as the government’s charter affirms, ‘winning’ and defending reputations shouldn’t be the priority in such situations anyway: “Public authorities are there to do the public good, their lawyers should not be there to prioritise protecting their reputations or obfuscate processes which are designed to make things better in the future, and save lives.”

The government’s charter describes a commitment to culture change, something Eagle says is needed and welcome but simply not enough. What victims’ families and campaigners have been calling for is for the laws to be “strengthened”.

So, for those determined to see a Hillsborough Law, is there any hope? There are, Weatherby says, two answers he could give to this question. “The first is I don't have a magic wand. I can't guarantee [the campaign for a Hillsborough Law] will be successful. So the answer to your question could be that nothing can be done, now the government has rejected it.”

He points out, however, that the Labour Party has promised that it will be in their manifesto for the next election and Keir Starmer has publicly promised to enact it. Plus, he says, all the other main opposition parties and some Tories support it: “So yes, there is hope. Ann Williams, my first Hillsborough client once said to me ’They will give in before I do’.” These are glimmers of accountability amidst the disappointment, as the battle for candour rages on.

Comments

Latest

‘Cutthroats and sell outs’: An editor’s note about Laurence Westgaph’s threats

Ian Byrne: Why the country — not just Liverpool — needs the Hillsborough Law

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

The Mersey’s clean-up cost £8 billion. So why is it still so dirty?

Campaigners and bereaved families wanted a Hillsborough Law. Six years later, the government says this isn’t necessary

On why the Hillsborough Charter doesn’t go far enough