9 stabbings in 5 days — but no, we’re not in the midst of a knife crime epidemic. Here’s why

A recent spate of attacks have the public scared — but what do they tell us about knife crime in the city?

It’s early in the evening when Alan Walsh leaves a crowded pub in Liverpool to make his way home. It’s been a rowdy afternoon; a few pints sunk, a rather heated game of pool— so far, business as usual. Yet as he emerged onto Edge Lane on that fateful day in 1997, something felt wrong. Before he could look over his shoulder he felt a heavy blow to his side. Then another. And another. Within minutes he was sprawled out, covered in blood, being hauled into a taxi by a passerby. He’d been stabbed three times.

“It was touch and go whether I’d live or die,” he tells me, explaining that to this day, he still has no idea why he was the victim of such a violent assault. Knife attacks were rare those days, he says. “There was no need to stab me, I didn’t have weapons. I’d like to meet them and just ask them, why?”

It’s now been 26 years since Alan was viciously stabbed, but looking at recent headlines, it seems knife crime in this city has got worse. This month, nine people were stabbed in just five days across Liverpool, with one victim stabbed in the head at home. Another was stabbed several times in their chest and back; another had their arms slashed.

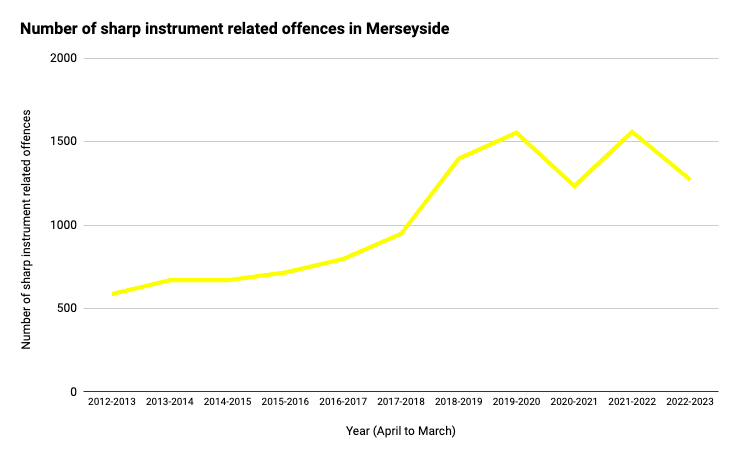

But headlines are just that — headlines. Do the statistics show us that knife crime has rocketed? A total of 1,274 sharp instrument offences were reported in Merseyside between April 2022 and March 2023, marking an 18% decrease on the previous year. Of those, only 6% involved a knife, with other items like glass and scissors included in the count. The figures — while high in comparison to the 587 offences reported in 2012-2013 — show us a promising improvement on the ten-year high of 1,555 offences recorded just before the pandemic.

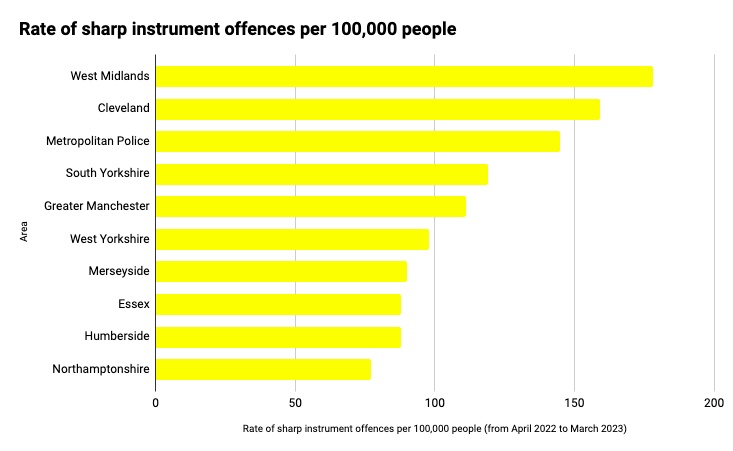

When compared to the rest of the north, Merseyside ranks below Greater Manchester, South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire for sharp instrument offences. In fact, it is as far down as seventh on the list of regions in the UK with the highest knife crime rates, with the West Midlands topping the leaderboard alongside Cleveland. So what does this recent spike in stabbings actually tell us? Should we be worried?

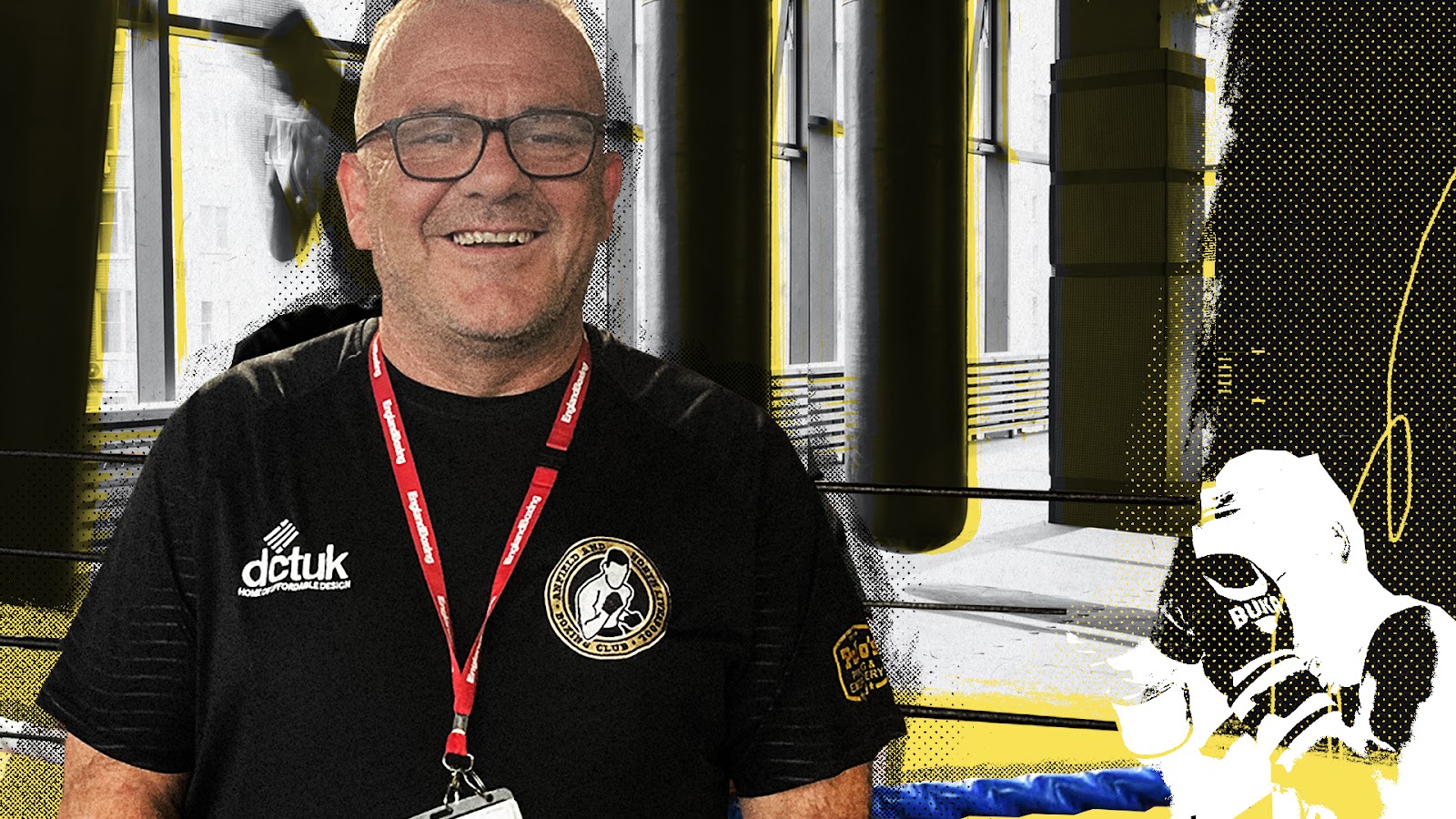

“The big fear really is that stabbings don’t shock anyone anymore,” Alan tells me. He’s now a youth worker and a coach at Anfield Boxing Club, working alongside both victims and perpetrators of knife crime, and deterring others from a violent lifestyle. Most of the children he works with are between 10 and 18 years old, but he tells me he’s seen children as young as eight involved in violence and gang culture.

Alan tells me that one of the most alarming trends he’s seen on the ground recently is how quickly young people resort to using weapons. “We’re seeing — in my experience — more and more suffer fatalities or near fatalities,” he says. “We’re seeing more stabbings in the body part; they’re not going for the arms and legs, they’re going for the body. That’s a really scary thing that we’ve seen.” He explains that for a lot of kids, they carry knives to protect themselves on the false pretence that everyone else around them does. “That’s one of the big messages I’m trying to send,” he adds. “They think everyone is carrying a knife but no they’re not, they need to leave the knives at home.”

So is it mainly young people taking weapons onto the streets? Robert Hesketh, a criminal justice lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University, confirms that young people are disproportionately affected by knife crime — citing the easy access to makeshift weapons as a cause for concern. “Just look around your house, it’s as simple as that,” he says. “Pens, pencils, a simple toothbrush can be sharpened to a shank.” He tells me that usually stabbings occur between people who know each other, often based on an argument that has spilled into violence. “It can be a whole host of reasons though,” he adds, referencing the cost of living crisis as a contributing factor. “Desperate times call for desperate measures and obviously within that there will be higher levels of violence.” He notes that when times are tough, some young people turn to selling drugs to make ends meet, and will choose to carry a weapon as a means of protecting themselves from precarious situations. In an article he wrote for North West Bylines, Robert stated:

“It is of no surprise to see young people resorting to crime and in many instances, violent crime in groups… My research has picked-up observations of parents having been offered money to pay Sky bills in return for their children being used as drug mules.”

Between April 2021 and March 2022, there were a total of 696 murders in England and Wales — an increase of 23% on the previous year. 69 of those killed were aged between 13 and 19 years old, and of those murders, around 75% were killed with a knife or sharp instrument. This provides a stark contrast to the overall knife-related homicide figure — which stands at just 41% of all murders.

It’s clear here that young people are the most likely to be affected by knife crime, but what drives people to carry weapons in the first place? According to Iain Brennan, a criminologist at the University of Hull, one of the main reasons people carry knives is to regain some control over their environment. He explains that an unpredictable home or violent neighbourhood can influence a person to arm themselves.

In criminology, he tells me, there’s a concept called “the social contract”. “It means we give up some of our freedom in order for the state to protect us,” he says. “But if you live in an environment where there's so much violence that the police can't be there to protect you all the time, there's a reasonable expectation that someone might feel the need to carry a knife.”

It’s hard to say if this is the case in Merseyside. While the region by no means has the highest crime rate in the UK (Cleveland, West Yorkshire and Greater Manchester all enjoy the questionable honour of ranking above us on this), Merseyside does have a tough history of gang culture poisoning its waters. Well-publicised cases — take Olivia Pratt-Korbel, Elle Edwards and Rhys Jones — can, at times, make Merseyside feel like the crime epicentre of the country. But the statistics don’t show that, and plus, these were all gun-related killings. So why the desire to carry a knife for protection?

“Where it gets interesting is actually the perception that everyone else is carrying [knives],” Iain says. “We find that the young people who carry them start to believe that everybody else is carrying them, and there’s a sort of reinforcing loop we’ve seen in some studies.”

I ask him how many people actually carry knives. “Generally people overestimate how common these things are,” he explains. According to Iain, only 2-4% of people in the UK report having carried a weapon in the past year — with this figure including people that have carried a weapon just once in the last 12 months. "It’s a very rare behaviour,” he says. He also tells me that while a recent spate of stabbings in Liverpool may seem alarming, it's actually the same pattern UK-wide every year. “The peak months for serious violence is June to August,” he says, adding that this time frame roughly coincides with the school holidays and people spending more time outside. “So I really wouldn’t say the sky is falling in or there’s anything really unusual happening.”

Despite this, Iain still believes more needs to be done to tackle knife crime, citing the unpredictable nature of knives as a key factor in their danger. “Most people, when they’re in a fight, they’re not making good and rational decisions,” he says, noting that situations with weapons can rapidly get out of hand, leading to levels of violence that are out of character for the people involved. “When adrenaline is flowing, it doesn’t make things very clear,” he says. “Introducing a weapon into that situation really just puts everybody at significantly greater risk.”

While the studies and statistics suggest a knife crime epidemic isn’t on the horizon, this does little to absolve the consequences of using a weapon. One person who has witnessed the devastation caused by knives firsthand is Dr Nikhil Misra, a Liverpool trauma surgeon and founder of Knifesavers — an initiative that teaches the public how to deal with knife wounds and blood loss.

Dr Misra founded Knifesavers back in 2018, after he was unable to save the life of a young man that had been stabbed. The death came during an intense summer of knife crime in Merseyside, with sharp instrument offences rocketing by 48% on the previous year. The death deeply affected him and his colleagues, who had already seen another person die from a knife injury during that period. “It was a career defining moment for me,” he says. “It just broke me. It was one of those moments where I stopped and said, I can’t keep doing this.”

Now, Knifesavers — which he runs in his free time — hosts workshops and events across Liverpool to teach the public how to deal with knife wounds. Training courses using bleeding control packs educate the public on blood loss prevention: a practice that is vital in the time it can take for an ambulance to arrive. He explains that the average wait time for an ambulance in a stabbing case is between seven and eight minutes, yet it takes as little as five minutes for a person to go into cardiac arrest from blood loss. “We want Knifesavers to fill that gap,” he tells me. “We want this knowledge for bleeding control out there, for people to know what to do.”

I ask him what the biggest misconception about stab wounds is. “The danger of a single knife wound,” he says. “I strongly believe that isn’t recognised.” He tells me that he often gets asked in training courses if it is possible to die from a single wound, or die from an injury that isn’t on your torso. “Anywhere can be a wound, and any wound can bleed,” he tells me, adding that he’s seen people die from injuries sustained by a single stab wound to the arm or leg.

It’s obviously an asset for this city to have skilled doctors like Dr Misra working here so that, if the worst case scenario happens, the victim stands a chance of surviving. But what if the stabbing never happened in the first place? On thinking about Dr Misra’s medical work, it seems logical that if health care can be both curative (like taking medicine) and preventive (like getting a vaccine to stave off an illness in the first place), so too can approaches to tackling knife crime. I want to speak to Alan, the youth coach at Anfield Boxing Club, to find out more about taking a preventive approach. Is it possible to predispose young people to never want to pick up a knife in the first place?

His boxing club is tucked away on Queens Drive. It’s small, with faded posters of fighting heroes lining the walls and sports shorts draped over the bannisters. I follow the sound of shouting and jeering upstairs, expecting to see gaggles of teenage boys, faces obscured by mouthguards and helmets. Yet as I walk through the doorway I see a girl, no older than 12, kitted out in the ring.

“Go on!” the kids around her shout. She’s boxing a boy about her own age, and although I’ve only been here a few minutes, it’s clear she’s winning. “She has a lot of promise,” Mark tells me — he’s been a coach here for over a decade, and was once a boxer himself. The bell rings, and the girl walks out from the ring looking victorious, the boy she’s just pummelled traipsing behind her. I ask Mark if they often let the boys fight against the girls — in most sports they’re split up. “If you’re a boxer, then you’re a boxer,” he says. There’s none of that nonsense here.

Alan comes over to greet me, explaining that I’ve arrived slap bang in the middle of a rather busy coaching session. “We’re probably the number one project that young people come to when they’ve got involved with gang culture and violence,” he says. He tells me that on top of the club, he works with around 20 schools across the city as part of his Real Men Don’t Carry Knives initiative, educating children, parents and teachers on violence reduction. “We’re actually about to become the first boxing club in the country to become a trauma informed education centre,” he adds proudly.

I ask him what he thinks needs to be done to tackle the issue of knife crime in Liverpool. “We've got to empower young people to make that change,” he says, explaining that through the boxing club, children are given a purpose paired with plenty of opportunities to get their energy and angst out. “We’ve got to buck the trend, and young people have got to start telling other young people that you know what, let's put the blades away,” he adds. “We need to instil in young people that life is precious, because a lot of them don’t see the value in life.”

Despite the nature of boxing, there is no violence in this room. There’s boundaries, respect and good sportsmanship; all qualities that should serve each participant here in their adult life. I see teenage boys high-fiving eight-year-olds, giving them tips on their boxing stance. I see 21-year-old Drew laughing along with his trainer of ten years. This boxing club, along with the vital work of charities like Knifesavers, offer hope for the elimination of knife crime; through changing the way we think about weapons and violence, and changing the way young people think about themselves. “It’s all about visualisation,” Alan tells me. “If all they’re seeing is deprivation, antisocial behaviour, a lack of aspiration — we need to instil some hope back into these young people.”

But what about those that have already committed their first offence? Robert Hesketh, the psychologist from Liverpool John Moores University, tells me it’s all about “changing the culture” to stop people returning to violence. “It’s not going to be done overnight,” he says. “Because what you're talking about is changing beliefs, ideas, norms, all of that stuff. And you can only do that by changing the environment.” He explains that increased police presence in crime hotspots can help limit the amount of weapons in an area, leading to less of a perceived need to carry a knife for protection.

For now, both prevention and rehabilitation remain vital for the steady erasure of knife crime in our region. After years in the making, Knifesavers is set to launch its bleed kit boxes across Liverpool by the end of 2023 — similar to the defibrillator boxes that have been dotted across city centres for years. The new resource should allow more members of the public to intervene in an emergency and save lives, but Dr Misra tells me it’s the changing of people’s hearts and minds he is really intent on. “It's a crusade to change the perceptions of young people in the city,” he says, noting that Knifesavers’s workshops and presentations across Liverpool are what will make the biggest difference in prevention. “The growing importance now is getting that idea in the front of people’s heads, that there’s no such thing as just a single knife wound,” he tells me. “We need that societal change.”

Comments

Latest

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

Losing local radio — and my mum

And the winner is...

9 stabbings in 5 days — but no, we’re not in the midst of a knife crime epidemic. Here’s why

A recent spate of attacks have the public scared — but what do they tell us about knife crime in the city?