Manchester: Liverpool’s greatest creation

How the brightest lights of Merseyside made their Mancunian nemesis

Today’s free-to-read article concerns the Liverpool-born talent that helped revolutionise Manchester, whether in music, comedy, architecture, politics or sport. What drew them inland? Was it a desire for space, a need for infrastructure, a thirst for knowledge?

In your own quest to know more, you might consider that The Liverpool Post is this city’s only quality newspaper capable of delivering cultural pieces, deep dives and breaking news. Why not take advantage of our introductory offer and receive our full catalogue for just £1 a week?

Signing up today will help keep our reader-funded project thriving for the whole city region.

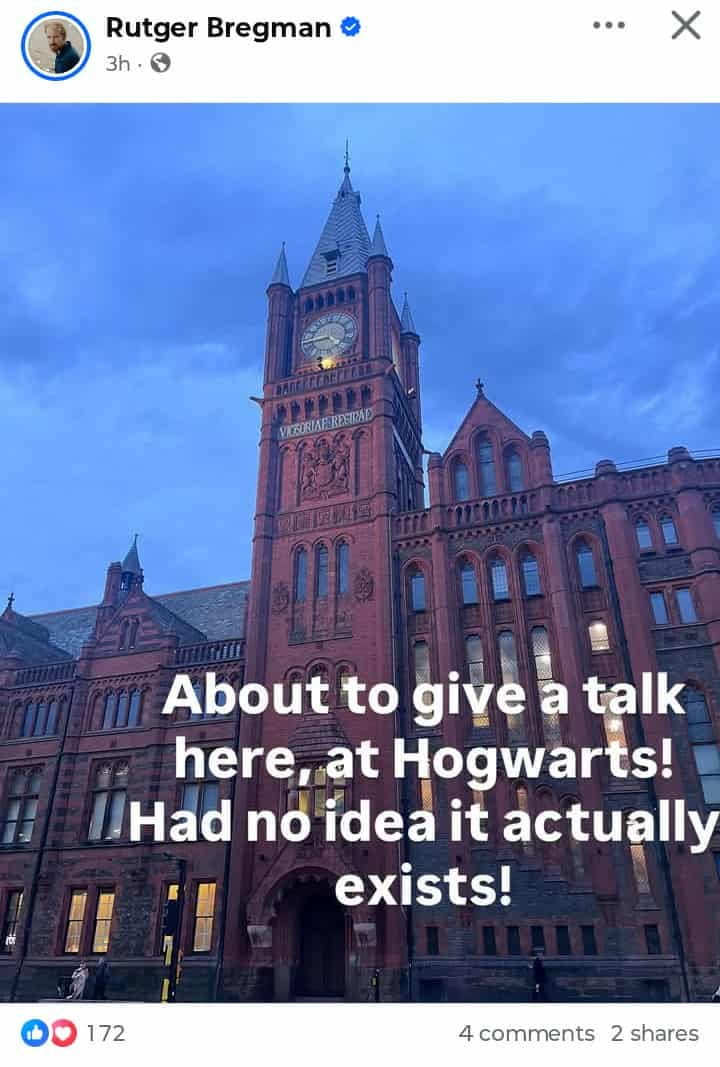

So there I am, on Brownlow Hill, when a stranger hands me the rare opportunity to sound clever. “This building is fantastic, isn’t it?” she says, after asking about my press pass.

We’re queuing outside the Victoria Gallery and Museum. In an hour, historian Rutger Bregman will deliver a BBC Reith Lecture on the necessity for moral revolution. Dusk descends on the building’s moody Venetian red exterior, darkening its deep intercostal grooves until the whole structure resembles some ornate torso of stone beef. I shake myself out of an embarrassing campus memory — in my day, the Victoria Building was the registration office for Liverpool University — and answer with a confidence that startles even me:

“Yes, a fine example of the Gothic Revival. Alfred Waterhouse, if I’m not mistaken. And the original ‘redbrick’ university building, from which the term is derived.”

Unbeknownst to my fellow conversationalist, who has travelled up from Surrey to hear Bregman speak, this is just a half-remembered fact from an earlier article about our city’s undervalued Gothic buildings: I don’t, as a rule, sound like Roger Scruton on a bad day. But as we enter and join the queue for the cafe — named for the building’s architect — I begin to brood on the fact that Waterhouse did most of his best work in London, Cambridge and, of course, Manchester.

It’s true: the Liverpool-born, Aigburth-raised Alfred Waterhouse, who designed the Royal Liverpool Infirmary, Lime Street’s French-palatial North Western Hotel and the Prudential Buildings on Dale Street, is better known for his major contributions to Manchester’s architectural heritage, including the Town Hall, the Museum, Strangeways prison, Owens College (the precursor to the University) and the Assize Courts (sadly destroyed in the Manchester Blitz).

I’m actually one of the few people who likes both Liverpool and Manchester. Back when I’d begun to find the coastal city’s nightlife rather sedate, my first teenage ventures to Manny opened up a dizzying world of sybarite opportunity. Even these days on my way home from meetings at the Mill Media office I get the tantalising sense that, if I just stayed an hour longer, anything could happen. I could never live there, but that’s because I have salt water in my blood — wherever I am, I seem to orient myself by the river or coast, for which canals are a poor substitute — not because I have anything against Manchester or its fine people.

And yet, taking my seat in the lecture theatre upstairs in the Victoria Building, I suddenly feel like I’m 16 years old again, watching my hero Wayne Rooney sign for Manchester United. Bregman’s lecture doesn’t help: he talks about how abolitionist Thomas Clarkson was welcomed in Manchester in 1787 after having been attacked and almost thrown in the Mersey in pro-slavery Liverpool, which went on to back the Confederacy in the American Civil War.

With a ludicrous, petulant defensiveness, I begin to think of other Liverpudlians who travelled inland and became legends. By the time Bregman is soaking up the applause, I have a mental list: Caroline Aherne, who redefined Manchester’s comedy scene, first studied drama at Liverpool Polytechnic; DJ Greg Wilson, who shaped “Madchester” was from my home town of New Brighton; even current mayor Andy Burnham, who recently called his political philosophy “Manchesterism”, is an Everton fan from Old Roan.

Why, ever since the Ship Canal — built by Mancunians to bypass the hegemony of the Port of Liverpool — Manchester’s been siphoning off the great and the good of Merseyside! Why does this keep happening? Over the next few days, I spent inordinate amounts of time in the library, speaking to people and looking through my own notes to discover how it came to pass that Liverpudlians helped create their own rival city.

In Waterhouse’s case, it’s because there were just more opportunities in Manchester. Its 19th century building boom coincided with Waterhouse’s professional blossoming, while Liverpool’s architectural style was better established. Manchester went from being the “greatest mere village in England”, as Daniel Dafoe had described it in the 1720s, to the first truly industrialised world city, as illustrated by its population growth: from 10,000 in 1700 to 400,000 at the start of the 1850s. In 1854 the prolific Waterhouse, fresh from his “Grand Tour” of Europe, heady with Rayonnant cathedrals and Italian monasteries and enamoured of John Ruskin’s Gothicist ideas, set up in Cross Street Chambers and went about putting his hero’s ethos into masonry.

“Of the two great Northwestern cities,” Peter de Figueiredo, architectural historian, told me, “Manchester tended to go for Gothic buildings while Liverpool favoured the Classical,” meaning that the Venetian Gothic style of Waterhouse’s Assize Court or the ribbed vaults of his Town Hall helped make Manchester a fashionable Neo-Gothic metropolis, while Liverpool remained staidly Neoclassical. The Kimpton Clocktower Hotel, begun by Alfred Waterhouse and crucial for Oxford Road’s aesthetic, was extended by his son Paul, who also built Whitworth Hall. Manchester Museum, originally Alfred’s design, was also extended by Paul and completed by Paul’s son Michael Waterhouse, the later additions connecting it with the Whitworth building to complete Oxford Road’s Gothic cornucopia.

But what about more recent times? Since its decline as a major shipping hub, perhaps Liverpool’s greatest export was music. I need not once again belabour The Beatles’ influence: as music promoter Marc Jones told me in a Bold Street caf recently, they were simply bigger and more famous than any single Manchester band. The Fab Four played the ABC Cinema (now the Apollo) in November 1963 and sold LPs by the ton.

They left a legacy, too: The Smiths’ Johnny Marr has said Revolver and Rubber Soul made him want to pick up a guitar; for The Stone Roses’ Ian Brown, “everything starts with” John Lennon; and Noel Gallagher once remarked that “Without The Beatles, there would have been no Oasis.” Even Peter Hook, whose work with Joy Division could be described as a repudiation of the Liverpudlians’ poptimism, confessed The Beatles were the first band he was ever aware of.

But Manchester impresario Tony Wilson, in one of his last pieces of writing before he died, said that Liverpool’s docks themselves were still the entry point for what followed down the A580:

“[Liverpool] had become the centre of the world”, Wilson wrote for Mersey: The River That Changed The World, acknowledging its port as “central to this great spark of creativity” and creating a 1950s “culture of R&B aficionados” that fed into the “fresh vibrant youth culture based on the music of black America” in 1960s Liverpool. Those same docks that had grown fat on black lives became a conduit for blues rhythms, allowing Manchester and the rest of the country access.

Whether you're joining us from Merseyside, Manchester or further afield, you're more than welcome here. In fact, why not sign up for free today and get all non-paywalled editions into your inbox? That includes briefings, big stories and even features like this one. Click below to find out more.

“This is Manchester: we do things differently here,” as Wilson famously said. It’s become a wildly popular slogan for the city, featuring on everything from posters to promotional material to tea towels. Except, of course, Wilson never said that: Steve Coogan, playing Wilson in 24 Hour Party People, did. And who wrote the line? Liverpool’s own Frank Cottrell Boyce.

Wilson’s seldom acknowledged precursor as a promotional force in the North West was Roger Eagle. Here’s an anecdote: when obscure punk band the Frantic Elevators split, their singer spent weeks in Liverpool absorbing that same Afro-American sound from Eagle’s record collection — that singer was none other than Mick Hucknall, the Mancunian who would later bring that musical education and vocal style to bear with Simply Red.

But Eagle’s influence did not end there. By co-founding Eric’s Club and putting on The Buzzcocks, The Sex Pistols and The Slits, as well as providing a launching pad for local legends like Echo & the Bunnymen, the Teardrop Explodes and OMD, Eagle arguably proved that North West punk was a viable scene. This was years before Wilson signed Joy Division to Factory Records or opened the Haçienda. And in the early 80s, Eagle — who’d cut his promotional teeth as a booker for the Liverpool Stadium, himself made the by now familiar trek inland and set up his own Manchester venue, The International, which gave The Stone Roses (among others) some of their earliest gigs.

Of course, this is perhaps where my argument that Manchester is a Liverpool creation begins to fray at the edges. Roger Eagle was in fact born in Oxford. And his first motorcycle-enabled trips up north were to Manchester: in 1965, over a decade before Eric’s, Eagle worked as a DJ at the Twisted Wheel, first on Brazenose Street and then Whitworth Street — incidentally, where Wilson would later found The Haçienda.

Likewise, Andy Burnham’s purely Scouse credentials are also somewhat suspect. The current mayor spent most of his childhood in Manchester rather than Liverpool: dropped off at the Arndale or Lancashire Cricket Club for the day while his dad worked in the Post Office. In a recent New Statesman interview, Burnham (perhaps diplomatically) says he is “both” a “Scouse bastard” and a “Manc bastard”, as Man City and Everton fans respectively chanted at him.

And although, yes, Caroline Aherne learned her dramatic trade in Liverpool, she was born in Ealing to Irish parents and brought up in Wythenshawe. Damn.

Even my beloved Waterhouse is of ambiguous origin. It’s doubtful that the eclectic Victorian, his father a prosperous Quaker from Tottenham, would have had any notion of a Liverpudlian conscience — certainly not a Scouse one. According to historian Keith Daniel Roberts, a shared identity did not occur until the city’s sectarian battles diminished. Other elements we associate with Liverpool’s soul — sporting success, left-wing politics, humour, anti-establishment sentiment — are also relatively recent, 20th century developments. By that time, a Mancunian ethos had long been in evidence: the Peterloo Massacre, laissez-faire economic theory and radical politics had all formed the city’s temper in the previous century. Waterhouse, who learned his architectural trade in Manchester and plied it there for 11 years, may have come to feel Lancastrian at most.

One figure there can be no doubt about is Wayne Rooney. The Croxteth-born talisman still speaks with a Scouse accent, leaving some Manchester United fans uneasy about his status as their club’s greatest ever player. “He’s got, what, 250-odd goals and 13 trophies?” James, a lifelong United supporter of my acquaintance, tells me. (It’s actually 253 goals — more than any other in the club’s proud history.) “You’ve got to put him [on top]. But not everyone’s happy about it.” Least of all me. I still regard that 2004 move, burnt into my soul like caustic soda, as a betrayal.

And yet, the thought of the Manchester/Liverpool football rivalry reminds me that there was, after all, once a shared Lancashire identity, until the nebulous creation of “Merseyside” and “Greater Manchester” in the 1970s. On YouTube, there’s a clip of Everton’s Dixie Dean and Manchester City’s Sam Cowan toasting to Lancashire, each man hoping that if his club can’t win the FA Cup, the other’s can.

When I announced the genesis of this article on Monday, I was in something of a provocative mood. The contributions from readers made me more conciliatory. I’m delighted to receive, for instance, an email from Dougal Paver, hoping that I will not revive the “old canard” about the Manchester Ship Canal initiating the long-term decline of the Liverpool Docks. (Sorry, Dougal.) To prove his point, he cites his own mother-in-law, University of Liverpool lecturer Arline Wilson. She “always maintained that the data showed otherwise: there was no impact on Liverpool’s traditional markets because the ship canal opened up opportunities hitherto un-served by Liverpool,” naming chemical, food and other new processing industries, while Liverpool continued its historic domination of the cotton trade.

Less positive is a communication from Jack Stopforth, former CEO Liverpool Chamber of Commerce and ex Chief Economic Adviser for Merseyside County Council, who tells me his “heart sank” upon reading my intention to drag up the Liverpool-Manchester rivalry. Stopforth does not see this relationship as a zero-sum game, but increasingly an opportunity for “overall regional prosperity.”

Certainly, this is something that Burnham and Liverpool’s metro mayor Steve Rotheram promote. Whenever they’re together, that is: Burnham less so when he’s on his own. A bitter pill for Liverpudlians is that, football aside, we don’t feature anywhere near as prominently in the Mancunian imagination as they do in ours. This is because, just like in the 19th century, Manchester is the fastest-growing city in the UK and Liverpool… well, isn’t.

But that’s not to say Merseyside doesn’t have so much to offer, as so many of the case studies above show. And I see Jack Stopforth’s point: after all, there’s maybe nothing that’s more severely undermined a sense of Northern solidarity than aimless squabbling between Scousers and Mancs over who’s got the best bands or most skilful sportsmen.

Indeed, perhaps all the above shows is the healthy cross-pollination between the two cities — pointing, as David Lloyd has argued in these pages, towards the need for “a real alliance” between Liverpool and Manchester, “instead of tinkering around the edges and increasingly futile HS2-manifesting.”

Call such an alliance what you will. Mr Lloyd tentatively suggests “Liverchester” over “Mancpool”, while Burnham and Rotheram (“Burnerham”?) like the “Northern Arc.” I happen to enjoy “Lanc-Futurism” as a general ethos. But although all this would be congruent with a proud — and shared — tradition, barely concealed within these pitches for joint projects is that same fetishisation of growth at all costs that poisoned the Mersey and left Manchester with chronic overcrowding, awful sanitation, several public health crises, and stark social inequality by the end of its Industrial boom.

What I'm talking about is more artistic collaboration that prioritises the work itself. Waterhouse built after Neo-Gothic, Jacobethan and or Italianite styles not because he was some arch reactionary but because he understood that, whether you were in a Northern cottonopolis or an Oxbridge college, a sense of beauty, grandeur or fine detail fires the imagination and spurs civic pride. Paradoxically, that commitment to artistic integrity is when the city (or cities) most benefit.

The role of politicians and town planners is to facilitate that wherever possible and get out of the way. By the time Waterhouse set up his Manchester practice, the Liverpool-Manchester Railway – the first innercity track of its kind — had been running for almost a quarter century. When Roger Eagle and Tony Wilson were knocking around, the cost of train fare meant their respective cities were closer: even when I was popping to Oxford Road for the weekend, the ticket cost about £3.50. Now it's more like £20 return.

The good news (if its not a vanity project) is that Burnerham do want a new Liverpool-Manchester Railway to facilitate a (shudder) "growth corridor." Fine. But no matter what schemes metro mayors or economic planners dream up, it's the cultural marriage across historic Lancashire should be encouraged to blossom once more.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

Thanks for reading today's edition of The Post. If you liked what you read, why not sign up for free today and get all non-paywalled editions into your inbox? That includes briefings, big stories and even features like this one.

Comments

Latest

Just what is happening with Peak Cluster’s CO₂ pipeline?

A ‘stitch up’? How Wirral council bungled Big Heritage

Merseyside’s buses are coming back into public hands. Why not trains too?

From Jimmy McGovern to Len McCluskey: The household names rallying behind Writing On The Wall’s employees

Manchester: Liverpool’s greatest creation

How the brightest lights of Merseyside made their Mancunian nemesis