Liverpool's cookie-cutter new buildings are soulless. Who's to blame?

David Lloyd on how we must end our toxic relationship — with cladding

Liverpool Art Fair returns

From today’s sponsor: Liverpool Art Fair returns for its 11th year of celebrating and showcasing the work of local artists. Head down to the Royal Liver Building to see the showcase of over 200 artists from 11th July to 25th August. The Fair prides itself on offering art for every budget, with work starting at just £20 and all pieces under £2000. It continues to bring together local artists with art buyers, supporting creative careers. Alongside the Fair, workshops are being run all summer to encourage visitors to tune into their own artistic side. Admission is free and everyone is encouraged!

There was a time when city tour guides encouraged you to look up. Liverpool's finials and cupolas, our pediments and cornices and its intricate stonework singled our city out as a place that was well put together. A city of innovation and craftsmanship. A city that thought about how its built environment was a statement of civic pride.

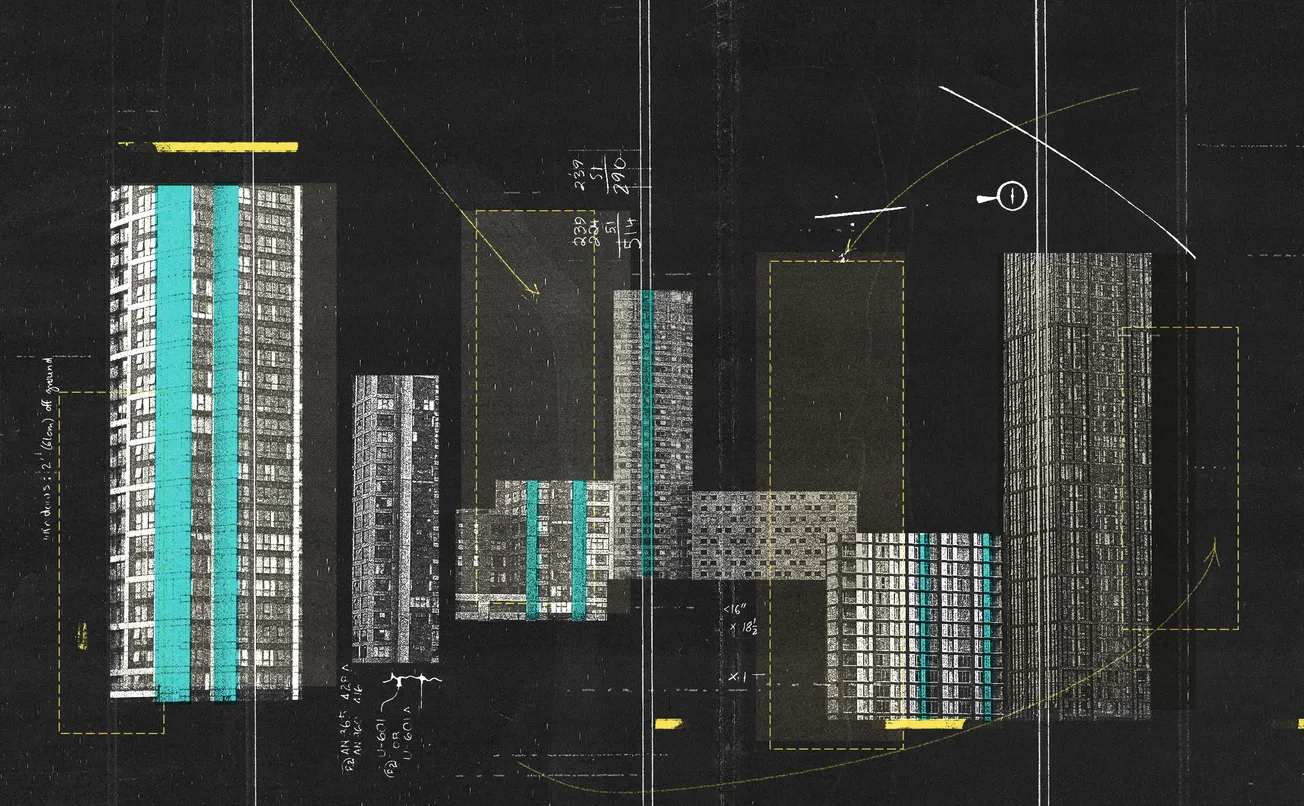

Along Water, Dale and Castle Streets, it's still worth getting a crick in your neck to spot the terracotta tiles and mosaics of the British and Foreign Marine Insurance Company Building, or the flamboyantly Gothic traceries of the State Insurance Building. But, increasingly, any scan of our skyline comes with a sudden, jarring, pixelated glitch. A barcode where there should be a building. London Road, Islington, Duke Street and the Ropewalks are prime hunting grounds, but these boxy any-town interlopers have taken up residence across all corners of the city. Liverpool’s new buildings are being shrink-wrapped in crap cladding.

Last week’s news that the city is considering a new planning framework to protect our built environment came with a special audio track. It was the sound of our council attempting to shut the stable door long after the beast had bolted. “This will help us protect our cherished landmarks while making new ones. This city belongs to its people, which is why consultations with residents and businesses are so valuable,” Councillor Nick Small, Cabinet Member for Growth and Economy said.

Lofty words, Nick. But, I’m curious, what do you make of the twenty years’ worth of dross that’s sprouted up alongside our ‘cherished landmarks’ from St George’s Hall to our historic docks, since you’ve been a councillor?

Our city, like every other city from here to Seattle, has surrendered to the tyranny of this cheap aluminium cladding. You know the sort of building I'm talking about. A shipping container given a glow up by a firm of accountants. A Dazzle Ship that has slipped free of its moorings and wedged itself, rudely, into our streetscape. And much like those cunning WWII vessels, the contrasting Jenga stripes and geometric patterns are designed to confuse and bamboozle us. Instead of "I see no ships," the theory is that these curtain walls of cladding are supposed to make us not see the mediocrity in our midst.

So how did we get here? And is it our fault? Well, maybe…but more on that later.

The Cladding Revolution

At the beginning of the 21st century it was pretty obvious that something awful was happening to our built environment. Aluminium composite cladding (two thin aluminium sheets bonded to a non-aluminium core) broke free of its patent restrictions, making it much cheaper to use. Important new developments that were once the sole domain of professionals, architects and time-served craftsmen were being churned out by developers' own in-house CAD (computer aided design) teams, and these tatty Tetris blocks were all skinned with this cheap ACM cladding – fatally, in the case of Grenfell, with its highly combustible polyethylene core. Cue remedial work around the city, as 'luxury' apartment blocks from Cheapside to The Strand were hastily retrofitted with cladding that wasn't, effectively, tucking residents up at night in a cling film-like layer of highly combustible fuel.

But this isn't a feature about that. This is a feature about how ACM cladding promised us a brilliant new future. A dazzling skyline of durable, appealing and affordable city centre living. Twenty five years later, that future is here. Architects are out, and so-called 'value engineering' is in.

Anyone who can punch in a plot size, crunch the data and prime the algorithm to extract maximum bang for the developers' buck can design a flagship new apartment block in minutes. An apartment block like, say, Iconic on the once-handsome Renshaw Street (which is about as iconic as ten thousands spoons), or Faulkner Chester Hall's vapid and remedial work-ridden Circle 109 in Chinatown.

There was a time, too, when you could tell a city by the stone it was hewn from: Aberdeen's silvery granite that glistens in the North Sea haar, or the honeyed hug of Bath's Royal Crescent. Liverpool, too, with its red Woolton Quarry sandstone and the Portland Stone of its three graces, has its own distinctive signature.

These are, sadly, buildings of an altogether distant geological epoch. An epoch when, ironically enough, Liverpool's architectural innovations led the world. And that's where our story takes a cruel twist.

The Birthplace of Modern Cladding

Crap cladding is only possible thanks to a pivotal shift in the way we imagined our buildings. A shift that occurred, as it happens, right on our doorstep. Stand on the corner of Water Street, looking down the length of Covent Garden and you're witnessing the birth and death of cladding's great promise.

To your left, Peter Ellis's Oriel Chambers (1864) is considered to be the world's first example of cladding. A metal-framed core holds the structure up, while slivers of sandstone mullions and glass curtain walls adorn its facade. It still looks magnificent after 161 years. At the end of Covent Garden, over on Chapel Street, Unity Building's defective cladding was replaced in 2015, just eight years after the building was completed.

So how, and why did we fall so far?

This article was published by The Post. If you want more stories like this delivered directly to you via email, you can sign up to our free mailing list using the button below.

Liverpool's pioneering iron and steel-framed buildings gave architects freedom to make merry with non-load-bearing exterior walls. Suddenly, facades could be a canvas for their creativity. Walls could be windows. They could be sinuous stone sculptures, shimmering slices of porcelain, gleaming mosaics… or shit-splattered aluminium cladding.

Ellis's Oriel Chambers let the light flood in, in so many ways. Architects could leave the heavy lifting to the building's hidden frame, allowing the façade to be more about aesthetics than mere structural necessity. The world might have been slow to catch on, but Liverpool took it and ran with it: 16 Cook Street (1866), also designed by Peter Ellis, extensively used glass in its facades two years later.

Both buildings influenced the Chicago School of Architecture – and the city's transformative skyscrapers – with John Root (who would become a leading American architect) studying in Liverpool at the time of their construction. You can trace a line directly from Water Street to every skyscraper across the globe. And we didn't stop innovating. Tower Building (1910, Walter Aubrey Thomas) is one of the first-ever steel-framed buildings. Today, after a recent buff and polish, its glazed terracotta cladding looks like a glorious fondant fancy in some upscale French patisserie's window. This after 115 years facing the elements along the waterfront.

I wonder how well the cladding on nearby Travelodge will look in a century's time (clue: it's looking tired already)? Or, for that matter, how many times will the scaffolding be re-erected around Beetham Plaza to fix its contentious cladding?

Then there’s an apartment block halfway up Islington, called Falkland House, that looks like a decaying barracks in a long-abandoned Siberian mining town. It was built less than 15 years ago — within the UNESCO World Heritage buffer zone. The shock isn’t that we lost UNESCO. The shock is that they patiently waited for six more years after this.

The Developer's Dilemma

This disconnect between our historical architectural ambition and our contemporary development practices hasn't gone unnoticed. Dave Brewitt is the owner of Hope Street Hotel and Joint Managing Director of Carpenter Investments, whose property portfolio, while diverse, has one striking thing in common: real bricks.

"If a salesman comes to our architects to say I've got this really cool cladding, I’d want to know how it weathers, especially in a city as open to the elements as Liverpool. What patina will it develop in ten, twenty or fifty years’ time? The first question should always be: how can cladding make this building better, not how can it cut corners with cost.”

Making a building look cool with cladding isn't, Dave says, impossible. In fact, it's given the world the likes of Frank Gehry's shimmering confections, or Zaha Hadid's organic masterpieces. “Look at the stainless steel cladding of New York’s Chrysler Building or the limestone, granite and brick cladding of the Empire State,” Dave says. “Cladding isn’t the problem. Quality, durability and aesthetics are what matters.”

Not that every new building needs to be an object lesson in jaw-dropping starchitecture. Even here, there are good examples of how cladding can look considered, confident and even cool. Take a look at Copper House on the Strand (Leach Rhodes Walker). The detailing – such as the windows' gleaming white stone cladding not being flush with the elevation – adds depth and interest to the façade, distinguishing it from the flat, less considered appearance of the rest of our city's cheaply clad buildings. The Jura beige limestone of the Museum of Liverpool (3XN & Buro Happold) with its geometric facades is a worthy addition to the waterfront. And, talking of waterfronts I'd even suggest Peel's Mariner's Quay in Wallasey, with its jaunty row of Crayola-coloured wharf-style apartment blocks, as another good example of cladding thinking outside the box.

"If materials are reduced down to their lowest cost you end up with something that's just doing a job of wrapping a building to stop the rain getting in," Dave says. "The question is," Dave says, "how do we, as a city, proscribe beauty? Put two architects together and they'll come up with a thousand different formulas.”

Arrange a public consultation, I suggest, and you just multiply that by a room full of experts. I still shiver at the memory of Will Alsop being eviscerated when he came to the University to talk about his ‘fourth grace’ Cloud proposal. Cue a swift exit, and the loss of something genuinely magical in our midst.

The City that Planning Built

“It’s essential that planners encourage creative thinking.” Dave says. "The Portland stone and granite-clad Three Graces could easily have been denied due to various planning regulations around size, context and materiality," Dave says.

Buildings that sail through are the safe, the uniform and the proposals that don't scare anyone. Architecture writer Kriston Capps calls them the ‘fast casual’ buildings. The architectural equivalent of junk food. Harmless enough when sprinkled sparingly, but catastrophic as the bulk of your diet.

“Blocky mixed-use glass buildings are the market’s best answer yet to working under the strict costs and restraints involved with building in cities today,” he says. Which is why most of our city's new builds tend to look like minute variations on a theme, rather than considered and articulate additions to Liverpool's centuries-old architectural conversation.

"It's diversity that makes a city great," Dave says. "Planning guidance often relates to the urban context. But most great buildings are in stark contrast to their surroundings, so it's really difficult to be different. So we've ended up in a situation where the only option for developers is to play it safe to get their building approved."

Our streetscape, Kriston adds, is the direct result of ‘several vexing problems’ that give rise to this abundant fast casualism – this McDonalds morning, noon and night. “Height limits force architects to max out a project’s floor–area ratio and cut short the tops of projects - restrictions that add up to modest Lego blocks.” Think Cesar Pelli’s cruelly truncated One Park West, or the oddly stumpy tower of Mann Island.

There are, of course, some cities with a unified appearance you'd tinker with at your peril – Paris, Vienna, Brussels – but Liverpool's brilliance is its wilful idiosyncrasy. The sudden Latin American flourish of the Metropolitan Cathedral, the Egyptian-inspired tunnel ventilation shafts, or the futuristic thrill of Dale Street’s Midland Bank building speak of a city that’s always played hard and fast with the rules.

At least, it used to. "Each new lacklustre development makes it look like we're a city not worth investing in,” Dave says. “We have to take a different approach. We have to believe in our people, and believe that the value of our built environment is something more than a spreadsheet….

“Attracting high quality developers to our city becomes harder with every poor planning decision.” Dave says.

“Obviously we have to consider economic viability, but what we really need to foster is some positive creativity.”

We have it to spare. That's the thing about Liverpool: we've been here before. We've been the city that others looked to for inspiration, for innovation, for the courage to do things differently. From those revolutionary iron frames that gave birth to the modern skyscraper to the chutzpah of our civic monuments that still have the power to stop us in our tracks today, our city isn’t short of clues to the way forward.

When developers call the shots, we get what we've been getting for the past twenty years. Our buildings are where we rub up against our city. They possess the power to transform our streets and structures into places that command attention and elevate our senses. Mooch around the top end of Duke Street, Copperas Hill or London Road today and you get that strange sense of displacement; as if you’re in a transit lounge. A holding space. A back lot.

Not a real city.

So, yes, maybe it is our fault. We invented modern cladding. But we shouldn’t shrink away from it. We should celebrate it. Now we need to find the courage to shed our skin and start over.

This article was published by The Post. If you want more stories like this delivered directly to you via email, you can sign up to our free mailing list using the button below.

Thanks again to Liverpool Art Fair for sponsoring this edition

Comments

Latest

Is Liverpool resting on its laurels?

From Hoylake to St Helens, community cinema is making a comeback

Millions of tonnes of greenhouse gas to be piped under Liverpool Bay

The unexpected auction: A London fund manager is selling Merseyside homes from under their tenants

Liverpool's cookie-cutter new buildings are soulless. Who's to blame?

David Lloyd on how we must end our toxic relationship — with cladding