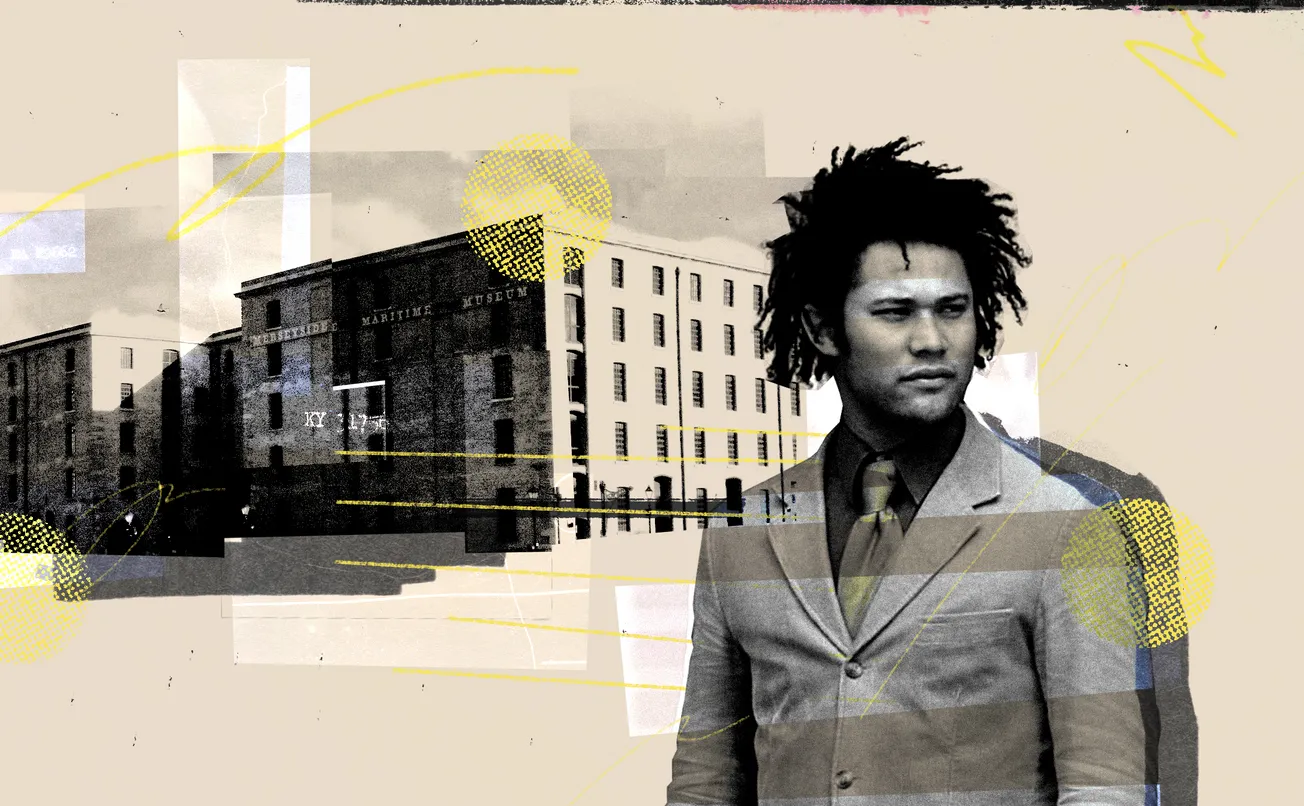

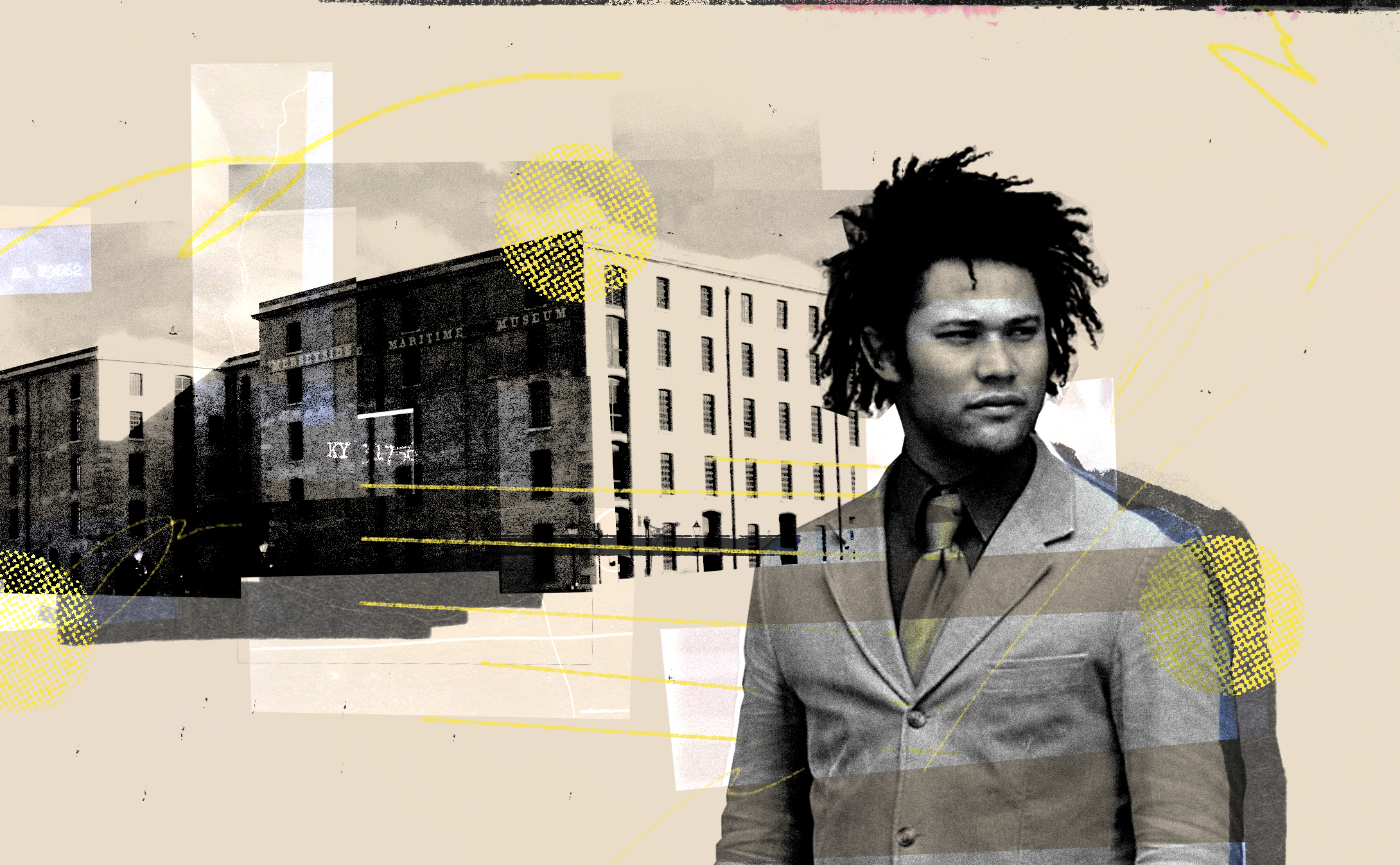

Laurence Westgaph was a known abuser. Why did National Museums Liverpool look the other way?

A Post investigation reveals how the city’s biggest cultural institution ignored allegations of sexual and domestic violence against its resident historian

Editor’s note: This story contains descriptions of sexual and physical violence and coercive control. The names of victims have been changed to protect their anonymity.

Producing this kind of journalism takes months of research, rigorous fact-checking and interviews with vulnerable sources. If you want more stories like this delivered directly to you via email, you can sign up to our mailing list for free using the button below. You’ll be joining 32,000+ readers already on our list, and you'll also be supporting us in our mission to deliver a renaissance in high quality local journalism.

In August 2020, the woman in charge of most of Liverpool’s museums and galleries got a private message on Twitter about a matter that was described as “sensitive and pressing”. As a senior executive at National Museums Liverpool (NML), Janet Dugdale was one of the most influential figures in the city, in charge of over a million objects and artworks across eight sites, including the Walker Art Gallery and the International Slavery Museum. And she had just made a decision that was proving to be immediately controversial.

The message concerned NML’s appointment of a Historian in Residence — not usually something that would attract much public interest. This was the summer of global anger over the killing of George Floyd and the subsequent protests over racism and police violence. By appointing a local black historian called Laurence Westgaph, NML was taking “an important action to help us achieve our promise to be anti-racist,” Dugdale was quoted saying in a press release.

But the message that dropped into Dugdale’s inbox told a different story about Westgaph, calling him “a perpetrator of sexual and domestic violence” and describing his appointment as “an affront to both victims and survivors.” Dugdale replied to the message, promising that she would get back to the writer. But she never did, and Dugdale has chosen not to answer our questions about why.

NML had been inundated with hundreds of social media posts along the same lines, questioning the decision to hire Westgaph due to past convictions for violent assault and statutory rape of a 15-year-old girl. But the significance of the private message to Dugdale was that, though it didn’t say so explicitly, it came from a woman who had experienced serious sexual and emotional abuse by Westgaph.

By not replying and engaging with this woman, NML missed an opportunity to learn the true horrors of Westgaph’s abuse, which The Post can report for the first time today. Via conversations with 16 sources and documents that support their allegations — including messages from Westgaph himself in which he admits disturbing behaviour towards one of his ex-girlfriends — we can paint a picture of a man who has repeatedly abused, stalked and coerced his romantic partners, some of whom say they are still scared of him to this day.

Our reporting also shows that NML failed to act on a series of warnings from its own staff that Westgaph was touching female colleagues inappropriately and making women feel uncomfortable, all the while allowing Westgaph to have contact with young people — a stunning failure of safeguarding that NML has not explained. As one serving staff member put it to The Post: “How do I bring young people in [to the museums] when there's this monster here?”

In light of this story, NML says it has launched an internal investigation into Westgaph, who left his role as resident historian last year, and is “encouraging any colleagues who wish to come forward with related information.” A legal firm representing Westgaph has so far not answered any of the detailed questions sent by The Post just over a week ago, repeatedly stating that Westgaph needs more time and the names of each victim involved in order to answer the claims. Westgaph’s lawyer says he denies all the allegations and that he has been the victim of a plot by an ex-partner to sully his name. They provided us with the following statement from Westgaph:

“I have been presented with a long list of wholly unparticularised allegations made against me. Notwithstanding this, I categorically deny all wrongdoing. I have been told that these allegations have been referred to the police. I am committed to fully co-operating with the police with any enquiries they have. I have however not been charged or questioned in connection with any of these allegations (some of which are 23 years old). Although very serious allegations have been made against me (which I emphatically deny) it would be inappropriate for me to comment further on matters which have been referred to the police”.

Liverpool’s worst kept secret

When Millie met the historian, activist and television presenter Westgaph around six years ago, she was instantly enamoured. Tall, handsome and fashionably dressed in 70s style flares and boots, Westgaph is a recognisable figure in Liverpool. He also has a national profile, having presented historical documentaries on the BBC and the History Channel and running popular walking tours around the city. Last year, he was crowned the second most influential black Scouser by the news site LiverpoolWorld.

At first, Millie’s relationship with Westgaph felt like a dream. She says he would lavish her with praise, showing up unannounced at her home or workplace to surprise her. But by her account, he soon began to reveal a darker side: isolating her from her friends and family; belittling and degrading her; and coercing her into violent sex. Whenever she separated from him, he would park outside her house, leaving something with his name on the seat — “so I always knew it was him,” she remembers. He would bombard her with text messages and even tried to force his way into her home.

The onslaught became so bad that Millie installed security cameras and became paranoid. At one point, she says she wrote a letter to her friend detailing his name and address, in case she ever went missing. There’s no evidence that Westgaph posed a risk to her life, but even now, several years later, she still checks under her bed and in her wardrobes whenever she comes home.

Millie isn’t the only woman who’s experienced this kind of behaviour from Westgaph. Over the past month, The Post has uncovered a frightening pattern of abuse, violence and coercion spanning the last two decades, including incidents NML could have discovered if it had made any effort to vet the man they were hiring in 2020. One person we have spoken to describes Westgaph’s abuse as one of Liverpool’s “worst kept secret[s]”.

Many victims of Westgaph’s abuse tell The Post that they didn’t go to the police with their stories because his career and influence have so far remained largely unaffected by past criminal convictions and widely-spread rumours about his behaviour. “I know the reputation he has with women, but I also know the reputation he’s somehow managed to uphold regarding his status and how many people advocate for him and trust him,” Millie says. “I was just like, why would anyone ever believe me?”

Producing this kind of journalism takes months of research, rigorous fact-checking and interviews with vulnerable sources. If you want more stories like this delivered directly to you via email, you can sign up to our mailing list for free using the button below. You’ll be joining 32,000+ readers already on our list, and you'll also be supporting us in our mission to deliver a renaissance in high quality local journalism.

A culture of silence

Born in 1975 to a mother of Nigerian descent and a Jamaican father, Westgaph spent his childhood in Toxteth, leaving school at 16 to embark on a modelling career. It wasn’t until the early 2000s, when Westgaph was in his late twenties, that he pivoted to academia, completing his master’s degree in Atlantic History at the University of Liverpool in 2008.

During his time at university, Westgaph became a go-to source on the history of slavery for the BBC. He appeared in numerous television and radio programmes, including The Routes of English on BBC Radio 4, and was given a column in the Liverpool Echo. He later embarked on a PhD at the University of Liverpool, as well as forming the Liverpool Black History Research Group that is still in existence today.

When he was hired as Historian in Residence by National Museums Liverpool (NML) in August 2020, Westgaph was already a member of the institution’s RESPECT group — established in 2008 to advise the museum on black representation. Additionally, his Liverpool Black History Research Group was a stakeholder in the multi-million pound revamp of Canning Dock as part of the Waterfront Transformation Project. Through these roles, he came into contact with the museums’ Youth Engagement groups and Youth Ambassadors — some as young as 14.

At the time of his hiring, Janet Dugdale, then-Executive Director of Museums and Participation, said that in addition to Westgaph helping the institution achieve its promise to be anti-racist, he would be “extremely valuable” in his new historian role — “his knowledge of Liverpool as a city is critical in helping us realise our goals and inspiring our visitors to think differently,” she said.

Her statement didn’t address Westgaph’s past criminal convictions, news of which was soon being shared widely on social media. Westgaph had been arrested in 2008 for attacking a man named Ben Blance in the home of his former girlfriend, Natalie Inge. A court heard that after breaking into Inge’s home and finding the two in bed together, he’d attacked Blance, punching him several times and fracturing his eye socket. “I was taken aback at how savage he was,” Blance told the court at the time. He was left with double vision after the assault.

Westgaph pleaded guilty to causing grievous bodily harm, and despite the vicious nature of the attack, he was given a suspended sentence. In part, he had Bafta-winning scriptwriter Jimmy McGovern and former MP Lord David Alton to thank for the leniency — both gave character references vouching for him. His defence lawyer also argued that the assault was “out of character”, and that any custodial sentence would be “devastating” for his career. This is despite the revelation in court that police had been called to the home of his ex-girlfriend Natalie Inge on two separate occasions before the attack.

This article was published by The Post. If you want more stories like this delivered directly to you via email, you can sign up to our free mailing list using the button below.

Westgaph also had a previous conviction for statutory rape of a 15-year-old in 2000. His defence lawyer argued the girl gave “every impression” of being older, and he was given a community order.

The Rehabilitation of Offenders Act of 1974, which governs what are known as “spent convictions” in UK law, means that after a certain period of time, a former offender does not need to declare their previous convictions when applying for a job. However, there is an exemption that means employers are entitled to consider spent convictions when the role involves being around children or vulnerable people. National Museums Liverpool has not answered our questions about how it considered Westgaph’s convictions when appointing him in August 2020. (It also carries legal risks for media companies to mention spent convictions in articles like this. Having taken legal advice, The Post is confident that there is a strong public interest argument for mentioning Westgaph’s convictions because of their direct relevance to the other allegations mentioned in this story and his hiring by a public institution).

Staff members working for NML in 2020 tell The Post they were only informed of Westgaph’s employment as Historian in Residence after it was announced on social media. “I remember being in a team meeting when my manager told me [Westgaph] had been hired,” one employee says. “I hadn't come across him before and I Googled him. Of course, then I was like ‘What the fuck?’” According to multiple employees, they were told not to speak to the press about Westgaph’s employment. “They want[ed] to control the narrative,” another member of staff says.

When we asked NML why they had hired Westgaph despite his past convictions, and if they were aware of more recent allegations of harassment in the workplace and domestic abuse in his personal relationships, a spokesperson denied they had received any “internal formal complaints about his behaviour”. They did not address our specific questions about what they knew and when.

A Freedom of Information request (FOI) was filed by a member of the public the day after Westgaph was hired, asking for details about his historian role and the hiring process. More than four years later, that request still hasn’t been answered — despite the legal obligation for organisations to respond within 20 working days. (NML now says they apologise for failing to answer the FOI and invited the member of the public to resubmit it.)

In the months after Westgaph’s hiring, female members of staff began raising concerns with management about working with him. But according to one source who works at NML, Dugdale told them “the risk of working with him is outweighed by the reward”.

It wasn’t just staff members who complained to the museum. There was also the woman who reached out to Dugdale on Twitter, informing her that Westgaph had a track record of “sexual and domestic violence”. We contacted Dugdale but she told us that as she no longer works for NML, she was unable to answer our questions.

Female employees of NML say Westgaph soon made them uncomfortable. One woman says he “made excuses to touch” her, including putting his arm around her, brushing up against her and asking her for hugs. She witnessed him sit unnecessarily close to female staff, touching their thighs.

“[Women] have said things like ‘I don't want to work on my own with him’,” another employee says. Full-time staff at the museums who came into contact with the public were required to have so-called “enhanced DBS checks”, which stands for the Disclosure and Barring Service. This employee alleges that Westgaph did not have such a check and that this was sanctioned because he was hired as a freelance contractor rather than a pay-rolled member of staff.

This is a claim we’ve heard from multiple sources — so we asked NML about it. They did not address this question in their response to us, but told us:

“National Museums Liverpool has not received any internal formal complaints about his behaviour, but in light of these recent enquiries we will be opening an internal investigation and encouraging any colleagues who wish, to come forward with related information. We take the welfare of our colleagues very seriously and have in place a ‘Speak Up’ process, whereby issues such as bullying, harassment and safeguarding concerns can be raised and investigated internally. In addition, colleagues have access to an Employee Assistance Programme through which they can get professional advice and counselling.”

The spokesperson also clarified Westgaph was contracted as a freelance Historian in Residence and his employment terminated in June 2024 as it was “freelance contract work and the contract ended”.

After sending us this statement, we asked NML to explain what they meant by “internal formal complaints”, and if they ever received any other form of complaint about Westgaph. We also asked about his contact with children and women, his other roles at the organisation and how that aligns with NML’s safeguarding policy. They told us: “We have nothing further to add to our statement”. Whether this position will hold in the coming days remains to be seen.

An ‘alphamale’

“He does this humble, sort of intellectual character for the rest of the world, and it’s almost impossible to imagine that version could be so violent,” says Elizabeth, one of the women we spoke with who has had a romantic relationship with Westgaph in the past.

She tells me that when she dated Westgaph around ten years ago, he was “insanely charming” and would text her incessantly. Their relationship was a whirlwind, with Elizabeth admiring his work for the black community in Liverpool. But within six months or so, she noticed a different side to the upbeat, soft-spoken man she knew. As he’d done with Millie, he gradually stopped her from seeing her friends and family, claiming they didn’t like him or were a bad influence. He began intimidating her with his size, pushing her against walls and shouting at her. He’d call her a “whore” and tell her she was “no better than a prostitute”.

Elizabeth, Millie and others we’ve spoken with say Westgaph could be “very forceful” during sex. “He would use sex as a punishment,” Millie explains — if she obeyed him, the sex would be “quite intimate”. If she didn’t, “I was taken by the throat” and pressured to engage in anal sex. “He was obsessed with the idea of being the only man who had done that to me,” Elizabeth says. “It wasn't something I was comfortable with but he pushed for it continuously.”

Sometimes, she tells The Post, she would wake up in the middle of the night and he would be having sex with her. Attempting to push him off, she’d cry and beg him to stop. The next morning, she’d try to speak with him about it. “He would call me crazy,” she says, “then he'd say, ‘Well, if it did happen, I was asleep so I was unconscious, so I can't have a conversation with you about it’”.

During their relationship, Elizabeth heard rumours about his violent past towards his former partners. Yet Westgaph worked fast to cloud her judgement. “He pre-emptively told me stories before people tried to warn me [about him],” she says, explaining he’d told her all about his “crazy” exes trying to sabotage his relationships by calling him an abuser. “My grounding of what was real or not got quite blurred.”

Millie says Westgaph regularly referred to himself as an “alpha male”, another detail that several other of his partners we have spoken to have mentioned (most of the women we have spoken to for this story do not know each other). Another thing they describe is obsessive behaviour akin to stalking when they’d try to leave their relationship with Westgaph. “There was literally no escape,” Amanda says. She dated Westgaph around fifteen years ago, and “multiple times I tried to end the relationship, he would constantly draw me back in.”

Sophie, who also dated Westgaph nearly twenty years ago, says she “went through so much with him, and also to get away from him”. During her time with Westgaph, he would denigrate her looks, “pointing out every single imperfection on my face…and telling me how ugly and unworthy I was of him.” He tried to convince her that she was “psychologically unstable”, regularly calling her “crazy” and telling her she’d done things or been to places she hadn’t. “That’s the sort of cruelty and mind games he would play with [me]”.

Five of the women we spoke to recall that one of the ways in which he would coerce them back into relationships with him was the promise of a life in Spain. Westgaph has a property there, and he would tell those he dated he wanted to relocate permanently with them. “He would tell me this fantasy of how we’d live there together… and all this wholesome stuff,” Elizabeth tells me. “As far as I know, that dream was being sold to many women at the same time.”

‘He's pretending to uplift us’

In June 2022, Faris Khalifa was attending Africa Oye Festival in Sefton Park. He'd been enjoying the live music with his friends, when, out of the blue, he says he spotted Westgaph hurtling towards him. “He started shouting at me, saying that I’m a rat and such, and asked me to go to the parking lot to fight him,” Khalifa says, adding that Westgaph spat on him. “He was swearing and it was literally in the middle of the most busy festival in the city, and there’s kids everywhere.”

This article was published by The Post. If you want more stories like this delivered directly to you via email, you can sign up to our free mailing list using the button below.

Khalifa had been an outspoken critic of Westgaph’s for some time. He was aware of his abusive behaviour towards women, and he had criticised him to friends and acquaintances. He believes this prompted Westgaph’s verbal attack. “He was just being very aggressive and shouting, and I was just telling him to calm down,” one witness of the altercation remembers. The incident was reported to Merseyside Police, who issued the following statement: "We are appealing for information after a man reported he was verbally abused by another man while attending Africa Oyé in Sefton Park on Sunday, June 19. It was reported on Monday, June 20 that a man in his 30s had been verbally abused while attending the music festival at around 7.45pm on Saturday.”

The Echo also approached Khalifa for an article they were writing about the incident. However, when the piece was published, it did not name Westgaph. Despite this, rumour quickly spread that he was the man responsible. The incident was, after all, in the middle of Sefton Park on one of the busiest days of the year and was witnessed by dozens of people.

Soon after the Echo’s story, Khalifa was inundated with messages from women informing him they had been abused by Westgaph. “I was like wow, this is bigger than I thought it was,” he says.

The following week, he emailed National Museums Liverpool (NML) and informed them of the attack. The email subject: “I WAS ATTACKED BY LAURENCE WESTGAPH”. Later, the head of the International Slavery Museum, Michelle Charters, called Khalifa, and reassured him that there would be a thorough investigation into Westgaph’s behaviour. While Khalifa was told he wouldn’t be informed of the outcome of that investigation, he felt satisfied the museum was taking his concerns seriously. Two years later, Westgaph was still employed by NML.

“Nobody who wants to represent us as black people would ever do the things he does,” Khalifa told The Post. As a refugee fleeing his home after his family was murdered in the Sudanese Civil War, the attack in 2022 severely triggered his PTSD. He’s upset that Westgaph has continued to work for the museums despite his behaviour. “He's pretending to uplift us when he's really doing horrific things,” he says. We asked NML about the incident at Africa Oye and the subsequent report made by Khalifa but they did not address our question in their statement.

The attack in 2022 was not the first time Westgaph had been reported to the police for a violent outburst. Back in 2008, shortly before his court case for attacking Ben Blance, Westgaph had assaulted yet another man named Andy Lad. Westgaph had begun dating an ex-girlfriend of Lad’s, and had become paranoid that she was seeing Lad again after they’d split up.

In the middle of the night, Lad says he woke up to a loud knocking at his door. It was Westgaph, and he was demanding to be let inside. Lad, not knowing Westgaph well, obliged, and the pair began a heated conversation over the woman they had both dated. “He's a big lad, but I wasn't that intimidated by him,” Lad tells me. “I think he's not used to people not being scared of him”.

After asking Westgaph to leave multiple times, Lad picked up his phone to call the police. Westgaph leapt up from his seat, smacking the phone from his hand. Lad says he headed upstairs to his bedroom but was followed by Westgaph. Upon entering his bedroom, Westgaph allegedly punched him in the face before fleeing the property. Lad says he reported this incident to the police, but never followed it up to find out the outcome. We asked Westgaph about both of these incidents but he did not address our questions in his statement.

“Somebody at the International Slavery Museum described him to me as their moral conscience, and honestly, to hear that is how people see him is really disturbing,” says Amanda. While it’s been nearly two decades since her relationship with Westgaph, she still struggles with forming relationships with other people. When she hears loud noises or is startled, she has “physical reactions in her chest”.

“I didn’t know what was real and what wasn’t; I’ve still got no idea,” Elizabeth says. She struggles to make sense of what happened to her, with Westgaph’s voice often in her head, tormenting her. When she’s asked about her thoughts or opinions, her likes or dislikes, she finds it hard to know if her answers are hers alone. “I’ve talked in therapy about it over and over again, and I think that’s why emotional abuse is so effective,” she says. “Because you can’t pin any of it down. It takes a lot of time to trust yourself again, to make decisions on even small things.”

Westgaph may no longer be employed by NML, but he still seems to have a presence there. One staff member saw him at an event as recently as last month, and says he is still involved with the RESPECT group and Waterfront Transformation Project. “His behaviour is so brazen because he thinks he can just get away with it. He knows the museums will stick up for him,” the staff member says, something they describe as “shocking and upsetting”.

She asks me a rhetorical question: “How do I bring young people in [to the museums] when there's this monster here?”

Thank you for reading today's story about historian Laurence Westgaph. If you want more stories like this delivered directly to you via email, you can sign up to our free mailing list using the button below.

If you were affected by this story, or have any further information to share with us about this subject, please email editor@livpost.co.uk.

Read the follow-ups to our investigation below:

Comments

Latest

Fountains, Ffrith and turning the place over

Just what is happening with Peak Cluster’s CO₂ pipeline?

A ‘stitch up’? How Wirral council bungled Big Heritage

Merseyside’s buses are coming back into public hands. Why not trains too?

Laurence Westgaph was a known abuser. Why did National Museums Liverpool look the other way?

A Post investigation reveals how the city’s biggest cultural institution ignored allegations of sexual and domestic violence against its resident historian