How Liverpool invented Christmas

Every Christmas pudding tells a story of Liverpool’s innovation, enterprise and ambition — with a large helping of exploitation too. Did our modern Christmas start in our docks?

🎶It's beginning to look a lot like... you need to sort out your Christmas presents pronto 🎶

Don't worry, your old friend The Post is here to help. We're offering a whopping 50% discount on gifted annual memberships (just £49.90) to make your Christmas shopping easier, or you can get them a three month (£19.90) or six month (£39.90) option - and give us extra support at the same time!

Not only that but the clever computer people have created a way for you to automatically send your giftee a nice message on Christmas day as their subscription starts (perhaps: "you're such an interesting person, you're bound to love the huge range of fascinating articles you'll get over the next year...")

In 1845, Eliza Acton published a recipe for ‘Christmas Pudding’ in her bestselling book Modern Cookery for Private Families. Every aspirational housewife prayed there’d be a copy stuffed into her stocking. And, yes, they prayed they’d have one of those new-fangled Christmas trees to put it under, too.

Acton’s scrupulous recipe proved to be an instant hit. So much so that it was more-or-less pilfered, twenty years later, by Mrs Beeton in her Book of Household Management.

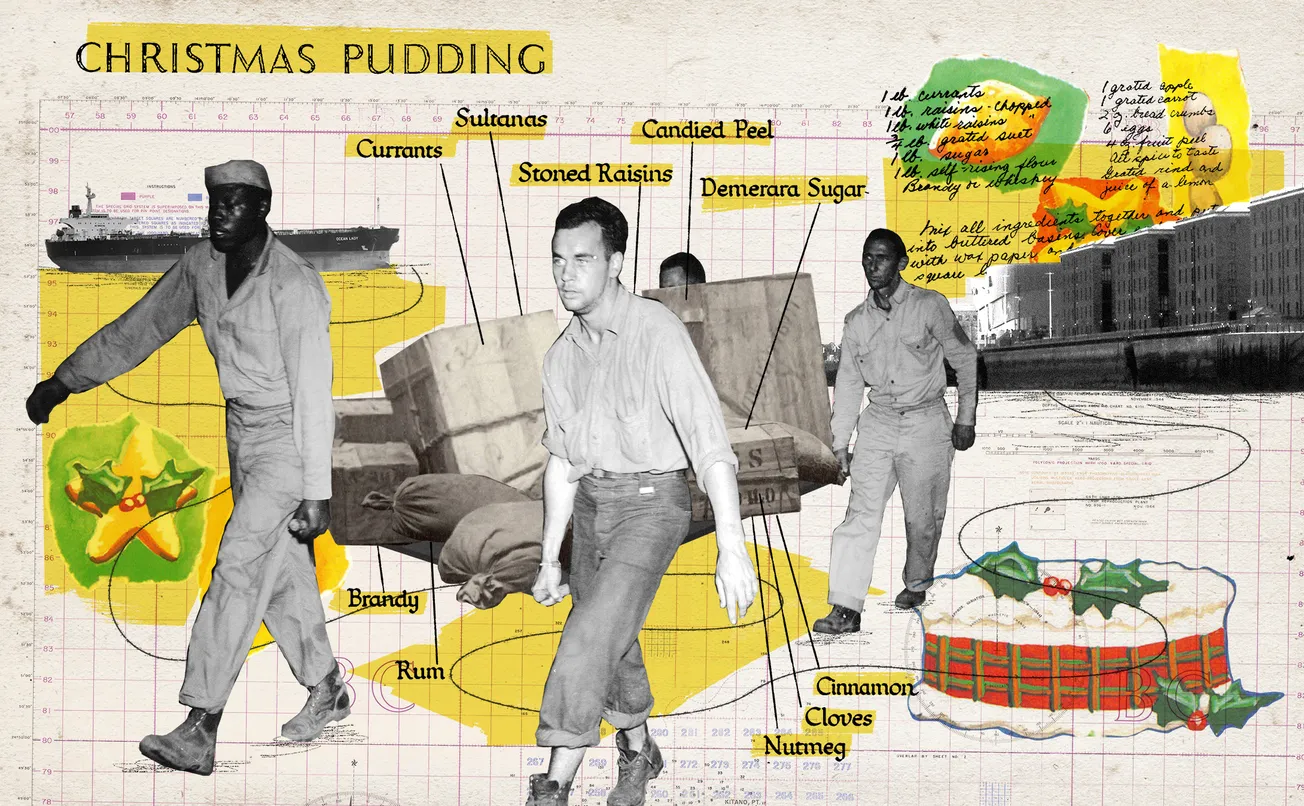

But the recipe was incomplete. Eliza failed to list one crucial ingredient, without which the whole gooey enterprise was destined to fail. That ingredient? Liverpool.

The next time you slice into a rich, brandy-soaked Christmas pudding (which I'm guessing will be next week. And then, after a couple of spoonfuls, be reaching for the Cadbury's Heroes instead) or take a thick, glistening slice of Christmas cake, spare a thought for our port.

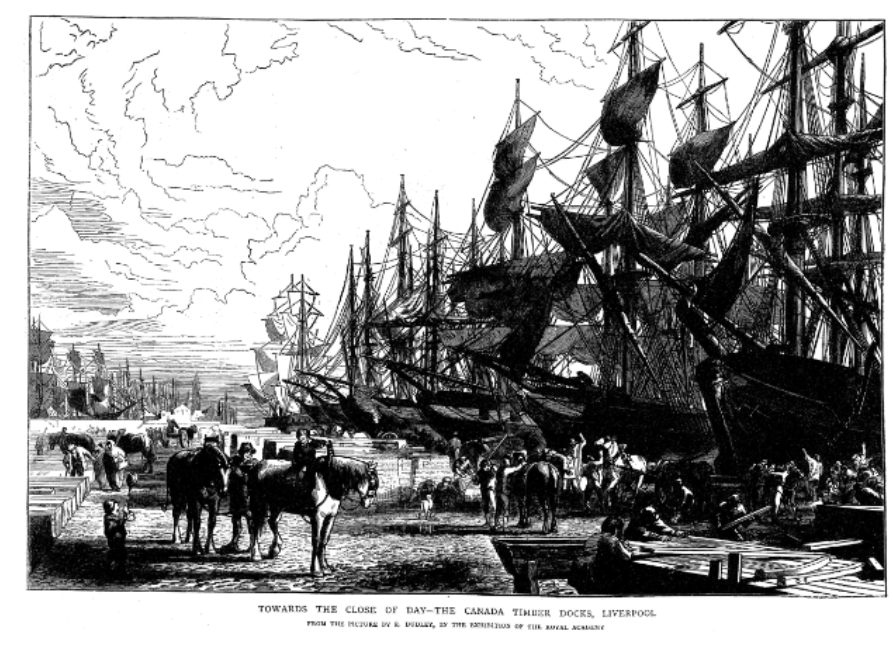

Without these bustling Victorian docks, your Christmas table — and the teetering towers of mince pies lining the aisles of Iceland, for that matter — would look very different indeed.

Before the expanding trade routes into our city brought greater quantities of dried fruits (currants, raisins, figs, apples and dates) and spices to Britain, we’d be filling our mince pies with minced meat (I suppose the clue's in the name), Christmas cake wouldn't exist at all (the Victorians more or less invented it), and you'd be having frumenty instead of fruit pudding: a thick porridge made with boiled grains. Yum.

Our cherished Christmas treats are actually edible monuments to globalization, if ‘monument’ is the right word: the sugary luxuries being spiked with a decidedly sour history of colonialism and slavery.

"The Christmas cake and pudding are made from relatively exotic ingredients," Ian Murphy, Head of Liverpool's Maritime Museum, tells me. "They're not items people would see any other time of the year. We forget how luxurious they would have been back then. It was only as Christmas was approaching that you began to see them arrive into the city.”

Every ingredient that made the Victorian Christmas table special – the raisins, the exotic spices, the candied peel, the sugar, the brandy and rum – comes from somewhere else entirely. And in the 1840s, almost all of it was unloaded right here.

"Prince Albert triggered the whole Victorian Christmas craze, but Liverpool helped drive it," Murphy notes. "By this time, Liverpool was already importing sugar, rum and other fruits from British colonies from around the Caribbean. By 1840 we're on our way to being the second biggest port in the world."

If you're enjoying today's piece and want to read more stories like this, then please subscribe to The Post. We're an award-winning email newsletter that sends you heartfelt features, proper local journalism and peerless writing about life in Merseyside. 35,000 people have already joined our mailing list. Hit that button below to join up for free.

These symbols of cosy domestic tradition were only possible because of Britain's vast imperial reach and our city’s cutting-edge industrial logistics. The Victorian Christmas table wasn't just about family values, it was a display of global commerce, sitting there steaming in a pudding basin.

Victorian celebrity chef, and Queen Victoria's personal cook, Charles Elmé Francatelli published a recipe in 1846, which called for: raisins and currants from the Mediterranean, candied orange and lemon peel from southern Europe or the West Indies, sugar from Caribbean plantations, nutmeg and cinnamon from Asia, and brandy or rum to set the whole thing aflame. Not a single ingredient was native to Britain.

"Ship by ship, the imports were logged in the daily Customs Bills of Entry, from the Port of Liverpool," Murphy says, highlighting the meticulous record-keeping that tracked this transformation.

I head to the Maritime Museum’s archives just off Dale Street, and scroll through rolls of microfiche, looking at the imports into our city in early December in the 1840s. It’s practically a shopping list, albeit peppered with imports such as ‘26 tonnes of Old Junk from Antwerp’ — it’s unclear whether this was the original name for Old Spice — and, pleasingly, ‘two cases of Guitars’ from Malaga destined, no doubt, for the Victorian Beatles.

We might think we invented the Christmas food fad when Nigella did that roast chicken recipe with pomegranate molasses, and we all flocked to Sainsbury's to hoard jars of the stuff — but the Victorians got there first.

There it all is, line by line, ship by ship: Christmas imports listed in staggering quantities, from all corners of the world: oranges and lemons from Palermo, raisins from Malaga, lemon peel from Genoa, currants from Antogagasta in Chile, Oysters from New York and apples from Boston.

For a quick snifter? Port, Madeira and brandy from Porto, Lisbon and Charente in France – imported by Liverpool’s Harrison Line. Almonds from Alicante, cinnamon and cloves imported by Liverpool's Blue Funnel Line from Bombay and Shanghai; cranberries from Quebec; rum from Guyana; hazelnuts from Smyrna in Turkey; molasses from Trinidad. And from Bergen? A wooden rocking horse.

In one single December day in 1846, the port of Liverpool unloaded 1500 gallons of port, 200 butts of currants from Malta (casks holding 500 litres), 25 chests of chestnuts from Porto, 400 boxes of raisins from Gibraltar, 865 bags of hazelnuts from Turkey and 200 puncheons of rum (around 70,000 litres) from Antigua.

And, the next day, it would do it all over again.

"Pre-refrigeration, Liverpool even imported ice to keep perishable products fresh," Murphy explains. "Our port was just better set up for fruits, way back to the 17th century." Liverpool and innovation went hand in hand, even before the first commercial wet dock was built in 1715.

Liverpool wasn’t known as a Mediterranean port, but according to Murphy, the city’s long history of trade with Spain and Portugal meant we have a legacy of importing fruit.

One name stands out in these annals: McAndrews, one of the earliest and biggest fruit importers. "They were trading from Spain and Portugal, and importing into Liverpool warehouses, back in 1770," Murphy says. The company is still trading today, although their warehouses in George’s Dock were demolished and the dock infilled to create the Pier Head.

By the Victorian era, Liverpool had become what UNESCO’s World Heritage committee, in their brief dalliance with the city, called "a supreme example of a commercial port." The opening of the Albert Dock in 1846, with its cutting-edge hydraulic cranes and purpose-built warehouses, set new standards for maritime logistics, as well as for delicately handling currants. You don’t need me to tell you about the currant boom of the mid-19th century, when we couldn’t get our hands on enough of the little black sugar bombs, do you? Thought not.

Victorian dockworkers were in a race against time to unpack festive shipments. “Speed mattered, especially for the delicate goods that would end up in your Christmas pudding,” Murphy says. “Dried fruit could spoil. Spices could lose their potency. The faster you could unload a ship and get its cargo into climate-controlled storage, the lower your losses, and the cheaper the price for consumers.”

Liverpool's infrastructure was specifically designed to handle not just the massive cotton bales that were its bread and butter, but also the high-value, perishable goods that would transform our Christmas.

At the heart of it all was the sugar route. Liverpool had dominated transatlantic trade since the 18th century, and sugar — along with rum and molasses — was its sweetest cargo.

On islands like St Kitts, these products made up a staggering 92% of exports in the 1770s. It was a trade built on slavery. "That trade made us an incredibly wealthy port in the 18th century," Murphy says, "and increased supply meant more families could afford these luxuries.”

Even after abolition within the British Empire, the cheap sugar that transformed Christmas pudding from a savory pottage into a sweet dessert was still produced by enslaved and exploited workers on plantations across the globe.

If you're enjoying today's piece and want to read more stories like this, then please subscribe to The Post. We're an award-winning email newsletter that sends you heartfelt features, proper local journalism and peerless writing about life in Merseyside. 35,000 people have already joined our mailing list. Hit that button below to join up for free.

It’s hard to imagine these days, in a city where improved transport is always a ‘jam tomorrow’ pledge, but the coordination required to manage these supply chains was extraordinary. The Christmas pudding demanded all these ingredients at once. Liverpool solved this intricate logistics puzzle so efficiently that, for the first time in history, all the components arrived reliably and cheaply enough for ordinary families to purchase them. And here’s me, nearly two centuries later, unable to get to Crosby when Everton are playing at home.

The timing was crucial. "By the 1840s, as ships changed to steam, they became bigger and more reliable,” Murphy says. “At that point the scale of trade drove prices down further," This technological shift coincided perfectly with the Victorian Christmas revolution. It also saw our docks’ huge expansion: between the 1820s and the 1850s over 140 acres of new docks, and 10 miles of quays, were built to accommodate the increased trade.

"The other key element about Liverpool being a major port is that it's set up for trading," Murphy says. “The city had already developed a global network of merchant houses with branch offices across the world.” We were ready – and able – to ramp up when Christmas meant business.

Trade directories from the 1860s reveal the emergence of a new commercial class: wholesale coffee and spice dealers on the now-lost Cable Street, specific fruit brokers like James A. Sons & Co, and provision merchants who managed the delicate balance between global supply and local demand.

Victoria Street had been a hub for fruit merchants and warehouses since the late 19th century, thanks to its proximity to the docks and Exchange railway station.

At first, fruit trading happened through individual dealers' offices, open markets, and the nearby Produce Exchange (opened 1888), but with the arrival of the grand Fruit Exchange in the early 20th century (now slated to be an 81 bedroom hotel after years of dereliction), the market exploded.

On this point, Murphy gets existential. "The reason Liverpool exists is to make money out of the imports in the port. So it built up a really good infrastructure for merchants, selling into the city and the hinterland.”

And Liverpool's success in bringing the Victorian Christmas to our table did more than just fill pudding basins — it helped the city to grow fat on the fruits of its labour. The city's great department stores, like Lewis’s, Blackler's and Owen Owen, became Christmas shrines, showcasing the seasonal treats that these reliable supply chains now made possible. Maybe that’s how Blackler’s got its rocking horse, too?

These days, Christmas arrives into Liverpool docks thanks to those huge container ships, laden with crap from Temu and Shein. Back then, while Liverpool didn’t technically invent Christmas, it came into Salthouse and Albert docks, smelling sweetly of cardamon, cocoa and currants.

The Port of Liverpool didn’t just respond to demand: it helped create a market for fruits and spices — sourcing new ingredients, setting prices and transporting its produce inland. Without our city’s innovation and infrastructure none of this would have been possible, and our mince pies would still be filled with mutton. Our city’s specialist brokers transformed the exotic into the ordinary, and imperial spoils into family traditions.

In doing so, our city shaped not just what we eat at Christmas, but how we celebrate it too. A tradition built in no small part by the docks of Liverpool. Ingredient by ingredient, merchant by merchant, ship by ship.

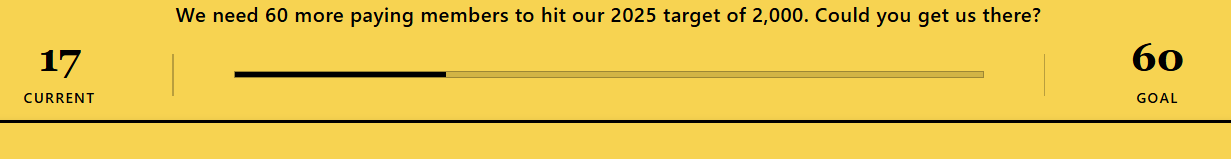

As you can see from the tracker on our homepage, The Post is a little way off hitting our goal of 2,000 paying members before the end of the year.

So why not help us out? Because it's Christmas, we're offering a whopping 50% discount on gifted annual memberships (just £49.90), so you can get a three-month (£19.90) or six-month (£39.90) subscription from us in time for the New Year. Click here to grab that deal.

Or, if you'd rather pay month-by-month, then feel free to use our introductory offer to pay just £1 a week for the first three months. Click the button below for that.

Comments

Latest

The lost department stores of Liverpool

From Simone's to Belzan: How a hospitality magnate seduced Liverpool's tastemakers

Last minute drama, local revamps and Liverpool Doc Club

Is Williamson Square Liverpool's own Times Square?

How Liverpool invented Christmas

Every Christmas pudding tells a story of Liverpool’s innovation, enterprise and ambition — with a large helping of exploitation too. Did our modern Christmas start in our docks?