From Merseyside to the Middle East: Rae McGrath's mission to rid the world of landmines

Operating out of a cottage in Cumbria, one man's war to disarm military zones

Today's piece is about the incredible life of Rae McGrath, a Liverpool-born bomb dismantler who, for the past four decades, has worked across the world saving hundreds of lives. It's an incredibly important story to tell, but we're only able to publish articles like this thanks to the support of our paying members.

If you've been enjoying our work and believe in the need for quality local journalism like this, please join up to The Post today for just £1 a week. In return, you'll get access to our entire back catalogue of paywalled stories, receive all our extra editions per month, and be able to come along to special members-only events.

It is a little before 7am in Laylan, northern Iraq, and the July heat is already almost unbearable. The road that passes by has been closed off, and a couple of cars wait patiently at roadblocks at either end. They’re used to this, every Thursday morning. It only lasts an hour or so, and the reward for patience is something quite impressive the first time you see it.

For the previous few days I have been following various teams from the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) around northern Iraq, observing their operations across lush mountain regions and abandoned towns. At each location, the work is difficult and dangerous in the searing heat; locating and removing unexploded mines and ordnance, left over from decades of conflict in the region. Today, anything they have found is gathered and buried in the sand on a hillside in the middle of the Laylan desert. From a safe distance, I watch with the team from MAG and observers from the Iraqi Kurdistan Mine Action Agency as the countdown begins, and then the side of the hill explodes outwards, the plume of rising smoke and dirt followed seconds later by an ear-splitting boom. Then the road is re-opened and the sporadic local traffic continues to pass through the desert as the smoke dissipates into the blue sky. Another batch of landmines, unexploded bombs and home-made terrorist devices has been removed from communities and destroyed. But with a United Nations estimate that there are at least 10 million pieces of live ordnance in this part of Iraq, Kurdistan, alone, there’s a long way to go.

3,300 miles away, in central Manchester, around 60 staff from MAG co-ordinate the efforts of 5,000 operatives in 40 countries, from Asia to the Middle East to Latin America. Kurdistan in northern Iraq, where I spent a week with MAG, was the very first project the NGO embarked upon in 1992. This year, the organisation was recognised with the Conrad N Hilton Foundation Humanitarian Prize — worth US$3 million. Presenting the award in August, Peter Laugharn, the Foundation’s president and CEO, commended MAG for “its extraordinary efforts to help communities return to safety and prosperity after conflict.” It’s an incredible honour for an organisation that has helped more than 23 million people in 70 countries rebuild their lives after war and conflict, one that began on the streets of Liverpool, six decades ago, where a young Rae McGrath was tarmacking roads as part of a team of navvies.

Raphael McGrath was born on bonfire night, 1947, the flashes and bangs of the November 5th celebrations laying out the path the boy who became known as Rae would follow. But if it was destiny, it wasn’t apparent for the early years of his life. Rae grew up in a family of eight children in a three-bedroomed house in Dovecot, Liverpool. He recalls, “I didn't know I was brought up in a very rough place until I was watching a black and white documentary one day, and realised they were talking about Dovecot, and I thought, ‘wow’.”

The family moved across the water when Rae was 13, to Birkenhead, where he finished his unremarkable state schooling, leaving without any qualifications. He began work as a labourer, in all kinds of jobs. In 1964, Harold Wilson’s Labour had won a narrow election victory, and by the following year the country was in economic crisis. “It was one of those periods where everything was on the downturn,” says Rae. “If you were on the dole you didn’t really have a chance of getting a decent job. So I mostly did labouring, warehouse work, road building".

“A couple of smart guys working on the roads said, you need to get out of this if you’re going to do anything with your life, otherwise you’ll end up like us, a navvy when you’re 50.” One of the men was Irish, and said while it might sound strange “coming from an Irishman” — discontent was growing in Northern Ireland and in 1969, just a year after this conversation, British troops would be deployed, heralding the beginning of the Troubles — he advised Rae to join the military and get himself a trade.

Hello there! Welcome to The Post, your go-to source for in-depth journalism about Merseyside. From important cultural reads like today's story, to hard-hitting investigations exposing corruption, you can guarantee nothing but the best quality news from us — Scout's honour.

You can get two totally free editions of The Post every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. Thanks!

So Rae, aged 21, walked into the Army recruiting office in Birkenhead, having told nobody, not his family, not the girl he was engaged to, what he was planning to do. And when he walked out he was an electrician in the British Army’s Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers. That was the plan, anyway. “The problem was I was hopeless at maths,” laughs Rae. “And without maths it’s pretty hard to be an electrician.” Rae, now in his early 20s, was re-deployed as a recovery mechanic, or “recce mech” — going out in the field to work on military vehicles. He soon discovered this was something he was actually pretty good at, going on to serve in Germany, Northern Ireland, Hong Kong and Cyprus. And while in the Army he had his first brush with landmines.

When I visited MAG’s operations first in Iraq in 2021 and then, in 2023 in Vietnam, I was surprised by how hands-on the procedure of mine clearance is. There is technology — hand-held detectors, large ring detectors to cover a greater area and uneven terrain — but when it comes to the crunch, it’s one person, lying flat on their stomach, poking a metal rod into the earth. MAG’s policy is to train local people to be de-miners. For many, it’s the best paid and most secure job they’ve ever had. There are both men and women working as de-miners — in Iraq and Vietnam I saw teams of all-women operatives. I asked them why they do it, and if going to work every day didn’t fill them and their families with terror. To the second question, they always shrugged and said MAG’s training was exemplary, and if they followed the procedures, then it was entirely safe.

As to why they do it, it’s to reclaim their land, their homes, their agriculture. And that’s something that didn’t really occur to Rae for a long time, even as he began his work on landmine contamination in the mid-1980s.

As a recce mech, Rae had to be fully trained on landmine removal, because even in the 1960s and 1970s, contamination from World War Two was still a problem, especially in France, Belgium and Germany. He explains: “If tanks and other vehicles have broken down or been hit, they might be in a minefield or have been booby trapped. So you have to clear a path to recover them.” Rae had a talent for it in the same way he had no talent for maths, and soon he was running training courses on mine-clearance. It was always about recovering the Army’s resources, though, something he didn’t question for a long time. “Nobody cleared minefields,” he says. “It was never suggested. You cleared a path to get to a stranded vehicle but the rest of the mines… it wasn’t an issue. I felt stupid years later when I realised this. There were mined areas and nobody had any interest in clearing them.”

After 18 years, Rae had had enough of the Army. He came out in 1985, aged 38, just four years away from his pension. Leaving wasn’t a decision that sat well with everyone; his marriage broke up and he ended up homeless, living in his car. But word of his expertise in vehicle recovery in difficult environments had spread, and suddenly he was getting phone calls from humanitarian organisations asking for help.

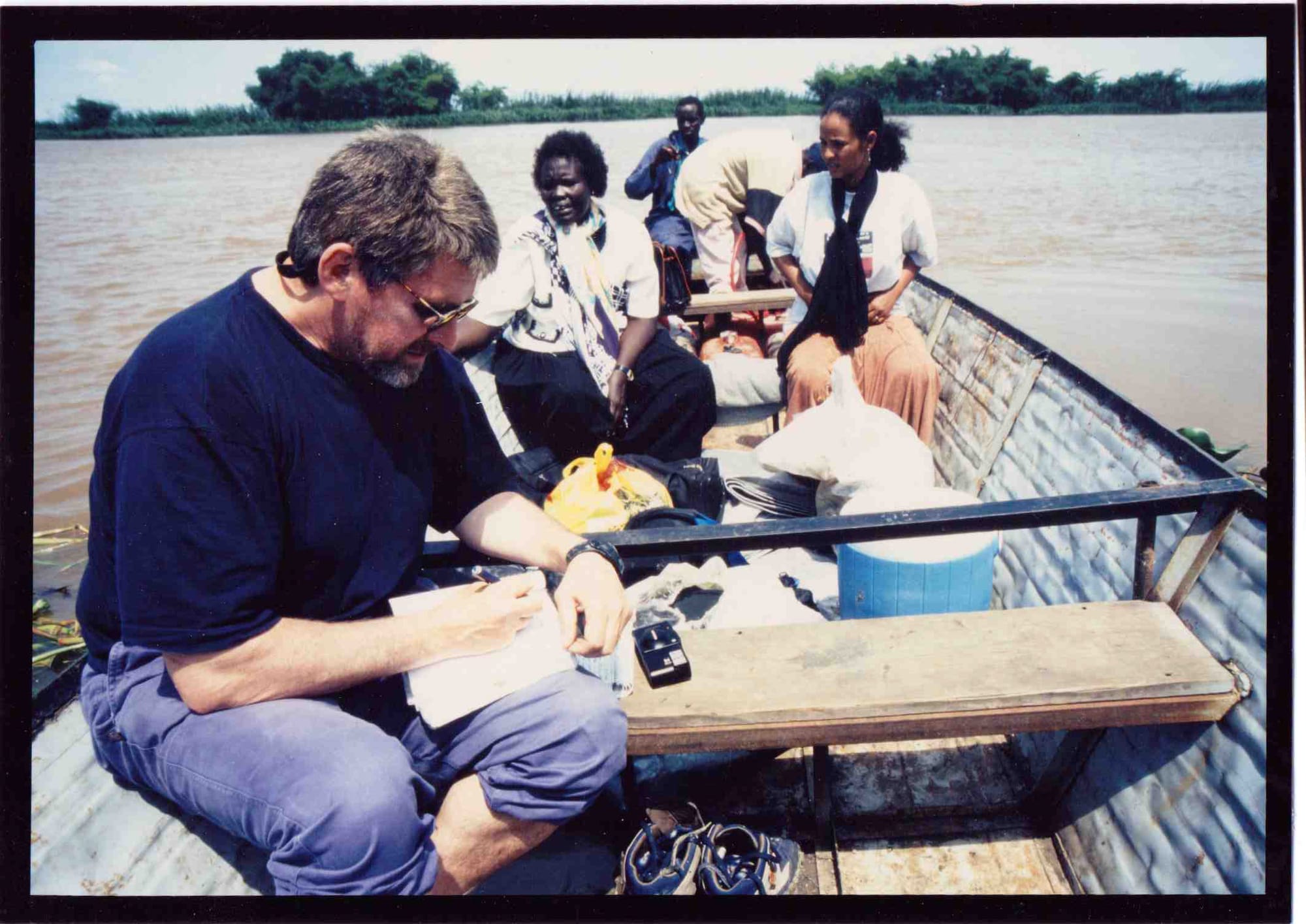

One of them was Band Aid, famous thanks to the charity single Do They Know It’s Christmas? released the previous December in response to the devastating famine in Ethiopia. The Band Aid foundation was extending its reach, and was about to start work in Sudan. At the same time, another international charity, Save the Children, got in touch with Rae, asking for his help. As Rae tells it, Band Aid were paying good money, but he wasn’t convinced by their operations. Save the Children were paying “pitiful money, but sounded like they had a fair idea what they were doing. So I agreed to go and work with them in Sudan for a year, setting up recovery for the aid convoys. It wasn’t so different to what I’d been doing in the Army, just on a much bigger scale.”

What followed his time in Sudan was a rather unexpected career change, as Rae then entered the humanitarian field, working initially with a Christian organisation called WorldVision, where he spent some time working with cross-border food convoys travelling between Zimbabwe and Mozambique. That’s where the problem of landmines became acute to him.

“It was a big issue, both attacks on convoys and trucks hitting mines, but it was one of those things where everybody said, ‘well, that’s military stuff’. Even if civilians got killed, it was military stuff so everybody thought the military should get rid of it. But that was never going to happen… in many places, the wars were over, but the landmines were left.”

Then, in late 1988, two things happened. While working with aid agencies in Pakistan dealing with refugees from the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, he met his future wife, Debbie Harrison, also working with a humanitarian group. And, hearing second and third hand about the problem of Soviet landmines blighting communities in Afghanistan, he decided he needed to see for himself.

Merseyside, Cumbria, Manchester. Despite Rae’s global travelling, often into the world’s most dangerous places, his heart remains in the North West. He lives in a modest terraced house in Carlisle. During our first interview by phone, he’s breaking off from decorating the living room. As we speak about his early years in Liverpool, his accent becomes pronouncedly more Scouse. When he set up MAG, he was working from a cottage in Cockermouth, Cumbria, where he’d gravitated to on his trips back to the UK while working for NGOs. As MAG grew, it needed a proper headquarters, somewhere with better transport links, with space to grow into an international organisation.

By the time MAG moved to Manchester in 1998 Rae had just stepped back from the day-to-day running of the empire he had built, but says Manchester was absolutely the right choice, a city he had a lot of affinity with. From clubbing there as a young man (“It had a different feel to Liverpool”) and spending time working closely with the Omega Research Foundation, which exposes human rights abuses across the world from its base on Beswick Street, he felt Manchester was MAG’s natural home. “It needed somewhere with good connections, it needed to be at the heart of a city. I couldn’t have gone to London, I’d have been broke within a week,” he says. “Manchester was the place MAG needed to be.” He set up MAG in 1989, and the driving force behind everything was his visit to Afghanistan the previous year.

“When we crossed from Pakistan into Afghanistan, it became absolutely clear to me,” says Rae. “I just thought, ‘what in God’s name is going on here?’ Mines were a massive issue, and nobody seemed to be talking about it. Villagers were walking single file on roads, walking across the top of ditches, avoiding huge areas of land, because the place was riddled with mines.” Visiting Afghanistan was prohibited because of the Soviet invasion, but through a Swedish NGO he made contact with a group of mujahideen fighters who had helped to liberate the Paktia Province from the Russian invaders. Rae had to disguise himself as a local tribesman, wearing traditional shalwar khamis and travelling, head down, with the feared mujahideen rebels, staying at safe houses along the way. He was taken to the town of Chamkani, where he saw devastation the war had caused — and was continuing to cause —with landmines. “It was totally ruined,” he says. “Agricultural land, orchards, all unusable. People couldn’t farm, their livelihoods had been taken away, even though fighting had stopped.”

When he returned to Pakistan, Rae brooded on what he’d seen. “I was just thinking, ‘how is this solvable?’ Nobody seemed to have an appetite for solving it. Then it struck me.”

People referred to minefields as though that’s what they naturally were, he realised. “(But) they weren’t minefields. They were fields that had been mined. That was what the formation of MAG was all about – reclaiming that land.” By the time he and Debbie got back to the UK some months later, Rae had a plan. They had no home due to working overseas for so many years, so rented a caravan in Cockermouth. While there, he applied his soldier’s mind to the problem – you go in, divide an area up into squares, and you work on each square until it’s declared clear. And you keep going. Now all he had to do was put the theory into practice. So in September 1991 Rae went to Turkey on a tourist visa and simply walked across the border to Kurdistan, where he carried out a survey of the land. He took his findings to the organisation Human Rights Watch (HRW), who agreed to publish it online in 1992, when the internet was in its infancy.

With the weight of a HRW report behind him, Rae was then able to begin aggressively marketing the idea of his nascent mine clearance organisation to various humanitarian organisations and global funding bodies. After knocking on enough doors, he eventually got through to the right people. One donor came to see Rae in the Cockermouth cottage. “I took him into the office and we had to climb over a filing cabinet. It was full of fax paper, stuff coming in overnight from Iraq, it was just crazy. He looked at me and said, ‘so, let’s get this straight. You’re running a de-mining operation in Iraq, and about to set one up in Cambodia from here?’ And immediately he wrote us a cheque.”

Rae ran MAG until 1996, when he decided it needed a board of trustees to head the ever-growing organisation. “It was a bit of a shock to some people, because this was my life’s work, but sometimes organisations can struggle under the weight of their founders. You have to almost be a dictator to get it going. But there comes a time when you need other people to decide where you go next, and I realised in 1996 MAG had reached that point.”

A year later, MAG was named co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, mainly for its founding role in the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, leading to the formation of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, also known as the Ottawa Treaty. That has been cemented this year by MAG winning the Hilton Humanitarian Prize. MAG’s current CEO is Darren Cormack, who said, “For 35 years, MAG has stood resolute in its mission to respond to the urgent needs of people in communities ravaged by conflict and in places still grappling with conflict’s legacy, long after the wars have ended.”

Though no longer has day-to-day involvement, Rae is almost a figurehead for the organisation, and goes into the Spinningfields offices quite regularly. “I’m totally overwhelmed by where MAG is now, it’s what I could never have dreamed of when I set it up, and that makes me very proud. And the Hilton Prize is fantastic, because funding isn’t easy to come by these days, so this will make a big difference.”

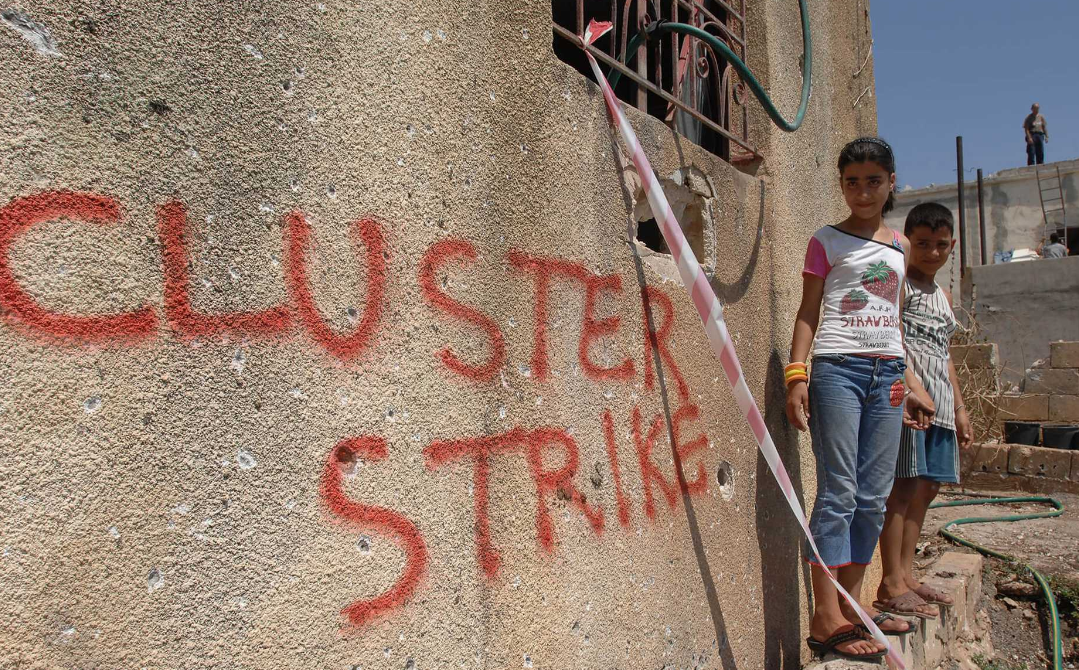

The problem is, of course, that for every acre of ground MAG clears and returns to the community in some country devastated by war long ago, across the world a fresh war — and a new wave of landmine contamination — is springing up. Gaza, Ukraine, Syria.

Recently, Rae was talking to Cormack, and mused that as exceptional a job as MAG was doing, it would be rather nice if it didn’t have to exist. “It seems like working ourselves out of business isn’t going to happen in the near future,” says Rae, soberly. “I don’t know what I thought 2025 would be like when I set up MAG, but it feels like the situation globally is just becoming worse. We are, I think, heading into bad times.” He pauses for a long moment, then brightens. “But MAG is doing an extraordinary job in the face of that, and as long as they’re needed they’ll be there. And that has to count for something, doesn't it?”

Enjoyed this edition? You can get two totally free editions of The Post every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

Comments

Latest

The lost department stores of Liverpool

From Simone's to Belzan: How a hospitality magnate seduced Liverpool's tastemakers

Last minute drama, local revamps and Liverpool Doc Club

Is Williamson Square Liverpool's own Times Square?

From Merseyside to the Middle East: Rae McGrath's mission to rid the world of landmines

Operating out of a cottage in Cumbria, one man's war to disarm military zones