When Keir came to town

England is warming to the Labour leader. Is Liverpool?

Jeremy Corbyn is telling me about his new placemat. He was given it by a supporter the other day, but he isn’t sure what John McDonnell will think. “It’s got Honorary Scouser written across it,” he says. “I love it, it’s great”.

We chat briefly at the end of a Stop the War Coalition meeting in the Racquet Club on Chapel Street, as his wife Laura diligently takes photo after photo. The Labour Party conference this week in Liverpool started with four words: “God Save the King”. An altogether different four words kicked off this meeting: “brothers, sisters, comrades, friends”. The meeting was a fringe event at the conference. It felt fringe with a capital F.

When Corbyn stands to speak the old chant rings out, the one I hadn’t heard live since a Libertines gig in Margate in 2017. A woman distributing leaflets to a human chain protest in Westminster makes a whooping sound only comparable to a Cherokee warrior’s war cry. I’m surprised nobody faints. When I ask the man himself how he expects the city to react to Sir Keir Starmer, he talks about dockers and trade unionists instead. “They have such a rich history in this city,” he says. And then, specifically of Liverpudlians: “They’ve got it right”.

Party conferences are strange things, kind of repetitive and grey. Robert Peston crouches in every doorway whispering into his phone, papers shuffle, lanyards swing like metronomes and never stop. I find myself perennially stooping to avoid being caught as an unwitting extra for GB News.

Starmer pops up here and there; cracking football jokes with Gary Neville (Neville advises he should play on the “centre-left of midfield”), cracking football jokes about Gary Neville (“we even managed to get a cheer for Gary Neville in Liverpool yesterday”) and even occasionally cracking jokes that make no mention of football or Gary Neville. He looks cock-a-hoop, king of the barbeque; ice cold beer in one hand, meat flipper in the other, everyone pretending to enjoy his terrible jokes because he’s the man doling out the chipolatas.

In his main speech, his line about rooting out anti-semitism gets a big cheer, which will be treated as a clear marker of how he has reshaped his party. At the traffic lights on the way home afterwards, I overhear two men in talking about Audrey White, the activist who caused Starmer embarrassment a few months back in Liverpool when she confronted him about writing for The Sun. They said she had been “show[ing] up” the party with her protests outside the conference arena and that Labour delegates were “shitting themselves”.

Earlier in the day, outside a meeting about Palestine, a young activist called Aaron is convinced he spotted Mick Lynch two nights ago in a kebab shop. It seems feasible enough, but his friend Esther isn’t convinced, given Aaron’s history of dubious politician sightings. Aaron concedes the point, telling us about the two hours he once spent excitedly telling a group chat that he was sat in the same train carriage heading to Newcastle as Corbyn, only to open up Twitter and see Corbyn addressing the House of Commons that afternoon.

In many ways this maybe-sighting reflects Lynch’s position at the outer edge of the four days’ proceedings. He’s the ghost at the banquet, addressing packed-out halls at fringe events with talk of billionaire bosses and the return of the working class, reigning supreme over an archipelago of rhetoric the Labour Party have long-since sailed away from. To be clear, most Starmer-supporting Labour councillors I ask don’t express any hostility towards Lynch, many are partially fond, but to Starmer’s detractors Lynch has everything the new left lacks.

I never catch Lynch himself, and have to make do with a man in a Mick Lynch hoodie. It features two images of the RMT boss, one suited and booted — professional, morning TV rounds Lynch; the other in a short-sleeve button up, arms crossed — feisty picket line Lynch, the father-in-law from hell. It reads: “Mick Lynch of the RMT, Simple as”. The man points down at the two images and says, “this is Mick when he’s making a dick out of Piers Morgan on the telly here, and this is Mick when standing up for workers here”. And what of Starmer? “He’s no Mick.”

This may be, but England, whether through lack of better choice or genuine embrace is — at least right now — starting to accept Starmer. The Labour Party, without question or doubt, has warmed to him, in a 14 standing ovations in 50 minutes kind of way. The question remains, though: has Liverpool?

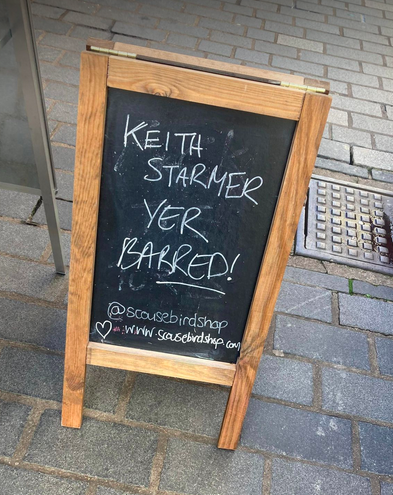

On the one hand, Merseyside has a handful of the sort of socialist MPs that are a rare breed in the rest of the country. It also boasts some of the most staunchly left-wing seats. Outside Scouse Bird on Tarleton Street a sign reads: “Keith Starmer…Yer barred”. For those not aware: Keith is the derogatory substitute for Keir used by his opponents who feel it befits his beige quality and lack of oomph. Mick Lynch hoodie man tells me the conference is only in Liverpool “in name”. On the surface at least, you’d assume, these views are vaguely representative of a lot of the city.

On the other hand that assumption could well be the kind of lazy exceptionalism that crops up so often when people talk about Liverpool. The reduction of a large and varied city into a single type: wily working class folk with big brash personalities who can see straight through corporate suits like Keir.

There are of course, more specific reasons he might not be greeted with open arms. The most powerful event of the conference I attend was Hillsborough Law Now. The details were almost too much to bear. As Charlotte Hennessy recounted a story she’d told many times, Nova Scotia on Liverpool’s waterfront iced over. She spoke of her Dad, Jimmy, whose death at Hillsborough in 1989 had been ruled as traumatic asphyxiation, a falsehood propagated for more than two decades.

Jimmy Hennessy hadn’t really been asphyxiated. The truth — two particularly loaded words in this case — discovered at the Judge Goldring inquests (2014-16) was that he’d been left in the corner of a gym unaided after being found alive by an officer on the pitch, then bundled into a bodybag by two other officers. When they opened the bag, he was hot, sweaty and had vomited. The actual cause of death was “inhalation of copious amounts of stomach content”.

Those officers then refused to give evidence on mental health grounds. “What about my mental health?” Charlotte asks, as several in the room tear up. The event (where speakers included Andy Burnham, Steve Rotheram, Maria Eagle MP and several representatives of groups campaigning for justice in regards to state cover-ups) was calling for the introduction of a “Hillsborough Law,” which would introduce measures to ensure public authorities actively cooperate with investigations. Labour have backed the introduction of the bill.

Pretty much at the same time, just a few hundred metres up the dock, Starmer was onstage with Neville talking about a recent trip to the Hillsborough Memorial at Anfield, where he was moved to read the names of several 14-year-olds, given his own son being 14. “My heart just stopped,” he said, before confirming that he would pass the law “as soon as we get into government”. The day later it was one of the first things he talked about in his conference address.

Towards the end of her speech, Charlotte reeled off a couple of tweets she had received during her years campaigning. “So tell me Charlotte was your Dad drunk when he contributed to his own death?” was one. “Has the Queen met the 97 ticketless scousers yet?” was the most recent. Of course, the history of Hillsborough slurs can be traced back to a newspaper whose name is itself a curse word in Merseyside, often asterisked, and in whose ink Starmer wrote an opinion piece last October. As a lady at the Stop the War Coalition event told me: “if their leader is a Sun columnist then no one in this city should consider voting for Labour”.

Some of Liverpool’s Labour representatives have an uneasy relationship with Starmer. Just before the conference kicked off, Riverside MP Kim Johnson told a crowd of striking dockers that his failure to aptly back them indicated a lack of “balls”. Talking to me a few days later though, she says that the media are too “obsessed by the left” and that it’s time for the party to get behind the leader. What about those dockers? “I’m sure the dockers or any picket line would welcome him coming down and showing solidarity” is the diplomatic reply.

The potential de-selection of West Derby MP Ian Byrne, who is extremely popular on Merseyside, was seen by many as the Starmerite right flexing its muscles. And Hillsborough, naturally, is the big one. However, Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram — who said last year he thought Starmer “regrets” writing in The Sun — used his own address to the main conference to suggest it was time for “naysayers” to get behind their ascendent leader.

After the event, Byrne tells me that “this event isn’t about Keir Starmer,” but adds he had felt “betrayed” at the time and told the leader personally. “There’s never any excuse for anyone in our party to be going near that rag,” he says. Starmer, no doubt, would argue that in order to even pass a Hillsborough Law in the first place you’d need power, and if writing for The Sun tips the balance in his favour so be it. But for the likes of Byrne, and of course many others, this is the one line that you can never cross.

Bill Esterson, MP for Sefton and shadow cabinet member for International Trade, tells me he spent “a long train journey” with Starmer from Liverpool to London after the Sun piece. Through the Hillsborough law, Esterson believes, the leader is “making up for it in his way”. Part of his effectiveness when he was working as Director of Public Prosecutions, Esterson says, was “recognising when he might’ve made a mistake”. Is it a forgivable one? “For some people it will be very hard to get past,” he replies. “That’s completely understandable. But the Hillsborough law should be a huge step forward”.

Esterson talks about his own life experiences — power cuts in the 70s as a child, the IMF bailout in 1976, the shrinking of the state under Thatcher — and how they’re all coming true once again. The priority has to be ushering in a Labour government. “We can win now,” he continues. “Before it was more wishful thinking.”

There's confidence in his voice, no shock there. Labour are 17 points up in the polls. The day later it’s 33. Absurd seat projections are doing the rounds on Twitter; 61 seats for the Tories, almost 500 for Labour. I meet a party member called Tom from Dingle in the exhibition hall. We stand next to an assisted dying stall and I put to him some of the criticisms I’ve heard over the last few days; all the expensive blue suits, the neatly parted hair, the stalls for FTSE 100 firms, the Betting and Gambling Council-funded Daily Mirror party where Wes Streeting crowbars Starmer’s name into Take That lyrics at the karaoke mic. Is it very Liverpool?

“Karaoke is, I guess,” he jokes. “To be honest I get kind of bored of the whole, Liverpool thinks this or Liverpool thinks that. Liverpool isn’t one person, is it?” Tom thinks that whilst most of Liverpool want a Labour government, it’s unlikely that a lot of people care whether it’s Corbyn or Starmer. “They just want Labour,” he says. His friend butts in. “Better the latter though”. More so than Tom, he has the eyes of a true believer, sated by the sacraments of the holy centre ground: videos of Tony Blair and fiscal prudence.

Later in the day, a delegate from a Liverpool CLP tells me that the best thing she’s done over the conference so far is go down to docks and support the strikers. Mick Lynch was there, and this is a confirmable Lynch sighting: the flesh and bone real life Lynch, not mystery kebab shop Lynch. “I’d rather be there than sitting at the back of a conference hall because the party is embarrassed by anyone from the city they’re standing in,” she says.

She tells me about the atmosphere down at the dock — “electric” — and uses the word solidarity several times. What about the conference? “I’ll still probably vote for them but they aren’t offering anything to get excited about,” she says. “And they treat us like a bunch of fringe lunatics, when really all we wanted was people who were less well off to get a better chance in life.” She looks melancholy. “We’ll come again, there’s plenty of us around here”.

Comments

Latest

Trust in vaccines has fallen post-COVID. Now Knowsley has a measles outbreak

A Liverpool developer became a Dubai crypto kingpin. Now he’s accused of defrauding investors out of $400 million

Is Liverpool on track for net zero by 2030?

Just what is a “public space” in Liverpool?

When Keir came to town

England is warming to the Labour leader. Is Liverpool?