What’s past is prologue: How Shakespeare came to Prescot

The marking of an ancient connection to the Bard is bringing huge investment and attention to this post-industrial town - but how will a theatre impact life here?

Dear readers — before we get to our weekend read, here are a few members-only stories we’ve published in the past week. If you haven’t joined up as a member yet, you can do so by clicking here. You’ll get exclusive members’ stories every week, and you’ll be supporting the renaissance of high-quality journalism in this region.

- The story behind Labour's suspension of a Sefton council ward: 'It’s nothing to do with me,' says the councillor at the centre of a local intrigue. Harry Shukman speaks to a dozen sources to find out more.

- The new social media accounts that track the movements of Merseyside Police: Mollie Simpson speaks to the people who warn Instagram users about the presence of police vans and local cops.

- Is Liverpool Britain's TikTok capital? Alice Porter meet the young people making huge waves on Gen Z's favourite app. “I think one of the biggest impacts TikTok has had on people my age is making a million seem like such an achievable number,” one of the influencers tells her.

Here’s an extract from Harry’s story about the Ford ward in Sefton:

Liz Dowd, one of Ford’s Labour councillors, is up for election this May, which means any attempts to deselect her as a candidate would have needed to happen this month. We understand that the shortlisting process was supposed to take place on December 8th, followed by the formal selection on the 15th. But on December 7th, one day before the shortlisting, the ward’s secretary received an email from Andy Smith, the Labour Party’s Head of Regional Governance and Local Government North. “There have been a series of complaints into [sic] regard to the running of Ford Ward, and the activities of Ford Ward members,” the email began.

By Robin Brown

One night in the early 2000s, Professor Elspeth Graham mentioned to a friend that she was heading to Prescot. “They said ‘be careful, it’s quite a tough place’,” she recalls. “Aside from being completely untrue, I thought ‘why should people have to live somewhere that has a reputation for being a rubbish place?’ I wanted kids to grow up thinking ‘I’m from Prescot — and that’s a really special place’.”

Elspeth, a lecturer in literature and cultural history at Liverpool John Moores University, began to consider the exchange and ponder what could put the town back on the map. “Prescot has a unique history, which is why it’s possible to do this project in Prescot.”

The project is the imminent arrival of the £27m Shakespeare North Playhouse, a reimagining of a 17th-century playhouse that existed for a short time in Prescot — and what could be one of the more remarkable social engineering projects of recent times. Quite what the Bard’s connection to Prescot was is a matter of some debate, but that hasn’t stopped the Shakespeare Trust from building a new cockpit-style theatre in the town, due to open in 2022.

The Playhouse will feature a timber-framed theatre that reflects the original’s 1693 design — inside, if not externally. However, no one knows what the original looked like, so the Playhouse will be built to the designs of an Inigo Jones-built court theatre in London, drawn up in 1629. It will incorporate an outdoor performance garden, exhibition and visitor centre and educational facilities; it’s estimated that the theatre will generate 100,000 new visitors and £5.3m annually — and it’s already brought more public and private money to Prescot.

Max Steinberg, who knows a thing or two about theatre, says “This is not Field of Dreams, a case of build it and they will come; we are building and they have already come.” Dame Judi Dench — a trustee — says it will be “much more than ‘just’ a theatre.”

Yet the chances are it might never have happened, were it not for a casual conversation between Elspeth and her colleague, Doctor Matt Jordan, in 2003, in the wake of Liverpool winning its Capital of Culture 2008 bid. “Matt said ‘you know that there was an Elizabethan Playhouse in Prescot — well, how would it be if our contribution to the Capital of Culture was to rebuild the Playhouse?’ And I said ‘why would we want to do that?’, but the idea grew on me.”

Initial scepticism gave way to a gradual belief that bringing an Elizabethan theatre back to Prescot was possible; that the unlikely nature of the project made it more viable than if it had been in the centre of Liverpool: “There’s a sense of it being magical.” She argues that part of that magic derives from an unknown history, “a sort of synthesis of all of these genuine things, which are lost in time.”

For a town that was at the heart of the UK’s watch and clock industry, time has not been kind to Prescot. Just a few years ago the town was, by the admission of many Prescotians, “dead” — even the Playhouse website’s own literature describes the town, euphemistically, as “somewhat sleepy.” After the industries of clocks and cables disappeared, salvation was promised in the form of a giant Tesco and a retail park on the site of the British Insulated Callender's Cables site (Prescot was one of the first towns in the UK to get electric street lighting as a result of the business and the football team, Prescot Cables, still bears the name) — which served to draw much of the remaining life from the historic centre of what was once one of the largest market towns in the North West.

Even the often-beautiful Eccleston Street — bookended by a Grade I listed 17th-century church and a flatiron building, boasting the UK's second narrowest street and featuring a burgeoning range of food and drink offerings — still bears the scars, despite recent investment to improve public realm. Shakespeare quotes now adorn the pavement: “I wasted time and now time doth waste me,” seems like a provocative choice. The street’s shopping centre would be rejected as too bleak by a location scout for a zombie film (its owners, Geraud, were contacted for this article but did not respond). Most of its units are deserted and the escalators didn’t work for months in 2021, though the Prescot Museum has set up temporary home in the one-stop shop, where you can order a book from the library, pay your council tax and admire the Town Chest.

“Only a third of the collection is here,” confides the librarian sadly. “The rest is in storage.”

200 yards away, outside the Playhouse, Alan is taking photos. He’s been recording every stage of the building’s development and has booked onto a tour of the building. He used to take photos of aeroplanes around the North West but stopped when Covid struck. Alan doesn’t seem like a natural theatre-goer, but he’s keen to try something new when the theatre opens. “Everything's changing already — new bars, cafes, restaurants,” he enthuses.

Alan is surely talking about Pinion, a bistro opened by Gary Usher — 2021’s Restaurateur of the Year — in a former bookies on Eccleston Street. Usher opened Pinion, named as an acknowledgment of the town’s watch and clockmaking heritage in 2018, following a crowdfunder to raise £50,000. He reached the target in under an hour.

“My first impressions were ‘Jesus, this place is quiet’ and ‘Christ, this would be a challenge’,'' he laughs, when asked what he first made of Prescot. He readily admits that the new theatre played into his decision to open in the town, but was still cautious.

“When I look at footfall and what we need to do to break even, to be honest it’s a ridiculous plan, but I like it. I like the people, I like the humility there. Prescot has seen some really shitty times recently but it’s not stopping people getting behind it.”

What Usher wants Pinion to be is chimes with the modus operandi of the Playhouse — an intention to bring in people to Prescot, but not at the expense of locals.

“It’s not about destination dining — it's not for people to travel 50 miles to eat there. It’s about a place where customers know the staff — it’s a local restaurant for local people…” he laughs at the unintentional League Of Gentlemen reference. “A little hub for the community — that's hopefully what Pinion is.”

While many agree that Pinion was a landmark moment for Prescot, Usher wasn’t the first to notice that the town had… something.

Albion is owned by Nina Halliwell, who hasn’t looked back since opening in Prescot in 2015. She’s one of a new generation of businesses in the town centre — alongside a doughnuttery, a pizzeria and several new bars — who have helped form a critical mass here. In the bustling kitchen, soundtracked by Noughties pop-punk and wearing a headband, Nina evokes a modern WWII We Can Do It! poster.

“It was only when I came back that I realised all the history connected with the place — I thought ‘this could be like Lark Lane!’ It was quite dead here when I opened but you could see the potential all the time. Things were going in the right direction. But it’s not like everything is going to be amazing once the theatre is here because there’s a lot that needs doing with the town centre. “

Nina worries about the chilling effect of Covid and the relative lack of a daytime economy in Prescot — and rolls her eyes at the mention of the nearby shopping centre (“it needs knocking down,” she declares).

“What we don’t want is people coming to the theatre and then leaving. Perhaps they’ll come here for afternoon tea, then go for the pre-theatre menu at Pinion. But there needs to be a critical mass. We need more daytime; we need more retail. You can’t just have nighttime attractions — you need a good mix.”

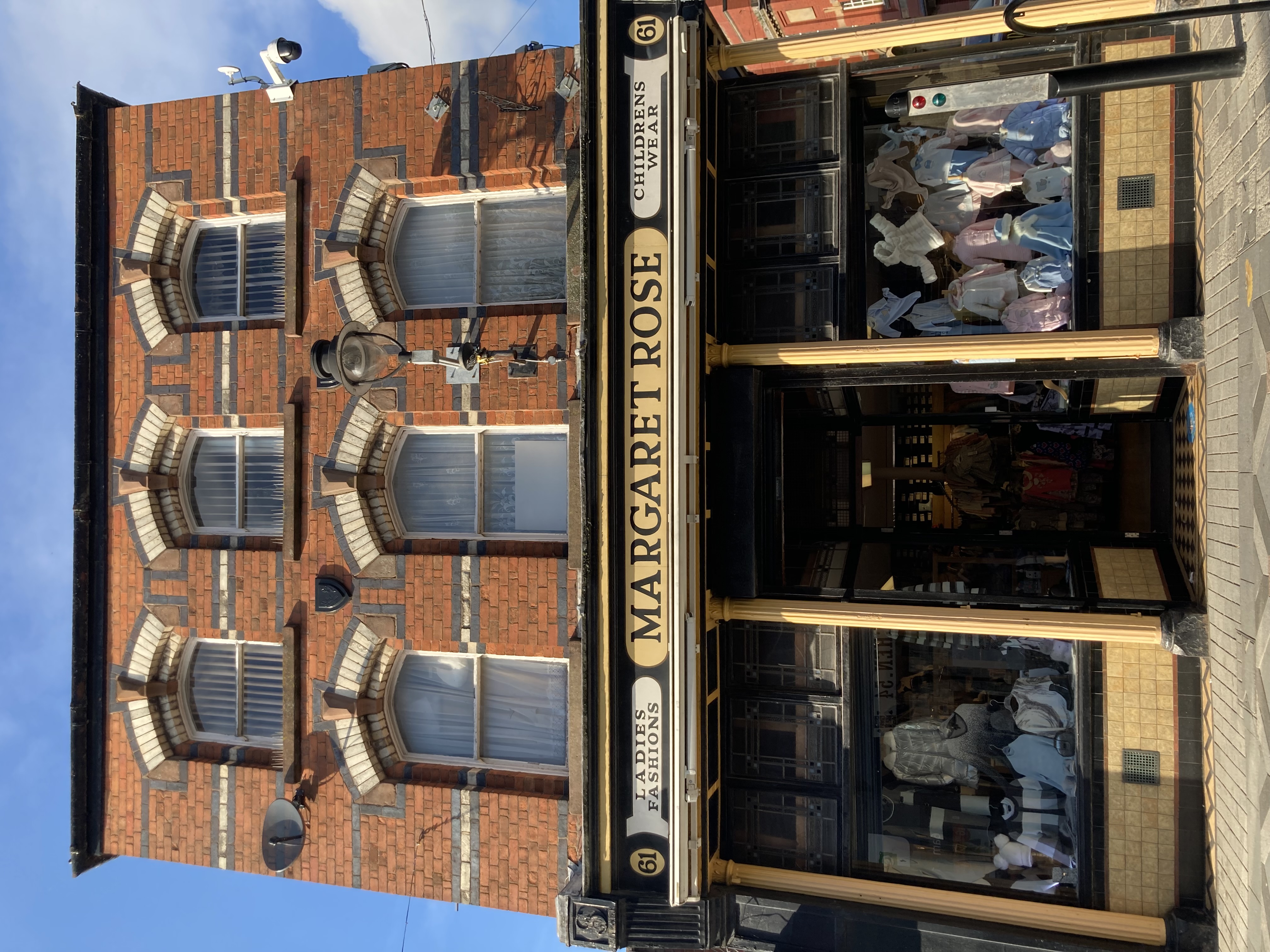

Concerns over the daytime economy in Prescot are echoed by Louise Gillespie, who runs women’s fashion shop Jessie & Co. Born in Huyton and resident in Prescot since buying a house nearby 30 years ago, Louise can still remember when the town was surrounded by fields filled with sheep and cattle.

“You will get naysayers but to have that connection to Shakespeare here in Prescot… how can it not be a good thing? Don’t knock it — we’re getting it! But Prescot needs a lot of work if it’s going to be somewhere we’re welcoming people to.”

This is, perhaps, the nub of locals’ concerns about the theatre. Not that it won’t be a good thing in and of itself. But perhaps the question is this: can it really be a driver for a wider regeneration of a stereotypical left-behind town?

Ask Prescotians what they want and they mention a swimming pool, an ice rink, more parking. Within months in 2011, Prescot lost its police station and swimming baths. When the New York Times visited Prescot in 2018, the town amounted to a “tour of the casualties of Britain’s age of austerity.” But if recent times haven’t been kind, residents are hopeful that what is lurking in Prescot’s past could be its salvation.

“I’ve always had a love and a passion for Prescot,” adds Louise. “The history, the geography — there’s so much character to it.” The town’s history has recently been detailed in a series of gleaming red plaques detailing the 16th-Century timber frames of some Prescot buildings, 28-inch-wide Stone Street and the site of the original Prescot Playhouse. The Lord Strange pub has gone one better — a huge mural of the Bard now adorns the side of the pub. The Bard, serving local real ale and cask beers, describes itself as a ‘Shakespeare-themed micropub’.

While details as to William Shakespeare’s direct involvement in Prescot are fuzzy, everyone agrees there was the only purpose-built Elizabethan theatre outside London and it performed some early plays.

Theatregoers to the new Playhouse will experience music, comedy, musicals, pantomimes and more ‘in-the-round’ — the stage surrounded on all sides by the audience for much of the year. And, of course, Shakespearean theatre. But not all the time.

“It’s not all about Shakespeare,” laughs Gaynor LaRocca.

Gaynor is CEO and Artistic Director Imaginarium Theatre, an associate company company that is driving the community engagement for Shakespeare North. She also co-owns the Imaginarium Bistro, built on the site of an old toilet block.

Discussing the Playhouse and her own experiences of producing theatre in Prescot and Knowsley over the last two decades, she is surrounded by images from previous productions staged at Prescot Woodland Theatre, behind the Parish Church’s vicarage.

She is at pains to make it clear that the Playhouse won’t be a beamed-in London project — and her appointment is proof. She points to pictures on the wall showing local performers in recent productions as proof of community buy-in. Her husband Francesco, whose father ran Prescot's first Italian restaurant, is pictured as a ‘steampunk Long John Silver’. “It’s a huge community army that makes one show,” says Gaynor. And there are clear steps that demonstrate that the new theatre will be a true Prescot Playhouse.

“The aspiration is that next year every schoolchild from across Knowsley will get a chance to stand on the Playhouse stage,” she adds. “The fact that we’re the key associate and a community arts organisation is a huge part of [Shakespeare North’s] commitment to what the theatre is going to be.”

Clearly the arrival of the Playhouse will do wonders for Prescot’s cultural landscape, but Gaynor — who was part of Creative Communities team for Liverpool Capital of Culture — says the economic benefits of culture are well-understood. “Culture is a huge vehicle for regeneration. It attracts the nighttime economy, footfall through tourism and local visitors. There are new businesses — and existing business is reinvesting and jumping on the back of this journey we’re going on.”

She points to the example of Stratford-Upon-Avon. “It’s a stunning place and it’s always busy, but before the Royal Shakespeare Theatre came it was a dying town, the economy was on its knees,” she says. “Now it’s insane how successful it is and how beautiful it is.”

However, as part of the Playhouse’s community outreach, Gaynor is well aware that there are still hearts and minds to be won over.

“It’s hard sometimes to convince people it’s not a white elephant,” she admits. “If you’re in a small town and you’ve watched it die and your baths have been closed…” she tails off, “but what’s magical is there’s a real identity here. They are Prescotians, that’s a thing. The town is very precious to them — and the sense of community.”

The theatre may be the jewel in the crown, but Prescot hasn’t put all its eggs in one basket . Alongside the Playhouse will be a rejuvenated cinema — the Prescot Palace — and more cash for Cockpit House, the former museum, which is to be renovated to create a makerspace, house Imaginarium Theatre and provide tourist information.

The two developments are landmarks of the High Street Heritage Action Zone (HSHAZ) project, jointly funded by Knowsley Council and Historic England, and designed to bring older buildings back to life. There’s a sense that people in Prescot — as well as jobs and investment — do want a high street to be proud of.

“I think a good way to regenerate a high street is just by taking them back to what they were before,” says Gary Usher. “Sounds ridiculous but if you look at the way bread has boomed — real, proper bread baked in a bakery in the morning, it’s come back and with that so will the butchers, fishmongers and greengrocers.

“All that has closed down and fucking Tesco’s have taken over the world and big soulless crap retail parks, where people go there because they can park their cars. But I think everyone is sick of it now and I think people are starting to say ‘those retail parks are shit, I don’t want to go in Caffè Nero and sit in the Next cafe or go to these generic corporate shops’. Actually they want a bit of soul, character in their lives.”

Usher has a casual zeal for food — and for Prescot. And to listen to Gaynor it’s easy to imagine how she’s managed to convince so many people initially wary of promises of Prescot’s rebirth — and how she manages to convince so many sceptics to get up on stage and give the public their finest Bottom.

Gaynor is quick to credit Elspeth Graham with the original idea, but there’s a cast of dozens behind bringing the Playhouse to fruition. Patrick Stewart, Helen Mirren, Lady Anne Dodd, and Paul McCartney have all lent their voices — and cash in the case of Doddy, a genuine Shakespeare buff often seen at the Liverpool Playhouse’s Shakespearean productions — to the project. Frank Cotterell-Boyce is heading up As You Write It, a competition for young people to write their own play at the Playhouse.

But behind the scenes gives a fuller picture. Of grant applications, chance meetings and the hard slog of academics, architects and public servants over 20 years, whose names might get forgotten in the blaze of the Playhouse’s opening. Soon all of the myriad of those things will culminate in a celebration of the theatre — and Prescot.

Between the end of Eccleston Street, the Parish Church and the site of the new Playhouse is the old market square. Adjoined now by the Imaginarium Bistro, there’s a large roundhouse, for which local artists fashioned a wooden cabin. Over Christmas Father Christmas can be found inside entertaining families. And, during Winter, a story catching event there will capture the memories, hopes and dreams of Prescotians using parchment and quills. Next year the stories will be reinterpreted through media, dance and performance. ‘Magic’ is a word on the lips of many who are invested with both town and theatre; people who invoke something enigmatic to describe the synthesis between the two. It’s hard to think of a better example.

Elspeth Graham gives the impression that she still won’t believe it when she sees it. “Brilliant, but a little bonkers,” is her assessment, nearly 20 years on from that original conversation with Matt Jordan. When asked if there’s a line or two from Shakespeare that reflects her feelings about the opening of the Playhouse and its place in Prescot, she plumps for something from Love’s Labour’s Lost, which opens with the King of Navarre stating his intention to create a society that should be ‘the wonder of the world’.

Our court shall be a little Academe,

Still and contemplative in living art.

Intimidation? Harassment? The story behind Labour's suspension of a Sefton council ward.

— The Post (@liverpoolpost) 7:26 PM ∙ Dec 18, 2021

@HShukman spoke to a dozen local politicians and party members to understand what’s going on. “It’s a fucking mess,” is how one senior Labour source puts it.

Comments

Latest

Between Labour, Reform and Jeremy Corbyn, what does Liverpool’s electoral future look like?

Pete Burns wasn’t nice, kind, or fair. But he was unforgettable

Can we revive Liverpool’s high streets?

Ghosts, gangsters and giving Liscard a chance

What’s past is prologue: How Shakespeare came to Prescot

The marking of an ancient connection to the Bard is bringing huge investment and attention to this post-industrial town - but how will a theatre impact life here?