Two Russian sailors walk into a bar — the rest is cinema history

‘Letter to Brezhnev’ is Liverpool’s greatest rom-com

By Jack Walton and Sophie Atkinson

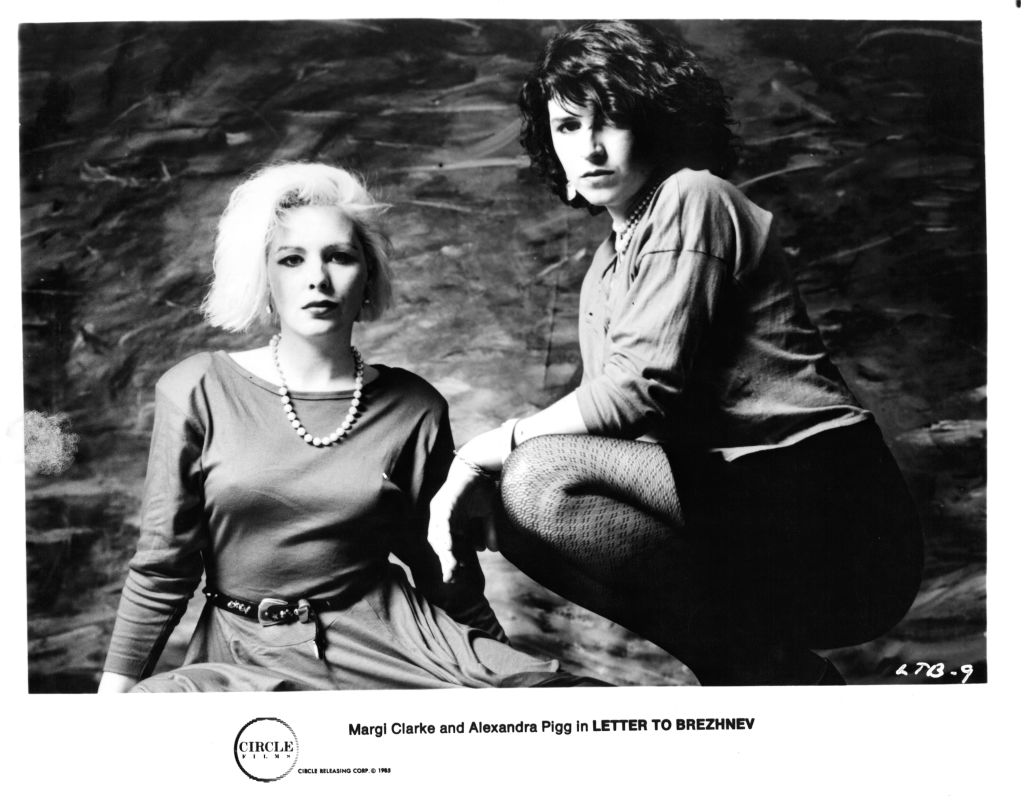

Meet Elaine and Teresa. Elaine is dark-haired, romantic, a little bit dreamy. She exists in the subjunctive: if I were somewhere else, I might be happy. Teresa is her polar opposite: crowned with a shock of blonde hair, she doesn't need to dream about an alternative reality. She’s perfectly content in this one, moving from one pleasure to the next: a cigarette, a stiff drink, a decent one night stand. Ditching the others, they head out on a night out, where meeting two Russian sailors will change the course of their lives.

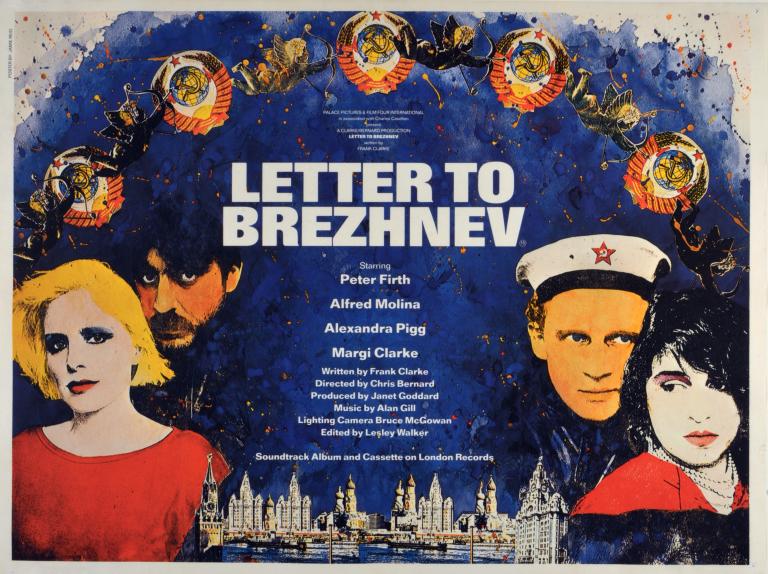

If you’ve seen it, you’ll already know what I’m talking about: the leads of 1985’s greatest romantic comedy, Letter to Brezhnev. It’s a rare film that ties together a chicken factory in Kirkby with the former leader of the Soviet Union, Leonid Brezhnev, and a downtown disco, all shot on the streets of Liverpool. But rarer still is the story of how that story got made.

It’s a remarkable thing to shoot such a film with an effectively unpaid cast and crew — living in squats, and for the finished product to soar to the top of the UK box office. And even more so for such a project to be helmed by a first-time director. But for one thing, cream always rises. And for another, Chris Bernard’s mother always thought he’d grow up to be a successful filmmaker. It was — in her words — “noble shit”.

Bernard is as garrulous, warm and unfiltered as the characters in the film. We’re in his living room — I’m tucked into the crease of the deepest sofa I’ve ever sat on — to talk about how Letter to Brezhnev was made on a shoestring and became an instant classic. But Bernard isn’t the easiest man to keep on topic. His speech is littered with whatever the verbal equivalent of footnotes are, dropping random details into sentences (like the time future Doctor Who star Janet Fielding pinched his boyfriend) and frankly, it can be a little hard to follow. But who could blame a person who has led such a rich and eventful life? Plus, to truly understand the culture from which Letter to Brezhnev arose, you have to go a little back on yourself. You have to rewind to 1976.

Back then, Bernard was in his late teens attending a “shitty little college”. He was skinny and arty, and went round with an 8mm camera shooting bits and pieces. Not Super 8 — or anything flash. Standard 8. The wind up sort. He’d been a member of the Liverpool Youth Theatre Film Club, which had piqued his interest in filmmaking, when a mate mentioned a production he was involved in with Ken Campbell, the legendary experimental director of fringe theatre. Campbell needed someone to help out with the props. Bernard was keen to help.

So off he went to a warehouse on Matthew Street: a precursor of sorts to Manchester’s Afflecks Palace, but “mintier” (read: grimier). On the ground floor there was a kind of hippie bazaar. On the first floor, a group of actors, directors and crew were in the process of forming the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool. The play they were making: Illuminatus! — a voyage of drugs, sex and magic into the Deep Pool of conspiracy theorism.

Bill Drummond, a Scotsman, was designing the show down in the basement. He was tough-looking but artisan, boilersuits and boots, and would later famously burn £1 million (or did he?) as part of a performance art piece in 1994, as well as playing in the iconic electronic band The KLF. But that’s another story. Drummond took Bernard under his wing and tasked him with rounding up props for the performance. He’d stepped into a brave new world.

But before we go on: the names that crop up in relation to the Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool isn’t some endurance act of name-dropping on Bernard’s part. You have to understand, this was merely the sprawling scope of talent that converged in a small Liverpudlian theatre in 1976. One top of Campbell and Drummond; Jim Broadbent (Academy Award-winner), Prunella Gee (who had a key role alongside Sidney Poitier and Michael Caine in The Wilby Conspiracy the year prior), David Rappaport (an actor who worked in over a dozen films) and Bill Nighy (Academy Award-nominated, BAFTA winner). There are others — you get the idea.

Anyway, Bernard was sent out on a mission for an assortment of props at the behest of Drummond. He had no money, so tasked a group of boys in his cousin’s pub to help him out, and asked his mother for the family’s carpet since Drummond needed one. She was looking for an excuse to get a new one and rolled it up and handed it over. He also went off with the family’s living room wallpaper. Drummond was impressed.

Illuminatus! was a grand success — although they never took more than £1.50 for a ticket and the backstage toilet was shared by 27 actors (it was Bernard’s job to clean it), the show caught the attention of the right people. Its full run was an astonishing 22 hours (Campell was indeed as experimental as his reputation suggested), but it was so well acclaimed it was picked up by the National Theatre in London.

They took it there, and later to Amsterdam, Frankfurt and back to London at the famous Roundhouse Theatre. Bernard found himself rapidly scaling the food chain and soon wound up in the role of company manager. It would take another decade for Brezhnev to come about, but it was those days in late 70s, surrounded by magisterial talents — and somewhat squalid conditions — on Matthew Street, that its groundworks were laid.

A few years later Bernard had opened a Community Theatre resource, making props (like paper mache greek helmets, fairground horses and the likes) and helping put on plays. Margi Clarke — a local poet and actress (and a “match for Monroe” in Bernard’s eyes) was due to perform at the end of one of the shows one night. But Clarke didn’t show.

That is, until Bernard was sitting with his mate in the bar afterwards having a drink. He heard a ran-tan-tan on the window. There she was: auburn-ginger hair up in a pile of curls, surrounded by a small coterie including the iconic feminist film-maker, poet and activist Sandi Hughes, and her brother, Frank Clarke.

The creative partnership between Frank and Bernard would go on to form the backbone of Brezhnev. Frank was the writer, and in Bernard’s eyes the real genius. He’d done a lot of writing on Brookside, Phil Redmond’s classic soap filmed in Croxteth. For a while after they met Bernard dabbled in similar work. But in Frank’s head an idea was beginning to form. Its seed had been sown when he’d heard his sister Margi singing a little song that was part of a pilot for a TV show she was working on with Carol Ann-Duffy, the future Poet Laureate. It was a pastiche of Betty Davies’ character Baby Jane doing I’m sending a letter to Daddy. Her version: I’m sending a letter to Brezhnev.

Like Bernard, Frank was gay. They got a flat together, and the question of whether they were lovers is one that has always lingered. “We never were though,” he says. “That’s what made our creative relationship and our relationship as a whole powerful — there was no ego between us”.

Brezhnev began to take shape in Frank’s mind. And then on paper. The script — about two Scouse girls who “cop off” (a turn of phrase beloved of both the film and Bernard’s own speech) with two Russian sailors who are docked on shore in Liverpool, came together quickly. Teresa just wants a night of fun, Elaine is looking for romance and falls for Peter, who later has to leave to return to Russia. It was in many ways based on their own ideas of romance, but actually writing about two men who fall in love didn’t really feel like an option. And besides, Frank wanted to write his sister into the lead. It got sent around to a handful of film people, but despite superlative feedback from a London-based TV company (“this is one of the best things we’ve ever read” they wrote back) they soon decided it’d have better luck as a stage play.

A cast of unknowns was assembled, Margi the only ‘known’, and they had success performing Brezhnev at the Unity Theatre. But all the while the ambition of making an actual film never left them. If they were to do it though, they’d need to do it themselves. At the time there was a whole oeuvre of film-makers working in a kind of guerilla-style, like Derek Jarman, scraping together whatever resources they could and heading out with a camera. So in March 1984 Frank travelled to the Isle of Man to meet Charlie Castleton, heir to the Baxi boilers empire and brother of a friend of his. Castleton offered £30,000 to get the project underway. Joyous, Frank returned to England, caught a cab to Sefton Park where Bernard was staying, burst into his flat and offered him the role of director.

They began to assemble a crew. Bernard’s old mate Bruce McGowan brought in as cinematographer, old friends from the Science Fiction theatre got the call. Ken Campbell to play a seedy journalist. Neil Cunningham to play a man at the foreign office. Peter Firth — who went on to earn an Oscar nomination — came in as Elaine’s Russian love interest Peter as his girlfriend at the time wanted to try her hand at acting and had come up to Liverpool. “Peter looked at how we were living and was horrified,” Bernard says. “He saw me shaving with an old razor that hacked my face off”. It began to snowball though. Alfred Molina, another actor who would go on to win endless awards, joined as Sergei.

Filming in such a way, on such a shoestring, naturally means occasional compromise. But that was all part of it. Birkenhead had to stand in for Moscow in one scene, for example. In another, set in the State Club, where Teresa and Elaine meet the two Russians for the first time, a dearth of extras meant having to get the same people to change jackets as they filmed back and forth across the club. On Youtube, one commenter asks why — in the same scene when Teresa and Elaine chat in the toilet — “the water in the toilet is still clear [afterwards]”. Bernard says he regrets not chucking in a tea bag before rolling the cameras.

The money they’d raised soon disappeared. One of the cameras — previously used on Peter Greenaway’s The Draughtsman's Contract — jammed, but they were able to convince the insurance company to pay up despite having met virtually none of the conditions of their insurance deal. But the more they filmed, in the bars, hotels and out on the streets of Liverpool, scenes of sex, booze and profanity, the more it became clear they were onto something.

The plan was to get the film made, then scrape some more money to get a print of it and show it at some festivals. They were ambitious — but not pie in the sky. Paul Lister, a press guy they’d hired after working with him on Brookside, had other ideas. “He got out there and was battering it home,” Bernard says. Out of nowhere, a whole glamorous world of reviewers were interested — from the LA Times’s legendary Roger Ebert, to Newsnight's arts correspondent (and later Dame) Joan Bakewell, who paid them a visit on set.

The buzz sparked interest from representatives of Channel 4 and Palace Pictures, who also paid them a visit. They all crouched into Bernard’s living room as he projected what they’d shot so far onto a draped sheet. On the train home from Liverpool to London the representatives of the two companies were fighting over who would get the film. They struck a deal that they both would: suddenly they had proper funding.

In total, filming took just three weeks. All the while they’d lived in a squat while they rehearsed, various crew members nipping off to pinch food from Tesco that Margi Clarke — “a great cook” — would whip up into something nice. Everyone got a fiver a day, mostly to ensure they could jump a cab to get to set at short notice if need be. Peter Firth was offered £1000 as a goodwill payment. He turned it down and told them to use it for the film instead.

When the film opened, it went straight to the top of the UK Box Office. Not bad considering the world premiere had been in the Knowsley Council offices. “The movie doesn't have big stars, it doesn't have an earthshaking story to tell and it's not ashamed of its Liverpool accents; in fact, it's proud of them,” wrote Roger Ebert in the Chicago Sun-Times.

Liverpool nowadays is the most filmed city in England outside of London. Brezhnev had a pretty big hand in that. The British Film Institute would later say that it “has done more than perhaps any other film before or since in putting Liverpool on the cinematic map”. Not that it was ever gushingly romantic about the streets that made up its set. “Just look at this city,” says a joint-smoking taxi-driver early in the film as he weaves through Liverpool, “whoever did the planning for all this wants his balls roasted”.

Why did it chime? A long pause. “Authoritative voice. Authoritative voice”. It didn’t matter that they were operating out of a room with a cistern on top of a beer crate in the toilet, what mattered was that the film spoke in a language people were craving to hear. It was romantic, and sentimental in parts, but in equal parts brash, fierce and without filter on the Scouseness. For such a film to have such an impact was a truly rare thing.

It’s tempting to see this as Bernard’s story, a wide-eyed teenager, an innocent “St Christopher” as he terms it, stumbling upon a bohemian den of artistic genius and grime in equal measure, and finding himself among it. You might call it cinematic. A little Hollywood. But he would never see it that way. To him: this is a story of a community. Bernard would never use the “A film by…” tagline many directors use, for example. “How can you say it’s a film by…you cunt,” he exclaims. “With Frank's script? Fuck off! The shame…”

Indeed, so much of the success, in Bernard’s eyes, is owed to Frank and his script. He puts it “on a par with some of the greatest writers” and likens it to Oscar Wilde: “a working class Wilde of the 80s”. Some of the lines, like Teresa’s expressed dream of “drinking vodka, getting fucked and stuffing chickens”, still jump from his mind. It was that manner of talking, especially from female characters, that he sees as the innovation. “Working class, earthy women who had hard lives, who were mothers, who were daughters,” he says. “Who were constantly portrayed as sluts or low lives, or treated with derision and contempt because they were poor and it was somehow their fault. But it wasn’t — and people were screaming for that.”

Not everyone got the message he was looking to send, mind. Amid the feverish success, Margi and Alexandra Pigg — who played Elaine — were invited onto Terry Wogan’s show. “That fucking prick,” Bernard says. “His sexist response was to effectively tell both of those girls they were sluts. He was a bastard — I was so upset”.

For me, the film isn't just exceptional at capturing Liverpool, but in capturing a very specific moment in a person's life. It's that feeling you have as a teenager, mooching about in parks as the sun goes down, staying out, going from one friend's house to another's, even though there's nothing to do. Nothing ever happens, but despite all evidence to the contrary, you’re convinced that if you’ll go home, you’ll miss it — that moment that’s going to change your entire life. Presumably it’s the same sensation that prompts Elaine to spend her savings on two hotel rooms for her, Teresa and their two sailors, imploring Teresa to stay out longer ("Well, here’s my chance for something else. And yours as well. Even if it is just for the one night, we’ll always have the memory of it, won’t we?"). She feels poised on the brink of transformation.

It’s hard to know whether another Letter to Brezhnev could be made today, how easy it would be to replicate its magic. Bernard is hopeful, he says there’s always another generation of talent on the up, but admits that the conditions from which his group arose were unique. Around Liverpool in the mid-70s were streets and streets of disused buildings and warehouses, all waiting for hippie-ish kids to bundle in, come together, make something. Certainly, much of it was rubbish, but occasionally the stars aligned. Maybe a little of that spirit has been lost.

It was certainly a film that rose out of a singular moment. Perhaps it could’ve only have been made by a clan without a collective pot to piss in. Their resourcefulness spoke to a particular time and place; high unemployment and the industrial decline Liverpool was suffering in the 80s. But Bernard doesn’t buy into the idea that the working-class backgrounds of much of the crew meant they could automatically produce a better film about the working class. “Then it has to work the other way and that means I can’t make a fucking Shakespeare and Frank can’t make an adaptation of Emily Bronte,” he says.

At the end of the film, with Peter having returned to Russia, Elaine can’t let go of the overwhelming power of the night she spent with him. She writes a letter to none other than Leonid Brezhnev, leader of the Soviet Union. A ticket to Russia arrives in exchange. It’s a simple film in many ways, a kind of Hollywood spirit infused with the language (and chicken factories) of Kirkby. Ebert said it was about how “idealism can be a way of escaping from the rat race”. To much of its crew, the same applied.

Comments

Latest

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

And the winner is...

Losing local radio — and my mum

A place in the sun: How do a bankrupt charity boss and his councillor partner afford a “luxury” flat abroad?

Two Russian sailors walk into a bar — the rest is cinema history

‘Letter to Brezhnev’ is Liverpool’s greatest rom-com