Tinker Tailor Teacher Spy: The Liverpool academics at the centre of a free speech row

What to do when there’s a mole in the ranks?

*names have been changed

It was the evening before the first meeting that Michelle* realised there might be a problem. The phone sounded: a friend had seen a post on social media. An “infiltrating insider” had been spying on their group, waiting to leak the time and location of the meeting.

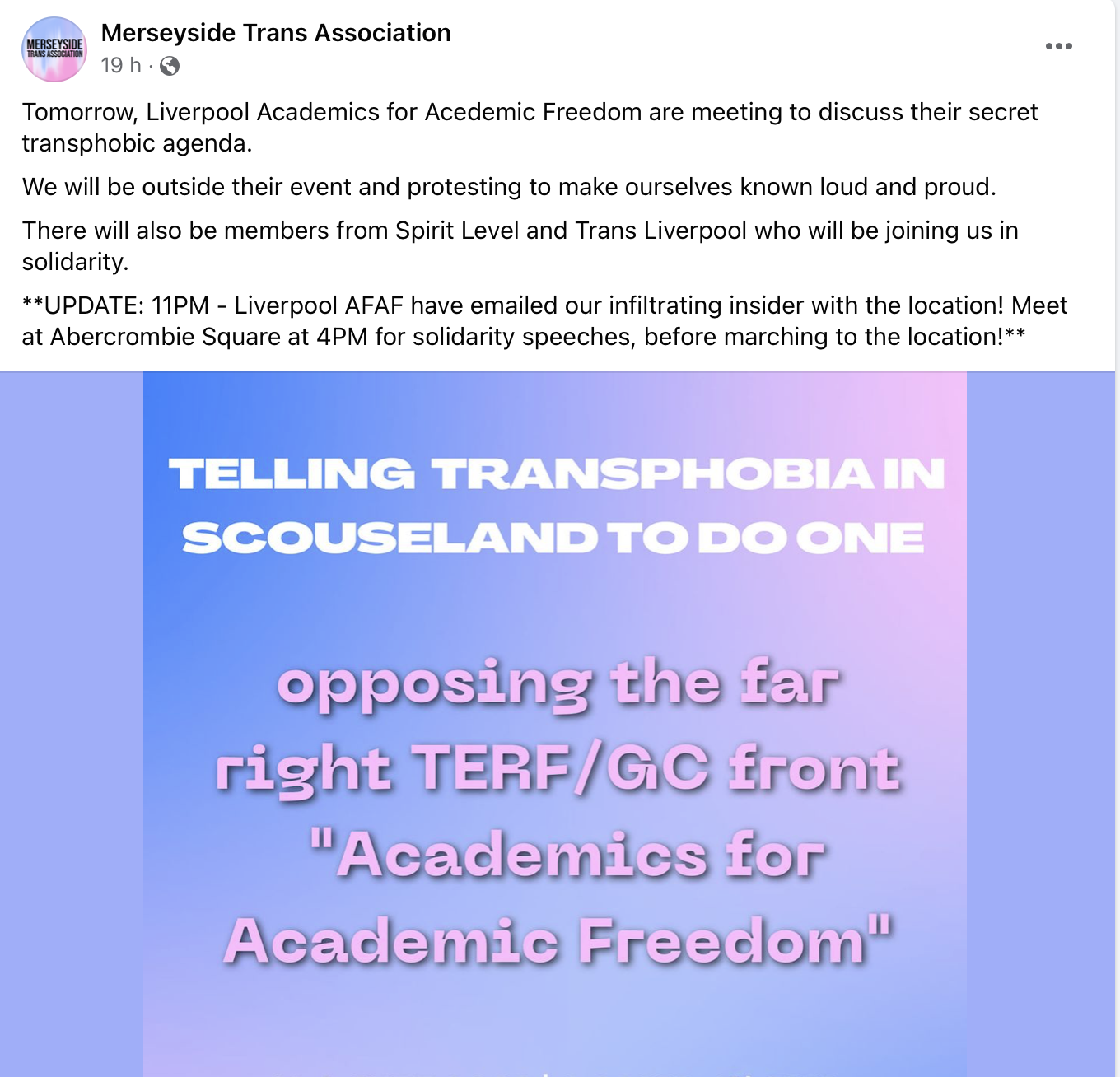

‘Tomorrow (June 14th), Liverpool Academics for Academic Freedom will be meeting to discuss their secret transphobic agenda,’ the Facebook post read. ‘We will be outside their event protesting to make ourselves known loud and proud.’ Attached was a poster with the words ‘TELLING TRANSPHOBIA IN SCOUSELAND TO DO ONE’ printed on it, with instructions to ‘mask up for your own protection’.

But Michelle, a law academic at the University of Liverpool, was puzzled. Her planned meeting for the city’s branch of Academics for Academic Freedom (AFAF) wasn’t about trans people, or trans rights. Posters were being made and circulated, encouraging activists to attend the meeting in masks, megaphones in hand. But Michelle tells me she doesn’t have an anti-trans agenda. Which begs the question: how did she reach this point?

Growing up in Turkey, Michelle saw her parents imprisoned during the military coup of 1980. The same coup that later saw 50 people executed and thousands die in prison. Her parents — members of the resistance at the time — taught her to fight for her beliefs, just like they had. “This really dominated my entire life,” she tells me, explaining that she relocated to the UK in pursuit of the freedoms she could not have in Turkey.

Moved by the terror she saw as a child, this year Michelle founded the city’s branch of AFAF: a group that, at its most basic level, believes that freedom of speech is essential to making progress in all academic fields.

The first meeting was intended to be somewhat of a coffee morning, Michelle tells me — it was meant to be a way for the group’s members to get acquainted with each other and discuss their thoughts on academic freedom and free speech. She is well aware that free speech is a hot topic, she says.

Michelle explains that everyone on AFAF’s mailing list was sent information about the time and place of the event. It was the first meeting to be held in Liverpool, with around 15 academics, students and university professors RSVP-ing to the initial invitation. After her friend alerted her to the social media post, Michelle was baffled. “The meeting was predominantly about how we can create a more conducive environment in universities,” she says.

She explains that when she first got wind of the protest, she contacted the university’s security team out of fear of a huge turnout. “It was a bit precarious,” she says, “it’s a really delicate balance because on the one hand, you want to make sure there’s security, but you don’t want to emphasise it too much or it’ll be cancelled.” The social media post was later deleted, but she tells me that two or three people did show up for the protest, with one person manning a megaphone. “I wasn’t worried about my safety or anything,” she says. “But you know, for some [members] it was too much for them,” she adds, stating that one member of AFAF kept clear because of the backlash they’d seen online.

One of the academics who did attend that first meeting was Paul Garner. Post readers may remember him, but for those of you that missed out — let me jog your memory. Paul is an epidemiologist and an academic at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. After contracting Covid-19 in early 2020, he developed long Covid, suffering from chronic fatigue and struggling to make a full recovery. His research turned to finding a cause and a cure for the illness, and in 2021 he published a blog post stating he’d found some of his own symptoms were, in part, psychosomatic. His blog post was divisive to say the least, with Paul receiving death threats, pictures of guns and terrifying messages inciting violence from a fringe activist element within the ME community. ‘You have blood on your hands. And we are not scared to take measures since we got NOTHING to lose… We know where you live, where you work and about your loved ones,’ read one email he received.

Paul’s experience of online abuse doesn’t stop there. Just two weeks ago, a paper he was working on — challenging microclots as a cause of post Covid-19 syndrome — came under fire, with one Twitter user stating it was the “banality of evil”. The banality of evil is a phrase coined by political thinker Hannah Arendt, used to describe the Nazis’ execution of the Jewish population during the Holocaust. He tells me this is why he’s joined AFAF, adding that these kinds of social media attacks are “bad discourse” in the academic field.

Paul tells me that during the AFAF meeting, they talked about feeling safe as an academic online, and he shared his own experience with online abuse. “It was lovely to be among all these kinds of kind, gentle people that came from all sorts of walks of life, disciplines — from law to social science, all of them all different shapes and sizes with their own story to tell,” he says. He adds that part of an academic's job is “to be out there, stimulating debate”, and they should have “unrestricted liberty” to question established ideas and theories — something that was also discussed in the meeting.

Michelle agrees, arguing discourse is key. “If people think you’re fundamentally wrong, you should engage in debates and discuss these things.” She adds that in recent years, academics are instead being “vilified” for publishing work that goes against the grain. What this all boils down to is freedom of speech, she says, and when people think it goes too far. Who decides when it does?

Naturally, I’m eager to speak to one of the protesters against AFAF in June in case there’s something I’m missing. While what Michelle says seems perfectly reasonable, it’s become a truism online that plenty of hateful things have been said under the guise of free speech. I reach out to the Merseyside Trans Association — the group that organised the protest — but don’t hear back. I send emails to the other groups involved in the protest in search of an answer. Silence.

Then on Wednesday night, I’m close to filing this story when I get a phone call from an unknown number. “Hello?” I hear a quiet voice down the line. It’s the person Michelle alleged leaked details of the meeting online — they’ve asked to remain anonymous for this story out of fear of backlash, but denied they had anything to do with the protest, or the leaking of information. They tell me that a close friend asked them to sign up to AFAF’s mailing list, requesting they update them with details of the meeting when released. I ask them if their friend is the one who organised the protest. They skirt the question, but insist that in the end, neither of them attended the protest — or the meeting. They add that while they were not involved, they know AFAF have “retweeted some anti-trans things” on Twitter, so the picket was understandable.

On checking these claims, the lion’s share of the Liverpool AFAF Twitter account currently seems to be dedicated to retweets on exactly that topic, and only from one perspective: gender critical. In the space of the last five days alone, there’s a retweet about a gender critical website being blocked by the Great Western WiFi network for being linked to “terrorism and hate”; a retweet about the NHS Trust’s new gender diversity policy, arguing a cis woman complaining about a trans woman sharing a toilet with her could stand to lose her job; a Telegraph article about a woman whose operation at a London hospital was scrapped after she requested only cis women be involved in her care — to name just a few.

I call up Michelle again to ask about these Twitter posts and she tells me that while AFAF is not a group dedicated to discussing issues around gender and sex, “at the moment there’s a lot going on” about it in the media. She ascribes the uptick in tweets on that subject to her reaction to the protest. She is quick to point out to me that at the time of the meeting in June, the tweets on the account were not just about gender, and as I scroll back I find a plethora of tweets about other topics; an article about Elon Musk publishing government censorship requests on Twitter; a piece about an epidemiologist who was critical of lockdown measures, and so on.

I ask her if she thinks the tweets that dominate the account nowadays are transphobic. “I do not agree with that,” she says. “It’s never about trans people and their rights, it’s about free speech.” She reminds me that the group consists of many members from all academic backgrounds, naming Paul as a key member who has faced backlash again in recent weeks for an issue unrelated to gender. “In a university setting, many groups co-exist together and one person's rights cannot outweigh another person,” she says. “In this area there has to be freedom of speech, and freedom of speech always includes freedom to offend.”

Yet it’s easy to understand why activists in the city reacted so strongly to the formation of AFAF in Liverpool. While being able to discuss difficult topics openly is essential, being trans or even advocating for trans rights can put people at risk. Last autumn, Sefton councillor Laura Lunn-Bates told the Echo she received online abuse after voicing her support of transgender people, eventually forcing her to remove her personal details from the council website over concerns surrounding her safety. Transphobic hate crimes in Liverpool have been on the rise (as indeed, they are nationally), with the Echo stating in the same article that more incidents were reported to police in the first eight months of last year than over the course of any full year since 2019. Last autumn, a report published by the Home Office speculated that the jump in transgender hate crimes from 2021-2022 could be connected to something as ephemeral as discussions on social media: “Transgender issues have been heavily discussed on social media over the last year, which may have led to an increase in related hate crimes.”

It strikes me that free speech is only truly possible if there’s a level playing field between both camps. It’s hard to know how to create that equality for a group of people who are often subject to far more violence and disruption in their lives than the majority (transgender people in England are twice as likely as their cisgender equivalents to be the victims of crime).

Andi Herring is the co-founder of the Liverpool City Region Pride Foundation; I call him up to ask him about the social media debates over free speech and gender identity. “One of the big things for me is that we have all these debates or clashes of opinions on Facebook, but no one is actually talking to the young people in the community,” he explains. “They’re really clued up, they know themselves and we’re taking that away from them when we’re having these debates behind closed doors.” He notes that while open discussions can be a useful tool for queer people to discover their identity, these talks need to be approached sensitively and with empathy in mind. “I think there’s a lot of credit to be given to listening and empathising with each other, isn’t there?” he says.

I put this same sentiment to Michelle, and she is quick to note that she understands the complexities around gender identity, and by no means wants to cause any distress. She tells me that a person in her own life is transgender, and her personal interest in the topic stems from trying to better understand them, and her own experiences growing up. “I came from Turkey and used to go to Pride and protests, and you know, you’re putting your life in danger to support marginalised people,” she says. “I fully support it, and for people suffering from gender dysphoria, they’re not happy, they’re in tremendous distress.”

The question of freedom of speech in an academic context has attracted so much press coverage over the past few years you can feel like you’re drowning in it at times. Few scenes capture the current state of Britain as succinctly as an irate student activist and an irate presenter shouting at each other on a breakfast TV programme. Words and phrases like “woke”, “gammon” and “cancel culture” bounce around the walls of a brightly-lit studio and straight into our living rooms. Every single day.

Beneath that noise, it’s easy to lose sight of what “academic freedom” even means in the first place. I’m reminded of a letter from Professor Grace Lavery in response to a Guardian editorial. The editorial argued that the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) bill doesn’t prove that the Tories cherish free speech — and that it actually shows the government is moving the culture war onto campus grounds. Lavery, who is a trans woman and an academic, is a passionate supporter of freedom of speech — but she’s also allergic to the fogginess that seems to permeate most conversations on the topic. In her letter, she points out that the editorial mixed together three distinct categories.

One, academic freedom: “the collective right of scholars to conduct research without external interference”; two, free speech: “an individual right of everyone to say more or less whatever they wish to” and three, what she refers to as a diversity of opinion: “which may or may not be “a good result”, as the leader puts it, but is usually an attempt to crowbar discredited theories and methods back into prominence.” She argues that the third category generally contradicts the first.

She also argues that academic freedom and free speech can sometimes even be in opposition — like a journal having the academic freedom to reject publishing an article submitted to it; a professor having the academic freedom to fail a weak student or to choose to leave a book off a course.

In the non-fiction work, Knowledge, Power and Academic Freedom, Joan Wallach Scott criticises "the increasing tendency to treat academic freedom as synonymous with free speech and with the unfettered right of a student to his opinions in the classroom." Scott is a professor at Princeton, but this tendency to blur these two topics seems to hold true for Britain, too.

Academic freedom was established as a legal right in the UK by the 1988 Education Reform Act, and allows staff to “question and test received wisdom and to put forward new ideas and controversial or unpopular opinions without placing themselves in jeopardy of losing their jobs or the privileges they may have.” While Paul may have received tasteless criticism for publishing his work and Michelle may advocate for free speech, I’m not sure how much this has to do with academic freedom, as per the legal definition — the risk of them losing their jobs or privileges. Perhaps the fear is that the backlash against their meeting could build to a stage at which this threat became real.

Michelle is keen to point out that she’d have been “quite happy” to talk to the person who shared details of the meeting; the so-called mole. “If they actually came to the meeting, we could talk. If you’re in education or a workplace it should be legally, and also philosophically, open to all kinds of diverse groups,” she says.

So, here we are. Nearly two months on from the protest over AFAF’s initial meeting, Michelle is yet to organise a second members meet-up. I ask her if the whole situation has deterred her. “No,” she says. “It just makes me more passionate because it’s so misunderstood — I’m not going to be silenced in any way.” She explains that the planning will begin when the new academic year commences in September.

Will she ever get involved in a debate over sex and gender? “There are people who have asked me, you know, do you want to get more involved? But actually, I am trying to keep it more limited.” Why? I ask. “It is an extremely inflammatory area,” she says. “It’s very difficult to publish books, to publish papers, and you kind of limit yourself with that area of research.” For now, Michelle tells me she will stick to what she knows: law and economics.

Comments

Latest

A ‘stitch up’? How Wirral council bungled Big Heritage

Merseyside’s buses are coming back into public hands. Why not trains too?

From Jimmy McGovern to Len McCluskey: The household names rallying behind Writing On The Wall’s employees

The lost department stores of Liverpool

Tinker Tailor Teacher Spy: The Liverpool academics at the centre of a free speech row

What to do when there’s a mole in the ranks?