'The whole place is so full of mysterious questions'

A lot of what's been written about 'Williamson's Tunnels' isn't true. So what is?

It was a long-abandoned stable yard — overgrown and derelict. People passing it on their way through Edge Hill probably wouldn’t have known it existed, hidden as it was behind high walls and fences.

Decades before, early in the 20th century, the Lord Mayor of Liverpool had stabled his carriage horses here — sleek, strong animals that took part in great municipal festivals. It even had a stud, where the nags were reared. Before that, it was a scavenger’s yard — with horse-drawn carts bringing in re-usable waste from across the city.

And long before that, around 200 years ago, when Edge Hill was a hamlet far from the madding crowds, it was a work yard used by the secretive local tycoon Joseph Williamson. The stone he quarried from the ground was cut and shaped here, before being used to build grand Georgian houses.

It was only in the 1990s when a small group of local people started to take an interest in the yard. They had heard about secret tunnels under Edge Hill — about great chambers and mysterious slot mines reaching far into the Permo-Triassic sandstone below. A double-arched opening — said to be an opening to a tunnel — had long been visible on the site.

A few like-minded people got together to make sure nothing happened to the tunnels. Surreptitiously, they made their way in, scaling the fences and exploring by torchlight. The visits confirmed the rumours: there were entrances to underground passages, some more accessible than others.

The council had decided to sell the land to developers, who would bulldoze the yard and cover over the tunnels. The interested locals formed a pressure group to prevent the sale and protect the underground entrances. They wanted a crack at reopening the tunnels, which had lived in the folklore of Liverpool for two centuries.

It was a quixotic mission — one that combined the child-like wonder of exploring tunnels with a deep curiosity about Williamson himself. They wanted to understand what he was doing in the depths under Edge Hill; what he was thinking when he sent men to work underground.

They still want to know those things.

A nightmare maze

Born in 1769, possibly in Warrington, Williamson worked at a tobacco and snuff factory in Liverpool, owned by the wealthy Tate family. In 1802, having worked his way up through the ranks of the company, he married his employer's sister, Elizabeth Tate. The following year, ownership of the factory passed to Williamson.

The couple’s home would be 44 Mason Street in Edge Hill. Williamson also owned a number of other properties nearby. But the houses were unusual. Some of them backed onto an almost sheer drop, with huge arches behind each of them to provide the residents with enough space for rear gardens.

In 1818, when Williamson was in his late 40s, he sold the tobacco business. What happened next is the subject of deep dispute and great conjecture. What we know for sure is that Williamson employed a large number of local men to work for him, mostly underground.

It was a time of great poverty and mass unemployment in England, many men having recently returned from the Napoleonic War to find their old jobs gone. It's been estimated that Williamson employed over half the able-bodied labouring population of Edge Hill at this time.

Skip forward to 1845, five years after Williamson’s death, and a Liverpool antiquarian called James Stonehouse wrote an extraordinary account of what the tycoon later known as the “King of Edge Hill” had been building: a mysterious but "stupendously useless" subterranean world.

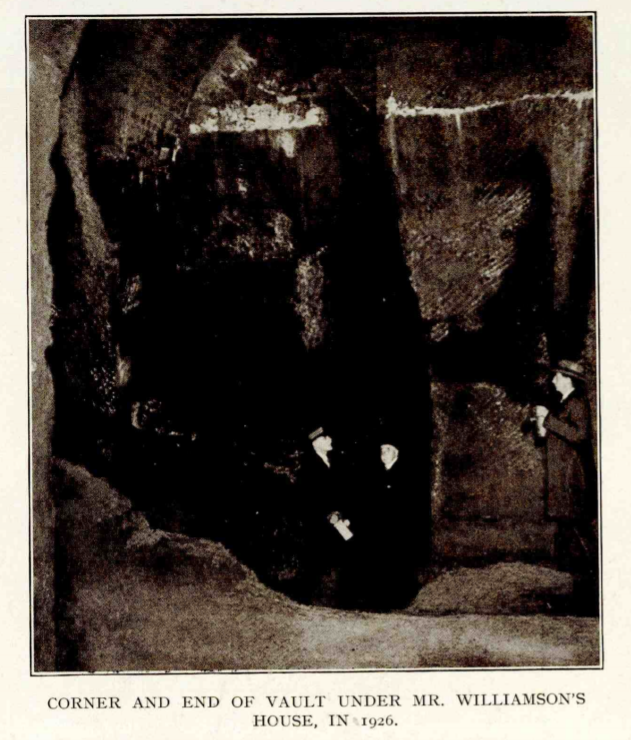

Stonehouse said he had visited the tunnels, and wrote of "vaulted passages” and “pits deep, and yawning chasms". The houses built by Williamson were “vaulted to an immense depth” Stonehouse wrote, and some had five or six tiers of cellars. He describes cathedral-like halls and even two triple-story houses — complete with sandstone spiral staircases — carved out of the solid rock beneath Smithdown Lane.

He sees rats “of immense size”, including a snow-white rat that he tried to catch but which escaped into a long passage. He also suggests the tunnels were haunted, quoting a local man living on Mason Street, who says one night his family were awoken by “yells and sounds of agony” emanating from the vaults under their house.

Decades later, a local historian called Charles Hand wrote in a similar vein about his own visits to the tunnels.

Tied together, in a single file, and carrying as many lighted candles as we could get, while the last one of the party always held a ball of string which he unwound as we proceeded on our way, the other end of the string having been securely fastened to a large stone which lay by the entrance, we traversed these strange and wonderful passages, literally in “fear and trembling,” afraid yet fascinated by the eeriness of it all, dreading we know not what, yet going on.

Hand’s descriptions of what he found on his Saturday afternoon expeditions as a boy were lurid, at times gothic. He conjured in the imagination of his readers the tropes of Victorian ghost fiction: scary passages under large houses and “crypts” in the “bowels of the earth.” At one point he writes:

They [the underground works] are beyond description; words fail to give an adequate idea of their appearance. Dungeons carved out of the solid rock, with no light and no ventilation, the only access being through a heavy wooden door; vaults with a roof of four arches meeting in the centre in a manner that present-day builders would not think of attempting; monstrous wine-bins and many stone partitions for enormous quantities of bottles; massive erections of masonry and stone benches — all apparently without the slightest object or motive.

How big were these underground works, and where did they lead? Hand dangled the possibility that they were labyrinthine and endless — “a nightmare maze of constructed tunnels and caves,” he says. “Nobody knows their extent.” He says one adventurous youth offered to crawl on hands and knees down one of the tunnels. “He stumbled and splashed for a great distance until we could hardly see the candle,” Hand writes, at which point the rubbish that had accumulated in the tunnel prevented his passage.

It was believed, the historian says, that this particular tunnel “originally extended as far as St. Mary’s Church.” At one point, Hand describes walking for a mile without finding an ending.

What was the point of the tunnels? Some have suggested they were built as caves to store smuggled contraband from the port or served as a refuge for a religious cult who believed the end of the world was nigh.

Over the years another suggestion has grown in popularity: that Williamson was a philanthropist who wanted to employ as many men as possible during a period when the Napoleonic wars had driven up rates of unemployment and poverty. Men were given obsolete tasks, some said, ferrying earth from one place to another and back again.

The volunteer

Tom Stapledon has spent the best part of 12 years in the tunnels. He’s a tour guide, a volunteer “digger” and a trustee of the Friends of Williamson’s Tunnels too. He’s 74 now, but he got involved 12 years ago.

He had retired early at the age of 59, and “didn't go looking for a hobby,” he remembers. But then a hobby found him. His passion is vintage cars, and one day he was walking around a car rally field, when someone approached him, looking excitable. “I walked past this tent and a little man grabbed me,” he says. Inside the tent, the man showed off photos of the tunnels, singing their praises.

Stapledon walked away with a leaflet in his hand and soon made a visit to the tunnels for a tour. “The first time I went down there I was hooked,” he says. “I wanted to be part of the team.”

On the phone, he is a precise man, detailed in his descriptions. Some people would call him grumpy. If you were being more charitable you might say he’s just tired of reading media reports about the tunnels that don’t tally with his extensive research. “The idea of Williamson burrowing to the church and under the streets and to the pub,” is rubbish he says. “They are not a labyrinth of tunnels.”

On Hand’s description of walking for a mile without finding the end of a passage, he says: “We’ve been debunking this ever since.” The accounts written by Stonehouse and Hand are a string of lies and exaggerations that have obscured the truth for decades, Stapledon insists. Unfortunately, though, they are two of the only sources we have.

When The Post contacted him to fact-check the first draft of this story, he seethed at the inclusion of some of those old myths and oft-repeated inaccuracies.

So what is the truth? Stapledon says there is no evidence to support the popular view of Williamson as the “Mad Mole” — a burrower who preferred being under the earth and built long, labyrinthine tunnels for his own use, including great banquets in his subterranean chambers. The explanation for his underground works is much more prosaic and commercial, Stapledon insists.

“He was digging deep slot quarries,” he says. “Digging the stone out of the ground, and hauling it up and out.” The stone was used in the many buildings Williamson erected in the area, and he probably sold more to builders across the city.

Stapledon assumes that after bringing up all the stone he needed, Williamson continued to quarry it out in order to keep the men occupied. “He would give stone to anyone who asked,” he says. In this interpretation, the reason for building brick arches and tunnel walls wasn’t to create chambers for the tycoon’s use — it was just to enable him to build houses on top by re-establishing the ground level.

Researchers at Edge Hill University agree. They note in a detailed study that the work was carried out using well-established quarrying techniques that produced large chunks of sandstone suitable for building houses, much in demand in Liverpool’s Georgian era. “They were dimension stone quarries that were restored to good land by a novel technique,” the authors say adding: “In effect his business acumen produced one of the earliest and most profitable forms of quarry restoration.”

In this telling, the local tycoon was operating a series of unregulated slot quarries away from the prying eyes of the authorities and the taxman, and the tunnels were merely an attempt to keep the ground secure. Is this why Williamson was so secretive about his works, and why a friend of his threatened to sue the Stonehouse when he threatened to write about his visit to the complex?

The rediscovery

"I've always been fascinated by tunnels, even as a kid,” says Chris Iles. “If I saw a cave or a tunnel, I’d be off exploring.” By day, he is a train driver — a job that takes him into plenty of tunnels. In his spare time, he explores the ones Williamson left under Edge Hill. “As much as we're all working to preserve this hugely important [piece of] Liverpool heritage, in a more selfish way we are also doing it because we love it,” he says.

In 1999, he joined the Friends of Williamson’s Tunnels, shortly after the re-discovery of the Paddington complex — a triple-level stretch of impressively vaulted excavations.

The notion of discovering secret tunnels might sound exciting and glamorous. But the bulk of the work, especially in the early days, amounted to waste clearance. At some point in the nineteenth century, after Williamson’s death, the tunnels had found a new, more practical purpose as enormous rubbish bins. Householders and business owners living above them broke through to the hollows and started dumping their refuse in the depths below.

"We explored as much as we could in Paddington’s chambers which were at this time completely filled in,” says Iles. Tonnes of Victorian rubbish had to be brought to the surface and taken away. “We discovered lots of interesting artefacts among the debris including ink wells, a gold sovereign, clay pipes, and lots of pottery,” he says.

The Friends received permission from Liverpool City Council to actually clear the tunnels in 2012. Digging by hand two days a week, volunteers cleared one hundred and fifty-nine skips full of debris in four years, finally revealing what Iles describes as the "cathedral-like chamber that we have today". That’s a huge cavernous room, 60 ft below ground, with a ceiling that’s 40 ft high.

There is also what the group calls the "Banqueting Hall”, which is on the site of Williamson’s house. “It’s a wonderful chamber,” says Stapledon, with arched brick roofs about 20 ft high and 60 ft long. There’s no evidence of the lavish banquets that local folklore says Williamson held in the hall, but the name has stuck.

Iles and his colleagues are not the only people tunnelling in the depths. There is a separate group of volunteers, the Williamson Tunnels Heritage Centre, who focus on the Old Stable Yard site on Smithdown Lane.

To the volunteers, the groups are totally different, focusing on separate stretches of the tunnels. To the outside world, they are confusingly similar, and punters often get them mixed up. “That’s Liverpool for you I guess,” jokes Iles. “Not content in having two Premier League football teams, and two beautiful cathedrals, we also have two Williamson’s Tunnels tours too.”

The Great Tunnel

In 2019, the volunteers discovered a narrow rock-cut tunnel in the sidewall of the Banqueting Hall. “This small tunnel takes you into yet another large chamber, potentially of a similar scale,” says Iles. It had been buried for 180 years and has been christened the Magnet Chamber by the volunteers.

“That was a really exciting dig,” says Stapledon. “We had access to the Banqueting Hall for 25 years, and we never knew about another chamber right next door.” It’s a tantalising new chapter for the team, but they hope it’s just a stepping stone to something even bigger — something that has been a Holy Grail for the volunteers for many years: The Great Tunnel.

“We hope that in time this will lead us into the long-lost Great Tunnel which has so far evaded us,” says Iles. What is the Great Tunnel? Nobody really knows. It’s believed to be one of the biggest underground structures in Williamson’s network. Military records show it was used as a drill hall more than 100 years ago.

“The real significance of the great tunnel is that it’s so elusive,” says Stapledon. “We tried in 2003, digging in from a magnet joinery factory. In 2017, when the factory had been demolished, we pleaded with the council to let us go from above, and we didn’t find it. So it’s still eluding us.”

He hopes that if they can clear the Magnet Chamber after the pandemic is over, they will find an access to the Great Tunnel. “We hope it still exists and it hasn’t collapsed,” says Stapledon matter-of-factly. If it has collapsed, it would be a disappointment laden with irony for the men who have dedicated their lives to reclaiming Williamson’s subterranean works.

Where does it lead? They don’t know. “We now know that Williamson did some incredibly strange things, which are very difficult to explain,” says Stapledon. That’s what motivates the men. They have spent more than a decade thinking and reading about the King of Edge Hill, and every dig is another chance to get closer to the man himself.

“The whole place is so full of mysterious questions — an awful lot of questions that nobody will ever be able to answer,” Stapledon told The Post. “When you look at some of the structures underground, you think: How the hell did he create these? What the hell was he doing building all this stuff?”

For the volunteers, the pandemic has been a period of frustration. The biggest privation is having to spend so much of their free time above ground. "The hardest thing has been not being able to go to the tunnels and work every week,” Iles says. “Every one of us volunteering regularly thoroughly enjoys doing what we do.”

At peak periods of digging, the Friends have had 15 to 20 volunteers on site. They were down to about 10 regulars before the pandemic. “I was getting a bit despondent last year, because some of our regulars were moving away,” says Stapledon, “It was really quite sad.”

That can happen when a big project comes to an end. He says when they post a new breakthrough on their Facebook page, “people come out of the woodwork” again. A breakthrough like finding the Great Tunnel will swell the team to a record size. “We know they will be back when we need them,” he says.

The Post is still early in its life. We hope you are enjoying our occasional stories. We hope to start publishing more regularly later this year — when we have the resources to build a little team and we find the right journalists to work on the project.

Talented journalists in the region who would like to write for us should email editor@livpost.co.uk with their ideas. And if you have a story you think we should be covering, please get in touch by replying to this newsletter or using the email above.

If you like our stories, please do forward this newsletter to a friend or use the share button below to share a link via Whatsapp, text or on social media.

Comments

Latest

From Jimmy McGovern to Len McCluskey: The household names rallying behind Writing On The Wall’s employees

The lost department stores of Liverpool

Last minute drama, local revamps and Liverpool Doc Club

From Simone's to Belzan: How a hospitality magnate seduced Liverpool's tastemakers

'The whole place is so full of mysterious questions'

A lot of what's been written about 'Williamson's Tunnels' isn't true. So what is?