The unbeatable, unforgettable Liverpool Woman

‘The real Lilys didn't really 'do' age; instead they did rage, wit, and defiance’

She's shopping in Aldi with her hair in rollers, sashaying down the aisle leaving a waft of eau de Fake Bake in her wake. Look at her – falling over the pavement outside the bar while her friend attempts to have a wee in the gutter and light a fag at the same time.

Lip flips and big hair; spoolie brows and Polygel nails; permatans and major, major attitude, whatever the occasion, circumstance or audience.

Many people might argue that the ‘Liverpool girl’ is the stuff of lazy legend, fuelling a stereotype that vilifies or lionises Liverpool itself according to the narrative being promoted. Plenty of girls across the UK do the supermarket rollers/fake tan/trout pout thing just as well (or badly). However, Liverpool girls – gearing up for the metamorphosis into the arch matriarch that is the legendary Liverpool Woman – did it first... and do it better. And now more than ever, I'm grateful to have Liverpool Woman firmly ingrained in my DNA.

Of all the ages and stages I've been through, turning 60 is the one that's given me the most to think about. Milestones (and six decades on Earth is surely quite the milestone) bring on reflections that go beyond considering getting my eyebrows tattooed. For me, those reflections have been along the lines of “So, who am I, really, and how did I get here?”

There's been no looking back in anger; to the contrary, I've been looking back in gratitude, counting blessings, raising (several!) glasses to loved ones lost, absent friends and right-here-right-now key players in the story of my life. It's strange to think that, only a handful of years ago, I'd be an official pensioner now. And yet here I am, still hoping to get my big break as an author, celebrating having just bought the flat that I've rented for the past 25-plus years – and still wondering what it feels like to be a grown-up woman.

I clearly remember what 'being a grown-up woman' looked like to me, so many years ago. I remember being fascinated by the hard-faced, head-scarfed women shopping in St John's Market, berating the butcher for suggesting that the free bones they wanted thrown in with their pork chops were to make soup for the kids, not the “treat” for the dog that they claimed.

Later on, the same women would be knocking back Aussie Whites in Yates's Wine Lodge on Great Charlotte Street, either sitting in grim, watchful silence or sharing tawdry gossip, knowing looks and raucous laughter, putting concerns about their husbands and their needy-but-much-loved kids (“Ah yeah, but our Chardonnay's a little angel, really”) on temporary hold while they united in their refusal to give up and give in to the hardships that dictated their all-too-real lives.

You wouldn't want to have crossed one of those women – but by God, you'd want them on your side in a fight. As Paul O'Grady (Lily Savage) once said, “Yates's was full of Lilys: hard, hard women with sharp nails, sharp tongues, and blunt, brutal lives that forced them to age before their time.” But the real Lilys didn't really 'do' age; they did rage, and wit, and defiance instead.

O'Grady's Lily Savage was the epitome of the “exasperating, irritating, vacillating, calculating, agitating, maddening, infuriating hag” that so riled George Bernard Shaw's Professor Higgins in My Fair Lady. Lily represented the Grand Dame of the Liverpool Woman, far removed from the neat, sweet, simpering handmaidens that magazines like Woman’s Own, back in the 1980s at least, told all women they should be. While I never dreamt I could be like Lily, I sure as hell wanted her bravado, her sagacity... and her wigs. Was Lily the ultimate role model who eventually inspired me to 'grow up'? In part, yes – and much of her does indeed live on in me today. I have to admit, though, that I was only ever a tourist in the real Land of The Lilys.

My mum was born in Liverpool in the late 1930s, and grew up in a neat suburban avenue roughly between Childwall and Roby – a long tram ride away from Liverpool city centre, and worlds away from Yates's Wine Lodge. Given her comfortable upbringing, my post-war teenager mum could easily have got ‘a good job’ on the perfume counter in Boots or in the glove department in George Henry Lees before marrying a respectable businessman and settling down in a nice house in Gateacre.

But by the time the 1960s swung into view, mum had met and married my dad: a distinctly non-suburban man who, despite also being born in Liverpool a decade earlier than mum, spent his late teenage years at the Beaux Arts in Paris and, like TS Eliot's J. Alfred Prufrock, measured out his own life in coffee spoons while maintaining a cavalier disregard for the 'bourgeois' concept of nice houses and 2.4 kids.

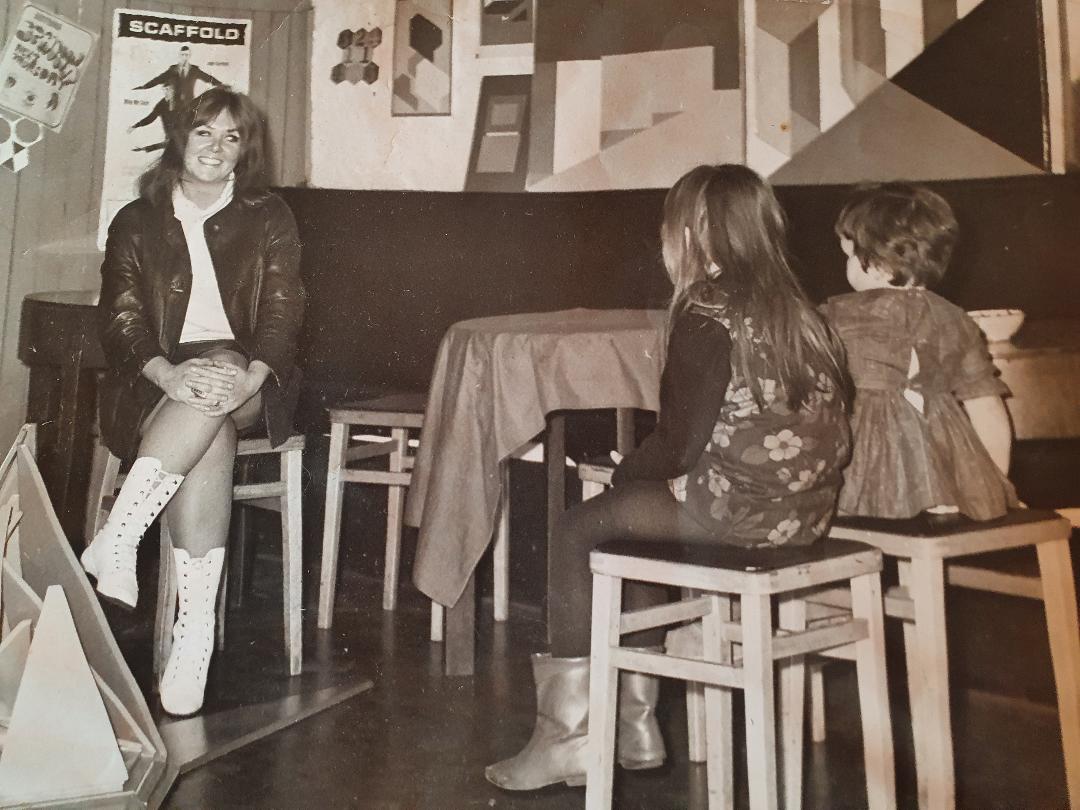

Mum designed children's clothes for a while, sketching her Patsy Poppets range in the kitchen of our flat on Gambier Terrace while dad designed his life in his own unique way. In 1966, when I was two years old and my sister Vicki was six, they opened the Everyman Bistro and our family relocated to a huge, rambling ground-floor flat on Aigburth Drive.

I spent many late afternoons sitting next to mum at the dressing table in her bedroom, watching her getting ready to go to work. She’d choose a pink crepe de chine Biba top, perhaps, or a green silk Liberty print blouse, always with blue jeans. She'd tie a paisley scarf around her head in a chic, complicated turban and spray herself with Estee Lauder's Youth Dew before reaching for her glazed pink lipstick; “give me a kiss before I put my lippy on,” she'd say – and I would.

My mum didn't do school runs and lunch boxes, or strict bedtimes, or Sunday roasts. But mum was telling me, in her own, quietly loud'n'proud way: one day, you too will be a woman in your own right. My mum was fabulous. Role-model #1? Tick! But when I reached the age of 12, mum was usurped.

Behold Avril – a family friend some 25 years older than me – sitting at our kitchen table in our big house off Ullet Road (we'd vacated Aigburth Drive by then, via a semi-commune in Wales) smoking a cigarette and drinking black coffee, her Ziggy Stardust hairdo all mussed up and traces of last night’s make-up still evident around her huge green eyes.

Avril was born in a tiny house in Kensington, and her mother probably frequented Yates's on a regular basis... but not Avril. Avril took a job as a waitress in the Everyman Bistro where she met a Dan-Air pilot (Dan-Air, back then, being the equivalent of EasyJet, today) with whom she had two sons of similar ages to me and my sister, and who she looked after with a level of just-about-fondness for their wellbeing that one would expect a friendly neighbour to maintain while temporarily looking after your cat. Avril looked like the sort of person I’d seen in the backdrop of photos of Berlin-era Iggy Pop, or linking arms with Debbie Harry after a night out in Studio 54. But Avril wasn’t a photo; she was real. And in our house. And smoking. And I wanted to BE her.

So it came to pass that, for my fifteenth birthday, I requested dinner at Streets Wine Bar on Hardman Street with my mum, and Avril. A family dinner at the Berni Inn? A fish and chip supper, at home? Oh no, not for the Avril mini-me.

Streets Wine Bar was in what mum and dad called “our end of town” (as opposed, I think, to what they probably saw as the banal, less salubrious city centre?), down the little cobbled side road off Hardman Street adjacent to the bigger, buzzier Kirkland's Wine Bar. Streets was, in a way, Kirkland's slightly more sophisticated cousin: more of an intimate bistro than a big, spacious bar, with paintings by local artists on the walls and lots of actual local artists at the bar. Streets was also, in its own way, the Liverpool version of Langan's: 'trendy' at exactly the same time as the hip and happening Mayfair hangout it may or may not have been attempting to emulate, and attracting the Liverpool equivalent of the boho/arty red-carpet clientele.

Wine – which Streets specialised in – wasn't yet my thing at the age of 15 (I made up for that later). But oh, the food! Glossy, tawdry-pink taramasalata; crispy, teeny-tiny whitebait, their teeny-tiny black eyes, gaping mouths and erect tails frozen in time in the heat of the deep-fat fryer, lending them an almost gothic demeanour. Pitta bread, fresh from the Greek deli on the other side of Hardman Street. Real fish soup served with intriguing little pots of golden, garlicky mayonnaise, crunchy croutons, and waxy gruyere cheese that nobody quite knew what to do with; king prawns, still wearing their pearlescent suits of armour, accompanied by a finger bowl. Exotic food. Sophisticated food. Grown-up food... food that I was confident Avril would approve of.

Mum and I took to a heavy oak table in the split-level dining area. We ordered taramasalata, pitta bread and whitebait to share, and a bottle of Asti Spumante (this was long, long before any of us had even heard of Prosecco) that I had a small glass of before reverting to Coca-Cola, which we never had at home. I lapped up the taramasalata but had to force myself to eat the whitebait; those dead but still-staring eyes made me feel so sad, but I knew that it was the kind of dish that sophisticated people ate, so on I crunched, being brave. The owner of the restaurant brought me a rose that swiftly faded into insignificance as Avril made her entrance, bringing a cloud of cigarette smoke and Shalimar to the party. Avril smelled of grown-up.

By 9pm, the bar area had filled with young couples who looked like extras from a Roxy Music video, women who looked like Rula Lenska in Rock Follies, and art-school lecturers, hammered after a long afternoon of drinking whisky in Ye Cracke when they should have been hosting tutorials. I wanted to stay at our corner table forever, just watching and watching and watching, and trying to Learn How To Be Avril who, having included me in adult conversation all evening without ever condescending to teenage sensibilities (topics: Lou Reed's new album; what a crap book The Thorn Birds was; her husband's latest infidelity) had drifted off to mingle with the art-school cognoscenti. But time was running out if mum and I were to catch the 73 bus home – which we had to do, so we did. I bought Lou Reed's new album the very next day, but didn't see Avril again for many years.

Just a handful of short months later – eight, nine? – I was back in Streets sitting at that very same table, with my very same mum, watching my parents looking each other in the eye from a distance as Chicago's biggest and best weepy ballad “If You Leave Me Now” wafted through the speakers. Too late, Peter Cetera; by that time, they'd long since left each other – and that's when I had to start being a bit more Lily (or even more Dead or Alive frontman Pete Burns, whose legendarily fierce persona owed far more to Liverpool Women than you'd imagine) and a bit less Avril in order to do what Liverpool Women do best: survive on my own terms – and have a blast doing so.

There may be plenty of truth behind the mythology of the Liverpool Woman, but much of that 'truth' is as fake as the eyelashes, the lips, the tans. Motivation, strength, resilience, pride, intrepid entrepreneurship, passion without compromise – these are the actual qualities that actual Liverpool Women are made of. I'll be doing my sixties my own way, with a bold, proud inheritance to celebrate every step of the way.

Comments

Latest

And the winner is...

Losing local radio — and my mum

A place in the sun: How do a bankrupt charity boss and his councillor partner afford a “luxury” flat abroad?

Gritty, cheeky, sincere: How Martin Parr captured the spirit of Merseyside

The unbeatable, unforgettable Liverpool Woman

‘The real Lilys didn't really 'do' age; instead they did rage, wit, and defiance’