The Resurrection of St Julie’s: How a Catholic school in Woolton bounced back from a negative Ofsted result

‘We’re not an exam factory. Our primary purpose is instilling our girls with core values’

Kate McCourt couldn’t believe it. Not in that moment, and not for a long time.

Now deputy head, Kate had taught at St Julie’s Catholic High School for fifteen years. A Woolton village girls’ secondary that had nurtured such alumni as Hollywood actress Jodie Comer, songwriter Chelcee Grimes, and world champion athlete Katarina Johnson-Thompson, St Julie’s had always enjoyed a great reputation. Their previous Ofsted inspection in 2012 had duly returned an enviable “Good” rating.

But four years later, Ofsted had returned, and a very different judgement was in:

“Requires Improvement.”

For the uninitiated, that doesn’t sound so bad – almost encouraging. Anyone working at the coalface of education, however, knows that despite the four Ofsted categories – ‘Outstanding,’ ‘Good,’ ‘Requires Improvement,’ and ‘Inadequate’ – the true outcome is binary. Either your school was a credit to the community and a stalwart guardian over its children’s futures, or it was failing. You were failing. “Lose a ‘Good’ rating, and you may lose your career,” as Polly Toynbee wrote earlier this year.

Kate was sat with the head teacher, Tim Alderman, when they got the news. From the first day of the inspection, the tone of the feedback had tipped them off that not all was going to plan. Now the report was before them, in clear black and white, putting their school and all their teachers in the red. And yet, both Kate and Tim were in denial.

The report was wrong, they agreed. Ofsted was wrong. Nothing needed changing.

Again, workers in education will empathise with this attitude. The relationship between teachers and the review board around the UK is all too frequently an antagonistic one, if not openly adversarial. Teachers will attest to the stress leading up to a visit, and the trauma of the aftermath. When I started looking into this story, a teacher at a different school recounted a screaming match with an Ofsted inspector who, in her view, had done nothing but “pick holes” in her science lesson. Recently, this stressful process for schools had tragic consequences. Just last year, an inquest ruled that a 2022 Ofsted inspection had contributed to the death of headteacher Ruth Perry. Ms Perry, 53, took her own life months after Caversham Primary School in Reading was downgraded from “Outstanding.”

A testament to this psychological crucible, Kate and Tim’s period of nonacceptance vis-à-vis the results lasted weeks. “Then, it became a catalyst,” she tells me.

I arrive at St Julie’s on a crisp early-autumn day. Now the headteacher, Kate meets me with a smile and a firm handshake. Tim—now enjoying retirement, but kind enough to visit — happily shows me the peace garden’s olive trees. Woolton’s early-morning mist has thinned, but droplets of pellucid dew still cling to spider webs between the leaves. The school is now rated “Good” by Ofsted and, sat on the benches among the olives, it’s hard to believe it was ever anything but.

A major factor in their turnaround: researching the work of Barak Rosenshine. An educational psychologist from Chicago, Illinois, Rosenshine passed away in 2017, but he lives on in the form of the pedagogical system he’d created. By 2018, educational consultant Tim Sherringham had called Rosenshine’s principles of instruction “THE must-read for all teachers.” In 2016, though, Rosenshine was obscure to St Julie’s. Nevertheless, his work made sense to Tim.

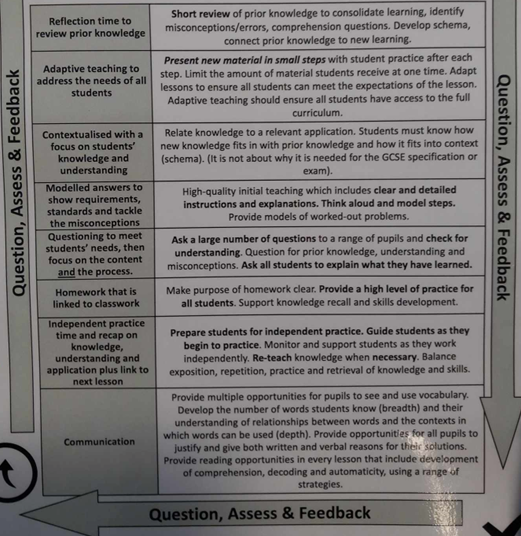

Rosenshine’s core idea was to prevent cognitive overload. “Just the same as adults —children can only retain so much,” Kate says. Rosenshine recommended ten principles for educators to avoid pupils being swamped by the material. “We began to implement approaches such as scaffolding the question,” Kate says. This involves supporting the students until they are confident enough to pursue the topic by themselves, with the goal of turning them into successful independent learners.

Another major issue cited in St Julie’s Ofsted report was inconsistency. Teachers were organising their lessons differently and using different jargon. Marking had no set standard. Adapting and simplifying Rosenshine – a psychologist by trade, not an educator – meant each lesson would now begin with reflection time, an opportunity for the class to review what had been previously covered before new material could be introduced.

Some teachers pushed back on the changes, disliking the sudden amendment to their tried and tested methods. But the new Considered Lesson Format was only a framework – it was down to individual teachers to imbue the lesson with their skills and personality. Over the next twelve months, the faculty worked together to implement the changes.

Their overarching goal was to move from imparting information to building understanding. Tim deploys some analogies to illustrate the intended development. “Teachers just delivering knowledge is a little bit like a Parcel Force package,” he says. “Someone comes to your door and hands over your parcel: ‘I have delivered your knowledge.’ But you have no idea what’s in the parcel or what it’s for. The next stage is becoming more like an IKEA shopper: you know the package contains a set of instructions and learn that there’s a particular sequence to follow to assemble the contents. But if you miss a step, the entire structure is going to be shaky.”

The final stage, then? “A Rolls Royce engineer. You know that if that little tube doesn’t get replaced, it’s going to have serious consequences further down the line. You understand every little step in building that engine.” Tim is an adherent of constructivism, the theory derived from Swiss developmental psychologist Jean Piaget that suggests children do not learn passively, but acquire knowledge through active involvement, with their own experiences, background, and worldview playing a part. “We can be knowledgeable with another man's knowledge, but we can't be wise with another man's wisdom,” Tim says, quoting Montaigne.

Two years later, the new approach was vindicated: Ofsted’s 2018 inspection restored the school’s ‘Good’ rating. Interestingly, the report cited social justice and the school’s ethos as the principles that drove the improvement: “Pupils’ spiritual, moral, social and cultural development is at the heart of all the school’s work.”

For other schools considering adapting Rosenshine’s principles, the great thing about the Considered Lesson Format is that it’s widely applicable. What might not be is St. Julie’s approach to faith. David Blunkett famously once said he wanted to bottle the ethos of religious schools, the better to distribute it among non-denominationals. How much did that culture play a part?

Massively so, Kate tells me.

She lifts her lapel and shows me a dark blue and silver badge adorned with six words: FAITH, TRUTH, JOY, LOVE, JUSTICE, HOPE, values she stresses can be valuable for girls regardless of their own personal religious beliefs. On the phone, she had also explained to me the importance of fostering a warm and caring environment for the students. “I may be biased, but I think our pastoral care is second to none.”

Tim shows me the archive library of the Sisters of Notre Dame—a relic from St Julie’s time as a convent school. He commissioned the angular, caramel-brown bookshelf built from olivewood to match the trees in the peace garden. They contain a collection of writings by Julie of Billiart, the school’s foundress and the patron saint of educators. Her story, like those of so many venerated peoples in the Catholic faith, is one of healing, rising: a novena to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is said to have precipitated her walking again after 22 bedridden years. Tradition is important to the school’s leaders, but only if it provides the pupils with a sense of continuity and the comfort that brings.

Kate’s comment about exam factories will resonate with many educators and parents. In 2018, 92% of teachers and 76% of parents in the UK blamed the pressure placed on schools to deliver good exam results for limiting the curriculum. According to the NHS, the prevalence of a probable mental disorder in children in the 8- to 16-year-old bracket rose from 12.5% in 2017 to 17.1% in 2020. The Good Childhood Report by The Children’s Society concluded that children’s average happiness with their school, schoolwork, and life as a whole was lower in 2020-21 than at the start of the survey in 2009-10, with the data suggesting that the wellbeing of girls requires the most attention.

Meanwhile, teachers have been asked to do more with less. According to the NASUWT, the second-biggest teachers’ union in the country, “the Tories’ decade of austerity, pay freezes and below-inflation pay awards have had a devastating impact on teachers’ take-home pay,” with nine out of ten teachers worried about how they’ll cope financially. A 2023 workforce survey by the Department for Education found that a record number were leaving the profession.

In the light of this staff retention crisis, the new government has pledged to recruit 6,500 new teachers. But disputes over pay and conditions look set to continue. After strike action and negotiations, the National Union for Education are recommending their members accept a 5.5% wage increase for all teachers across England, still well below the 10% claim the three recognised local government unions (Unison, GMB and Unite) submitted for 2024/25.

Headteachers have felt the pressure, too: a real-terms pay-cut of 15% over the past decade. Almost half of school leaders polled by the National Association of Head Teachers in 2020 said they were intending to quit their jobs prematurely. I fleetingly wonder if Tim was always so relaxed as he seems in retirement.

Will the new Labour government’s determination to scrap the old one or two-word Ofsted grading system make a difference? "The new Chief Inspector appears to be listening to leaders and schools about the uniqueness of their setting and context to the local area,” Kate says. “We did recently partake in a pilot inspection, and the attitude was much more ‘professional to professional.’” Less adversarial? “Definitely. There was more equality, it was much more constructive and collaborative.”

I leave St Julie’s as the buzz and chatter of breaktime ends. The late morning sun has begun to dispel the dewy mist, putting a silvery crease to the olive leaves. The girls have returned to their classes, and the grounds are calm again – a welcome tranquillity sadly unrepresentative of the state of education in this country. After 14 years of neglect, teachers and school leaders on Merseyside and beyond need all the help they can get. St Julie’s may or may not provide a model for schools looking to improve within the present educational framework. Without more funding, better salaries, and less pressure on individuals and institutions, however, schools will continue to fall behind, and children and teachers alike will continue to suffer.

Comments

Latest

Northern Powerhouse Rail is back on track. We think...

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still plays every Saturday

Does Liverpool have a ketamine problem?

The Resurrection of St Julie’s: How a Catholic school in Woolton bounced back from a negative Ofsted result

‘We’re not an exam factory. Our primary purpose is instilling our girls with core values’