The Parish Council, the mega-shed and the crucial flaw in Liverpool’s Freeport strategy

What the 20-year battle between Halebank and Halton Council tells us about a scheme designed to ‘add £850m to the local economy’

“It’s the size of six football pitches,” explains John Anderton, Deputy Chair of Halebank Parish Council, as he points to the 20m plus elevation looming ominously over the neighbouring suburban housing in Clapgate Crescent. The structure in question is what is known in the property industry as a “mega-shed”: half a million square feet of warehouse space designed to meet the needs of an as yet unspecified logistics operator. If our insatiable appetite for consumption comes with costs, then these architectural monsters proliferating around our motorway junctions and transport hubs are one of them.

The building is also the first visible manifestation of Liverpool City Region’s much-vaunted Freeport and the culmination of a 20-year-long planning battle between a village community and their local authority. It may also seem like a textbook validation of Sir Keir Starmer’s determination to dismantle a cumbersome and obstructive planning system and vanquish the nimbies and blockers who hold back development and thwart economic growth.

But for the residents of Halebank, a village on the outer edge of Widnes, the development raises different questions — how and why is it acceptable to locate a structure of such gargantuan scale on a greenfield site so close to a residential community, and is it justified that a development delivering relatively marginal economic benefits (200 mainly low skilled jobs) is attracting a generous package of financial incentives and tax breaks designed to bring high value, high-skilled employment to the City Region?

Halebank is not an affluent place, its predominantly working-class community hardly conforms to the popular image of the well-heeled Nimby. To describe it as close-knit would be more than a mild understatement. Despite the inexorable encroachment of Widnes’ urban industrial sprawl, it remains and is determined to remain, a village. It’s a place where people are all too aware of the need for investment and job creation. Only a matter of weeks ago, Metsa, the Finnish-owned timber importing and processing business, closed its nearby facility, transferring its entire UK operation to Boston, Lincolnshire.

So when, back in 2003, Halton Council outlined a proposal in its Local Plan to release greenbelt land east of the village for a “strategic employment zone”, they probably thought it would be welcomed. But they were very wrong.

Halebank’s industrial estates have historically been havens for what is sometimes euphemistically termed “non-conforming uses” — waste processing, skip hire, scrap yards, and metal bashing activities generally not tolerated within primarily residential communities. Most of the village falls within the COMAH (Control of Major Accident Hazards) zones for two top-tier hazardous chemical plants. Halton Council’s plans effectively meant the village would be surrounded by industry.

“They were taking away the one thing that local people valued most,” says Bernard Allen, former Chair of Halebank Parish Council. “Our greenbelt.”

Allen is Halebank born and bred, a stalwart of village organisations. He was instrumental in setting up the village’s Parish Council in 2008. “I think people had reached a point where they’d simply had enough,” he adds. “It was time to fight back.”

And so began a planning battle that would last the best part of two decades, including the excitement of two Judicial Reviews, three Public Inquiries and a cameo from the future cult heroine of all Parish Councils (one Jackie Weaver). Most importantly though, it’s a saga that underlines a crucial flaw in the strategy behind the Liverpool Freeport — an massive scheme that will apparently “add £850m to the local economy”. But more on that later.

As well as the “strategic employment zone”, Halton’s plans also envisaged an access road across the village’s only green recreation space created 20 years earlier on the site of a former scrap yard. For the community, the proposal had a galvanising effect. They petitioned to have their park designated a Village Green and were successful in thwarting the access road.

Next, the fledgling Parish Council tooled up for the Local Plan Inquiry with legal representation to argue for the strategic importance and value of the greenbelt. Well, that was the plan. At the inquiry, they were wrong-footed by a subtle manoeuvring of the goalposts. Accepting that the land did in fact serve an important greenbelt function, Halton Council now argued its location, adjacent to the West Coast Main Line, gave it unique potential as a site for a multi-modal logistics hub. It was imperative, they said, that the UK shifted freight from road to rail, and the site, now branded 3MG (Mersey Multimodal Gateway), would be a perfect location for a facility that would achieve this vitally important national objective. The Planning Inspector concurred but with two important conditions — only rail-served facilities could be built on the site, and the greenbelt land could only be developed when nearby brownfield land had been exhausted.

When Halton Council approved plans from US logistics giant Prologis in 2011, for a million sq ft mega-shed on the site (widely suspected to be on behalf of Amazon), Halebank’s Parish Council once again prepared for conflict on the battlefields of hyperlocal planning policy. Not even a generally negative assessment of their prospects from the as-yet-little-known Chief Officer of the Cheshire Association of Local Council, Jackie Weaver, could deter them. Not for the last time, Weaver’s authority had been questioned.

The High Court hearing was rich in drama and comic detail as a tiny Parish Council pitched battle with a well-resourced Unitary Authority and a global development company. At one point the presiding judge compared Halton’s arguments to the celebrated Morecambe and Wise / Andre Previn sketch, observing that they may well have considered all the right planning policies, “but not necessarily in the right order.”

Halebank’s victory, arguing that Halton had disregarded its own planning policies (the development was not rail-served and the brownfield sites were still undeveloped), was historic. It elucidated the scope of the arcane legal principle of “Wednesbury unreasonableness”; and seemingly raised the bar to an appropriate level for development on a site that was both strategically important and environmentally sensitive. When French rail company Alstom proposed its train modernisation facility on the site in 2017, the community was willing to accept a proposal predicated on the site’s rail connectivity and promising high-skilled, high-value jobs for local people (though in reality many of the jobs in the relocated facility were taken by existing employees from the company’s former site in Fylde).

But just when people in Halebank were looking the other way, the bar was subtly and decisively lowered. In 2020, planners quietly revised policies for 3MG’s former greenbelt sites as part of Halton’s emerging new Local Plan.

Notwithstanding the vital importance of the site’s location, and the urgent need to encourage a modal shift of freight from road to rail, development on the site would no longer need to be rail-connected. “We took our eye off the ball,” explains Anderton. “It was only when the planning application for the mega-shed from Marshall CPD came in that we twigged that policy had been changed.”

Indeed, when the mega-shed application arrived, the hardy Parish Council had finally run out of road. They could only object to a policy–compliant application on minor technical grounds, like an hours-of-use condition given its closeness to housing. But even these objections were not uptaken. “When Halton first proposed this kind of development on this site, we looked around at similar projects and sheds being built in St Helens, Warrington, and further afield,” says Anderton. “But we couldn’t find anywhere with buildings this size so close to established housing. There has to be a reason for that.”

For Halebank, it’s a battle lost and for Halton, it’s testimony to their resilience and ingenuity in finally delivering a scheme that they’ve been promoting for the last two decades.

At this point in the story, you might have an obvious pressing question: what does any of this have to do with the Liverpool City Region Freeport? Halebank, is, after all, not located in or especially close to the actual port of Liverpool. But geography is a fairly elastic concept in the context of UK and international freeports.

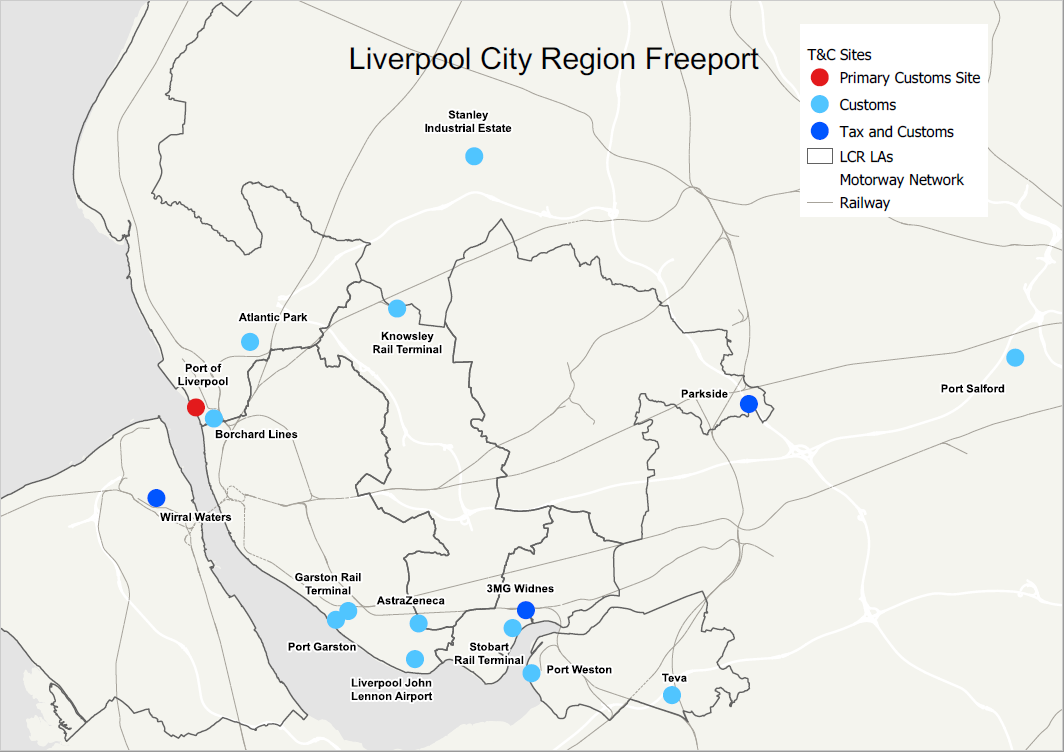

Freeports were one of the many schemes, structures, and devices conceived by the last Government under its rather nebulous and generally unsuccessful “Levelling Up” agenda. They are a far from transparent concept. Freeports are a type of Special Economic Zone located in coastal areas where customs, tax, and planning incentives are in place to encourage investment and economic growth. In the Liverpool Freeport area, these incentives include business rate relief, stamp duty and land tax exemptions on specific sites including Parkside (St Helens), Wirral Waters, and 3MG at Halebank.

If the geography and mechanics of the Liverpool Freeport sound a bit opaque and amorphous, the underpinning objectives are clear enough, and the potential benefits have been emphatically endorsed by Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram. In the foreword to its Prospectus, he declares that “by grouping high-productivity and innovative businesses close together”, the freeport can play a role in the region’s work to tackle weaknesses in the local job market such as productivity, pay and job security”. It goes on:

“These include innovation in advanced manufacturing, pharmaceuticals and green energy — with a particular focus on the region’s target to be net zero carbon by 2040 at the latest. We want to use the freeport as a springboard to develop our underlying strengths, providing more lab space and enabling the sort of cross-pollination that will see R&D flourish and innovation come to the fore.”

This is inspiring stuff and the underlying objective to diversify the City Region’s economy and stimulate growth in areas that will deliver higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs is both necessary and commendable. So how does this relate to a mega-shed on the outskirts of Widnes? The designation of 3MG as one of the Freeport’s three “Tax Sites” (benefitting from business rates and stamp duty exemptions) explicitly cites its connection to the rail network and its “involvement with then hydrogen economy” (Alstom are leading research into hydrogen-fuelled trains) as justification for its status.

But crucially, the logistics mega-shed approved by Halton isn’t rail-connected, nor is its future use restricted to businesses operating in the Freeport’s priority sectors.

Logistics and distribution facilities are of course an integral element in the ecology of the Freeport, but isn’t it rational to assume that these facilities should be located close to and integrated with the manufacturing and innovation hotspots that are its primary economic assets? Nothing of this kind ilk exists within MG3.

Both the Institute of Fiscal Studies and The University of Liverpool have published reports highlighting the risk that Freeports could simply become agents of “displacement”, where existing businesses move into the area simply to access the financial benefits, or “deadweight” where developments that could easily have happened elsewhere secure the benefits at the expense of genuine innovation. To this end, the UK taxpayer is subsidising businesses which do not serve the benefits of the freeport at the potential expense of those which do.

Anderton is perhaps not alone when he poses the question: “Why does an almost identically sized mega-shed a few miles down the road not get the same subsidy when its economic and employment impact is virtually identical?” His views are echoed by a highly experienced development professional who has operated in the logistics and distribution sector for over 30 years. Unwilling to incur the wrath of the region’s local political establishment, he privately sees the Freeport as exercising a distorting impact on the market, making it more difficult for him to sign end-users for buildings outside the privileged “Tax Sites.”

But for the Leader of Halton Council, Mike Wharton, the development and the Freeport designation are crucial to the Borough’s economic development ambitions: “Halton’s Economic Growth Plan (The Mersey Gateway Regeneration Plan) is predicated upon the development of land and sites to create jobs and bring wealth to the local economy and our communities,” Wharton told The Post. “We believe that being part of the Freeport will help to accelerate these benefits by allowing Local Authorities to offer financial and tax incentives aimed at encouraging businesses to invest in the area.”

He further cites a “robust Gateway Criteria Policy” that requires businesses to demonstrate how they will add value in sectors that are important to Halton’s long-term economic prospects. Notwithstanding Wharton’s defence of the project, it remains difficult to see how a mega-shed in Halebank is more integral to the operation of the Freeport than those at Omega (Warrington), Knowsley, Haydock or Speke?

The fractured nature of the Liverpool Freeport, compared with the more geographically focused and coherent model in Teesside, together with the absence of transparent governance and scrutiny structures, only reinforce concerns that this is not so much a joined-up vision, as a badge to repackage longstanding priorities and pet schemes.

With Keir Starmer promising to “turbo-charge” the City Region’s economy, it will be interesting to see where or whether the Freeport, and other relics of the ancien regime, fits into the architecture of Labour’s new dispensation. For Steve Rotheram it appears to remain a pivotal component in his recently announced four-year plan to grow and transform the region, but it must quickly prove itself to be a vehicle capable of delivering the quality of development, innovation, and jobs that are not yet evident at Halebank.

Whilst visiting Clapgate Crescent, to judge firsthand the imposing impact of the structure on its neighbours, I got into a conversation with a resident on his lunch break. Darren had started his new job at a local business that week following his redundancy from the recently closed Metsa site. In the meantime, he had worked shifts at the Amazon facility in Warrington packing vans for dispatch. Reflecting on his recent experiences in the world of logistics mega-sheds, and pointing at the offending edifice, his judgement was brutally blunt. “I wouldn’t want to work there.”

Comments

Latest

What “Your Party” could mean for Liverpool

Birthday, la! The Post is five years old

Cast, the Scouse underdogs bringing guitar back

Have Sefton’s children’s services really improved?

The Parish Council, the mega-shed and the crucial flaw in Liverpool’s Freeport strategy

What the 20-year battle between Halebank and Halton Council tells us about a scheme designed to ‘add £850m to the local economy’