The heart of the city is no longer for music — it’s for stag dos and brunch

Why has clubbing been pushed out to the periphery?

Some of my most vivid memories of childhood are from the back of my dad’s car, specifically on the way back from Great Harwood, a small town near Blackburn where my grandparents lived. It makes sense that I remember these moments so clearly, given that it was an established format repeated many times. We’d go there on a Sunday, maybe once a month, and leave in the early evening to head back to the Wirral, while me and my sister drifted in and out of sleep with China Crisis or New Order blasting out of the stereo, more or less the only bands we listened to on the motorway.

Like many families, music was a big part of our lives. My favourite song when I was seven was “True Faith”, which sounds cool now but wasn’t then. In terms of the way I write music or approach melody, those childhood years were incredibly formative and potentially also a reason why one of the things I love most is driving through darkness on the motorway.

At the beginning of secondary school I started to experiment with my own taste, which ranged from things like Dr Dre and NWA, Limp Bizkit and Slipknot, to Blur and the Manics. But I also became aware of dance music, Scouse House, trance, and older lads heading off at the weekends to Wigan Pier. These tunes were also often played on the coach to Tranmere away games, where I had a season ticket from around the age of 13. Crucially, girls seemed to like this sort of music too.

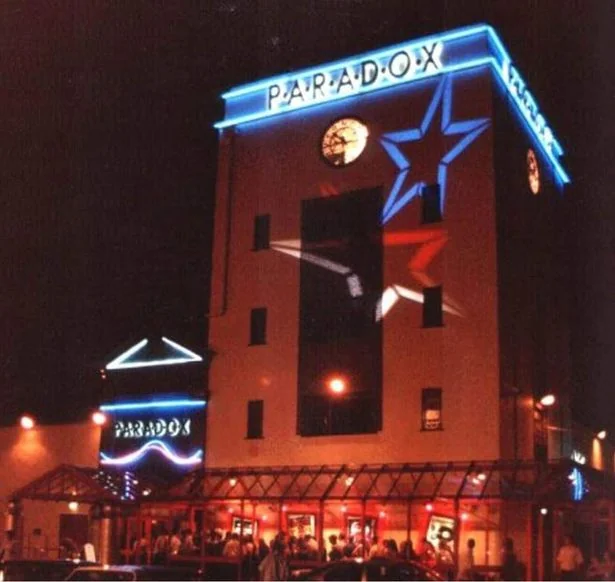

Often on a Saturday night I’d stay at a mate’s house close to mine and we’d record Radio City 96.7, which broadcast Kev Seed and Nigel Evans DJing from inside The Paradox, a long-knocked-down nightclub in Aintree, with those cassettes becoming the school bus soundtrack for that week. It was a very early entry point into a form of mixtape culture, but also my first real understanding that nightclubs existed, that people went out late at night to listen to DJs.

My curiosity was piqued, especially given that on those drives back from Blackburn we’d go past The Paradox: a foreboding, boxy, obelisk-like art deco structure I’d seen many times but never really noticed. Now I knew what happened there — or, at least, could imagine something close to what it was like.

By 16, I was going out in Liverpool to psytrance nights because they were the only places we could get in. The music makes me wince now, but it was a welcoming, safe introduction to clubbing, whether we were at the Zanzibar for Alien Resonance, or Fort Perch Rock in New Brighton for Ultra Violet. I think I told my parents I was going to science-fiction nights, which has a grain of truth to it, however tiny.

But it was when I enrolled at Liverpool Community College that my “town” era really kicked off. Given what’s on offer in the city centre now (more on that later) it’s almost strange to look back at what was happening in Liverpool twenty years ago. Via the Wayback Machine I pulled up an old Outlar (the city’s once essential, now defunct dance music guide) listing from October 2004. In the space of just over one week, venues in the city centre welcomed DJs like Andrew Weatherall, Erol Alkan and Frankie Knuckles, alongside a raft of regular events throughout the week hosting local residents, all geared towards music.

This culture and infrastructure was built on Liverpool’s globally renowned nightlife, a phenomenon that exploded in the mid-90s via Quadrant Park in Bootle and Cream in the middle of town, Meccas for British clubbers and people around the world. It’s hard to make the case that Liverpool offers anything cultural now that people would travel to the city centre for beyond The Beatles. At a push, the Tate and the Phil. But certainly not anything contemporary.

I moved back to Merseyside three years ago after nearly a decade living in London. Consequently, the difference in Liverpool’s city centre is stark to me. What was once a concentrated ecosystem of venues mere yards away from each other has disappeared, artists and promoters edged out to the docklands. Korova shut in 2006 before relocating to Hope Street, but two years later the Kazimier opened on Wolstenholme Square, metres away from Mello Mello and Wolstenholme Creative Space. As is the modern way, the Kazimier was bulldozed in in 2016 along with Nation – the original home of Cream – to make way for apartments and “commercial enterprises”. Hallowed afters spot the Magnet is gone too – I had the best night of my life one New Year’s Eve in there watching legendary Chicago house DJ Derrick Carter. Now, there’s Arts Bar, Jacaranda, and The Zanzibar has also reopened, but there’s a noticeable difference in the way the city centre even sounds today, no longer truly a place for music.

Now, I look back and realise how much the intimate geography of the city centre influenced me artistically, and so many other musicians. It was common to go to three events in one night, because it was cheap and venues were situated so close to each other. My previous band Outfit played its first show in Wolstenholme Creative Space, which was an art gallery. I spent as much time attending or playing noise shows as I did at techno nights. The synergy between the city’s different scenes was extremely tight and the overlap between them natural – The Kazimier was as much an art project as it was a music venue, while Wolstenholme Creative Space hosted exhibitions and put on plays alongside punk shows. They were halcyon days when the centre of the city felt dominated by the arts, guided by the buildings that housed it, and perhaps a period when it lived up to its “Capital Of Culture” status.

I made friends I still know now in these places, and went on to work with many of them. The reality is that government cuts have hugely exacerbated the issue – Mello Mello on Slater Street applied for discretionary business rate relief in 2012, struggling to deal with rocketing rents, but was turned down by a council forced to put money elsewhere. Forgive me if this is rose-tinted, but I do strongly believe that young people need easy access to art and self-expression beyond the algorithm-dominated internet of today.

It’s true that Liverpool now competes with any city in terms of food. Its pubs are the best in the country, and there are exciting rappers emerging like EsDeeKid and Mazza, which is a new sound for the city, but for a place whose calling card has long been culture, the centre of town now seems geared towards something else entirely. There are relatively new, great venues on the docks – we’ve thrown Crack Copies parties at Quarry, a venue we love, and we played a God Colony show at last year’s New Year’s Eve party at the Invisible Wind Factory, which was everything we like about playing clubs – dark, sweaty and a crowd of really up-for-it punters. It’s a brilliant club, run by brilliant people. But these places on the shadowy outskirts also exist as a reminder that the heart of the city is no longer for music or culture, and more for stag dos and brunch. Culture being forced out into the periphery of the city makes it harder for different people and social circles to overlap, or scenes to cross-pollinate – you’re more likely to stay in one place for a night if you have to get a cab rather than just walk.

God Colony didn’t form until we both moved to London, but we became friends when we were 18 or 19 and still in Liverpool – I was in a few bands and James was a resident DJ at Chibuku. He’d often be playing sets in the same venue after gigs I’d played, particularly at EVOL in Korova. It was natural that we met and we bonded quickly over Kompakt Records, Erol Alkan and the dance music blog Keytars & Violins. I’d go and see him play most weekends. When we were about 23 we moved into a big house on Ullet Road called “The Lodge”, with around 20 other people and did all the obvious things you’d do with that amount of space and cheap rent – throw parties and make music in the basement. “The Lodge” is empty now, its decaying frame now rummaged through by urban explorer YouTubers and it actually appeared on TV recently, used for a scene featuring an abandoned house in BBC One show The Responder.

We released the first God Colony tunes in 2015, working with Flohio and Stash Marina, rappers from South London and New Orleans respectively. Those early collaborations were really influential for us – we’d gone from messing around making techno beats to working with rappers, something that was almost accidental but helped us make, in our opinion, really unique tunes. From then on, we worked with different vocalists from around the world, which led to us executive producing the Flohio album in 2021 and making a film soundtrack with Bobby Gillespie from Primal Scream the following year.

Both were great, absorbing projects to work on and they’re artists that we respect a lot, but we knew after Covid that we wanted to work towards a sound that was totally ours. In thinking about that, we went all the way back to where we met, going to see DJs like Marcel Dettmann and Ricardo Villalobos in Liverpool, which is where the title “North West Tonight” came from. We would never want to rely on nostalgia for the actual sound of our music, but we were thinking about the freedom, DIY spirit, and immense creativity of that time, in a city that was designed for it then. We wanted our record to feel like a night out in Liverpool, a futuristic utopia influenced by blurry memories of the past.

Rhythmically we’re not influenced by Liverpool I don’t think – certainly on this record those drum patterns are definitely inspired by global scenes like gqom, amapiano and baile funk – but melodically we take cues from Liverpool’s new wave and post punk era (in my opinion an overlooked part of the city’s cultural history and so while you’re reading here’s an NTS mix we made of our favourite stuff from that time).

All track titles are North West landmarks, some more recognisable than others, and final track “The Paradox” features Liverpool writer Roy appearing on a track for the first time, listing different, conflicted identities that are specific to Liverpool but relevant around the world. Being an artist in Liverpool circa 2006-2012 felt like a golden era, where you could hire a club in the city centre for fifty quid, bang decks in it and throw a party. That’s undeniably harder for people to do now. We wanted our record to capture some of that anarchy and the freedom we had, a confluence of styles but geared firmly towards the dancefloor.

Until it shut a year ago, I had a monthly radio show on Melodic Distraction, the Liverpool radio station off London Road that closed due to rising costs and fewer funding opportunities. I liked going to do my show and it kept me practised on the decks, but what I really loved about it was seeing how many people far younger than me were there learning how to DJ, how to broadcast, sharing tunes and hanging out. Its closure is definitely not an issue that’s specific to Liverpool, it’s across the country too. Still, I wonder if in reality it’s dining out on the successes of the past while ignoring what the future might look like.

North West Tonight is out now.

Comments

Latest

And the winner is...

Losing local radio — and my mum

A place in the sun: How do a bankrupt charity boss and his councillor partner afford a “luxury” flat abroad?

Gritty, cheeky, sincere: How Martin Parr captured the spirit of Merseyside

The heart of the city is no longer for music — it’s for stag dos and brunch

Why has clubbing been pushed out to the periphery?