The families on Merseyside who dread the approach of Christmas

'We are all about saying to kids: things can be different'

“Some kids will bring really big clothes, and we replace them,” he says. “People will bring towels that are appalling — so you replace them and give them new ones.”

When he first started out, what struck him when visiting families across Merseyside was the poor quality of the homes. Now that’s changed. He goes into decent houses that don’t have carpets or bedding. “Housing has improved dramatically, but what's inside hasn’t,” he says. “So we try to provide beds and clothing.”

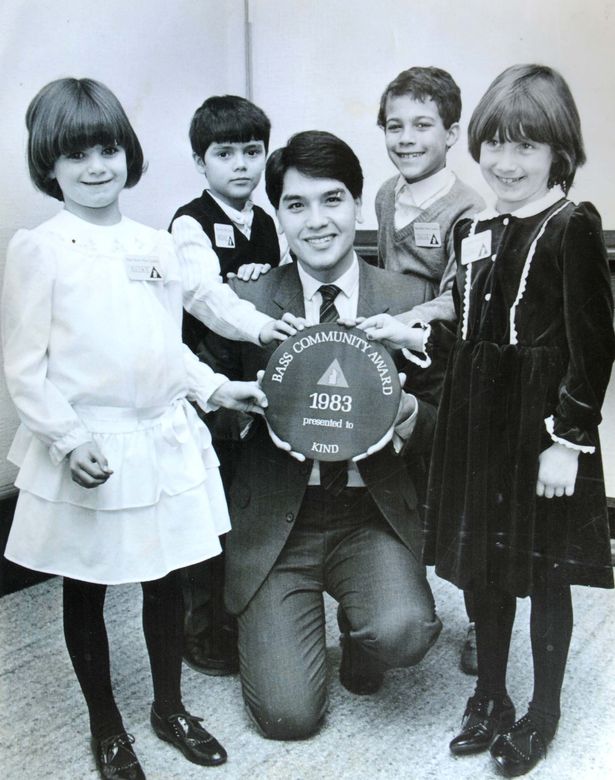

Stephen Yip, 65, has been doing it since 1975. In 2013 they granted him the Freedom of Liverpool, only the 63rd person to receive that honour since 1886. This year he is doing his 45th Christmas Appeal for his children’s charity Kind. Except this one is a bit more difficult. “This year I think we will get families referred to us who in the past would have donated to us,” he says.

Kind has its centre off the back of Canning Street in Liverpool’s Georgian Quarter, but the children come from all over the city region, including many from Knowsley and The Wirral. He notices that different communities deal with deprivation in different ways. “In some areas of Merseyside like St Helens they still have the traditions of you wear your hand-me-downs,” he says. Less so among families in Liverpool.

The charity has two qualified teachers and three qualified learning mentors, as well as volunteers and two new apprentices. “We have a lovely outdoor space — a dipping pond, a growing area, an allotment, we have four beehives,” he says, which produce “Bee Kind” honey. The emphasis is on giving the children affection and structure. “Children thrive when they are given recognition,” he says. “We are all about saying to kids: things can be different.”

Children from disadvantaged homes get referred to Kind if schools or social services think they could benefit from the charity’s extra educational support or its summer residentials. Yip and his team transport the kids to the countryside to take their minds off whatever is going on at home, and to give their parents a break too. And every Christmas he launches an appeal, that pays for large hampers filled with food and toys to be delivered to some of the poorest homes in this part of the country. “I feel that families struggle all year, so once a year they should get something special,” he says.

Last year the appeal raised £100,000. This year fundraising has been much more difficult because of the pandemic. He’s aiming for £50,000 instead. “We don't get any big grants,” he says. “We rely on small donations from individuals.” Kind is a small charity and it’s been run responsibly for decades. “We don't have PR or paid fundraisers, so it's hard,” he says. “We have a loyal band of supporters. People know if they fund us they get value for money. Every pound donated is a pound spent.”

His brother is David Yip, the actor who played CIA agent Chuck Lee in the 1985 James Bond film A View to a Kill. They grew up on Duke Terrace, just by Chinatown, a street that had some of the last back-to-backs in Liverpool. Stephen was born in 1955 and was one of eight, sharing all six rooms of the house. “We were disadvantaged but everyone who lived by us was disadvantaged,” he says. “I didn't go on holiday until I was 15.”

The house didn’t have a bathroom, and the children bathed in a tin bath. “The youngest was the last in — they got the dirtiest water,” he remembers. Despite the circumstances the family lived in, he had “The best childhood ever,” he says. “We were fed, loved and looked after.” Years later, he would realise the importance of those gifts, and how many children are denied them. “That childhood gave me the values I use now — respect, responsibility, looking after yourself,” he told The Post.

His dad was one of the Chinese seamen who came to Liverpool from Canton (now better known as Guangzhou) in the 1930s. He was living in a hostel with other sailors when he met Yip’s mum, a Scouser. It wasn’t an easy time for a union like that. There was “a lot of racism around,” he says. “Her parents did not want her to marry a Chinese sailor.” His dad worked for the Blue Funnel Line and would away for months on long-haul trips, so his mum brought up the children.

As a result, the children didn’t speak Chinese. “That was very unusual,” he says. “We looked the part, we liked the food, but we didn't speak the language.” It was only when he passed the 11+ and went to the highly-regarded Quarry Bank High School that he realised “there was another world out there.” Out of 90 boys in his year, only he and one other boy were not white.

He founded the charity in his twenties while studying Social Studies at Liverpool University. He had tried out a variety of jobs, including one for the council and a very short spell in a high-flying sales role for a blue-chip firm. “My heart wasn't in it,” he remembers, although he admits he is “a good salesperson” and credits that skill with keeping the charity going for 45 years through numerous economic downturns.

How has his childhood in Liverpool informed the work he does? “My big thing is, education is the only way out,” he says. “That's how you escape.” He believes in Kind’s approach because he’s seen it work many times over. “A lot of the kids we have worked with have become teachers or social workers and have their own families and are doing really well,” he says. With other children, he is working with them having worked with their parents decades ago. “It's about telling them: there is a different way of life.”

Another legacy of his childhood is his focus on this time of year. He wants to pass on an experience he had. “Christmas was a special time for me as a kid,” he says, and now his focus is finding families - often single mothers with multiple children - who dread the festive period because they don’t have enough money to buy their children any presents, or any nice food.

“Every parent wants to do the best for their kids. It's very very hard if you are unemployed or you are on low income - how do you afford it?” He says he feels for mums whose kids are seeing endless ads on TV and YouTube promoting toys and presents that the family doesn’t have any hope of buying.

“I don't want families to go into debt,” he told me this week. “When I first started, I would work with mums who took out a ‘Provi loan’ in October and would spend the rest of the year paying it off, and then take out another one.” He says in the past few years some of the more predatory lenders have disappeared, but it’s still one of his biggest concerns at this time of year. “There are a million and one people who will lend you money. We tell families: don't get into debt — you won't get out of it,” he says. Hence the generously-proportioned hampers and the exhausting, relentless round of fundraising every year for the Christmas Appeal.

This year he knows he is up against it. In addition to the appeal, he is also looking for a 20,000 sq ft warehouse space to pack the hampers. “It's not just about the material gifts we give to these families. It's about the knowledge that other people in their community care about them, and they are not on their own,” he says. “In the year of Covid, it's so important that they know people are looking out for them.”

To donate to Kind’s Christmas Appeal, go to their website and type in your contribution.

Our Founder & Chief Executive, Stephen Yip introduces this year's KIND Christmas Appeal & explains how you can get involved.

— KindLiverpool (@KINDLiverpool) 8:46 AM ∙ Nov 1, 2020

Comments

Latest

I’m calling a truce. It’s time to stop the flouncing

The carnival queens of Toxteth

The watcher of Hilbre Island

A blow for the Eldonians: ‘They rubber-stamped the very system they said was broken’

The families on Merseyside who dread the approach of Christmas

'We are all about saying to kids: things can be different'