The Decline and Fall (and Rise?) of Mersey Culture

How to kill a city's art scene

Dear readers — In 2008, Liverpool was declared the European Capital of Culture, and in the sixteen years since, the city’s arts and music have experienced both ebbs and flows. In today’s edition, Laurence argues that we’ve only trended downward — and that’s the fault of local hubris, shortsighted urban planning, problems in national arts funding, and perhaps even a crisis in the wider cultural landscape. Plus, as always: the rent is too damn high.

Is there hope? Can we reverse this trend by looking at the historical examples of other cities? Read on to find out if the folk culture of Liverpool is due a Renaissance, or if the artistic achievements of the city’s people will become relics of a bygone era.

But first, your regularly scheduled briefing.

Your Post briefing

Severe flooding in Bootle has led to evacuations of people’s houses, while roads and rail services have also faced disruption. Merseyside Fire and Rescue Service say a number of properties on Bowles Street have been evacuated, with the crews of six fire engines helping more than 40 people from their homes. Seaforth Road and Knowsley Road were closed too, as was Queens Drive in the Mossley Hill area, where; in August last year, two people died after being trapped in their car by floodwater.

Chester Zoo has helped create a new UK wildlife sanctuary by planting around 19,000 trees in a low-biodiversity silage field. The zoo planted a new area of woodland across nine-hectares of unused field in Upton, Cheshire. The initiative, funded by the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) and delivered in partnership with the Mersey Forest, hopes to provide a "richer and more diverse habitat for a range of species" including green woodpeckers, badgers, harvest mice and butterflies, according to Dr Simon Dowell, director of science and policy at the zoo.

In an attempt to plug a £300,000 budget shortfall, Wirral Council is looking to start charging for parking at 22 car parks. Sean Martin, chair of the New Brighton coastal community team, said the charges were “short-sighted” and would prevent the town from prospering, while high-street traders in Bromborough Village anticipate the charges will be another blow to their businesses after the loss of banks, shops, and the town’s library and civic centre. The council’s environment and transport committee chairperson, Liz Grey, previously warned of "very difficult choices” on the horizon if car parking wasn’t subsidised “to the tune of £300,000 a year".

The Decline and Fall (and Rise?) of Mersey Culture

“We love the place we hate, then hate the place we love. We leave the place we love, then spend a lifetime trying to regain it. Between loving and hating, the real journey starts.” – Terence Davies, Of Time and the City

When I was not quite 20 years old and seething with late adolescent ingratitude, I saw Ringo Starr play on top of St George’s Hall for free and immediately wanted my money back. The feeling was mutual: when asked what he’d missed about his home city, Ringo replied, “Nothing.” Blinking into the firework dazzle as the ex-Beatle sang the sycophantic line “Liverpool, I left you, but I never let you down,” my mates and I somehow felt like the fatted calves for this simultaneously ingratiating and ungracious prodigal’s homecoming.

So went the 2008 European Capital of Culture celebration. This was my first exposure to Liverpool as a self-consciously creative city and the reason I reach for my revolver whenever I hear the word “culture,” as Herman Goerring never actually said, and my shotgun whenever I hear the noun “creative.” (As in, for example, “Baltic Creative,” the mortifyingly earnest entrepreneurial space founded for fledgling Scouse capitalists the following year.)

To a peculiar subgenus of Merseyside resident, though, the 2008 festival was what the 2012 London Olympics opening ceremony is to middle-class political centrists countrywide – a mythic, almost Arthurian moment of unity and the crucible of their spiritual formation. That subgenus is the Scouse Exceptionalist. He is for the most part a friendly zealot, whose complexion begins to tint first red and then blue, as if to not leave out either team, if you give any sign you don’t think Liverpool is not only the best city in the world but the best city imaginable – a Platonic ideal of music, theatres, pubs, football, museums, galleries, restaurants, football, political consciousness, humour, nightlife, and football.

In my experience, Exceptionalists tend to live outside the city and don’t consume a great deal of the culture they proselytise about. Nevertheless, to this strange but thus far harmless enthusiast, no criticism of the city’s cultural direction is tolerable because, indeed, the city has no direction: it exists outside of spacetime, a perfect crystal floating in eternity. Content warning: if you’re one of these people, this article may not be for you.

Unalloyed triumph or not, sixteen years later, I’m far from sorry Liverpool won this award, even though – with all respect due to the residents of Tartu and Bodø – subsequent laureate announcements have made that honour feel like a participation trophy. Regardless of its many merits, I’ve never been able to shake the sense that becoming the Capital of Culture was responsible for engendering a hefty dollop of complacency in both the council and the people, even if they aren’t quite the Exceptionalists I describe. The litany of vibrant music venues closed since 2008 – the Magnet, the Kaz, MelloMello, the Wolstenholme, Dumbulls, Nation, Fall Out Factory – is stark evidence.

One of the campaigners responsible for Liverpool’s 2008 crown was political strategist Jon Egan, now a valued contributor to these very pages. Egan recently wrote an essay in the Liverpolitan castigating Liverpool and its city council for prioritising the kitsch of Eurovision and Taylor Swift concerts over fostering authentic locally-grown folk culture like The Beatles. Perhaps because of my impressionable encounter with their erstwhile drummer, I’ve never quite been able to parse the “Fab Four” as a phenomenon from what Jon describes as the “anodyne mediocrity” of their packaging by the city’s culture industry, but regardless, Egan’s urbane and erudite arguments deploy both Marxist Clement Greenberg and agrarian pacifist Wendell Berry to persuasive effect. Egan’s piece inspired me to Leninist catechesis: what is to be done? How do we generate a vibrant, genuine folk-cultural scene, in Liverpool or anywhere else?

“If Liverpool did not exist, it would have to be invented.” So said the Austrian painter Felicien de Myrbach in 1898, staggered by the opulence of the British Empire’s second city. By the time Terence Davies quoted him a hundred and ten years later – in Of Time and the City, Davies’s elegiac love-letter to Liverpool – a sardonic tone had crept into the cadence. The Manchester Ship Canal, the Great Depression, containerisation, and the Thatcherite insanity of socioeconomic euthanasia had reduced the once-mighty port to a quirky appendage on the coast.

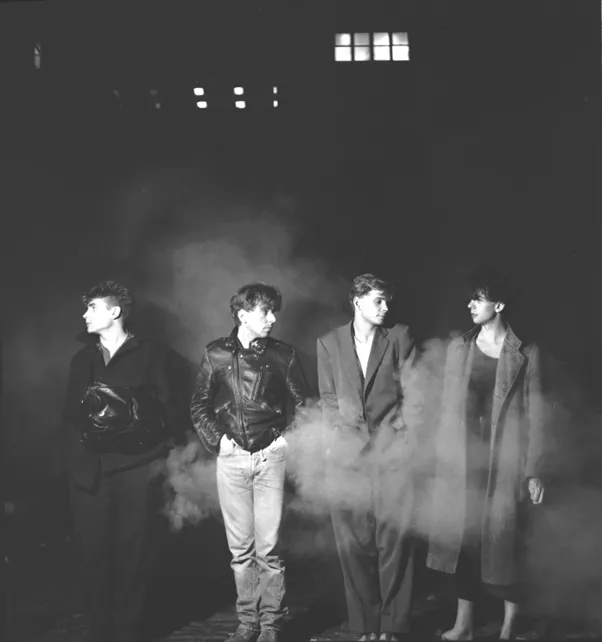

Nevertheless, considering its “managed decline,” it’s not unreasonable to argue Liverpool has often punched above its weight culturally. Bands like Echo and the Bunnymen and The Teardrop Explodes, poets like Adrian Henri and Malik Al Nasir, sculptors like Arthur Dooley, avant-garde theatre impresarios like Ken Campbell, authors like Ramsey Campbell (no relation) and Beryl Bainbridge, and scriptwriters like Alan Bleasdale, Jimmy McGovern, and now Tony Schumacher have belied the city’s apparent downfall. For the latter three at least, Liverpool’s economic decay even provided fertile soil for indignant, socially conscious art.

Some of these artists are mentioned in Egan’s essay along with the giant of literary Modernism, Wallasey-born Malcolm Lowry – who, as a Wirralian myself, I’m not quite willing to cede to the other side of the Mersey. Yes, they’ve been oases of inventive hope in a desert of economic deprivation, but it’s hard to see connecting streams. Excepting Henri and the other Mersey poets, Roger McGough and Brian Patten, most of these luminaries shone in isolation – perhaps befitting a city of individuality and eccentricity. Nonetheless, many British cities will be able to name comparative artistic talents.

What’s rarer is artistic movements. Here’s where we return to Teardrop and the Bunnymen, who did not spring self-created from a howling void but were part of a post-punk milieu inf(l)ected by late ‘70s Sex Pistols and Buzzcocks gigs at Eric’s on Mathew Street. This “second wave” of the city’s music also included Deaf School, Big in Japan, The Wild Swans, Wah! Heat, and the KLF, all memorialised in Teardrop and Swans’ co-founder Paul Simpson’s book Revolutionary Spirit. Andy McCluskey founded Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark just so he could play at Eric’s. A hundred yards from the venue was Probe, where you might have seen a 17-year-old Courtney Love necking cider on the steps or a backcombed Pete Burns menacing customers for browsing the wrong records. Love shared a flat with Teardrop co-founder Julian Cope and later said, “Before Liverpool, my life doesn’t count.” This was a scene.

But that’s all in the past. What about the future?

When Christopher Torpey co-founded Birkenhead’s Future Yard venue in 2020, he had McCluskey’s Eric’s confession in mind. “Why can’t we have that aim? Perhaps there’s a group of kids sat somewhere in Birkenhead, thinking: ‘Let’s form a band so we can play Future Yard,’” Torpey told the Guardian. Yet when I checked Future Yard’s listings for the rest of the year, I could only find three Merseyside acts, one of whom were Deaf School themselves, and none who debuted after Future Yard’s founding four years ago. The remaining taste-making venues across the Mersey – the Arts Club, Jacaranda, the Camp & Furnace – fare little better. (Forget about the so-called “Eric’s”, a pathetic and cringe-inducing exemplar of Heritage Liverpool no less anodyne than The Beatles Story or the two fake Caverns.)

Outside of the maturing Scouse Rap sphere of which I must plead ignorance, why haven’t we seen another DIY musical wave? Perhaps it’s too soon. Or maybe the environment just isn’t there.

“Where any view of Money exists, Art cannot be carried on,” said William Blake. But many of Simpson’s, Burns’s, and McCluskey’s generation went to university or arts school without paying a penny, while others had the state heavily subsidise their fees. To quote social theorist Mark Fisher, “most of the innovations in British popular music which happened between the 60s and the 90s would have been unthinkable without the indirect funding provided by social housing, unemployment benefit and student grants.” The initial countrywide outbreak of punk, not to mention glam and other pop genres, was the product not just of more generous budgets for local arts and drama projects but also affordable housing and the dole. The latter has often operated as an unacknowledged, under-the-table handshake between the state and prospective artists from less advantaged backgrounds.

An example from outside of music: the working-class graphic novelist Alan Moore, after suffering in a number of jobs including on a tanner’s yard and cleaning toilets, decided in 1977 he’d never work again, signed on, and adopted the nom-de-plume Curt Vile to give the benefits office plausible deniability. Doubtless the curtain-twitching post-Benefit Street denizens of Britain would be outraged to learn of someone drawing the then £10-a-week jobseeker’s from the state without actually intending to pursue straight employment. But if we must reduce creative works to their commercial value, those budding DWP sanctions officers should instead think of public assistance as investment — in Moore’s case, in someone whose imagination has, when adapted to the medium of film, generated literally hundreds of millions at the Hollywood box office. (Imagine if those adaptations had been A. funded in this country, B. made with the author’s consent, and C. any good.)

Moore is a singular visionary, an inheritor of Blake’s anti-tradition. But even if there was a budding Scouse equivalent, short of a dole-equivalent stipend rescuing them from the thresher of the universal credit that replaced it, would we even know about them now?

The preconditions for vigorous arts scenes have always been A. wealthy patrons, as in cinquecento Florence and Venice; B. cheap rents, like with 1960s Haight-Ashbury or the scene around New York’s Chelsea Hotel in the ’70s; or C. both – see La Belle Epoque, or the expatriate literary and arts community in Paris in the 1920s centred on Getrude Stein’s salon. In Just Kids, her New York memoir, Patti Smith recounts her exhausting but never unfeasible quests for affordable living in the Chelsea and elsewhere on her pre-rockstar shopgirl’s salary. In A Moveable Feast, his Paris memoir, Ernest Hemingway gives an (exaggerated) impression of cheerful poverty as a 22-year-old émigrée, his flat off the Place Contrescarpe costing only 250 francs, or $18 a month – the equivalent of around £250 Sterling in 2024’s money. Berlin maintained an alternative or avant-garde backdrop for so long through a rent cap and squatting.

Cheerful poverty is not an option for artists in 21st century Britain. If you don’t have parents wealthy enough to support you until you blow up, it’s nigh impossible to make a living in a band, as a writer, or creating art of any kind. Skyrocketing rents, a deluge of gig economy jobs, the commodification of higher education, and a surreal, psychopathically punitive benefits system the actor Julie Hesmondhalgh rightly called “Kafkaesque” means that embryonic bohemian lifestyles like Moore’s, Smith’s, or Hemingway’s are all but unfeasible.

Austerity has gutted not just this country’s infrastructure but also its soul. Young people work long hours at jobs so stressful and boring their brains are burnt out by five o’clock Friday, the weekend merely a time for mind-numbing (an)hedonism Kae Tempest ably evokes in “Europe is Lost,” a hip-hop lament for a generation crushed by the psychological pressures of late capitalism and a dying planet:

System’s too slick to stop working

Business is good, and there’s bands every night in the pubs

And there’s two for one drinks in the clubs

And we scrubbed up well

Washed off the work and the stress

And now all we want’s some excess […]

Half a generation live beneath the breadline

Oh, but it's happy hour on the high street

Friday night at last, lads, my treat!

Perhaps this speaks to me because, only two years younger than Tempest, I’m an ageing Millennial who’s done plenty of jobs that threaten to hollow-out the soul before spending evenings attempting to create something beautiful or interesting. As there aren’t many modern Medicis thirsting to drop millions on young Scouse poets or painters hanging around Liverpool’s business district – trust me, I worked there for the best part of a decade — the only solution is to alleviate the cost of living, studying, and/or making.

While it’s, alas, beyond the authority of local councils to set tuition fees, something could be done about rent. While Liverpool is not quite in the top ten most expensive cities to live, it’s a long way from Smith or Hemingway’s living conditions: according to the ONS, the average monthly private rent in Liverpool was almost £800 this year.

Using Berlin as an example, I’d almost be tempted to recommend squatting as a solution. In a response to rocketing London rents in the 1970s, poet Heathcote Williams ran an "estate agency" for occupiers. In 1977 he and a couple of hundred fellow squatters even established the "state" of Frestonia in Notting Hill and, in a move many “Scouse not English” types will sympathise with, declared independence from the United Kingdom. Oddly, the same Geoffrey Howe who advised Thatcher’s strategic abandonment of Liverpool supported Frestonia’s independence, becoming their UK ambassador: perhaps he was particularly wedded to the idea of Westminster abdicating its responsibilities wherever possible.

Unfortunately, in 2012 – and in flagrant disregard for the tradition of English Common Law – the authoritarian Coalition Government criminalised the practice of squatting for good. Likewise, in Berlin, officials have repeatedly cracked down on occupiers, most dramatically in 2020 when 1,500 police descended on the self-described “anarcha-queer-feminist” residents of Kreutzberg’s Liebigstraße 34. One is reminded of the fate of the Love Activists who occupied the former Bank of England building on Castle Street, hoping to “provide food, shelter, clothing, love and support to homeless people of Merseyside” until being unceremoniously evicted, prosecuted, and jailed in 2015.

What about a rent cap? While the national Mietpreisbremse – rent control brake – is still in place across Germany, Berlin’s Mietendeckel – the rent cap – was declared unconstitutional in 2021, and it even became possible for landlords to recoup lost back earnings from tenants. How both these facts can be true is a matter for German legal scholars. Whatever country you’re in, the system will always side against the precariat.

In 2015, Liverpool City Council introduced its “Homes for a Pound” scheme. This offered prospective developers a rundown house for £1, so long as they agreed to use their own money to refurbish it and stay there for at least five years. A worthy scheme for bringing derelict properties back into use but, despite the headline-grabbing original outlay, was only an option for people with tens of thousands to spend on renovations. Still, the fact it could be accomplished at all means it’s not impossible to imagine the council undertaking a publicly funded version of Detroit, Michigan’s 2014 nonprofit “Write a House” programme for authors of fiction, non-fiction, screenwriting, or poetry – which ended prematurely exactly because it was crowd-funded – and offer discounted property to artists who otherwise would be subject to the pressures of commercial letting, or even homelessness.

The myriad causes of Merseyside’s cultural stagnation cannot be divorced from national and even worldwide issues. Perhaps this is all the birth-pangs of what Yanis Varoufakis calls technofeudalism, the new global financial model where even capitalists are commercially enslaved to digital landlords. Even in the latter days of what was still recognisably capitalism, digitalisation of music had created a post-scarcity situation for mp3s, and despite the efforts of “copyleft” activists and licencers, we had not yet figured out a way to ensure artists were correctly remunerated when the files that contained their work were no longer merely physical and could be infinitely reproduced. This problem has been further compounded by the rise of technofeudal suzerains like Spotify paying artists around $0.003 per stream — try paying £800 a month with that.

With apologies to Blakean idealism, this is not a happy nor a healthy situation for artists. We like to think there will always be spritely, beautiful, or challenging art because there always has been, but this is the same complacency of the Scouse Exceptionalist – itself ironically a consequent phenomenon of defensiveness and inferiority after decades of metropolitan decline. To accept this narrative is to risk becoming the Scouse Ozymandias, inviting travellers to look upon the decay of a colossal wreck like the oblivious, long-dead tyrant of Shelley’s vision. Cultivating self-expression in Liverpool or anywhere else, is not for mere decoration — like a Superlambanana, or a golden throne outside a Nando’s to commemorate Taylor Swift. There’s only one thing that transcends and survives any city once the budget sheets are dust and the political squabbles have long been forgotten: its art.

Comments

Latest

Get ready: the Aloft trials are coming

Michael Heseltine 'saved' Liverpool. Didn't he?

Cheers to 2025

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

The Decline and Fall (and Rise?) of Mersey Culture

How to kill a city's art scene