The best street art takes us somewhere new. So why does ours always bring us back home?

Armed with a step-ladder and a bottle of white spirit, David Lloyd goes on a tour of Liverpool's public art

The 12th of February, 2019 was a defining moment in the history of street art in Liverpool. For good, or bad? That’s your call. It’s your art, after all. This city is your gallery, right?

That February day saw Camilla Parker Bowles pose for press photographers in front of a pair of outstretched Liver Bird wings daubed onto the walls of the Baltic. For me, the writing was on the wall. And the writing might as well have been live, laugh, love. It was proof that the power, provocation and purpose of street art had finally been whittled down to a photo opportunity for paparazzi desperate to clinch the front page of the Echo.

I doubt the wings’ creator, local muralist Paul Curtis, is losing too much sleep though. His work is popping up all over the city region like a technicolour yawn. If you’ve a gable end, I’d recommend you plant a fast-growing creeper sharpish, lest risk being splashed by the fall out from Curtis and the city’s hardest-working cherry picker every time you leave the house.

And last week saw the announcement of yet another nail in street art’s coffin.

A call went out for artists to bid for a £25,000 commission to create a new piece of art to cover up the substation on Mathew Street. It’s backed by Scottish Power (who own the station), with Liverpool BID and the Beatles Legacy Group. It’s serious money. I’m sure Curtis’ team is already filling out the forms and photocopying their public liability documents.

I’ve always quite liked that substation myself. There’s a kinetic and playful energy to it. It’s like the tipping buckets, but with electricity flowing through its curves instead of water (not that water flows, at all, in the buckets these days).

Scottish Power has got the cash. Its biggest shareholders include the Qatari sovereign wealth fund. Try as I might, I can't imagine John Lennon singing: 'Imagine no possessions, and no Qatari sovereign wealth fund too…’

You may say I’m a dreamer. But, to me, street art — the best street art — rarely blooms from the rubber-stamping from a committee of judges. When energy companies splash the cash on street art, you have to wonder: how did we get here? And should we stage an intervention before the very last drops of joy are wrested from this once-dynamic and life-affirming art form?

Why don’t they just ask for a brilliant new piece of art? No navel gazing, No rules. That would be way more in keeping with Mathew Street’s history.

Curtis, and his rogues’ gallery of Red Rums and Liver Birds, Lennons and Diddy men is content to play the same tune, stuck on repeat. He mines that same need for us to seek comfort in the familiar, without ever attempting to take paint into amazing new places. It’s public, yes. But is it art? Discuss. Left to our own devices, we have a tendency to seek out the comfort of lazy populism around here. Art and culture as a self-referential parade of patronising and lazy tropes. Culture that’s myopic instead of kaleidoscopic. The irony of the Mathew Street commission’s search for an artwork that celebrates the city’s ‘deep-rooted musical and cultural history’ is that, when the Beatles tore up the stage at the Cavern, they weren’t referencing anything even remotely local — they were taking jazz and blues, skiffle and folk from around the globe and creating something fresh, something essential. And they did it, over and over again, with every new album.

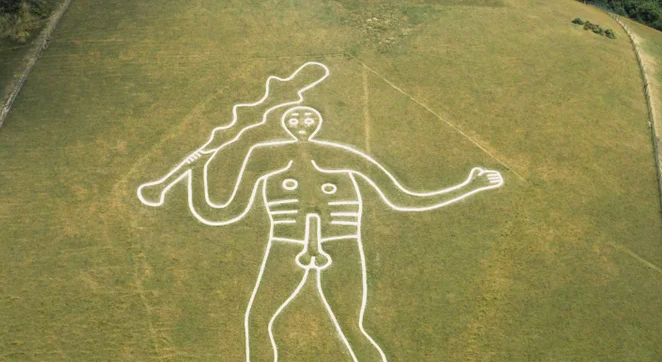

Some say street art started with the spray-can artists of the 60s and 70s, tagging their names across the urban landscapes of New York City, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia. But I’d say, over here, it goes back way further. Two millennia further. What are the freestyle graffiti-esque curves of the Uffington White Horse, or the big-willied chutzpah of the Cerne Abbas Giant if not the tags of local artists saying ‘look at us, we’re fucking cool over here.’ In much the same way the electrifying work from Melbourne to Mexico City says today.

The chances of Camilla posing for a selfie in front of the Cerne Abbas Giant’s 11 metre-long knob are roughly the same as her gurning in front of a mural commemorating the Easter Uprisings on Belfast’s Falls Road, or framing a Keith Haring ‘Crack is whack’ print in Clarence House.

Not that all street art has a duty to be politically charged and powerful. The best street art can just be beautiful or technically brilliant. Let’s face it, it’s an act of audacity to paint something so public, so huge and so in your face. So if you’re going to do it, shock us into looking at it, please. Wake us out of our slumbering commute. Make art, not municipal anaglypta. There’s way too much of the latter around these parts. And things are getting worse.

There’s a Paul Curtis mural near me, of a boy and girl Scout warming themselves by the flickering flames of a campfire. It’s a cruelly ironic scene. Curtis’ clumsy rendering of the girl's face makes it look like she’s had extensive plastic surgery after falling asleep on an induction hob. I am allowed to say this, because this art is in my face. Every day.

As I write, there’s another huge Curtis — of athlete Katarina Johnson Thompson — appearing along Dale Street. It’s an exercise in diligent draughtsmanship, not art. This is a huge, central site. Imagine what it could have looked like if it was given to more capable hands.

For Rob Jones of Liverpool street art curators Plusgraphic, the gold rush is threatening to dilute the art form he fell in love with twenty years ago.

“Like most street art fanboys I was given the bible for Christmas, Subway Art by Martha Cooper,” Rob says of the seminal book capturing the nascent work of the New York graffiti scene’s artists.

After time spent in London getting to know, and working with, some of the UK’s emerging talent, Rob returned to New Brighton where he helped curate the town’s excellent street art trail.

Kickstarted by New Brighton-based entrepreneur and regeneration catalyst, Dan Davies, the town’s alfresco gallery has attracted the attention of big name contemporary art fairs such as Monika in London, as well as sponsorship from the world’s leading spray paint brand, and graffiti-artists’ go-to, Molotow.

“There were localised murals of the Beatles and trams, but we wanted to attract big names from the street art scene,” Rob says.

They came. Within a few years, the town’s streets were basking in world-class works from the likes of Mr Penfold, Ben Eine, Dotmasters and Adele Renault. Victoria Road’s Oakland gallery was hosting screen printing workshops, staging exhibitions and supporting its artists through print sales and the word-of-mouth buzz that happens when something’s done for the right reasons. Wirral Council supported it to the tune of zero pence; despite them happily using images of the trail on its tourist publicity.

Vibrant, fun and technically stunning, the murals on the gable ends of the little avenues that fan out from Victoria Street are a match for any Chicago car park or Berlin wall. Take a look at the alchemic can control of Dublin’s Aches on his piece painted in honour of Guide Dogs for the Blind, which was founded in New Brighton almost a century ago, and you’re seeing street art at its most head spinning. Or the 3D optical tomfoolery of Fanakapan’s helium balloons, which look as if they’re about to lift off the wall before your eyes.

“If you’ve got councils throwing twenty grand at a mural, the worry is you get the equivalent of a pair of wings,” Rob says. “Money doesn’t necessarily push boundaries. It doesn’t make artists want to try new things. It encourages artists who are better at form filling than creative thinking.”

For Rob, the changing dynamic of the street art scene has forced him to take a step back. “It’s lost its way,” he says. “When you see Taylor Swift murals being painted to order in Liverpool it’s a long way from the heart and soul of the community that I fell in love with. For some, it’s become a bit of an industry.”

Not that making money, in itself, is a bad thing. As Rob says, great street artists can earn a decent living by running print releases, or staging shows. It’s when the commission itself becomes the cash cow that the nature of the artform changes.

“I’d never give a brief to an artist, ” Rob says. “You have to trust them to pull out, and have faith in their instincts.” Street art, as Rob explains, is a way for artists to express themselves unrestricted by the traditional demands of a gallery.

In Liverpool BID’s defence, that’s exactly what happened when Rob commissioned French artist Nerone to create a beautifully sinuous, organic slice of street art in the Baltic district, a few blocks — but a world away — from those Instagram-me-please wings.

“BID were great,” Rob says. “I told them what we wanted to create, and they said yes, do it.”

Look at cities praised for their street art and a pattern emerges out of the chaos of colour and pattern. From Bogotá to Lisbon, many have decriminalised graffiti and have fostered a thriving, eclectic street art scene as a result. The more artists, the more everyone ups their game. Although introducing a bye-law banning Sine Missione is worth mulling over, at least.

Liverpool has, as yet, no public art strategy at all, although I’m told one is ‘being discussed’. I’d suggest they get a shufty on. It’s into this vacuum that Curtis, and his ever-expanding business portfolio, is flourishing. Where a multiplicity of styles and artistic incursions should be igniting our urban spaces, we’re being served up a diet of inert, lifeless simulacrums: our walls are like a 2D version of some crap waxworks museum. Oh, look, there’s Ken Dodd. Oh no, wait, is it supposed to be Emlyn Hughes?

Other cities, like Buenos Aires and Athens have embraced street art as a form of cultural expression and political resistance. I might be taking the wrong routes though the city, but I don’t see much evidence of that here. There are pockets, and outcrops of brilliance from local artists such as Betarok75 and Liam Bononi, the Baltic Skatepark, and Zap Graffiti’s excellent graffiti workshops — but for all its increasing ubiquity, street art’s commoditization has neutered its ability to shock, provoke and challenge.

With every big bucks commission its counter-cultural edge is being co-opted by local businesses and councils desperate for a bit of spray-on cool. “Let’s make Crosby the new Cape Town! Slap a huge mural of local girl Anne Robinson, winking, on the side of the library.”

Patronage and lucrative commissions may well be fine in the short term. They help paper over the cracks in this city — and let’s face it, there’s plenty to cover — and a few artists may do very well from it. We’ve got the blank walls. But for street art to really thrive in this city, there’s no guarantee that another blank cheque is the answer.

Comments

Latest

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

I’m calling a truce. It’s time to stop the flouncing

The carnival queens of Toxteth

The watcher of Hilbre Island

The best street art takes us somewhere new. So why does ours always bring us back home?

Armed with a step-ladder and a bottle of white spirit, David Lloyd goes on a tour of Liverpool's public art