Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

World peace, Russell Brand-approved meditation and endless roundabouts

You don’t have to go far north of Skelmersdale town centre to transcend to higher planes of thought. Just a few minutes in a taxi. Nestled amongst some foliage and residential housing, the Maharishi Golden Dome emerges in front of me. The transition between the two is jarring. Skelmersdale is a concrete jungle, all hard edges and postwar modernism. But here at its northern tip sits a strange not-quite-golden saucer. It takes its name from the once globally renowned Indian yoga guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the man who popularised transcendental meditation. And his legacy can be found in Skem.

Skelmersdale, or Skem, is often depicted as Merseyside’s disembodied limb. Its fame, if you want to call it that, is of a dubious nature: it’s characterised by an abundance of roundabouts, dearth of trains and for aspiring to but not reaching utopia. As those features suggest, it’s one of the 60s New Towns populated by those turfed up out of Liverpool by slum clearances.

It’s a town that doesn’t get much positive press, where misfortune seems baked in. The local lore is a smorgasbord of strange tales, like the time the planning authorities are said to have built a sandpit in the town centre, failing to realise that dogs would play in it, thus costing Skem the highest incidence of enteritis in Europe. See also: the time when, during the town’s construction, mad professor Nathaniel Butler — the lead scientist for a controversial programme called Mind Reader — supposedly built an Aspiration Dispersal Field generator in a disused mine shaft underneath the town. Using a network of stone monoliths as conductors, “Skelmersdale was then drenched in a sort of magnetic field which took away all aspiration from the inhabitants”, according to one online explanation.

And while it's hard to believe anywhere could be so lacking in aspiration that giant magnets are the only feasible explanation, Skem is very much the kind of place that gets described as a “forgotten town” to an annual deadline in the Reach PLC titles. A typical headline: “The forgotten town held to ransom by teen 'gangs' where mums fear to let their kids out at night.” Here we learn of a hellish place fraught with violence where residents make comparisons to “Beirut”.

Stereotypes aside, I’m here from an altogether different reason. In 1980, a community of transcendental meditation practioners showed up. David Hughes, one of the original members, greets me at the dome. He’s aware that the language and iconography, domes and yogis, might add up to a certain sort of impression. He’s keen to set the record straight. “Think of it as a kind of health club,” he says. “Like Bannatyne’s. There’s not one set lifestyle that goes with this, you don’t have to buy into a set of beliefs.”

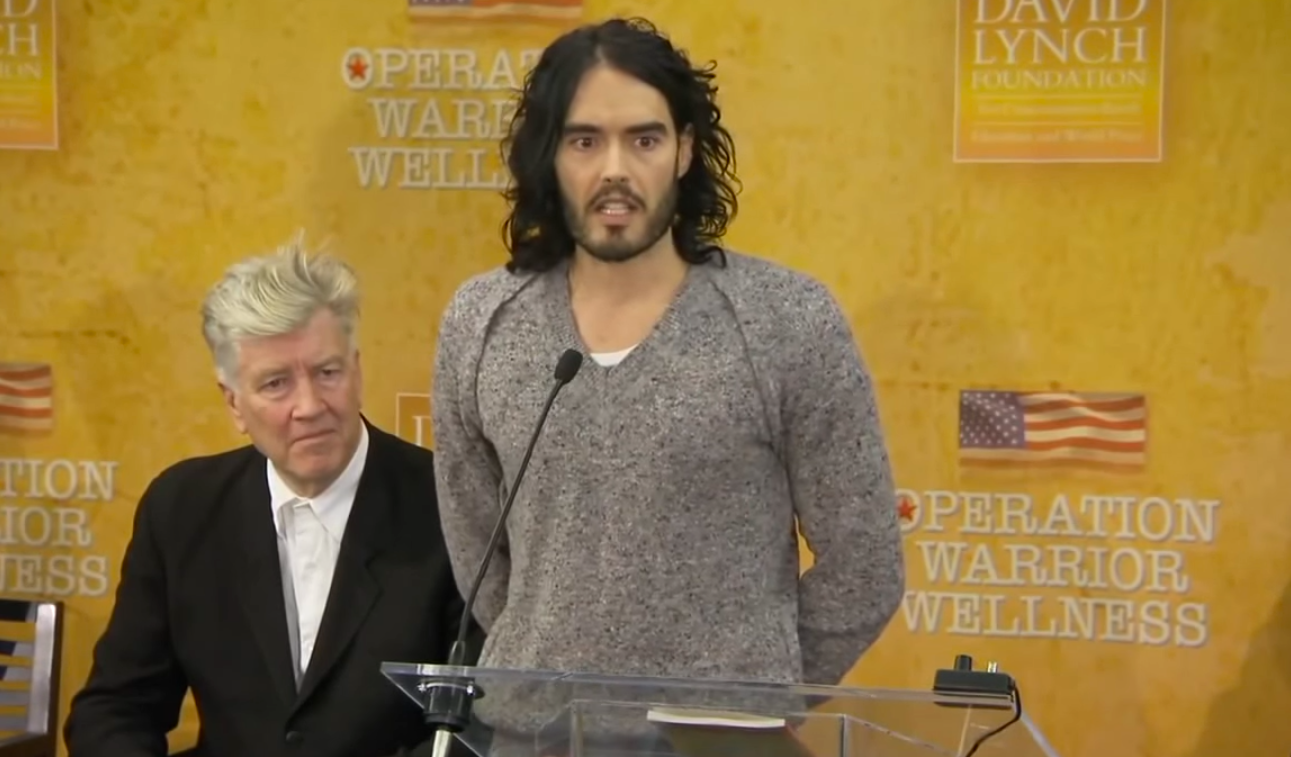

While actual domes are a rarity in the west, TM is not. Many celebrities — like Russell Brand or Paul McCartney — are known to practise. The basic idea involves the repetition of a mantra, while sitting quietly with closed eyes, to lull the body into a deeper state within. The body goes into a deep rest as the mind takes hold of it, with long term benefits like reduced stress. I had been hoping that David might pass on the fruits of his wisdom to me; that by the end of the day, I might be a gold star TM-er. Unfortunately, he tells me that generally, beginners need a few sessions to fully grasp the process — the first one is largely prep and finding a suitable mantra.

Accepting this obstacle with TM-inspired serenity, I push on. My first, most pressing, question, is what led them here. Hughes explains that there is a belief that when the square root of 1% of any population practices TM, the entire community sees an uptick in positive social outcomes: low crime, low anti-social behaviour and so on.

He tells me you don’t have to buy into this to practise, but the basic principle, taught by Maharishi, was that all humans share an underlying consciousness, known as the “field of consciousness”. In the 70s, beliefs grew among some quantum physicists that there was an underlying shared basis of all matter in the universe, and in the view of some TM practitioners our underlying consciousness is our connection to that strata of being.

If consciousness is shared, then it followed that a small number of people doing TM together could positively influence the rest of the population; a soothing thought for the rest of us. Having trialled this concept in Syria and Iran during the 70s, Hughes and a number of others decided they wanted to put it to the test properly, by moving a large number of people into one area and meditating together every day.

The obvious question is: why Skem? The answer here is a touch more practical. At that point they were hoping to create a community of 800 (the square root of 1% of the UK population), but finding enough housing in one place, mid-recession, was tricky. Skem had an estate of houses that had been built and the local authorities were hoping to attract new businesses. As the TM group included a lot of businesspeople, they struck a deal. In the end 120 moved, lower than expected. Many southern practitioners weren’t exactly sold on Skem, Hughes explains.

The Golden Dome, with its now faded yellow roof, came in 1988. In the main meditation hall cushions and pillows are laid out, with the male and female sides separated. Maharishi’s bearded likeness is at the front, as the man who took the Eastern concept of meditation — once the sole reserve of monks in the mountains of the Himalayas — and made it a part of western life.

There’s an innate comedy to the phrase Skelmersdale Transcendental Meditation Community to an outsider. It’s got sitcom potential. It’s like the Solihull League of Scientologists. Or the Milton Keynes Anarcho-Primitivist Commune. It’s probably funny because of the contrast of a place routinely dubbed “the forgotten town…” having once been selected by the followers of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi — the man who evoked a latent spiritually in the Beatles (George Harrison described the trip to his Rishikesh ashram as being like “spiritual Butlins”) — as the petri dish for a British consciousness expansion experiment.

The reality, though, is that such impressions are deceptive. This is a far more relaxed place that the title may suggest; most dome members don’t even regularly come in, preferring to practise at home in their own time. The experiment was secondary in a sense, mostly they practised TM for their own benefits. “In some ways Skem is fortunate in having such a nice facility, but on the other side it can make people wary. Maybe they look at it and think it’s a cult,” says Hughes.

Either way, the results it had on the community were impressive. A new school was established, the Maharishi School of the Age of Enlightenment. In an area with otherwise poor education outcomes, it bucked trends. An Independent article from 1998 reported that the school, with classrooms adorned by the face of its eponymous yogi, won 30 literary competitions and many national poetry contests in a four year stretch, with GCSE results at the top of the county league table.

Back then it was fee paying, now it’s a free school, but attainment remains very high. Educators from all over the world have visited with a view to incorporating TM into their own schooling and a £2 million EU funded study on TM in education came about because they were impressed with the Maharishi facility.

It was even suggested that crime rates plummeted in nearby areas as a result of the group. Yes, an attempt from Maharishi to overturn the British government by beaming thoughts of peace and love into the minds of the electorate failed to succeed in the 90s, but the community locally has seen far greater success.

18 years ago, it all changed. In 2005, with the Iraq war in full swing, the 95-year-old Yogi called the UK a “scorpion nation" and decided that his well-meaning meditative teachings, his “beautiful nectar,” were, unfortunately, serving to “feed the destroyer of the world”. He issued a memo: "We are rejecting one nation — Britain — which has proven to be a poisonous, divisive influence in the world family.” Teaching was to cease. Was Skem losing its meditators?

Nearly two decades have passed though and the dome still stands. Any concerns about a mass exodus never came to pass. “It was an interesting time,” Hughes laughs. He explains that Maharishi was always focused on peace. He believed that “the intelligent way of dealing with conflict would be to reduce the stress in consciousness.” Hughes continues: “He was no fool of course, he was aware the allied army in the Middle East weren’t actually going to sit down and meditate”.

In fairness to the yogi, several armies have since looked into the practice, even if just to improve the mental resilience and mind/body co-ordination of their soldiers. TM is also supposed to be a very effective technique for dealing with PTSD, and in his role as a teacher Hughes has worked with a number of traumatised people. Moreover, a trial in American teaching TM to frontline healthcare workers found a reduction in anxiety of 45% in a two-week period.

Hughes first got involved in 1970 after learning TM at university. It’s seen in many ways as a very 60s concept, or at least a 60s spin on ancient Eastern philosophies, but the 70s were the peak. He thinks Liverpool is maybe more inclined to spiritual practices than other comparable cities; the lingering influence of the Beatles, perhaps. Maybe that goes some way to explaining the whole Cosmic Scouser trend too, though where that’s a little more crystal necklaces and weed, TM is a practice that’s been recognised by scientific studies to have possible health effects ranging from stress relief to reduced blood pressure.

Intrigued by the influence of all of this on the broader town, I head to the Concourse — Skem’s massive shopping centre — but fail to find any TM practitioners roaming free. After twice attempting to talk to people who look at me like I’m speaking in tongues when the words “Transcendental Meditation” leave my lips, a shopkeeper called Tony tells me his nephew attended the Maharishi school, after his brother got involved in the practice. “They’d have to do yoga in the mornings as I recall,” he says, as I picture a hundred teenages sitting cross-legged in a gymnasium achieving higher thought. “I’m all for it,” he goes on. “It’s not really for me personally but they’ve done good for this community.”

Tony’s picture of his nephew’s schooling days is far rosier than his picture of Skem. He talks in the language of those headlines, not quite uttering the words “Beirut” or “forgotten town”, but not far from it either. “One of the biggest problems is the number of kids carrying knives, thinking it makes them tough,” he says. “When you’ve got all these knives on the streets that’s when you get trouble.”

Tony goes on to qualify his comments with talk of closed youth clubs and “nothing for the kids to do,” the same things you’ll hear about every “forgotten town” in Liverpool or the country. Four of Skelmersdale’s seven wards rank in the top 5% of deprived places in the country, according to the council.

The reputation New Towns have more broadly is one of drift, disconnection, soullessness. All feelings familiar to retiree Sue Castles. Her family were early settlers, so to speak, though she was very young at the time. Her mother died 12 years ago, but Sue describes how reluctant she’d been to leave the tenements of north Liverpool. The issue with New Towns was always the impotence of those ushered in. There’s a kind of refugee-ism to it. Of being hauled up out of a familiar environment, even one with significant issues, and told to set up in a new one of unfamiliar faces. Her mother was probably always embittered by that, she says, but Sue hasn’t the same attachment to before. “It’s been a great place to live for us,” she says. “You get a bit of trouble here and there, but it’s far worse in Liverpool”.

Hughes has a more positive take, too. As we walk around the Concourse, he points out the new cinema and talks about the mooted swimming pool and health centre, both signs of positive change. “At first there may have been a dislocation but there’s a tremendous amount of good stuff and the people hang together,” he says. “There’s always gonna be some anti-social behaviour but the friendliness here can overcome a lot of obstacles.”

If the intention of the TM community was to rid Skelmersdale, or indeed Britain, of its ills, then by that metric it’s probably no surprise they fell short. But those who believe that was their primary aim when they arrived in 1980 make a crucial error, Hughes says. “People sometimes say this group got together to bring about world peace. But we didn’t, we did it primarily for the personal benefits to our own lives. World peace would be a nice side effect!”

Comments

Latest

The carnival queens of Toxteth

The watcher of Hilbre Island

A blow for the Eldonians: ‘They rubber-stamped the very system they said was broken’

How Liverpool invented Christmas

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

World peace, Russell Brand-approved meditation and endless roundabouts