Rising sea levels: where in Merseyside stands to lose most?

Cracks in Antarctic glaciers spell trouble

At school, I was taught the theory of sea level rise. You might have learned it, too: the earth warms, ice caps melt, the volume of water increases, coastlines recede. Even though these lessons were taking place in Norfolk, one of England’s counties with the most to lose from this process, it all felt incredibly abstract and remote. I filed it in the same mental category as the eventual death of the sun: useful to understand for exams, but not a threat I’d encounter in my lifetime.

But what if I was wrong? What if the seas start reclaiming the land rather sooner than many of us had anticipated? That’s a question which I imagine preoccupies many Brits, for obvious reasons. But for those of us in Merseyside, home of horrifying articles about towns and areas set to plunge underwater by — well, each one says something different — it’s less a question, and more of a storm cloud skulking above.

Certainly the Environment Agency (EA) is taking the threat seriously. In 2019, then Chair Emma Howard-Boyd even warned that certain UK towns might have to be abandoned as the waters rise, when launching a draft flood management strategy. They dialled back some of that rhetoric in the final draft, but it’s clear that many are spooked. They’re not the only nervous ones – around three quarters of British adults experience some anxiety about the climate.

If that’s your natural tendency, this article may not help. But I’ll be trying to establish some facts about what can be quite an emotive subject. I should cover myself first though: understanding, let alone predicting, future sea-level rise is insanely complicated. The earth is not like a bathtub. The amount of sea-level rise in any one place is affected by weather systems, currents, and underlying geology. The sea is always going up and down with the tides, and the situations to worry most about are those playing out against a perfect storm of conditions: high-tide, and gale-force winds that drive the water towards the land. Things are further complicated by the role of sea defences – more on that shortly.

Wirral on the frontline

So how bad could the flooding get? The EA carried out some modelling in 2019 that looked at three different scenarios, depending on the emissions path the earth ends up going down. Handily, they provide estimates for Hilbre Island, just off the coast of the Wirral. They compare how high the water would rise in the kind of flooding event that might happen typically once a year, as well as those that might happen once every 200 years, or even 10,000 years. By 2100, an annual flood event might cause 5.83m of sea-level rise – but if it’s a really bad year, and a one in 10,000 year type flood hits, the water could rise as much as 7.08m. That’s about as tall as two and a half ambulances on top of each other.

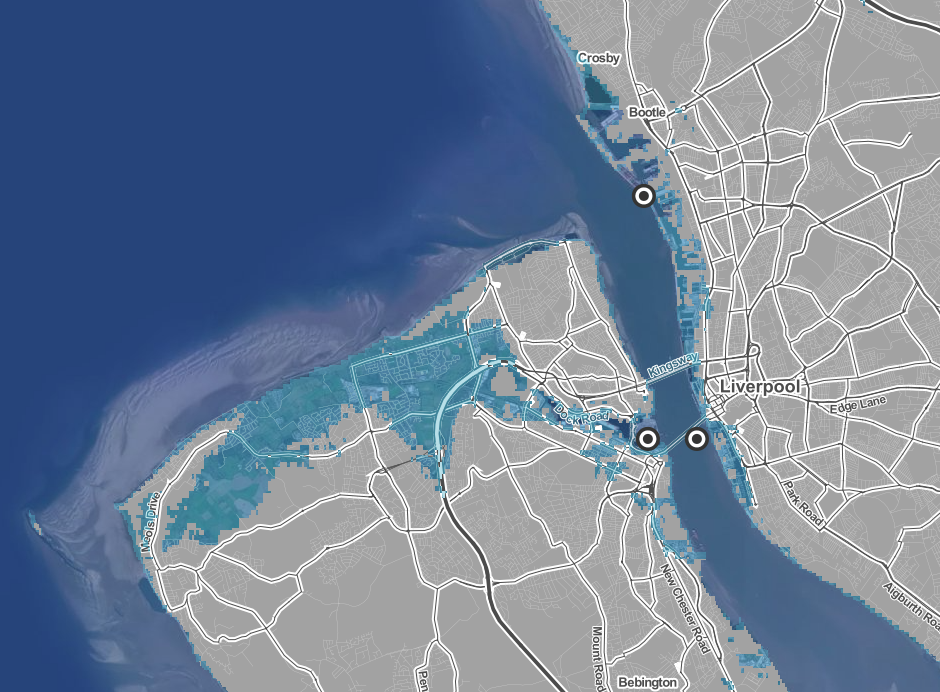

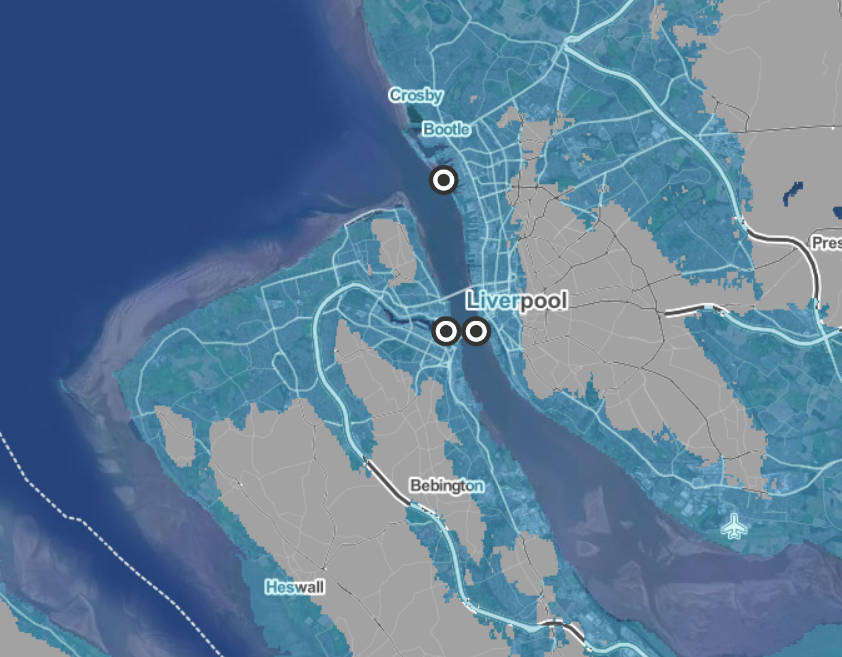

The Surging Seas website by Climate Central shows simplistic modelling of what these types of flood events might mean for Merseyside. At five metres, the docks in Liverpool would be mostly overwhelmed. The rest of the city, though, would remain largely out of reach of the rising tides.

But the real damage would be felt on the Wirral. Across the peninsula, most of the land is low-lying. Absent sea defences, and much of Leasowe (including the Typhoo tea factory) would be underwater in one of these events, and Wallasey would be cut off from the mainland. Things could also get pretty wet in parts of Birkenhead, and some of the major roads, such as the A41, would be cut off.

It’s hard to know exactly what that would mean in terms of the number of properties affected, but already the EA estimates that 510 properties in the area are at risk from tidal flooding – a figure that will only go up with sea level rise.

Sea walls: solution, or sticking plaster?

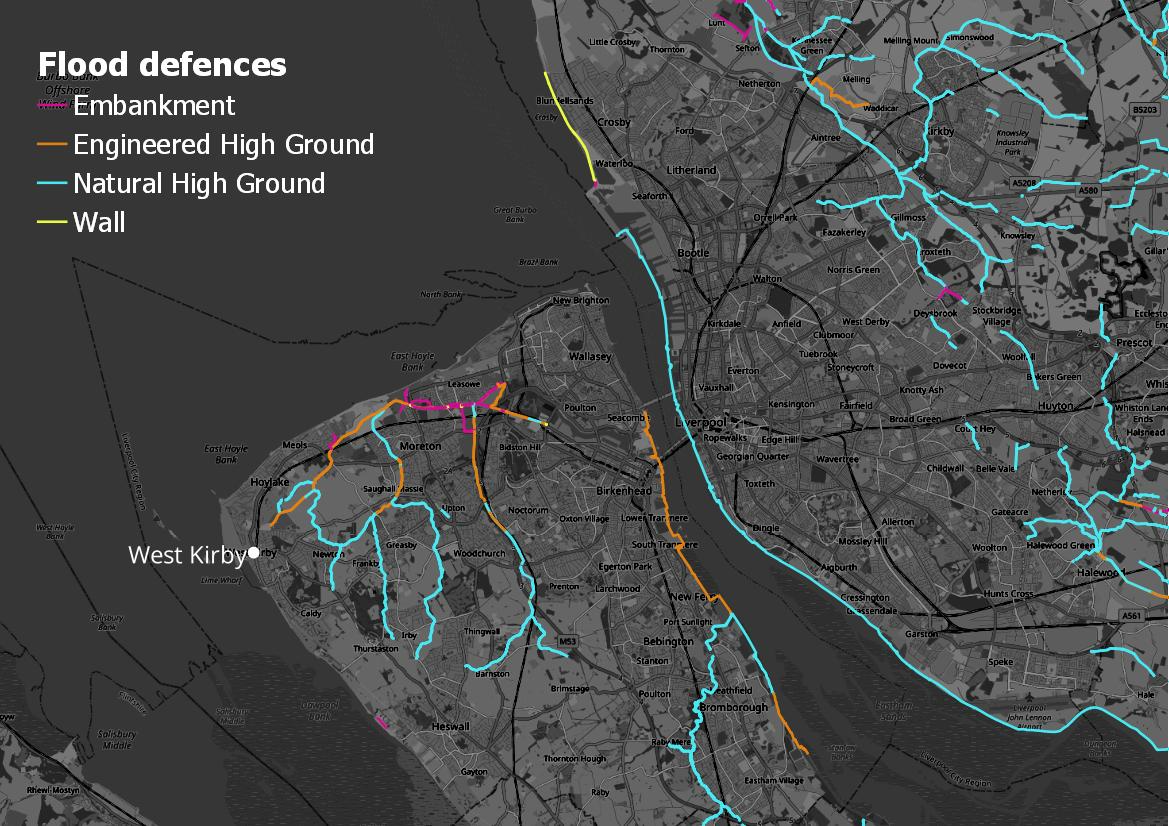

Before we get accused of scaremongering, there’s one crucial caveat: this modelling doesn’t include sea defences. So how much protection is there? The EA’s dataset of where the defences are found shows that a lot of Merseyside has some protection. But look closer, and most of it is “natural high ground” – i.e. the way the land is shaped already gives a fair degree of protection. In some areas (orange on the map) that’s been beefed up, with some engineering. And only in one place, Crosby, is there actually a sea wall in place.

That is, until now, where a new sea wall has just opened in West Kirby (not currently shown in the dataset). In this town, flood risk isn’t just some theoretical possibility – a major storm surge battered the town in 2013, which was enough to carry off a car or two. It’s just opened, but has been overshadowed by some controversy around the scheme – it’s gone over budget, and taken almost a year, during which time the seafront has been marred by building works.

I head down to the town to see what people think of the new protection and how concerned they are about rising sea levels. It’s a beautiful day, and many people are soaking up the sun on the beach, so I feel a bit bad about interrupting to discuss climate doom. Thankfully, most are happy to talk.

On balance, the reaction to the new wall is positive, though by no means universally so (and those who are opposed are really opposed – “they’ve destroyed a beautiful location”, one tells me). Even the detractors tend to agree that it looks fairly nice – the council have used a wave like pattern with benches all along, while the sandstone colouring blends in well with the surroundings. “It’s absolutely wonderful”, pensioner Chris Brett tells me, who used to work in construction, and thinks they’ve done a good job. He’s looking out to where his wife Brenda’s ashes were scattered four years ago, and though this place is clearly very special to him, he welcomes the changes.

I encounter two main objections. The first? Money: the budget has risen to almost £16m, after issues around ground conditions, a redesign, and increasing costs of materials. Not all of that has come from council coffers – the EA has also put in – but some clearly felt the money could have been spent on what they saw as more pressing priorities. Many were fairly sceptical of one claim made to justify the scheme – that 26 people could die in its absence. You have to price human lives pretty highly in any cost-benefit analysis, so no doubt the use of this figure helped to get the business case agreed.

The other main complaint may not seem world-shattering, exactly, but I am obliged to report it, since no less than three people mentioned it. Apparently, the wall blocks the view of the sea if you’re sitting in a car on the road. The “old dears” who come here to eat their fish and chips in the car while watching the sea can’t do so any more. But the council has provided lots of benches along the wall! I protest. But I’m told that in winter this isn’t an option, which is fair (is anywhere colder than a wintertime beach? I mean, yes, but it certainly feels bitingly, stingingly chilly in January on the average British beach). I ask one woman, Pat, who calls the wall a “travesty” and is in fact sitting in a car, whether she can see the sea. It turns out she can – but then, as her husband Malcolm points out, she is in a 4x4.

Are people anxious about rising sea levels? Again, it’s a varied picture. “You know what, it doesn’t cross my mind”, offers one woman, while two friends Talitha and Jennifer are much more concerned. Talitha lives in a flood risk zone, and worries that flood defences only work as a medium-term measure. “It’s remedial action”, Talitha tells me, looking at the sea wall. “It’s a lot easier to do this than to implement big and real change.”

Then, of course, there’s the impact of all this on house prices. I speak to one woman living just back from the front who has just put her house on the market, and is concerned that hostility to the new wall will bring down the value she gets. “Don’t you dare write a negative article about it”, she warns me, half-joking, while refusing to give me her name. I tend to think an attractive sea wall – and the protection it provides – will probably increase house prices, but that remains to be seen.

Where the real action is: Antarctica

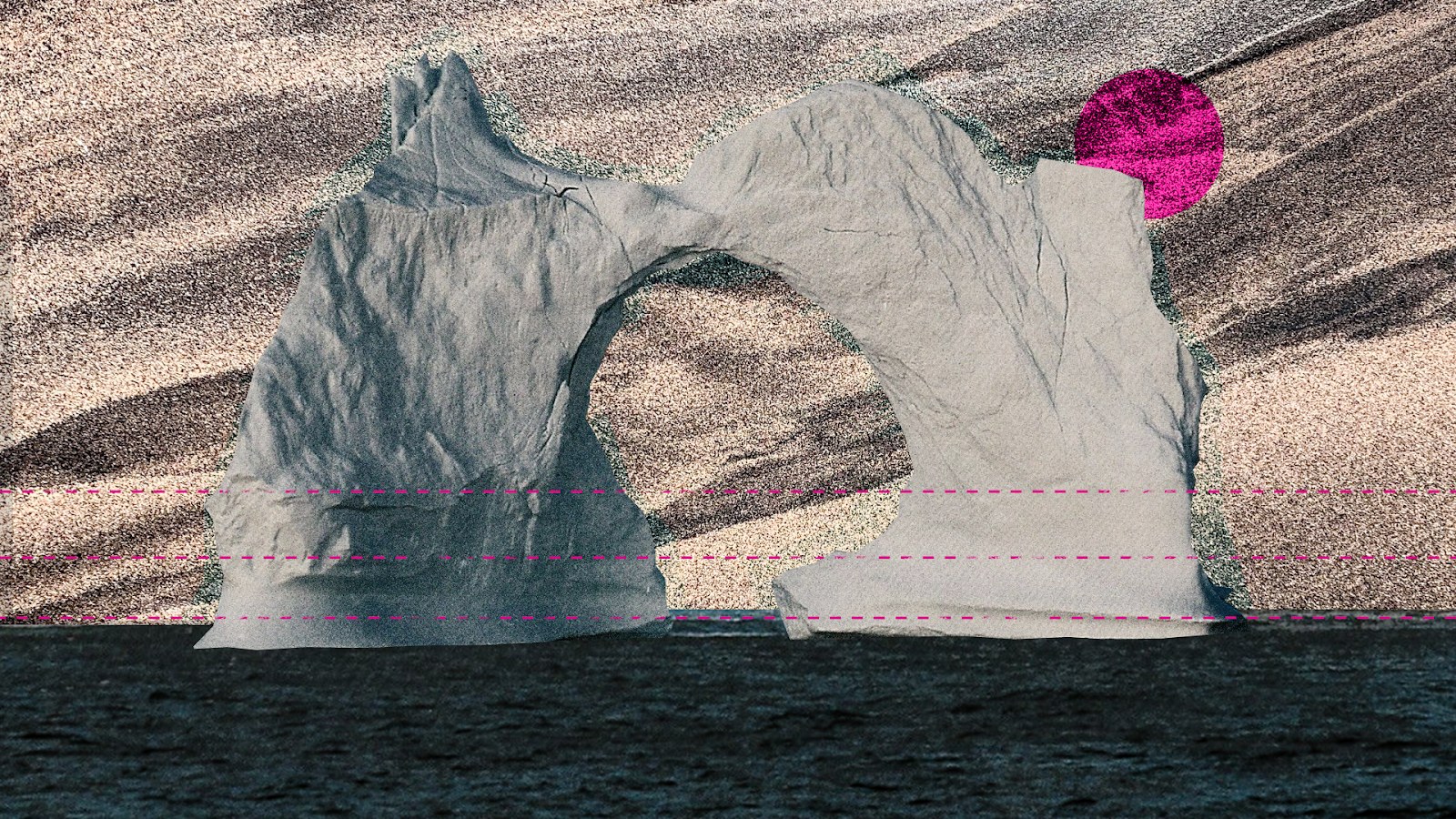

It would be nice to think we have the ability to manage this threat with a combination of sea walls and barriers, at least for the next couple of centuries. But there’s one almighty caveat in the EA’s modelling. “There is a large degree of unquantified uncertainty with these projections”, they write, “associated mostly with the potential for accelerated ice loss from the West Antarctic ice sheet”. The fate of some of Merseyside's coastal communities may depend on events happening over 8,000 miles away.

The Post budget didn’t allow for a trip to one of Antartica’s research stations but the read-out from scientists working there is concerning. That’s because, when it comes to melting ice caps, it’s not simply a gradual process that might happen slightly faster or slower depending on the amount of global warming.

The key question is what happens to the Thwaites Glacier, which is also known as the “Doomsday Glacier”. That’s because not only would its melting trigger a lot of sea-level rise, but it holds back other glaciers, which could also slip into the ocean at this point. As Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at Colorado University, has put it: “If Thwaites were to collapse, it would drag most of West Antarctica’s ice with it.” Recent surveys of the glacier have shown that large “staircase” cracks are forming, where melting is happening much more quickly than on the bottom. There’s also evidence that the glacier is losing its hold on the underwater mountain that holds it in place. If melting carries on at the current pace, it would be dislodged within a decade, leading many to predict Thwaites will break up altogether. While the sea level rise impact could take a long time to work through, it would be essentially “baked in” at this stage.

And there’s bad news from the other side of the continent, where the East Antarctic Ice Sheet – generally believed to be much more stable – is showing signs of strain. This contains four-fifths of the world’s sea ice, and were it to melt altogether, there would be enough water to raise global sea levels 52 metres. No-one is predicting that in the immediate future, but last year most of the Conger Ice Shelf in East Antarctica collapsed after record temperatures, with experts warning it could be a taste of things to come.

Surging Seas only shows a maximum of 30 metres rise, but it’s a grim picture. When you increase water levels to that sort of extreme, most of the city centre would be inundated. Water would be lapping at the tracks in Lime Street Station. Wallasey becomes Wallasey Island (replacing Wallasea Island in Essex, which by now would be completely underwater). And the low-lying areas to the north – including Bootle and Crosby – would be totally submerged. The airport, and almost all of the Merseyrail network would also be lost to the waves.

It must be stressed that few climate scientists would confidently predict that we will see these levels in the near future, if ever. But most wouldn’t rule them out, at some stage, either. And the concerning thing is that even if we do effectively tackle carbon emissions, a lot of these effects may already be baked in.

A global issue

Of course climate change is bigger than Liverpool, but the example of this city has global relevance. Liverpool’s growth in the industrial period was driven by its location – facing Ireland and the United States it was a natural location for a port, and all the trade that brought. The pattern is replicated worldwide – about 40% of the global population lives within 100km of a coastline, and around 10% live in coastal areas that are ten metres or less above sea level. Most of the world’s mega conurbations – such as New York City and Shanghai – face onto the sea. A significant rise in sea level would cause a major human and economic catastrophe, with potentially millions of displaced people looking for somewhere to go.

We don’t know if, or when, that will happen. Massive uncertainty surrounds how much sea levels might rise, and when. But those who study Antarctic sea ice are concerned. Melting is already underway, and some of the glaciers that play a vital role in the structure of Antarctica are showing worrying signs of wear.

Most of those I meet at West Kirby – even those who express concern over climate – don’t seem too alarmed. On a sunny day at the seaside the threat remains fairly abstract. For myself, I expect that, in time, the sea wall will come to be seen as a good investment.

But the EA caution that such structures will only get us so far. “Building our way out of managing future climate risks will not always be the right approach, particularly as the changing climate drives more extreme weather patterns”, they conclude. The unspoken implication is that some settlements will have to be abandoned to the rising waters.

Settlements is an abstract, academic word: imagine, instead, a world you once knew vanishing. Houses your friends grew up in, schools you attended, the backdrops to birthday parties and bike rides all submerged underwater. A sea wall can only offer protection up to a point. But the stakes are high — look behind it. This is what we stand to lose.

Comments

Latest

Losing local radio — and my mum

A place in the sun: How do a bankrupt charity boss and his councillor partner afford a “luxury” flat abroad?

Gritty, cheeky, sincere: How Martin Parr captured the spirit of Merseyside

Liverpool’s hospitality scene is changing. So why are we reluctant to shout about it?

Rising sea levels: where in Merseyside stands to lose most?

Cracks in Antarctic glaciers spell trouble