Revengers, assemble!

A campy dystopia set in Liverpool was panned upon release in 2002. Laurence makes the case for rediscovering a classic so forgotten even its screenwriter doesn’t remember it

How's this for a movie night: Necrophilia, incest, murder, political intrigue, garish costumes, and a superb ensemble cast, all set and filmed in Liverpool?

No, we’re not talking about Brookside. This can only be Revengers Tragedy, the 2002 adaptation of the 1606 stage play The Revenger’s Tragedy (author unknown, but it was probably by Thomas Middleton). If you were to both read the play and watch the film, you’d know the plot complications, Jacobean language, and extraordinary violence have been transposed to the screen faithfully.

But why, you might ask, are we in the then-future Liverpool of 2011, where natural disasters have apparently precipitated social collapse and aristocratic fascism?

Why is kindly old national treasure Derek Jacobi wearing a ponytail and nail varnish and snogging human skulls?

And of all the movies set or made in Liverpool, why am I telling you about this one?

Let me tackle the last question first. Liverpool, it’s true, has a solid track record on the silver and small screens, from Business as Usual to Letter to Brezhnev. But much as I admire Boys from the Blackstuff, keep up with everything written by Jimmy McGovern, and hold a candle for The Long Day Closes, the bulk of the city’s filmic exploits have been kitchen-sink social-realism or police procedurals more likely to inspire terror than tourism. Even The 51st State, the sub-Tarantino mess that at least tries to do things with a touch of hyperreal flair, is another bloody crime drama. The sum total of Liverpool’s surreal or visionary cinematic art surely cannot be Yellow Submarine.

Enter Alex Cox. Born in Bebington in 1954, Cox is perhaps best known for two punkish cult hits from the 1980s: the science-fictional black comedy Repo Man and the Sex Pistols biopic Sid and Nancy. It was all downhill from there. Box office flops and a Writers Guild blacklisting precipitated a stint in the film-financing wilderness. Following a “Nicaraguan period” and a “Mexican period”, this Welles of the Wirral returned home in the late 90s.

Revengers Tragedy was part of Cox’s subsequent Liverpool period. “I read the play in 1976 when I was supposed to be studying for my exams as a law student,” he says in an on-set documentary. “It was much more fun than law books! Two scenes in and the main character is carrying his girlfriend’s skull about. I thought, ‘I should be directing this!’”

Tod Davies, the film’s producer and Cox’s wife, was a little more hesitant pre-release. “It’s difficult to say how modern audiences are going to relate to a Jacobean tragedy that’s been updated to Liverpool in 2012 [sic],” she said. “It’s not something you can have a focus group about. It’s never been done before.”

On release, the film received less-than stellar notices from critics. The BBC’s reviewer described “moments that are painfully amateurish”, while the Time Out Film Guide says “one struggles to be impressed” by this cross between a “threadbare [Derek] Jarman and a school play.” According to the BBC, it made back a mere £20,000 of its £510,000 Lottery grant at the box office.

Consequently, I think it’s fair to say Revengers Tragedy is a largely forgotten film. Even its screenwriter, Frank Cottrell-Boyce, told me when I reached out about it: “I barely remember this. It was looong ago.” Andrew Schofield, through his agent, declined to comment.

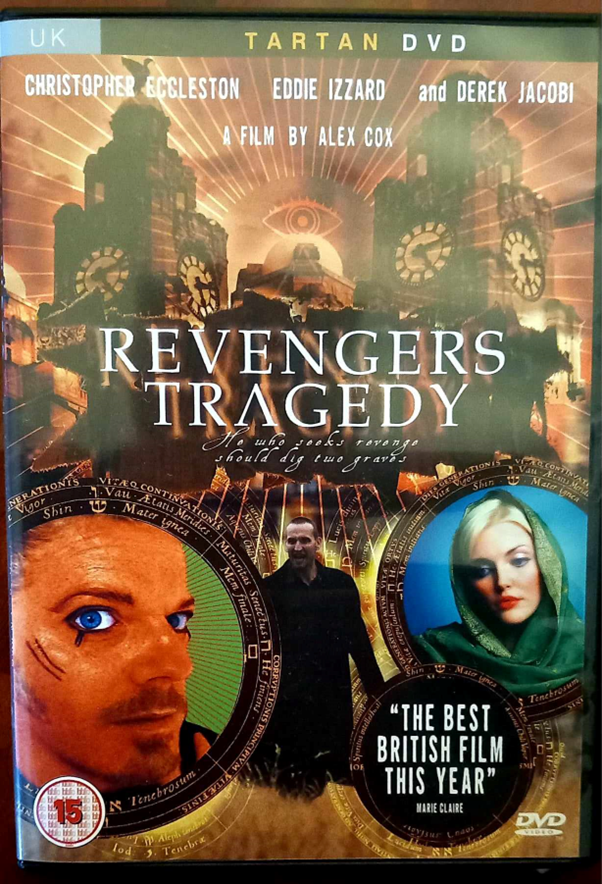

I recently dug out my old DVD from Tartan – a long-since defunct film distribution brand I’ll always associate with quality, since it introduced me to such cinematic excess as Audition, Battle Royale, and Oldboy at an impressionable age. The wide-eyed, self-mutilated, and frankly orange visage of Eddie Izzard, plus Sophie Dahl’s as benign but over-exposed Madonna, stared back at me, heads floating either side of Eccleston. The backdrop is the Liver Building, the twin clock towers arranged by a mentally unbalanced Photoshop enthusiast either side of a flaring, Illuminati-style eyeball atop… is that Bidston Observatory? “THE BEST BRITISH FILM THIS YEAR”, screams the pull quote from Marie Claire. (What — better than Love, Actually or Johnny English!?)

Although I saw them at the same impressionable age, the impact Revengers Tragedy left on me was less profound than, say, Audition, but also less traumatic. I was always just pleased it existed — I have a tendency to exhibit a localist bias, mildly overrating things because of their Merseyside connection. Popping in the DVD and settling in on the couch, I wondered if I’d feel differently about it this time around. Was this one that Tartan got wrong?

The plot itself, as I may have mentioned earlier, is not for the faint-hearted. Vindici — played by Christopher Eccleston at the peak of his sexiness — has been living away from Liverpool since his wife, Gloriana, was murdered. (Like in the original play, he still carries her skull around.) The Duke of Liverpool (Jacobi) poisoned Gloriana because she wouldn’t “consent to his lust” before having sex with her corpse. Revenge on his mind, Vindici comes back, teams up with his brother Carlo (Andrew Schofield) and his sister Castiza (Carla Henry). Vindici disguises himself so he can get close to the Duke’s ambitious son Lussurioso (Eddie Izzard). I say “disguise,” but Vindici just shaves his head a bit — nevertheless, it’s so convincing even his own family don’t recognise him. There’s also a whole subplot about one of the Duke’s other sons raping or attempting to rape Imogen, the daughter of Antonio. Who is Antonio, you ask? I don’t know, but he’s played by Tony Booth. Clear?

This is a film that commands attention, opening with a bus full of dead people crawling with flies. Eccleston, who stalks through scenes like a skinhead panther in a long-coat, steps out onto the backdrop of a piss-yellow digital sky before beating up a gang of nightmare-scallies with tracksuits, facial piercings, and odd symbols scratched into their skin.

Then begins the Chumbawamba soundtrack, which repeatedly reprises either a high-tempo it’s-business-time beat when characters are getting out of limos or striding towards combat, or else a brooding, contemplative, Twin Peaks-esque refrain when they’re doing literally anything else.

Competing rather than harmonising with this aural geography is Cox’s Baz-Lurhman-on-a-budget aesthetic – multicoloured plastic-bead curtains; the rusted hulks of cars; open-shirted weirdos in pink cowboy hats and nipple piercings mincing into vital sex scenes; debased Catholic imagery of ashen foreheads, shadowy crypts and veiled virgins; and the head-wrapped working-class demonstrators turning over cars in scenes redolent of Middle Eastern protests. (The film’s final image was originally meant to be the Twin Towers collapsing, but after desperate appeals by the film’s financers, it instead ends with a common-or-garden nuclear explosion.)

By the time you get to the key scene of Eccleston leading sacrificial lamb Derek Jacobi — looking like a cross between Karl Lagerfield and Count Dracula — through Aintree Racecourse, it’s clear the film possesses a unique (and, it has to be said, chaotic) tone and feel. So much so that the dialogue and convoluted plot of the Jacobean original don’t really matter too much – through the camp costumes and occasionally OTT performances, it’s somehow pretty easy to tell what’s going on. Honestly – it’s all vibes. Just go with it.

And it doesn’t just happen to be set in Liverpool. Watch for long enough and you’ll see local talent besides Henry, Schofield, and Booth, including a young Stephen Graham, a walrus-‘tached Michael Starke, and even Margi Clarke chewing scenery like a one-eyed Scouse barracuda. When Eccleston delivers a key soliloquy, he does so with the Liver Building looming behind him like a sky-high gravestone. The finale makes psychedelic use of Grand Central Hall’s beguiling interior with its variegated Art Nouveau grottos. Furthermore, there’s something very Liverpool about a city betrayed and dominated by forces beyond.

While I take the point of the film’s first reviewers that there’s an amateur and stagey feel to some of the scenes, this is less of a problem if, like me, you grew up on 70s Doctor Who on VHS with its bubble wrap aliens and papier-mâché monsters, microbudget Ken Russell perversions like Salome’s Last Dance, Brechtian theatre where the audience is never meant to believe the events are actually occurring, or anything where the artist’s ambition outstrips their budget. There’s something quite gratifying about meeting a project like Revengers Tragedy on its own terms, augmenting its visions with your own imagination the way you would a play or novel.

What’s harder to overlook is that, while the evil Duke of Liverpool and his deranged brood are done up like rejects from a gay Mardi Gras rave, the film’s heroes (who, in fairness, are also pretty amoral) are decked out in cool black or hi-vis proletarian chic. It would be nice to say the flagrant flamboyance of the villains makes them more fun than the relatively straight-laced protagonists, but Izzard aside, Cox never allows you to enjoy this array of twisted psychopaths the way you would a Hannibal Lecter or Darth Vader. You might chalk up this disparity to some light homophobia, or you might just call the film a pervophobic hallucination, in which tough guy heterosexuality is shorthand for sympathetic.

Revengers Tragedy isn’t a perfect film, even with its perfect cast and perfect costumes. Maybe it’s the movie equivalent of Big in Japan, the Liverpool band whose members would all go on to bigger and better things elsewhere. But the film’s rough edges, flat lighting, and sometimes uneven energy do not, for me, undermine its unique pizzazz and chutzpah. Would a budget big enough to smooth over its infelicities also scour away its psychedelic potency? To quote Alan Moore, money often has an inverse relationship with imagination. In a city chock-full of police dramas and socially conscious miserabilism, aren’t we glad such an audacious and bizarre artefact got made? In a recent essay, Post contributor Jon Egan called Revengers Tragedy Cox and Cottrell Boyce’s “as yet undiscovered masterpiece.” I think it’s time for you all to rediscover it. Revengers, assemble!

Comments

Latest

Get ready: the Aloft trials are coming

Michael Heseltine 'saved' Liverpool. Didn't he?

Cheers to 2025

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

Revengers, assemble!

A campy dystopia set in Liverpool was panned upon release in 2002. Laurence makes the case for rediscovering a classic so forgotten even its screenwriter doesn’t remember it