Remembering my brother through his pictures of Liverpool

'It was only in later years, after the death of our father and then our mother, that we became closer'

Dear readers — we have some great news about The Post today, and a very moving read by the veteran national newspaper journalist Rosie Waterhouse.

In her distinguished career, Rosie has done groundbreaking work for the likes of The Independent and The Sunday Times, most notably her extraordinary investigation into the so-called “satanic panic” in 1990. For us today, she has written a very beautiful ode to her brother and his depiction of Liverpool.

The Post gets lift-off

First our news… As many of you know, we have been in a soft-launch phase since we started this newsletter to provide updates on the Tier 3 lockdown at the end of last year. But now we’ve been given a bit of funding by Substack (the platform we use to publish our emails) to get The Post off the ground properly. That means:

- We have enough funding to hire a full-time writer and editor in Liverpool and pay for some great freelance writers too, and we aim to start publishing twice a week later this summer and then to start publishing on a full schedule in the autumn.

- At that point, we will open up paid memberships for those who would like to subscribe. Post members will receive all our journalism and support the growth of a high-quality alternative source of news on Merseyside — one that prides itself on thoughtful writing, serious reporting and never covering stories in thousands of pop-ups and ads.

If you want to write for us, either as a staffer or a freelance contributor, please email editor@livpost.co.uk ASAP. We would like to hear from journalists from a range of experience levels who want to re-imagine what local news looks like.

Mini-briefing

- Commissioners named: The government has announced the four independent commissioners it is sending to oversee Liverpool’s council. They are led by Mike Cunningham, who grew up in Liverpool and is a former chief constable of Staffordshire Police. “Interventions of this kind are extremely rare and underline the severity of the failings at Liverpool City Council,” a statement says. Read more.

- Captain’s honour: Liverpool captain Jordan Henderson has been awarded an MBE for his services to charity, it was announced last night. The midfielder is an ambassador for the NHS Charities Together group and last year he helped created the ‘Players Together’ initiative that encouraged professional footballers to donate to the NHS. “My family and I feel greatly humbled to be recognised in this way,” he said in a statement. Read more.

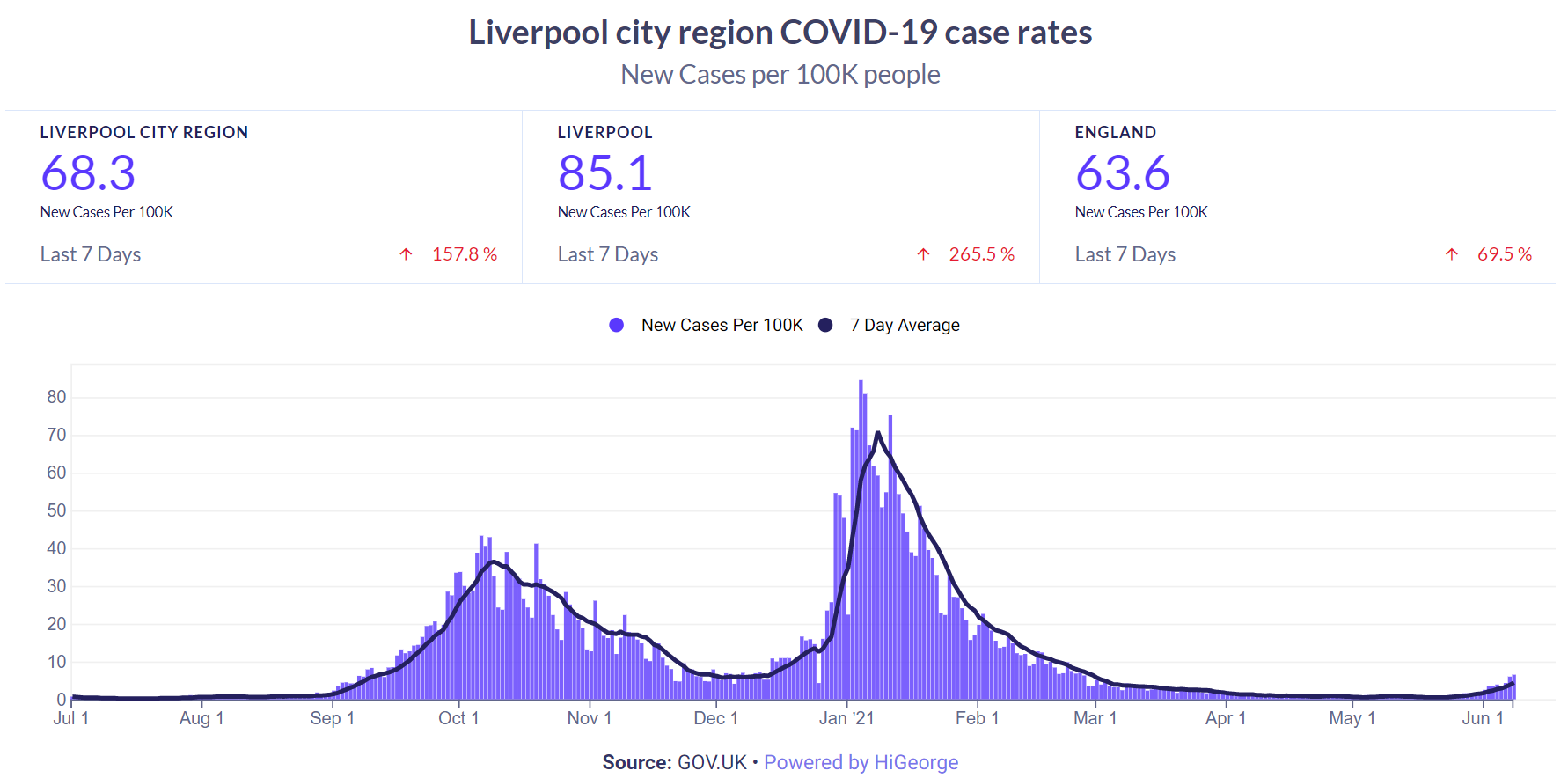

- Covid-19 update: Cases are now rising fast across the city region. Liverpool’s case rate (the number of new cases per week per 100,000 residents) is now 85.1, up 265.5% compared to the previous week. The Liverpool City Region rate is 68.3, up 157.8% in a week. Both are now higher than the case rate for England, which is 63.6, up 69.5%. You can follow The Post’s live dashboard here.

Things to do

- Roots of AI: The World Museum’s exhibition ‘AI: More than Human' looks interesting. It “tells the rapidly developing story of AI, from its extraordinary ancient roots in Japanese Shintoism, to Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage’s early experiments in computing, through to the major developmental leaps from the 1940s to the present day.” More information here.

- Poetry jam: You can catch The Summer Poetry Jam at Liverpool Parish Church this evening, from 7-9pm. “This event celebrates some of the creative performers, wordsmiths and musicians who grace our city and region with their manifold talents,” the organisers say. Book here.

- Seamen story: We really enjoyed this long read in the Guardian about the betrayal of Liverpool’s Chinese seamen. “During the second world war, Chinese merchant seamen helped keep Britain fed, fuelled and safe – and many gave their lives doing so. But from late 1945, hundreds of them who had settled in Liverpool suddenly disappeared. Now their children are piecing together the truth.”

Vauxhall Ladies. Liverpool, 1987.

— British Culture Archive (@britcultarchive) 7:57 AM ∙ Jun 9, 2021

Photo © Rob Bremner.

- Mayor profile: Who is Liverpool’s new city mayor Joanna Anderson? The BBC’s excellent ‘Profile’ programme has made a 15-minute radio piece about Anderson, interviewing her friends and colleagues and filling out some detail about her upbringing on the Netherley Estate. Listen to it on BBC Sounds here.

- Prison drama: ‘Time’, a series by Liverpool screenwriter Jimmy McGovern, starring Sean Bean and Stephen Graham, has received great reviews. It follows a former teacher who has been sentenced to four years inside for drink-driving after an accident that left a cyclist dead. Watch it on iPlayer here.

Remembering my brother through his pictures of Liverpool

By Rosie Waterhouse

During the past year, I’ve been reflecting on early memories of my brother Damien, and how we related to each other growing up. The truth is, in childhood, I don’t think we were very close at all. We were two very private little people, in our own little worlds with our separate groups of friends. Both quite thoughtful but we never confided in each other. Even though we went to the same schools — Roman Catholic, infant, junior and secondary — we didn’t engage. He was two years older.

In my mid-teens, we got to hang out in the same crowd. I liked his friends. We would go to the same pubs, parties, go drinking and dancing, listening to the Rolling Stones and Status Quo. But I never really understood him. I was too preoccupied with my own future, and working out the meaning of life. I left home aged 19, for my first job as a rookie reporter on the Chester Chronicle, and left him to it.

It’s strange how I have so few memories of engaging with Damien as we were growing up. As we grew older, we drifted further apart. While he stayed living at home with our parents, in homes in Brookhouse, near Lancaster and then Kirkby Lonsdale, I moved away, with my journalism jobs firstly in Chester, then the Manchester Evening News, and from 1986 had 30 years in London working on national newspapers.

It was only in later years, after the death of our father and then our mother, that we became closer. And I realised he needed care and support. It was when I had to write a tribute for Damien’s funeral, just over a year ago, that I focused my mind on the sort of man my brother was.

I wrote:

Damien was a very private person. A quiet man. Like one of his heroes John Wayne in the film The Quiet Man. But like Wayne in that film, he could be stubborn, steely and determined. He loved history; he thought of himself as a fisherman, and a Celt - having researched our family history on my mother’s side, [she was an Angus], he reckoned we were descended from Flora MacDonald and he took great pride in declaring himself a clansman and on special occasions could be seen around the town sporting the red and the green of the MacDonald clan colours.

From the many accounts of his friends Damien had some wild times in his youth, usually involving cars. There was also a deep sadness. He never married. In his late twenties he fell in love with a Spanish girl who, it turned out was betrothed to someone else, and I don’t think he ever got over that loss. Damien was passionate, principled, a loyal friend, he was also reckless and great fun. In his later years I spent a lot of time with him. He was a good guy. He never gossiped about anyone. He was a brilliant artist, a tragic character who deserved greater recognition and reward.

Sometimes when we lose people, we find ourselves piecing together bits of their life that seem newly meaningful — patterns that have emerged anew after the kaleidoscope has been shaken. For me thinking about Damien’s life, I have been thinking a lot about his relationship with my father, Jack Waterhouse, and the love of art that he and Damien shared — in particular their passion for the beauty of Liverpool.

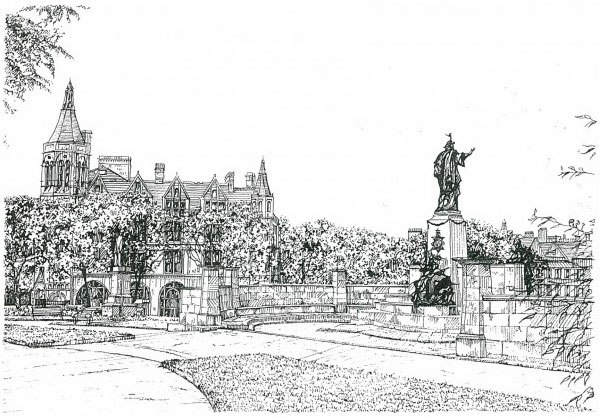

My late father had an enduring love of the architecture of the city. He must have acquired it after he left school and the confines of a strict Catholic home, in the rather austere city of Lancaster, to study Architecture at the University of Liverpool during the late 1930s and early 1940s. He passed on this love of Liverpool buildings to Damien, who also inherited some of our father’s creative talents and turned out to be a very gifted artist.

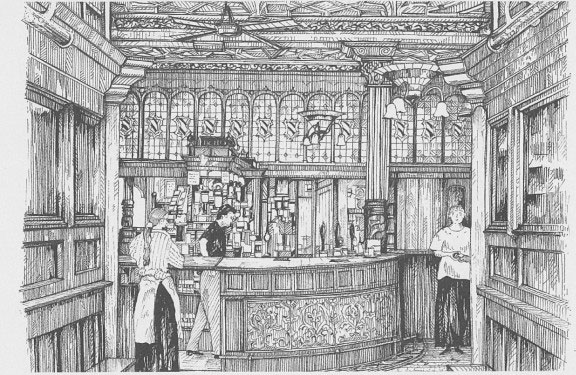

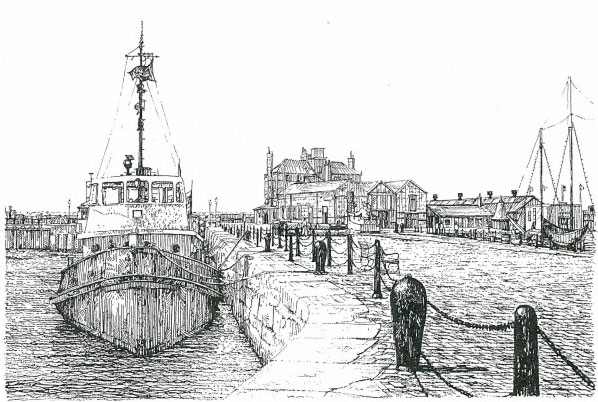

Damien sold his first prize-winning painting at the age of 12. With dad’s encouragement and guidance, he later produced some brilliant, draughtsman-like, finely detailed pen and ink drawings — some water coloured — of iconic buildings and famous landmarks in Liverpool. Using a technique taught by dad, he worked from photographs he himself had taken to ensure accuracy, proportion and perspective.

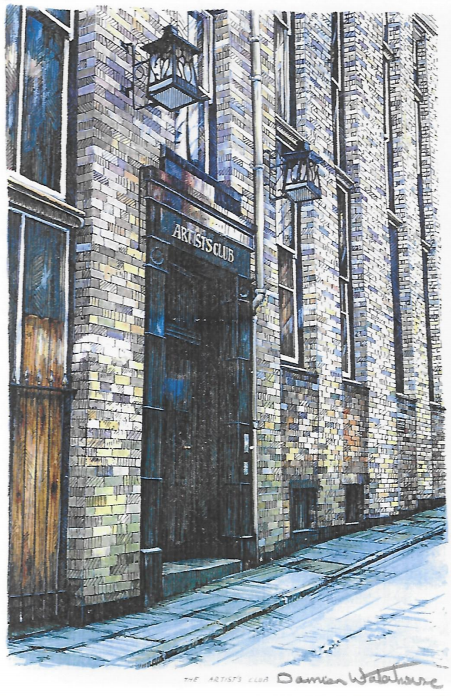

Many of the originals he sold in two solo exhibitions, organised by dad, in the early 1990s at the Artists Club in Liverpool, a private members’ establishment, where local artists and business people networked and dined, tucked away down an alley, in Eberle Street in the city centre.

I’ve been researching the relationship between my brother and father, their artistic collaboration, and their shared admiration of Liverpool buildings since Damien died of cancer in January last year. A few months after his death, I decided to re-vamp a website — which I had previously set up to promote his work — as a tribute to him and also to our father who was his mentor and sponsor.

The foundations of their working partnership were established in the mid-1980s when Damien was in his late twenties. Dad had retired as an architect, latterly working for Cumbria County Council, and moved with my mother and brother to Kirkby Lonsdale, a picturesque market town in the South Lakes. He bought the lease on a lovely, homely, oak-beamed Georgian flat on the main street above a shop, which he re-named The Print Gallery, and set up a small business, selling a variety of arty items.

At around the same time, Damien packed in his job. After leaving school aged 18, with A-Levels including Art, Damien worked in the design studio at Courtaulds in Lancaster, preparing artwork for engraving purposes in the production of fabrics, including for the likes of Liberty. After working for 10 years in industry, he decided to go freelance. This coincided with dad’s retirement and he became an enthusiastic supporter of Damien’s artwork. It was a very productive collaboration. First, with dad’s encouragement, Damien embarked on a series of pen and ink drawings of heritage buildings and scenes in and around Kirkby Lonsdale. His reputation grew and he gained several lucrative private commissions.

After the wonderful restoration and transformation of the Royal Albert Dock, which took shape during the mid to late 1980s and was officially re-opened by Prince Charles in 1988, dad was such an enthusiastic fan he revisited often and re-discovered his love of Liverpool. And over several trips, he took Damien on guided tours to take photographs of some of the most famous buildings in the City. From these, he produced a brilliant portfolio of drawings which he later exhibited and sold at the Artists Club. Cannily, dad used the original inks to make reproductions and sell in The Print Gallery in the form of calendars, limited edition prints and greeting cards.

The early 1990s were golden years for Damien’s art — capped when he was elected in 1992 as a member of the prestigious Society of Graphic Fine Art (SGFA). Damien continued to produce good work and even took over running the Print Gallery for a while when dad became ill. But then dad died suddenly in 1997, aged 76, following a stroke.

Damien lost not only his father but also his tutor, his inspiration and his direction. I don’t think I quite understood until fairly recently just how life-shattering that was for him, but I now realise that was one cause of the frequent bouts of depression that descended ever since. Another was the sudden death of our beautiful homemaker mother Sheila, from a brain tumour, in 2002.

We were both bereft. But at least I had a full-time job as a journalist living and working in London to keep me occupied. Damien must have felt very alone. In the absence of our father and the unconditional loving care of our mother, his health and wellbeing went into decline.

I could see Damien needed some encouragement to pursue his art. So, in 2006 I had a brainwave, to set up a website featuring Damien’s drawings of Liverpool — which had just been selected to be European Capital of Culture 2008. Our enterprise was given a huge boost when the City Council placed our first order, for the Capital of Culture souvenir shop, for about £2,000 worth of prints, greeting cards and postcards. I called the website Basilica Art, named after dad’s business logo, an image he drew of a basilica.

Despite the initial success, the website was not the most lucrative business but I like to think it was a source of pride and helped boost Damien’s confidence. I hoped it would inspire him to do more original art rather than just selling reproductions of previous works. He did have bursts of productivity, but, as his eyesight deteriorated with age, he could not focus clearly enough to produce the forensically detailed drawings of buildings and scenes that were his speciality.

Damien died last year, on 4 January, aged 64. He had cancer. Like many true artists, he was sometimes a tormented soul. In his later years, he developed a terrible back condition, Kyphosis, severe curvature of the spine, and his life was miserable at times. I used to go and visit him in Kirkby Lonsdale. I’d stay over for a few days and try to cheer him up with long lunches and evenings binge-watching his favourite box sets such as Poirot, Morse and Sherlock Holmes. In these later years, when he grew a beard, he reminded me — in both looks and temperament — of Vincent Van Gogh. I had the Don McLean song, Vincent (Starry, Starry Night) played at his funeral.

I don’t quite understand why, but the loss of Damien has impacted on me far more deeply than the death of my father and my mother, which occurred respectively in 1997 and 2002. For a start I watched him die, slowly, over about four months. It was fortunate, I suppose, that I was with him when he collapsed at home. I called an ambulance, and he was admitted as an emergency to the Royal Lancaster Infirmary in early October 2019. He weighed 35 kilos. After various tests, when he got the diagnosis of throat cancer he just quietly murmured almost to himself “I’m going to snuff it.”

I was with him most days while he was in hospital, and then after he was transferred in early December to Kendal Care Home, where he received loving care. These were bittersweet days. Trying to keep up his spirits, enjoy glasses of wine with our lunch. Willing him to be strong enough for some treatment. We managed Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. But he was fading away.

He died just before midnight in the first week of January. My last image of Damien alive was his gaunt face and his clear pale blue eyes reaching out to me. Pleased to see me, I think — desperate, frightened. I’ll never forget it. I’ve never loved him more.

After his death, as Damien’s only close relative, I had to organise everything: obtain the death certificate; plan the funeral service and decide on cremation versus burial; write the tribute; choose the flowers and the music; arrange the best possible send-off wake; and, a few days later, together with one of Damien’s closest friends, attend the burial of his ashes in the grave of our parents in the churchyard of St Mary’s church in Kirkby Lonsdale.

Almost immediately I had to empty and vacate his rented flat. That was like organising a full-scale home removal. All of these jobs, in turn, I treated as a project. I could not afford to be paralysed by grief. In his wallet, which he had asked me to look after when he went into the hospital, I found a photo of Damien and me in happier days on holiday in Goa — him with his desperado tough-guy look, protecting his kid sister. He must have treasured that moment. I was moved beyond words.

By the time I had it cleared, it was mid-February 2020. I then had another decision to make. Do I pay another year’s fees for the domain name and the host company of the Basilica Art website which were due soon?

I made the decision to have it completely re-designed as a final tribute and showcase of Damien’s art; a posthumous online exhibition. That became another project. When sorting and clearing Damien’s flat I discovered other original works I had never seen before or were not included on the first website because they were outside the locations of Liverpool and Kirkby Lonsdale.

I didn’t realise quite how much my dad and Damien revered the architecture of old Liverpool until I was emptying Damien’s flat, and found a book, obviously given to him by our dad, called Buildings of Liverpool, published by Liverpool Heritage Bureau, part of the Liverpool City Planning Department, in 1978. Still obtainable online, it is a treasure trove textbook — 278 pages of fascinating details about the historic Listed Buildings of Liverpool.

Some of Damien’s subjects are featured in this brilliantly illustrated reference book. They include The Liver Buildings, Albert Dock, St. Luke’s Church, the Philharmonic Dining Rooms and the Walker Art Gallery. I was inspired, on impulse, to write this piece for The Post, for readers who love Liverpool. It is a tribute to my brother Damien, my father Jack, and the result of my own sentimental attachment to the proud city and beautiful historic heritage buildings of Liverpool.

You can look at Damien’s pictures of Liverpool on the Basilica Art website here.

Comments

Latest

How Liverpool invented Christmas

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

Losing local radio — and my mum

Remembering my brother through his pictures of Liverpool

'It was only in later years, after the death of our father and then our mother, that we became closer'