Red lights and late nights in St Pauli

John Lennon once said The Beatles ‘grew up’ in Hamburg. Rosi was there to witness it

“It wasn’t all sex, drugs and rock and roll back then,” says Rosi, smiling. It’s 11 in the evening in Hamburg, and she’s dressed in a fur coat and beret to stave off the chill, stood outside her bar as customers file in and out. These days, Rosi, 81, is best known as the owner of Rosi’s Bar, based in St. Pauli. But I’m not here to talk about her experience of Hamburg’s hospitality industry — instead, I want to talk about three months in 1961 when she shared a dormitory with four Liverpudlian guys. They seemed nice enough — but she could never have anticipated that they would go on to become arguably the most famous band of all time.

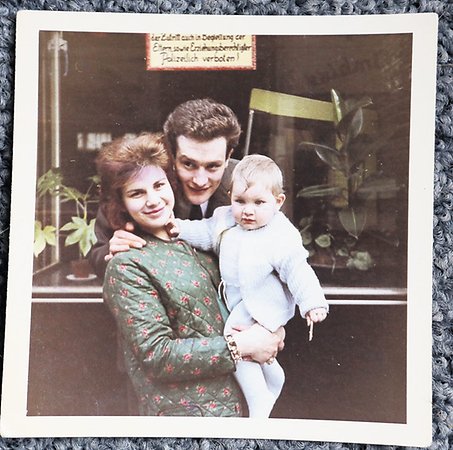

The memory that stands out most for her is of her boyfriend (and later husband), the musician Tony Sheridan drilling an 18-year-old Paul McCartney on guitar chords. “He’d be there for hours shouting ‘Give me a C, B Flat or E Minor, Paul’, and I’d ask Tony ‘Why are you being so hard on him?’ but he would say if they wanted to be musicians they just had to learn to play.” The band had arrived in Hamburg with a small repertoire of covers under their belt — around ten or 12 songs, as Rosi remembers it. Having played together in their spare time during the three years they spent studying in Liverpool, they had youthful rawness and energy but lacked the creative drive that would take them to stardom.

Back then, Sheridan (whose birth surname was McGinnity) was the biggest star in the city, if not Germany. According to the Guardian, McCartney has since referred to him as “The Teacher” and remembered the young Beatles bursting with pride when he began dropping by to watch their early performances.

It’s fair to assume that the band would have had a sink-or-swim experience, arriving in Hamburg in 1960. The St. Pauli area had long boasted a red light district attracting sailors docked in Hamburg, but thanks to a surging German economy, a huge live music scene developed at a time baby boomers were coming of age. Hamburg’s location, connected to the North Sea by the Elbe River, meant it was a port of call for international trends. A lot of young people living there in the 50s were crazy about American rock and roll, and enterprising club owners realised the closest they could get to the American sound was by hiring British bands to perform.

“It was like an eruption when the British bands first came, we just loved their sound right away. It was just incredible for us youngsters,” says Rosi, who intermittently greets customers and staff outside her bar. She’s been working as a waitress in the music clubs of the late 50s and early 60s. She was born in Hamburg during the war, and her mother died when Rosi was only five. Her father topped up his income from welding in Hamburg’s shipyards by working as a waiter in a club, and after she worked in a slaughterhouse at the age of 15, she found work in the booming club industry herself.

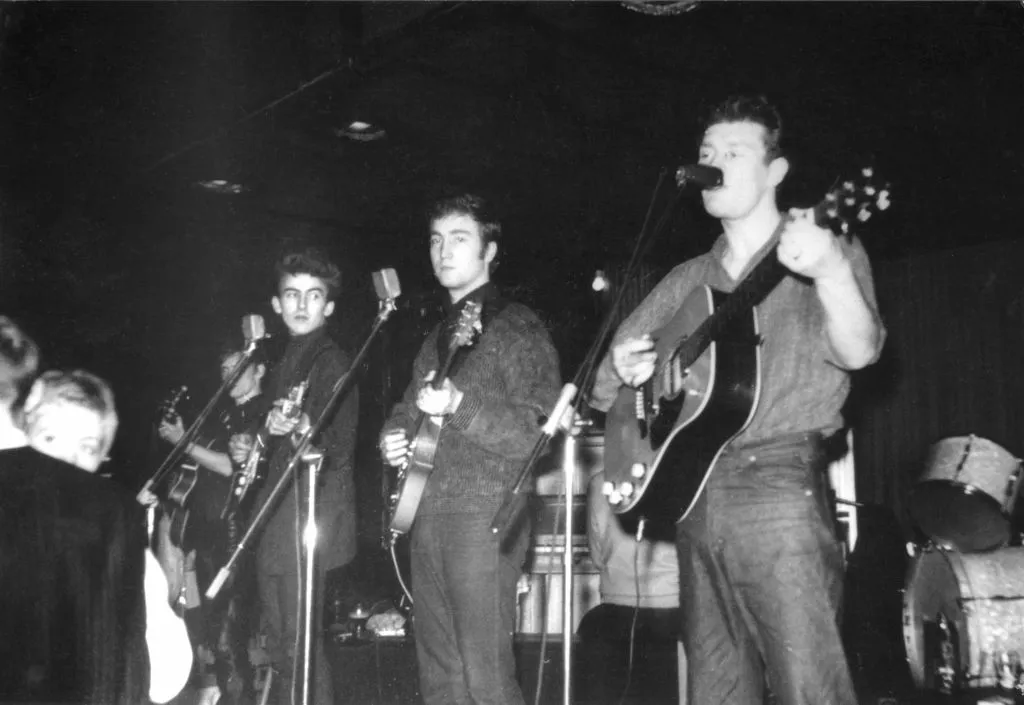

“Give us a show!” was what concertgoers, who were promised more or less constant live music, would shout. Live music was vastly better in terms of sound quality than the non-live variety at the time, and it was big business to ensure that any time potential customers walked into a club, that they could see musicians playing right away. The young Beatles soon learned the art of showmanship and would bounce around on the stages in the city with a feverish energy. “They got good after a couple of months in Hamburg. They had to,” says Stefanie Hempel, a musician who plays tribute songs and has become an expert on the band by leading Beatles tours of the St Pauli area for the past 18 years.

Their first venue in the city, the Indra Club, was a poky strip joint which still operates today as a live music club. The band members slept after performances there in the leaky basement of a cinema, minus natural light, bedsheets or heating during the freezing winter of 1960.

Unlike in England, performing all night meant precisely that in Hamburg — playing until 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning, even on weekdays. This might have been frustrating for the band, but it was a silver lining for Rosi, who says she and Sheridan would snuggle up and sleep knowing the band members would not return until the early hours. The Beatles performed 92 consecutive nights when they lived in the dormitory with the couple above the Top Ten Club from the end of March to early July 1961. The couple shared a top bunk with then-drummer Pete Best underneath, John Lennon on top of another bunk and George Harrison underneath, while Paul McCartney had an “old French divan” to himself in the corner of their shared room.

The late nights meant uppers were par for the course. A photo of the band displayed outside their first abode of the former cinema shows them grinning and proudly displaying Preludin pills. The stimulant was legal at the time and readily supplied to keep tiredness at bay. The Beatles were shocked at having to play all night when they arrived, and they would stretch songs to as long as 20 minutes to fill the time.

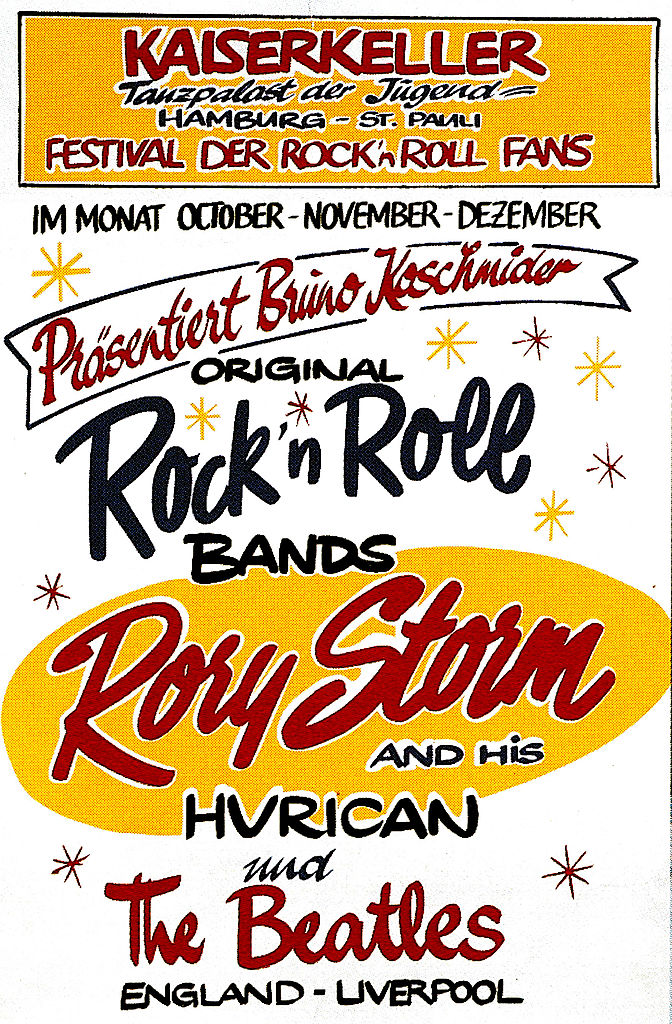

But their ambition took the edge off the working conditions. They began to command a following and in October 1960 their shows were moved to a larger venue, the Kaiserkeller, as a support act to another band from Liverpool, Rory Storm and the Hurricanes — whose young drummer Ringo Starr had a strong reputation.

The Top Ten Club offered a clear step up for the band in 1961. Its stage and sound system were improvements on the two previous venues, while the dormitory they would share with star performer Tony Sheridan, and his girlfriend Rosi, offered better living conditions.

The same year marked another big milestone, with their first recording session — even if it wasn’t under the name they’d later find worldwide fame under. The Beatles appeared as The Beat Brothers as a back-up act for Sheridan on a rocky version of My Bonnie — with the folk song being a staple crowd-pleaser in Hamburg clubs for homesick sailors.

It wasn’t all plain sailing there, though. After the band broke their contract with Bruno Koschmider, the promoter working at the Kaiserkeller, Koschmider turned sour and vengeful. He effectively had George Harrison deported for working before his 18th birthday, then a small fire started by Paul McCartney and Pete Best when collecting belongings from their decrepit lodgings at the cinema (in order to provide light, they claimed) led to them also being forced to briefly leave Germany.

Rosi’s crystal-clear memory is devoid of any notable escapades during the time she boarded with the band the following year, however. They were five young men too exhausted and professional to be more than occasionally playful (she lived with the band before the time John Lennon was reported to have played on stage with a toilet seat round his neck). She has told the German press that Lennon would spit on the walls of the accommodation and remark how the marks left by his spittle was art.

As hard as it may be to imagine a bunch of young, somewhat famous (at least on a local level) men living in a red-light district without permitting themselves the odd one night stand, discretion and mutual respect formed the cornerstone of the living arrangements. Tony Sheridan’s status as a star allowed him to sleep with Rosi in his bunk but the others slept alone with the exception of John Lennon’s then-partner Cynthia on occasional visits to Hamburg.

Rosi was not legally allowed to sleep with an unmarried man as she was under the age 21, so had a room elsewhere as an official residence. She says every now and again Sheridan would ask to sleep there, happy to risk having to hide in her wardrobe when her landlady knocked on the bedroom door.

This arrangement mirrored the legal and moral tensions at play in Hamburg in the 1960s. There were any number of seedy business attractions on offer, with peep shows, brothels and female mud wrestling performances. But all the same, the traditional conservative social framework remained strong, as shown when Rosi conceived a son with Sheridan during their time boarding with the Beatles but was denied welfare after his birth since the child had been born out of wedlock. The music would stop at 10 every evening in the clubs to allow for inspections of ID, with a curfew imposed at that time for all under 18s.

Rosi’s eyes light up when asked who the leader of the band was at the time. “Paul McCartney,” she answers immediately. “He just wanted to know everything that was going on.” She often cites the example of McCartney quizzing her on figures in the Hamburg underworld, something which was irrelevant to the band’s development (although mobsters would get front row seats to performances) but showed how intrigued he was by social dynamics.

“Paul was a very kind and approachable person,” Rosi continues. “John was John,” she says of Lennon, in a nod to his brashness, but adds that he was respectful to her, just like the others. “George Harrison had only just turned 18, but he seemed an older soul. He was quiet and you could feel this spiritual element to him already,” she says. “He was a very pleasant person to be around.”

Pete Best, the Beatles’ drummer at the time, was a very popular figure with their growing fanbase. Sound engineers at EMI deemed his ability insufficient in 1962, however, and he was replaced by Ringo Starr. “I always had the feeling Pete didn’t quite fit in with the rest,” Rosi says. “Paul, John and George were like the three musketeers, they had this clear understanding.”

Stuart Sutcliffe, a bass player with the band, left the Beatles in 1961 to take up art studies in Hamburg. “He was an artist, not a musician,” Rosi says. His influence on the Beatles’ image proved an enduring one, though. His photographer girlfriend, Astrid Kirchherr, whose place he would sleep at instead of at the dormitory above the Top Ten Club, is credited for getting them to adopt their legendary mop top hairstyles due to her interest in the Exi subculture. This flourished in Hamburg’s art schools as an expression of the spirit of French existentialist artists and writers such as Jean-Paul Sartre — “wearing dark clothes and going around looking moody” as Kirchherr later said. Sutcliffe would tragically die within a year of leaving the band, after suffering a brain haemorrhage in Hamburg in 1962 at the age of just 21.

Rosi has become a local celebrity for her links to the Beatles, but unlike many of the other venues connected to the band around the Reeperbahn, she makes no display of her personal history at Rosi’s Bar. It is one of many bars on a side strip of the Reeperbahn, two doors down from Germany’s oldest tattoo parlour. Its dark wooden panelled interior has been barely touched since she inherited the bar in 1969 from her father. Sheridan’s former wife (the pair divorced the same year she inherited the bar) no longer works until closing time at 6am as a German newspaper had reported, but continues to make all the managerial decisions, including “making sure we have good music”. A son of Sheridan’s was carrying and washing glasses, a task that kept the enthusiastic staff occupied due to the lack of a dishwasher.

Did Hamburg shape the Beatles? If we were to take Lennon’s word for it, it seems so: he once said “I was born in Liverpool, but I grew up in Hamburg.” Malcolm Gladwell would second this perspective — he cited the incredible total of 1,200 hours the band is estimated to have performed on stage in Germany in support of his theory that mastery of any skill can be achieved with 10,000 hours of practice.

I’d agree with this. After all, it was clearly an integral time in their meteoric development. The Star Club was the final, biggest and best Hamburg venue the burgeoning band played in. The band were now put up in a hotel and even began to write their own songs. They had become “Kings of Hamburg” as Pete Best said last year, and unleashed their confident performance style on unsuspecting venues in Liverpool in between their German residencies, with numerous fans thinking they were a German band when a December 1960 gig in Litherland Town Hall billed them as “direct from Hamburg”.

The Star Club is now just an empty space behind a brothel following it burning down in the 1980s. The Beatles played the final concert of their Hamburg years to a packed thousand-strong crowd there on 31 December 1962. Just 11 days later, Please Please Me, their first song to reach number one on a UK chart was released, and the rest, Beatlemania et al, is history. The boy Beatles had returned home from the excitement and noise of early 60s Hamburg as men, and the world was theirs for the taking.

Comments

Latest

And the winner is...

Losing local radio — and my mum

A place in the sun: How do a bankrupt charity boss and his councillor partner afford a “luxury” flat abroad?

Gritty, cheeky, sincere: How Martin Parr captured the spirit of Merseyside

Red lights and late nights in St Pauli

John Lennon once said The Beatles ‘grew up’ in Hamburg. Rosi was there to witness it