Raving in Bootle: How an all-night snooker club on the outskirts of Liverpool made House a home

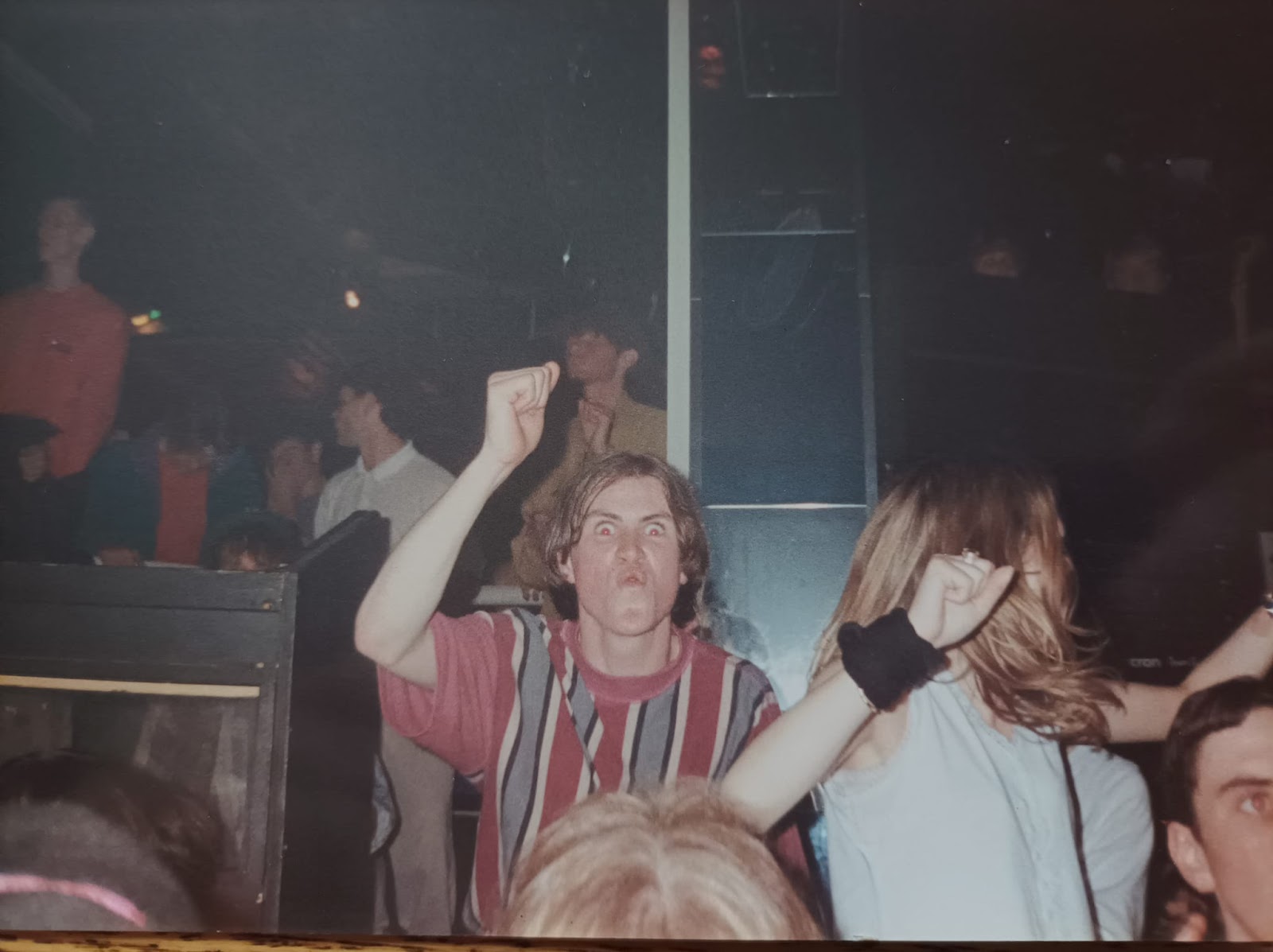

‘It was basically a big scally rave. You know, get in there, sweat your bollocks off.’

Dear members — you may not have guessed it, but Bootle was once the Acid House capital of Merseyside — with clubbers travelling there from all over the UK just to attend their one-of-a-kind all night raves. This week Ophira Gottlieb interviews legendary local DJs Mike Knowler and Andy Carroll, in order to find out just how Quadrant Park became so big, and what caused its downfall less than two years later.

But first, your Post briefing — including an update on Abi’s big story about the former regional director of Labour North West and trouble at Pensby High School.

Your Post briefing

On the grapevine: An update on last week’s story on the resignation of Liam Didsbury, Labour North West’s regional director. Anthony Lavelle (who you might recall from his bids to become mayor of Liverpool and West Derby MP) has officially been given the top job after interviews were conducted earlier this week. Interviews for the regional director position were originally meant to take place late last week (just after we published our article — read that here), however, Labour members were told they needed to be rescheduled due to unforeseen circumstances. Wonder if that had anything to do with us, eh?

Kevin Flanagan, the head teacher of Wirral’s Pensby High School, is suing a parent couple who set up a Facebook page entitled ‘"FamiliesFightFlanagan" and allegedly carried out a campaign of harassment against him. Keith and Stephanie Critchley claimed Flanagan was “bullying” their daughters and emailed Wirral Council 40 allegations about the headteacher (which he claims are false). Flanagan says the parents acted abusively towards him on multiple occasions, including one meeting in which Keith Critchley was said to be "on the brink of physically attacking" the head teacher. In a separate incident, he allegedly followed Flanagan's girlfriend in his car, beeping his horn and driving aggressively.

Nearly £18 million has been earmarked for the first phase of a new transport scheme in Runcorn. Metro mayor Steve Rotheram announced the investment this week, which would be used to install new cycle routes and footpaths as well as improve pedestrian crossings. The plans are part of Rotheram’s ambition to create a London-style public transport network that offered people an "efficient alternative to driving their car".

How an all-night snooker club on the outskirts of Liverpool made House a home

“I never imagined that in 30-odd years time we’d still be celebrating The Quad, but that’s the way it seems to be.” Mike Knowler — Liverpool’s DJ extraordinaire — is calling me from the depths of the Adelphi Hotel, shouting down the line over the sound of someone else’s wedding party in the background, and I’m shouting back from a little office room in London. Now 73, Mike is credited as one of the first British DJs to bring House music over from America, much to the delight of cycling gear outlets and small-time narcotics peddlers UK-wide. But Mike didn’t just bring House music over the pond — he and his friend, fellow DJ Andy Carroll, were two of the first to bring the genre over the Mersey, too, and to the well-known and highly-celebrated home of Acid House: Bootle.

From 1989 to 1991, Quadrant Park, aka the Quad, aka Quaddie, was one of the best-attended clubs in Merseyside — the Bootle beacon of House music, and eventual home to an all-night rave. But the club actually began its brief life back in 1985, when local businessman and wholesale steel pusher Jim Spenser decided to open a nightclub. “He had all kinds of grandiose ideas,” Mike explains. “It was to be more than a nightclub, it was to be a shopping arcade and all that.” Spenser bought a warehouse on Derby Road, and the front half he turned into a generic disco, while in the back of the building — a large, open space with a concrete floor — he held car boot sales on a Saturday and Sunday. Above these two mismatched enterprises was a third — a 24-hour, members-only snooker hall.

“By the time we got to the 80s, lots of men were working shift patterns,” Mike explains over the phone. “They might have been working nights and fancied a game of snooker before.” In fact in the 80s, Bootle and its neighbouring towns were known as some of the least economically active in the country, dominating unemployment charts; those who did work were often on irregular shifts, including all-nights and early mornings. “A snooker club that was only available in the evenings wouldn’t cut it,” Mike explains. The hall applied for a 24-hour entertainment licence in order to play music at all hours, and their application was successful, though naturally the bar was restricted to respectable boozing times. Meanwhile the club downstairs danced on at regular clubbing hours — until around 2am — to either the dismay or delight of the snooker-playing night-shifters upstairs.

The Quadrant Park club of 1985 was by all accounts nothing to write home (or, indeed, articles) about. Mike refers to it dismissively as a “Sharon and Tracy” club on multiple occasions. Nevertheless, it was successful in its own way, for a little while. The club had a capacity of 2,500 and traded decently at this level for at least three years, dwindling in popularity in 1988, and all but finished by 1989. A major catalyst for its demise was the Acid House boom, Mike explains: “That probably took its audience away.”

Prior to the Acid House explosion, mainstream clubbing in the 80s was a typically more dressed-up affair, with DJ sets often made up of popular dance hits in all but the most specialised discos. But by the end of the decade, following the revolutionary Second Summer of Love (and the revolutionary discovery of MDMA), even some of the most conventional clubbers had transformed into the baggy-trouser-wearing, whistle-blowing, klaxon-honking ravers that we all know and have mixed feelings about. Mike was one of a number of DJs who brought Acid House music to Merseyside in ‘88: he had attended the New Music Seminar in New York in 1986, and happened to be in America as the genre was breaking out.

Mike can thereby take some credit for the downfall of the first iteration of The Quad, as well as the unprecedented success of the second. However, according to the DJ, Acid House really took off across the UK when the ITV program The Hitman and Her began covering the scene. Mike refers to the show as “a clubbing programme aimed at clubbers”, as it involved the presenters, DJ Pete Waterman and Michaela Strachan, going to a club and producing an hour-long program that would be broadcast early the next morning as dancers were arriving home. At first, the programme mostly covered standard, mainstream club nights, but in ‘88 Waterman took a liking to Acid House. Suddenly, high heels and handbags were out; bucket hats and cycling shorts were in.

But not at The Quad. While dress codes were falling out of fashion all over the country, Quaddie owner Mr. Spenser was standing his ground. “I think the idea of people coming in casual clothes and trainers was a disaster to him,” Mike explains. “He was definitely a dress code man.” And so by ‘89, Quadrant Park, refusing to keep up with changing trends in music and style, was all but failing.

Meanwhile, back in Liverpool, Mike Knowler and Andy Carroll were playing Acid House at The State nightclub, which by contrast was dangerously overcrowded. Enterprising bouncers had taken to letting people in through the side door in exchange for cash. The police had said that The State was out of control, and the manager was doing nothing about it. “I mention all this ’cause it leads directly on to the revival of The Quad,” Mike explains. Mike may have been moonlighting as a pioneering House DJ, but he was also a tutor at the time, lecturing in electronics at Hugh Baird College. His students, naturally, knew of his not-so-secret second career, and they asked him if he could put a Christmas dance on for them at The State. Mike, however, was pretty certain that by Christmas, The State would have had its licence revoked by the council. Instead, he suggested that they have their Christmas dance at the all-but-empty Quadrant Park.

“So anyway, we put a dance on,” he says. “It was Christmas of ‘89. The State had closed a month before.” Rather than keep the dance for his students only, Mike suggested that they should advertise the event in the Liverpool Echo. “I told them to just put: Mike Knowler brings the sound of The State to Quadrant Park. I did a mixture of 1980s dance and Acid House. And we got 1,300 people in on a Thursday.”

“Naturally,” he adds a moment later, “that alerted the manager to the possibilities.”

Overnight, Mr. Spencer’s reservations over the lack of a dress code had mysteriously disappeared. He asked Mike to DJ at The Quad every Thursday, and Mike obliged, the first of these nights being 11 January 1990. “Same thing, we advertised in the local paper,” he says. “Mike Knowler brings the sound of The State to Quadrant Park. Only this time, I think I added: Rave Rave Rave.”

For the next four weeks, Mike DJed at The Quad on a Thursday, and Friday night was an ordinary, poorly attended disco. “We’re talking two or three hundred people on a Friday as opposed to 1,300 on a Thursday,” he says. After a month, Mr. Spencer asked Mike to DJ on a Friday night as well, and by the middle of March he decided he should take over all three weekend nights. “I said in that case, I can’t be the only DJ, ’cause what if I get the flu or there’s some kind of disaster?” Mike explains. “So at that point I said it’s important that we bring Andy Carroll in on a Saturday. And that’s how Quadrant Park was born.”

When I ring Andy Carroll — DJ Extraordinaire 2.0, from Southport — he, much like Mike, immediately launches into a misty-eyed retelling of the heyday of Liverpool House. “I’ve been doing this since I was 14,” he offers for an opening line, “and I’m 61 now.” Andy describes Mike and himself as being at the coalface of Acid House in the UK, and in Liverpool. “We were the first to play it in the city centre,” he explains. “When The State closed down, a lot of our fans were missing us.” Andy summarises quickly in comparison to Mike how the students requested the party, and how popular that party was. “It exploded. So Mike called his old mate, which is myself, and then it went from being really busy to being absolutely chocka.”

It was around this point that The Quad managers and DJs discovered a loophole in Sefton Council’s licensing terms, a loophole that would go on to transform a club night in Bootle into one of the most historically significant raves in the country. “In October of 1990,” Mike begins, “some bright spark, it might have been me, suggested we convert our 24-hour snooker hall licence into an all-night rave.”

Neither of the DJs seem entirely sure what the loophole actually was, but the working theory is as follows. The all-night entertainment licence required the venue to be a members-only club, but it appears that the local laws of Sefton Council allowed for the snooker club to make anybody a member instantly, while in other parts of the UK you would have been required to wait at least a day. Whether this was the loophole or not, it becomes apparent that ravers at The Quad were receiving instant membership to the club. Mr. Spencer had a portacabin set up just outside the premises for the purpose of endowing memberships. “You went in, they’d snap a shot on a Polaroid camera, and you’d pick up your membership card on the way out,” Mike explains. “My membership is 002. I don’t know who got 001 but I didn’t.”

At this point the actual snooker hall was, unsurprisingly, no longer well attended, and the car boot sale downstairs had for some time no longer been in operation. So Mike, Andy, and Mr. Spencer brought in some lighting effects and a huge sound system, and the disused market space was rebranded as the Pavilion nightclub — and thus began what was, at the time, the UK’s only completely legal all-night rave.

“It was basically a big scally rave,” says Andy. “You know, get in there, sweat your bollocks off.” He explains how the traditional-hour parties continued in the snooker club, and then the all-nighters happened afterwards, in the warehouse downstairs. “They’d be queueing up at six for the snooker club, which opened at nine,” says Andy, with emphasis on the three-hour wait. “That would go on until two. Then they’d empty the club out, and you’d go and queue up for the all-nighter. Though, obviously, we just walked right through.”

Mike explains that the rave scene was characterised by the willingness of ravers to travel to a club. “So if you lived in Glasgow and fancied Quadrant Park you wouldn’t be too bothered about driving to Liverpool,” he says. According to both DJs, people were travelling by car or coach to Bootle from far North Scotland and deep South England, just to attend the legendary, one-of-a-kind raves. “I had a couple of guys who used to fly in from New York,” Mike says, impressively. “Mick Hucknall was coming over from Manchester,” says Andy, less impressively. But apart from the members of Simply Red, who are frankly no markers of good taste, who were this new generation of ravers partying all night at Quadrant Park?

Jane Hector-Jones, from Wakefield, discovered Quadrant Park as a second-year art student in Liverpool. What was her connection to the club? “Well, I used to go,” she answers. “I’m just a punter, I think. That’s my role.”

“Walking into Quadrant Park completely changed everything for me,” she says. “I completely stopped going to gigs, and started going to loads of clubs.” Jane explains that the club didn’t just have a profound effect on people’s music taste, but altered the way they looked and dressed rather drastically too. “I had dreadlocks at the time,” she says. “Me and my friend Dave, we both did. We removed them the night after we first went to The Quad.” Jane cut her hair into a bob, bought a pair of Adidas Gazelles and a pair of cycling shorts, and started going raving every weekend. She wasn’t the only one. All of a sudden, a good portion of Liverpool were stomping around in Fila Trailblazers. “It was straight into that sort of Adidas, Naf Naf, Champion style. A lot of Nike,” she says. “You could walk about town and know who was going to The Quad.”

Jane explains that this was before the all-nighters began, so I ask her what it was at this point that set The Quad apart from your average rave, and she suggests the excitement and, particularly, the noise. “It was an explosion of absolute total joy,” Jane says. “Most clubs didn’t make the noise that The Quad did. You’d walk through the door and it was like Liverpool had won the cup final. Quadrant Park would hit the peak fast and it would stay there.”

She also argues that the shape and layout of the club had a part to play in the magic. “This was before the point when everybody was staring at the DJs,” she says. “Nobody was looking at them, nobody cared.” Instead, the layout of the building dictated that everyone was looking in at everybody else, facing into an epicentre. “Everybody was 100% into the music,” she says. “There was nothing else.”

It seems only right at this point in time to ask the question on every House music sceptic’s lips: how much was this ecstasy the result of the music, and how much was it the result of, you know, ecstasy?

“When I’ve analysed this,” answers Andy. “I would say that there was probably a moment when someone imported a huge amount of very good ecstasy from Holland, and distributed it very successfully.” Andy explains that the ecstasy obsession appeared quite literally overnight, and exactly alongside it came an increased interest in all kinds of House music. “It’s just what ecstasy did to you.” According to Andy, something about the effects of MDMA made people want to listen to “Jack Your Body” by Steve “Silk” Hurley all night long.

At the time, average entry into a club was around a fiver. “Beer was probably a pound a pint,” Andy says. “You could get acid for three quid and have a wonderful time. So I couldn’t really justify the idea of a whole 20 pounds for a pill.” That was, of course, until he tried a pill. “Then I went: Ok, I’ll pay for that no problem.”

However, Jane explains that pinning all the magic of The Quad and of the rave scene on ecstasy is far too easy. Instead, she says, focus should be given to the change in culture itself, catalysed by the discovery of a new drug. She cites as examples the mods and amphetamines, and hippies and LSD. “Whenever a new kind of music, and a new way of thinking comes along and hits something new pharmaceutical, it changes culture,” she says. “That’s what was happening at that point. The change was tangible. Nothing was going to be the same again.”

She also asserts the importance of rave culture in the political climate of Liverpool in the late 80s and early 90s. Thatcher was in charge, she reminds me, and there was mass unemployment, and not a great deal to look forward to. “I was signing on in Toxteth at the time,” she says. “There weren't a lot of possibilities or options. But the rave scene seemed to draw the curtains on a dark room.” Meanwhile, because of the recreational drug use, the scene was still being demonised in the papers. “You know, ‘The youth have gone insane!’ But actually, the scene gave a lot of power back to a generation that didn’t have much.”

Jane also argues that the use of ecstasy created a kinder environment for clubbers, particularly female clubbers, than the use of alcohol. “Up to that point, the sole purpose of nightclubs was for people to get off with each other,” she says. “And all of that just went, the acid house scene just cleared it out.” She explains that not just sexual harassment, but also violence and football hooliganism in clubs seemed to all but disappear. “We felt safe,” she says. “Maybe too safe. I remember walking home at 2am from Bootle to Tocky wearing hot pants and a pair of gazelles.”

However, intriguingly, Jane informs me that this feeling of safety, and of community, was at its peak before the all-nighters began. “The all-nighter was kind of where I dipped out,” she says, much to my surprise. “That edge, that hint of darkness started to come in at that point.” Violence, if just in a small way, was coming to The Quad. “A mate of mine got his shoes nicked,” she tells me. “Off his feet!”

This edge was, by all accounts, at least one of the reasons behind the very short life of The Quad. The all-nighters ran for a total of only 40 consecutive Saturday nights, from November 1990, to July 1991. One paper cited the closure as the result of a robbery and a stabbing that occurred the night before, but I haven’t found any confirmation of this. Andy claims that the club closed because Mr. Spencer got too greedy. None of the clubbers were buying alcohol, so he closed off the water taps, to make money selling bottled water. He also began letting non-members in through the door. These were tactics that Andy was very much against. “We gave him some advice,” he says, “he didn’t take any of it, and I left. I knew it would be a sinking ship from that moment.” Mike agrees. “If Mr. Spencer hadn’t been greedy,” he says “and if he’d been strict with the membership, it would have ran for a couple of years.”

But this wasn’t the only reason. In 1991, two brand new clubs opened in Liverpool city centre. One of them was the 051, which still trades to this day, and the other was the Academy. They were playing House music, they were bringing in DJs from New York, and they were in the city centre, not Bootle. “I went to the 051 on the opening night,” Mike says, “and I realised straight away that Quadrant Park was finished.” Within a few months, attendance at The Quad had dropped to a couple of hundred dancers. The physical lack of body heat meant that the club could no longer afford to keep itself warm. By July, the all-nighters were over. On New Years Eve of 1991, the club closed for good.

Quadrant Park is now demolished, and a waste recycling centre has been built in its place. There is nothing now on Derby Street to commemorate its place in the history of UK rave — not even a crap gimmick like naming the recycling plant The Quad, like they did with those flats at the Hacienda. But the club is far from forgotten. A Facebook group called Quadrant Park Reunions still has nearly 10,000 members, and is posted in daily. Arts Council England have recently funded a project called Queue Up And Dance, creating an archive through which to remember the club, and its impact on Bootle. Andy still DJs, Jane works for Factory International in Manchester, and Mike, in his seventies, thinks fondly of his short window of fame. “The club was my 15 minutes,” he says. “From January 1990 until ‘92, I was the man. I was Liverpool’s favourite DJ. And then I was no longer that focus.”

But all in all, Mike and Andy and their fellow DJs and the ravers and the ecstasy peddlers and the bike-short dealers changed Liverpool, if only in a little way. “We breathed new life into it,” says Mike. “With this new music, which was house music, and this brand new scene, which was the Rave.”

Comments

Latest

Michael Heseltine 'saved' Liverpool. Didn't he?

Cheers to 2025

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

I’m calling a truce. It’s time to stop the flouncing

Raving in Bootle: How an all-night snooker club on the outskirts of Liverpool made House a home

‘It was basically a big scally rave. You know, get in there, sweat your bollocks off.’