My beautiful laundrette

Kitty’s in Everton is more than somewhere to wash your clothes

I reach Everton at midday, during one storm or another, Isha or Jocelyn or somewhere in between, and the rain is in my eyes and the wind makes me walk all skewed about the pavement. So I’m grateful when I duck indoors on the corner of Everton and Anfield, and feel the warm air billowing out from the row of industrial tumble dryers. The smell of laundry detergent fills the room, and makes me think how I might describe the scent poetically, later, in an article. I pause a moment to catch my breath, and dry my hair on a spare t-shirt, and properly take in the launderette.

Set up five years ago as a co-operative and a social enterprise, Kitty’s acts not only as a launderette, but also as a place for people of the surrounding neighbourhoods to meet, chat, sit, attend movie nights (next week they’re doing a screening of, what else, My Beautiful Laundrette) and knitting clubs. But while self-proclaimed community spaces and hubs seem to pop up all over statistically disadvantaged areas, in churches and in town halls, plying the locals with bad tea and unsolicited advice, Kitty’s appears to have fostered a genuinely organic sense of community.

Anthony, a member of staff at Kitty’s launderette, and thereby a member of the co-operative, is the first person to approach me. Being, I would guess, a twenty-something man, he is perhaps unfairly not the type I picture when I think of a launderette employee. Our initial conversation is slightly strenuous, not least because we are both struggling to understand each other’s accents (him a Scouser, me a Glaswegian) over the rattle and hum of zippers in the washing machines.

It also becomes immediately apparent that the launderette didn’t get my email saying I’d be coming, and Anthony seems surprised and perhaps a little taken aback to be confronted by a journalist so early in the day. But after an initial interaction in which he requests I not write anything down, and tries to parse whether I might be working on a damning exposé, he eventually appears to warm to the idea of an article. After getting the go-ahead from the rest of the co-op members, he starts plying me with facts about the launderette.

Here are a few: Kitty’s Launderette is, as previously mentioned, a co-operative, which means it operates along the lines of “member-owners” — in other words, it’s co-run by all the members of staff, as well as a number of customers and people from the local community who chose to enlist as members. The input of every customer is equally welcome, Anthony adds, regardless of whether they are a member or not. It is also a not-for-profit organisation, meaning that any surplus money made by the launderette is invested back into the business itself, but again Anthony hastens to mention that they prefer the term ‘non-business entity’ as this takes the whole idea of profit out of the conversation.

Jargon aside, Kitty’s is first and foremost simply a very warm place to be. People can go there to do their washing, at rates – the customers assure me – considerably cheaper than the norm, essentially at running cost, but they can also just go to Kitty’s to have a sit down, or a natter, or a cup of coffee and a Quality Street, and use the wifi. While spaces to simply exist for free in the city are few and far between, this aspect of the launderette is not to be overlooked.

One of the main aims of the launderette is to tackle hygiene poverty, which feels like a euphemism for something too harsh to consider face-on: choosing between putting on the heating or having a shower, or having to decide whether to buy enough food to eat your fill that night, or do your laundry. And so Kitty’s also gives out free laundry vouchers through the local homeless shelters and food banks. Crucially, the business has created and continues to create a number of jobs for locals, and it quickly becomes apparent that most of the members of staff began their relationship with Kitty’s as customers.

I sit there, drying off rather slowly, drinking my instant coffee and rummaging through a box of Quality Streets in search of a toffee penny, while Anthony sends me links to various websites explaining the pillars of social enterprises, or Youtube videos about the Fair Employment Charter, all the while demonstrating an encyclopaedic level of knowledge on virtually any subject relating to social change. Intermissions from the stream of facts are provided whenever a customer arrives with a large bag of linens, or a dog bed, or a suit jacket, and at one point he goes off for a moment to the free library by the entrance of the launderette. But he quickly returns with two frighteningly large books that he recommends I read in order to understand the history of Kitty’s. He tells me I can borrow them for the day. These books are, of course, about Kitty herself.

For those unacquainted, Kitty Wilkinson was an Irish immigrant, born in the late 18th century. At the age of nine, Kitty and her family undertook a perilous journey over the sea from her home county of Derry to Liverpool, a trip that resulted in the tragic drowning of both her father and her infant sister. Still Kitty went on to live a life dedicated to the care of others. In 1832, at the height of the cholera pandemic, she began to run a laundering service from her home at the price of a penny a week, teaching the local women to clean their clothes and bed linens with boiling water and chloride of lime, and thus saving countless lives.

Her efforts eventually caught the attention of the local council, and with their help, Kitty was to open the first ever wash house in the UK, on Upper Frederick Street, a decade after opening her home to the public, in 1842. This was the beginning of the wash house movement, which led to the opening of wash houses all over the UK, effectively proto-launderettes that provided locals with the machinery and the warm, running water necessary for cleaning, and keeping cholera at bay.

The wash houses quickly fostered buzzing communities that developed naturally, unintentionally, and of their own accord. The significance of the wash houses as a place for social gatherings becomes apparent when I end up having a chat with a customer, Barbara. She’s here with her husband Steve, and it’s their first time at Kitty’s, having been recommended the launderette by a friend who uses it to wash their dog towels. Barbara still remembers going with her gran to the wash house on Lodge Lane, in Liverpool 8.

She describes her fascination with the huge industrial machines, and tells me that her favourite task there had been turning the wheel of the large mangle. But above anything else, Barbara remembers her experience of the wash houses as consisting of “mostly women having a gab.” The wash houses of the time were used exclusively by women, who took the opportunity to chat and exchange stories. As well as the washing facilities, many wash houses were equipped with a cafe and a creche, giving the women doing their laundry a rare opportunity to catch up with each other. According to Barbara’s grandfather, the women in the wash houses broke the news of the D-Day Landings before the papers did.

But still, while many women remember the wash houses fondly, it’s worth remembering that they were communities effectively built on exclusion. These women were not traditionally expected or allowed to meet in pubs, and they would have had few opportunities to socialise, what with being expected to constantly maintain the household, or look after their children. Their brief opportunity to convene was while they were performing their prescribed chores. On top of this, the wash house community would have been an extremely homogeneous one, composed almost entirely of white, working-class women.

This is a very noticeable difference between the wash houses, and Kitty’s Launderette. In my time spent here I fail entirely to identify a certain type of customer to utilise the facilities. In terms of gender, there are more men than women coming through the launderette doors which I, perhaps naively, find pleasantly surprising. Elisha, another employee at Kitty’s, tells me that a possible reason for this is that quite a few men don’t know how to do their own laundry, and leave it to the staff to do it for them at an additional charge.

Later a third employee, Kirsty, backs this up when she tells me that “sometimes a man comes in and I’m like — are you doing your washing yourself and all?!” And sure enough, when I ask Barbara and Steve what they’ve come here to wash, they admit it’s their son’s bedding that he’s brought home with him from uni. I must say however that in the time I’m here, I see quite a few men do their own laundry all by themselves, and fairly competently, and the gender balance of the employees appears to be about 50/50.

The people who work at Kitty’s come from a range of different backgrounds. The boys, Anthony and Dylan, both started off as customers before they became co-op members, and took on jobs there. Dylan “stumbled” into the launderette in late April of last year, and “very quickly realised that Kitty’s was weird in the same way that [he] was,” though he does not elaborate as to just what particular strain of weird this is. The progression from customer to employee seems to play an important role in Kitty’s success, as it means that the launderette is eventually run by the locals that actually use it in the first place. There is an appropriately blurred boundary between the people who use Kitty’s and those living in Everton, and as Anthony notes, “it would be silly to think that community ends at the launderette door.”

Kirsty began working at the launderette shortly after the doors first opened. Before that she was a manager at Asda, but by her own admission spent most of her time employed there on various bouts of maternity leave. She tells me that her mum used to work in a wash house – a friendly, safe place where women would leave their babies in prams outside, and she asserts that anyone could do that at Kitty’s too, if for whatever reason they felt inclined to.

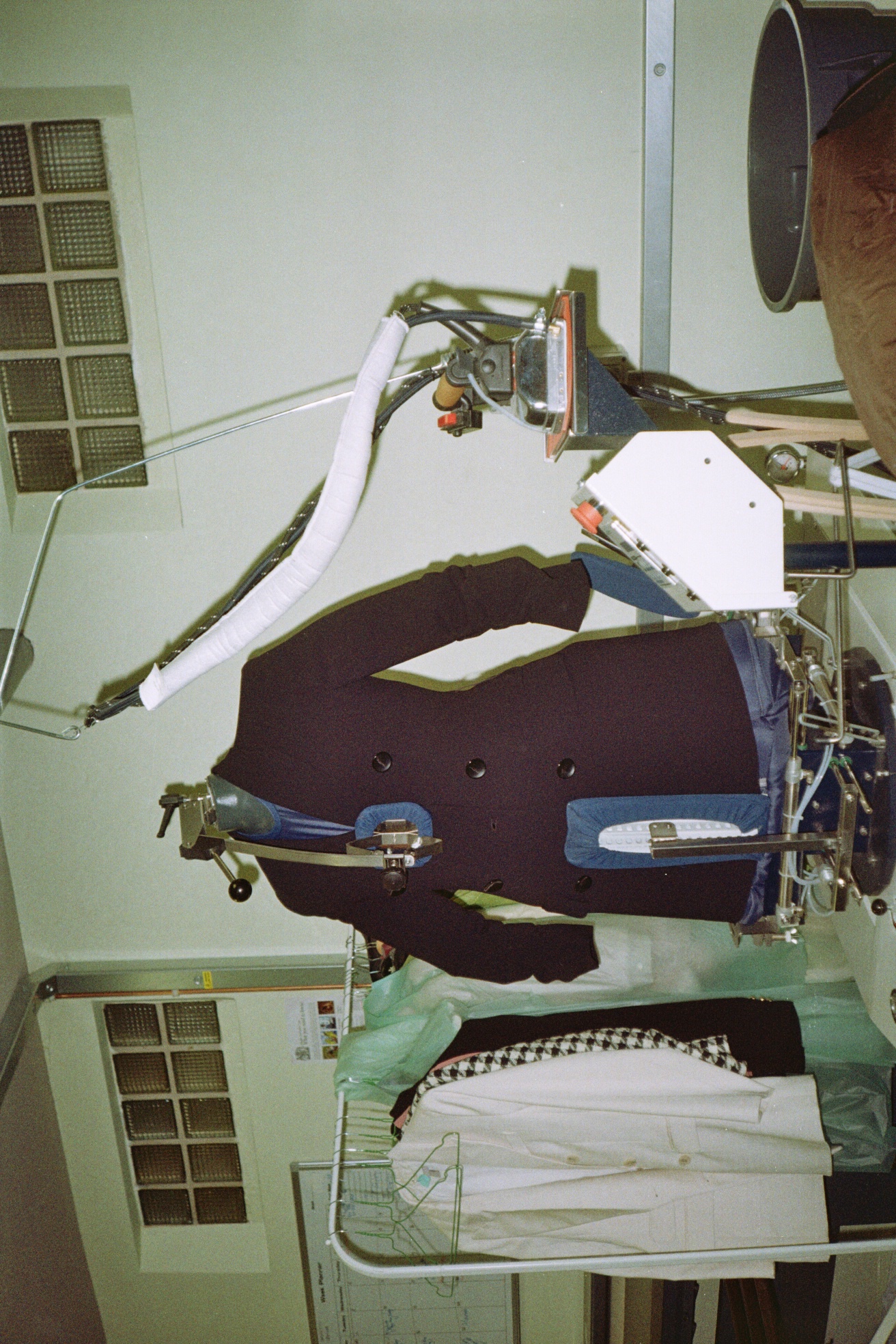

While she shows me around the launderette and explains the various machinery, including the bizarre ‘Jacket Former’ – an automatic suit-jacket ironing device that looks like something straight out of Wallace and Gromit – she tells me about the relationship she’s built with the various customers over the years. By now she knows most of her customers not only by name, but also by laundry. There’s one woman, a fashion designer, whose washing Kirsty can immediately identify because she only shops for pyjamas at M&S.

This oddly intimate worker-to-customer relationship becomes all the more apparent upon the arrival of another Anthony, this time a customer, who whirls out of the storm and into the launderette rather dramatically and immediately begins sharing details about his love life with anyone within earshot. Anthony moved to Everton from Old Swan during lockdown and, like many others who moved anywhere around that time, he found himself quickly isolated by the government regulations. He heard about Kitty’s through word of mouth, and ever since then he has been coming here regularly. “Sometimes I don’t even do me washing,” he tells me, but today he’s washing his work uniform as, being a bus driver, “the stuff always smells of diesel.”

Anthony (the customer) proves very useful to chat to, as before discovering Kitty’s he would regularly use Prima launderettes, and is good on the difference between the two. Unlike traditional wash houses, Anthony insists that modern-day launderettes are deeply unsocial spaces. Most Prima launderettes, he tells me, have bluetooth-operated machines, meaning that there is often absolutely no human interaction involved. He describes the launderettes as clinical and sterile, but here at Kitty’s he claims to have had an entirely different experience, a claim that is shown plainly to be true by the fact that he spends most of his time here nattering with Dylan about an ex-lover, and showing Employee-Anthony Tik Toks on his phone.

By the time the rain has subsided and Customer-Anthony and I go off to get a pie, the reasons behind Kitty’s success as a community space seem quite apparent. Even though Kitty’s was initially created by an outsider to the Everton community – Grace, from Yorkshire, who unfortunately I didn’t get the chance to meet – it has integrated itself successfully first and foremost by performing a function that is genuinely necessary to the community: that of being a launderette.

But more than that, there is no condescending sense of charity present in Kitty’s. Indeed it is not a charity and the word doesn’t appear anywhere within the organisation. Earlier in the day, somewhere between my third and fourth instant coffee, I have an interesting chat with Employee-Anthony about Kitty Wilkinson’s nickname, “The Saint of the Slums”, a nickname that we both agree to be problematic.

Kitty is an inspiringly kind and caring person, but she was also the only person with the privilege of having a boiler on Denison Street, where she lived. She shared this privilege, and the privilege of her knowledge, with her neighbours, but she did so out of necessity, during a time when people would die without her help. Moreover, Kitty was an immigrant to her community, but she integrated herself and quickly became a part of it. I personally can’t imagine she would have enjoyed being called a saint anymore than she would have appreciated her neighbourhood being referred to as a slum.

Kitty’s Launderette operates on the exact same principles. It too arrived in Liverpool as an outsider, but with a little time and effort was adopted as a local. Kitty’s, like Kitty herself, does not provide charity, but instead provides the means to a necessity. When I finally head off into the outside world, I’m a little deflated to be leaving. The storm, at least, has stopped, and my jacket has almost entirely dried off, but I’ve grown so accustomed to the whirring of the washing machines that the streets seem eerily quiet. Before I leave, I promise that next time I’m in the neighbourhood I’ll drop by, and I am certain this is a promise I will keep. It is, by now, abundantly clear to me why people would drop into Kitty’s Launderette and not even do their laundry.

Comments

Latest

Northern Powerhouse Rail is back on track. We think...

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still play every Saturday

Does Liverpool have a ketamine problem?

My beautiful laundrette

Kitty’s in Everton is more than somewhere to wash your clothes