'Love is fish and chips on winter nights': why were the Liverpool Poets so obsessed with food?

Feasting my way through 'The Liverpool Scene'

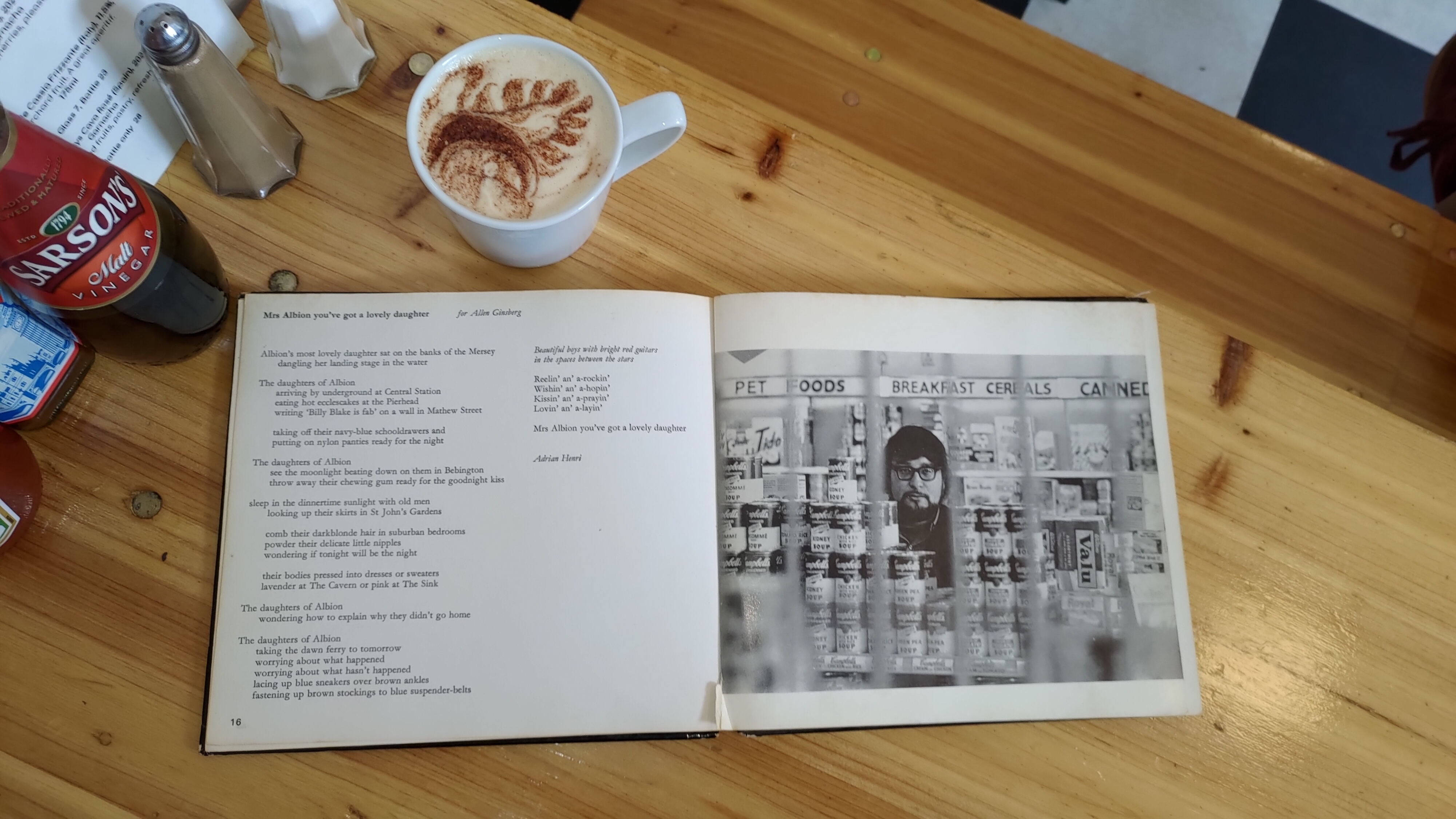

There is a famous photograph of Liverpudlian poet Adrian Henri looking very serious in a supermarket. In the picture we look at Henri, complete with beard and gawky haircut, through the bars of a supermarket window, and he gazes unblinkingly back through thick-rimmed and even thicker-lensed glasses. Stacked in front of Henri are tins upon tins of Campbell’s soup — tomato, chicken, green pea — and right above his head, directing shoppers to their aisles in block capitals, is that familiar and crucial word: ‘BREAKFAST’.

Breakfast, soup, and supermarkets all seem to find their way quite naturally into the work of The Liverpool Poets. The three doe-eyed darlings of the movement — Henri himself, Roger McGough, and Brian Patten — spent the 60s conjuring poetry out of the everyday, and would appear to regularly ransack their store cupboards for opening lines, or doss about eating pastries in Kardomah cafes until verses inevitably struck them. This, at least, would explain why so many of their poems are about food and food-related paraphernalia, and barely a page goes by without mention of kitchen utensils, cornflakes, or fish and chips. Even their performances would regularly occur in basement coffee shops and cigarette-scented pubs, so that each poem would not only be filled with, but also accompanied by food and drink.

In this sense, the photograph of Henri is a little on the nose to say the least. It’s also an incredibly obvious allusion to pop art’s most incredibly obvious symbol — the Campbell’s soup can — which feels appropriate. After all, the Liverpool Poets were Pop-Poets. Effectively they functioned as poetry’s answer to the boy band or, more specifically, the Beatles, trading in the skiffle band’s washboards and jugs for equally accessible, equally everyday poetry material like bus tickets and unsalted crisps. Their idea was to write poetry about anything and for everyone — everyone, that is, except the high-end literary magazines, who were only excluded from the target audience after repeatedly rejecting the poets’ earlier work.

So, last week I paid a visit to the city to eat with the Liverpool poets. I came brandishing the anthology The Liverpool Scene: A large, flat compilation that features the poets’ work alongside context-free snippets of them saying things like “Liverpool is a sort of — it’s a city.” (Brian Patten, 1960-something). The collection also includes numerous photographs of the poets looking broody and wearing corduroy in various domestic settings around Liverpool, with Henri and the Soup Cans not only gracing the front cover but also taking up an entire page within.

As well as the anthology, I came with a number of recommendations for chip shops, caffs, and Guinness-serving pubs. My goal was to discover why it was that the poets put so much food into their poetry, and exactly what they were using the food to say about the nature of love, lunch, and Liverpool. Here, below, and divided into meal-sized portions, are my findings.

‘Without you Sunshine Breakfast would only consist of Cornflakes’

I begin my day of dining with Breakfast in Maggie May’s, a cloudy Bold Street cafe where the tiles match the table covers. The poets are here with me, sprawled rudely across the yellow-checked table and banging on about their usual subjects of interest: buses, sex, and cereal.

Around me, elderly locals drink tea out of white mugs and leave circles of milk all over their crosswords. In one corner, a gaggle of Americans are trying the cafe's famous Scouse while talking loudly about the Beatles. This is precisely how I’d always imagined Liverpool to be.

Cafes were a fundamental feature of the poetry scene in ‘60s Liverpool. The live poetry readings allegedly started in Streate’s cafe, a basement coffee bar named after a painting of “some Victorian, Liverpool Victorian person, Mr. Somebody Streate” — just one example of the many informative anecdotes to be found within the pages of The Liverpool Scene. The cafe quickly built a reputation for itself, and became a regular haunt for poets, jazz musicians, students, and various other twenty-somethings in turtlenecks.

I order myself scrambled eggs on toast and coffee — nothing for the poets. The three of them already seem to have more than enough profound statements to make about breakfast.

“Without you…” Henri writes in his poem, aptly titled “Without You”.

“Without you there’d never be sauce to put on sausage butties.”

“Go on.” I say.

“Without you Sunshine Breakfast would only consist of Cornflakes.”

The poem is effectively a lot of lines following this format: Without you, [X] mundanity would be even more mundane. It’s interesting that the food mentioned within the poems is almost always banal and easily accessible: instead of scouse and Liverpool tarts, we’re doused in Coke, candy, and Kellogg’s. This is quite possibly the result of the poems having been written in post-war Liverpool, as the city emerged from years of rationing and scarcity into the dazzling world of American sweets on the shelves of Tescos.

But simpler, non-Yankee foods make their regular appearances too. In this poem alone, sausage butties, green apples, and crisps are all transformed into confessions of love. This metamorphosis-by-verse — turning the banal into the romantic — seems to sit at the heart of the poets’ food fixation.

I finish off my eggs on toast and, nursing the cold dregs of my coffee, sit for a while, digesting both my food and Brian Patten’s somewhat gloomy poem “After Breakfast”:

After breakfast,

Which is usually coffee and a view

Of teeming rain and the Cathedral old and grey…

In this poem, Liverpool is for breakfast. The poem is set in an attic room on Canning Street, previously in Liverpool 8, the room that Patten moved into after leaving home at the age of 17. Despite the miserable description of the view, these opening lines actually boast of Patten’s change of status. A trendy attic room in Liverpool 8 was something to be envied, and coffee was still hard to come by in early ’60s Liverpool and was associated with a particular class and type, namely bohemian, beret-wearing beatniks.

The poem’s final verse consists of a single, dramatic line:

“The rain will inherit you – lonely breakfaster!”

Eating breakfast, in fact consuming any meal alone, is another recurring preoccupation of this collection. The poets depict eating together as a performance of love, and eating alone as the pinnacle of desperate solitude — the most tragic thing that can possibly happen to a person. So it’s refreshing that in this poem at least, the solitude is romanticised, and looking around at my fellow lonely breakfasters in Maggie May’s, munching on toast and jam and wearing ties in the morning, I can sort of see why.

‘At Lunchtime, A Story of Love’

After breakfast, I take a wander through the city, past statues and buskers and that street where every single bar is a karaoke bar so that at any given moment you can hear at least five different renditions of “A Little Respect” by Erasure.

Refusing to use Google Maps, guided only by the sharp tang of perspiring tourists, I find my way to the Pier Head. The area is cited several times throughout the collection, mostly by Adrian Henri, possibly due to the fact that Henri is the only poet of the three originally from Birkenhead, and the port would have been his first encounter with, and his entry into Liverpool.

Henri has a poem that is rather oddly named “Mrs Albion You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter”. In the poem, Henri writes about “eating hot ecclescakes at the Pierhead”, which is also very odd, because this is the only mention of a specific regional food in the entire collection, and it isn’t even from Liverpool.

I search for a while for any sign of an elusive eccles cake vendor along the waterfront, and come up empty, which is good because I don’t like eccles cake, and it makes no sense to eat it in Liverpool anyway. Eventually I settled for a buttie van selling hot baguettes and sugar-coated donuts.

While eating, I turn my attention to Roger McGough, and his poem “At Lunchtime, A Story of Love”. The poem is more of a very short story than a poem really, and reads a little like McGough is trying to impress you in a playground with a very obvious lie. He spends the poem telling us about the time he convinced an entire bus-full of strangers to sleep with each other, and with him, by telling them all that the world is about to end.

“When the word got around that the world was coming to an end at lunch time, they put their pride in their pockets with their bustickets and madelove one with the other. And even the busconductor, being over, climbed into the cab and struck up some sort of relationship with the driver.”

I have never been entirely convinced by the classic trope of pre-apocalyptic love making, simply because it doesn't seem all that practical. However, I found myself taken by the poem-slash-story, and most of all by the significance of it being precisely ‘lunch time’ when the world is to end.

There is something downright impolite about disrupting the unwavering consistency of lunch time with the threat of a nuclear apocalypse. The world ending is unpleasant at the best of times, but just like that? Just as we were sitting down to eat? It’s a bit rude.

Still, there’s some sense to it. These poems were written at a time when the threat of nuclear warfare felt as everyday as lunch, and ‘the bomb’ features in this collection as regularly and as casually as crisp packets.

And if that threat was constant and commonplace in the 60s, it makes sense that it should at least be used as an excuse to sleep with strangers on the bus.

‘Love is fish and chips on winter nights’

Although I received a number of recommendations for various chippys across Liverpool, I end up ignoring all of them, taken in by a seemingly serendipitous news snippet outside ‘Yanni’s’ claiming that the city-centre chip shop is the greatest in all the land, or something to that effect. Reader: it isn’t. I sit down with a friend, and we dig into cod and chips and mushy peas, eaten out of bright blue cardboard boxes. Around us are mostly couples, opening packets of tartar sauce with their teeth, sitting in silence.

As we eat, we leaf through the anthology with greasy fingers, and count the exact number of times The Liverpool Poets manage to squeeze fish and chips into their poems. The verdict: Fish and chips and/or chippys are mentioned a somewhat unusual seven times throughout the anthology, but the really bizarre thing is that five of these mentions come specifically, once again, from Adrian Henri. This means that just under a quarter of his poems in the collection mention the dish.

Perhaps Henri’s most sentimental chip-related quotation comes from his poem “Love is…” which features the unreasonably English line “Love is fish and chips on winter nights”. This line is representative of virtually every other mention of the dish throughout Henri and the others’ poetry, as in the entire collection the dish doesn’t merely represent love, it is love, and a very English strain of love at that.

But it’s not just Henri who is hooked on fish and chips. Even though McGough only mentions the meal once, it is probably the most well-known of the Liverpool chippy poems. His poem “Vinegar” goes, in its entirety, as follows:

“sometimes

i feel like a priest

in a fish & chip queue

quietly thinking

as the vinegar runs through

how nice it would be

to buy supper for two”

This poem contains three classic features of the poets’ work: food, loneliness, and English stereotypes. It would be easy enough to believe that they came up with much of their subject matter by simply spinning a massive wheel of Quintessential British Items until it eventually settled on ‘pudding’ or ‘saucers’ or something like that. The repeated use of fish and chips can at times feel like an unnecessary and unsuccessful attempt at capturing a nationwide Britishness, and forgoing scouseness in the process.

Still, it has to be said, this poem is very sweet. I like it, it is a good poem. I’m just glad I brought a friend along for the meal, otherwise by this point the repeated insistence that eating alone is very horribly terribly depressing might just have started to get to me.

“She is as beautiful as bustickets / and smells of old cash / drinks Guinness of duty / eats sausage and mash”

Chippy tea over — we head to the pub. Ye Cracke is a very traditional pub in one sense: traditional ales, traditional red sofas, traditional pub blokes sat on their own drinking porter and staring into space on individual tables when they could all just be sat together. But it is also a very modern pub in other ways, with each wall adorned with beautiful and presumably local artwork, except for one which boasts a picture of Prince Andrew with the word ‘NONCE’ written above his head in block capitals, poignantly reminiscent of the ‘BREAKFAST’ in Henri’s picture. We went in, a few of us now, and they all ordered a Guinness and I ordered a Guinness and black.

I only actually found out while sitting in Ye Cracke that Adrian Henri mentions the pub in one of his poems. Finally! I get to sit where he sat, drink where he got drunk, write bollocks in a notepad where he wrote world-renowned poetry. In the poem, titled “Poem for Liverpool 8”, Henri describes himself as being “drunk jammed in the tiny bar in The Cracke”. Just to think — in a few short pints that could be me.

Pints, naturally, feature frequently in the anthology, and of all the pints the sacred Guinness is mentioned the most. The drink plays a peculiar role in the poems. So much of their poetry is at its core about women and about love, and Guinness just doesn’t seem to fit with their image of either of these things, but still it pervades even their most romantic poetry in a curious way. Take Roger McGough’s poem “My Bussductress”. The poem is about a bus conductor who dreams of being a stripper, and twice it contains the lines:

“She is as beautiful as bustickets

and smells of old cash

drinks Guinness off duty

eats sausage and mash.”

In just four short lines, McGough manages to mention quite a large amount of things and, of course, most of those things are food and drink. They are also all everyday and even ugly things, things we don’t typically associate with love.

But McGough doesn’t use Guinness to dampen the romance of the poem. Instead, Guinness does to romance just what The Liverpool Poets do to poetry. Henri, McGough, and Patten took something that was once considered to be only by and for an elite few, and they managed to turn it into something simple and commonplace, something flawed and dirty and all the better for it.

Comments

Latest

Get ready: the Aloft trials are coming

Michael Heseltine 'saved' Liverpool. Didn't he?

Cheers to 2025

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

'Love is fish and chips on winter nights': why were the Liverpool Poets so obsessed with food?

Feasting my way through 'The Liverpool Scene'