Jacaranda Records wanted to ‘change the industry’. How did it go so wrong?

‘I am a son of an immigrant and I grew up in the arse tit of nowhere in Seaforth. I am no star fucker’

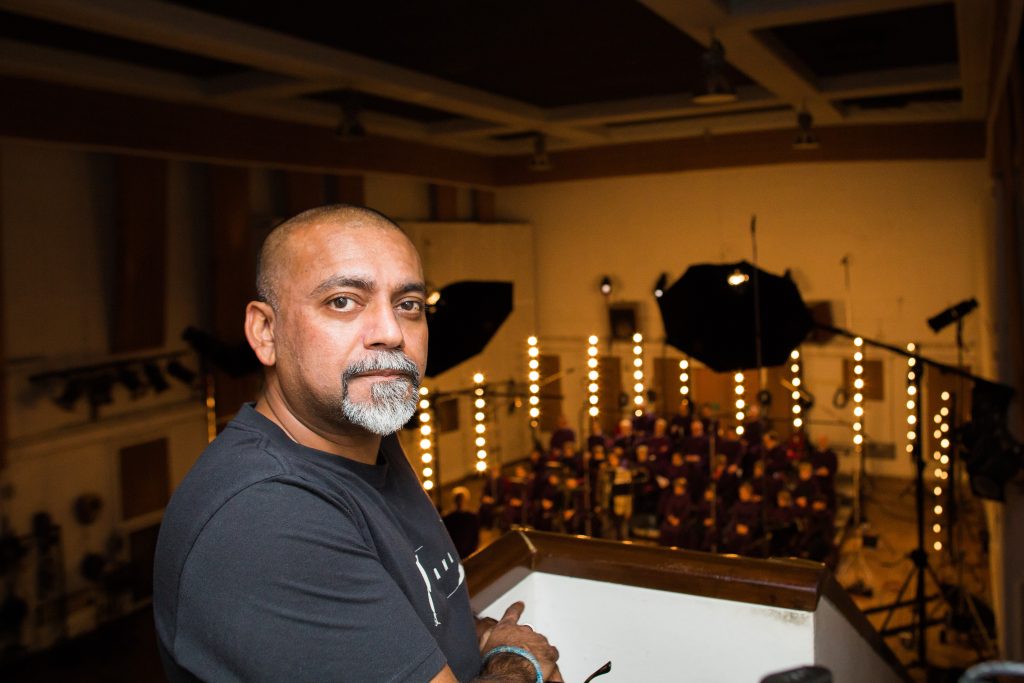

Dear readers — today’s story comes from the heart of Liverpool’s music scene. At its centre: Ray Mia, a maverick producer and self-styled ‘capomaestro’ of Jacaranda Records, an upstart label formed in 2018 with plans to “change the music industry”.

Jacaranda Records arrived on the scene all guns blazing. Taking the name of the iconic Jacaranda Club, where The Beatles once rehearsed, in Mia’s own words there was the opportunity to tell “this amazing untold story of essentially the birthplace of the Beatles” and craft an exciting new legacy in the process.

Alas, no such thing happened. The fallout of Mia’s involvement, according to former staff at the label, has been the derailing of the careers of two promising bands. They say Mia lured the artists in with a series of outlandish promises, only to make them sign away their rights in unethical contracts. “I feel an immense amount of shame and guilt about what went on and to have fallen for it,” the young manager of one band told us.

Mia denies this strongly, saying he made no such “promises” to any of the artists, and instead invested £500,000 of his own money into the label, providing opportunities to the young musicians which they were unwilling to work hard for.

“Most of the people that you’ve spoken to are opportunists,” he says. “Go and have a look at their careers. Go and have a look at who they are and where they are now. Then go and have a look at mine. Go and have a look at what I’ve done.”

That’s the subject of today’s story. To read it, you will need to be a paying member of The Post, and if you’re not one of those already, this would be a great day to jump on board. Not only can you read Jack’s story about Jacaranda Records, but you will also get lots of exclusive members-only stories from us, as well as access to the whole back-catalogue. As we’ve seen over the past year, local news is in a tough spot right now with many outlets struggling to survive. If you appreciate the work we do, consider supporting us by signing up.

Your Post briefing

The mother of murdered schoolgirl Brianna Ghey has backed the naming of her teenage killers while urging compassion for their families. Two teenagers, who were 15 when they killed Brianna in a "frenzied and ferocious" attack after luring her to Culcheth Linear Park in Warrington, were found guilty of murder in December and are set to be sentenced. Brianna's mum Esther said the pair showed no remorse in court, but that she feels emotional when thinking of their parents. “I saw how they were in court and how distraught when the verdict came through, I could see myself in them, the way I felt when Brianna had been murdered.”

Some retail news from a prime city centre spot: the old M&S building on Church Street (vacated since M&S upped sticks to Liverpool ONE) has a new tenant lined up: Sports Direct. The iconic Compton House building was M&S’s home for a century. We explored the various ramifications of the switch up for the changing face of the city centre way back in the heady days of 2022 — revisit that one here — and now we finally know what will be taking its place. Pleased? Disappointed? Let us know.

Do you think Liverpool is the world’s best city? Well, you wouldn’t be far off — at least according to Time Out, who have us in 7th place, sandwiched nicely between Mexico City (6th) and Tokyo (8th) — and, crucially, a whole eight places above Manchester (15th). “There's more to Liverpool than Beatles tours and football matches,” Time Out reassuringly informs us. “In fact, it's one of the best places in the world to go for a guaranteed-good-time.” Reactions to unexpected result on Reddit varied, from the positive (“Liverpool is such a vibrant and beautiful city with amazing architecture and so much culture”) to the somewhat more cynical (“Looks out through the net curtains at County Road… nods sagely”).

“It just has one purpose — reputational damage. I’m a big boy, say what you want.”

I’m talking to Ray Mia, a Sefton-born music producer who returned to Liverpool five years ago to form a record label, Jacaranda Records, taking the name of one of the city’s most iconic venues. Mia’s former colleagues at the label have alleged the exploitation of local artists, in a series of conversations with The Post. Now Mia himself has agreed to an hour-long interview to discuss their extensive allegations. He’s come out swinging — he is not, he insists, “cowed by bullies”.

Mia’s accusers say that he and the label arrowed in on a group of young and naive artists, promising them fame and fortune in an attempt to get them to sign away their rights through unethical contracts. They say the fallout of Mia’s involvement in the Liverpool music scene has derailed the careers of two exciting young bands.

Mia, on the other hand, says he pumped £500,000 of his own cash into the label only to be let down by artists who weren’t willing to put the effort in. Over the course of our interview, he repeatedly urges me to compare the successes of his own career with the “serial objectors” attempting to tarnish his reputation. “Liverpool is full of troubadours and bullshiters,” he tells me.

Grand ambitions

Liverpool’s Jacaranda is the sort of music venue people might describe as “storied”. The place has history, that’s for sure. Opened by The Beatles’ first manager Allan Williams in 1958, the venue was a launchpad for the careers of many artists, like Gerry and the Pacemakers, as well as a frequent haunt of the Fab Four themselves. In 2018, a maverick producer-cum-entreprenuer decided he wanted to tap into that rich past. He wanted ‘the Jac’ not just to be a place with history, but a pioneering force of the future. He wanted to start a record label. He wanted, in his own words, “to change the industry”.

Ray Mia announced himself to Graham Stanley — owner of the Jacaranda club and record store — with a long email setting out his vision. An Oxford alumnus boasting a successful career in music and television (having worked for Universal as well as a previous job at the United Nations), Mia asserted that he could bring “unheard of resources” to the table, thanks in part to his business relationships with “US West Coast tech companies”. If Stanley wasn’t yet convinced he should bring him in, Mia may have sealed the deal with the following comment: “I’m a workaholic and I don’t mess around.”

Stanley is keen to reiterate the distinction between the Jacaranda, his club and venue, and Jacaranda Records, the record label. He says he agreed to let Mia use the Jacaranda name “in good faith” in exchange for a small percentage of the label’s shares. Mia would go on to describe himself as Jacaranda Records’ “capomaestro”, a Sicilian term for ‘master builder’. In the original email, he wrote: “Everything I’ve done is based entirely on hard graft and being able to deliver what I say I can deliver (on time and under budget). I am a son of an immigrant and I grew up in the arse tit of nowhere in Seaforth. I am no star fucker”.

One staff member hired to work at the label recalls Mia, in the early days, pulling everyone together for a meeting and laying out his vision to “change the music industry”. “He stood up and went: ‘There’s no room in this room for egos because I’m the only one with an ego,’” the staffer says. Another time, Mia apparently said that he was investing his children’s inheritance to try and make the project work: “If you put yourself between me and my children, I will gut you like a fish,” the staff member recalls him saying.

“He was very, very charismatic,” says the same former staff member, who worked for the new team in 2018. “And Graham Stanley would talk about how it was ‘one big family’. By the end I wondered if it was the Manson Family” (to be clear — they were not alleging any criminality).

The label’s strategy was to work with young artists who they believed had undiscovered potential. A series of “label showcases” were held at Phase One (a new venue opened in 2018 by the Jacaranda team), with the performing artists being told they had a chance to be signed. Mia was the judge of who would or wouldn’t get an offer. Two bands, named Spilt and Shards respectively, caught their interest, as did the solo artist Tracky.

Spilt were perhaps the most promising of the trio, given they already had more than 1.5 million Spotify streams on a single song — a notable achievement for a local, unsigned band. Mia, having been informed about the difficult home lives of some of the band's young members, allegedly promised to set them up in a house in Liverpool, according to several of the label’s former staff. “These were really vulnerable kids,” says one. Mia also bought them new drum kits, guitars and paid off the bass player’s hefty rollover train fine.

Staffers claim that Mia made other promises and lofty suggestions that did not come to pass (something that he disputes). The house in Liverpool, an escape from the difficulties of their old lives for the Spilt members, never materialised. Neither did a billboard campaign that had been suggested for Tracky. Perhaps less surprisingly, neither did the talk of a Vogue cover for the artist Niki Kand. Nor the purchase of Parr Street Studios, nor Iggy Pop coming to record at Parr Street Studios, nor Jacaranda Records remixing The Ramones back catalogue.

Mia “categorically refutes” that he “promised” these. These were merely ideas, he says — various business plans he had, par for the course in the industry. Buying Parr Street Studios wasn’t a promise — Mia says that the asking price was too steep at £2 million, and the idea of getting Iggy Pop to play there was simply that he knew the musician’s producer Andrew Scheps. The house for Spilt wasn’t a promise either — he says he looked at a number of houses before deciding, alongside the band, that the money would be better spent on rehearsal space. Nor was the Vogue cover for Kand (this is a misunderstanding, he says, arising after a staff member working for the famous music entrepreneur Simon Fuller had told him an image of Kand looked like something from Vogue). He reiterates that none of these were “promises” at all.

But his ex-staff see things differently. “It was horrific,” one says. “He basically got all these kids and told them they were going to be famous.” It began to raise a question among the Jacaranda team: is Ray Mia really who he seems?

Latest

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

Losing local radio — and my mum

And the winner is...

Jacaranda Records wanted to ‘change the industry’. How did it go so wrong?

‘I am a son of an immigrant and I grew up in the arse tit of nowhere in Seaforth. I am no star fucker’