Irish women struggled to get an abortion at home. Could a group of Liverpool feminists be the answer?

‘Why should they have to suffer?’

By Mollie Simpson, with additional reporting by Anna Shepherd

At 17, Linda Pepper saw things very clearly. Sex wasn’t just fun or love or adventure, it was responsibility. Because what if the condom split? What if she became pregnant? She had no intention of having kids so young. On the same week she lost her virginity, she opened a new bank account, transferring precisely enough money to cover an abortion into it. Even if the worst came to the worst, she’d be okay.

Linda, who is now 74, never did need an abortion. She suffered a couple of miscarriages in her life and went on to have two children, but it was always important she had that money. Every time the price went up, she upped the money in that account, too.

She remembers her early days as a feminist activist in Liverpool being characterised by a secrecy and awkwardness around sex. One morning, she walked into her doctor’s surgery asking for the morning after pill. “But why do you need it?” the receptionist asked. “Because I had sex last night and the condom broke!” she shouted. The whole waiting room went quiet.

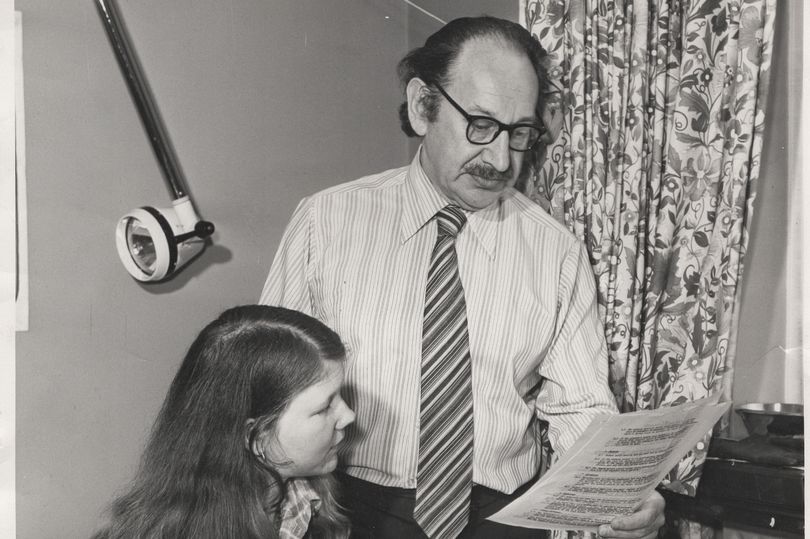

“Do something about that receptionist,” she muttered when she sat down across from her doctor, Katy Gardner. As well as her GP, Katy was a close friend and a fellow feminist activist. Katy is best known for being one of the first doctors to work in Princes Park Health Centre in Toxteth, the medical practice known for its health and wellbeing initiatives that supported the L8 community. Both Katy and Linda felt passionately about the availability of safe abortion being a political issue, but in a majority Catholic city with a political establishment that was vehemently anti-abortion, they often felt their views were overshadowed.

Linda and Katy’s lives coincided with a strange period in Liverpool’s history. The academic Dr Deirdre Duffy, a reader in critical social policy at Manchester Metropolitan University, spent years researching “abortion trails”. These were the routes used by women from Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland to access abortion in countries with more liberal abortion laws. Professor Lindsey Earner-Byrne, a professor of Irish Gender History at University College Cork, writes that Liverpool as a destination for those seeking adoption services can be traced back as far as the 19th century. Duffy’s research found that after the 1967 Act, which legalised abortion under certain grounds in the UK, things started to shift, particularly in Liverpool.

By the 1970s, Liverpool was the primary place for Irish women to seek out abortions they couldn’t get at home. They were often alone, travelling in secret, a false story told to their families and employers so no one would find out. Liverpool is thought to have been the most appealing partly because of its proximity to Ireland: girls could travel to Liverpool in the morning and be home the following evening. Because they were travelling illegally, getting an abortion was something they had to do quickly and quietly to reduce risk of anyone finding out and reporting them. Liverpool made sense. The ferry across the Irish sea was much cheaper than flying — it’s never been proven, but it’s thought Liverpool was a common destination for the most financially precarious women.

‘Why should they be made to suffer?’

Linda and Katy had started to notice the women arriving. No one quite remembers how the Liverpool Abortion Support Service (LASS) began. One woman claimed it started on a ferry, another said it was in a meeting. But it was Linda who sacrificed her abortion account to fund the Liverpool women’s reproductive rights campaign, which eventually culminated in the creation of LASS. She stopped having sex entirely for a year, not wanting to risk needing an abortion and not being able to pay for one.

They wanted to support the Irish women who had to travel to Liverpool to have an abortion. The premise was simple, or at least, it was at the start. An official rota was organised, where volunteers would sit by the phone waiting to be contacted by a few friendly doctors in Belfast and Dublin who were aware of the abortion services in Liverpool and could subtly tell patients about it if that’s what they needed. Then, they would organise these women’s appointments with a family planning doctor at the local abortion clinic, who would book them a counselling session and an initial examination.

Once everything was booked in, all they had to do was wait for them to arrive. A volunteer would stand at the docks when the ferry arrived, holding up a sign with their name on it. It would be early morning, that strange light when the Mersey looks very blue, and the next ferry wouldn’t depart until the following evening. Then, they would walk the women to their homes, where they had a spare room for them to sleep in overnight, and where the women would have someone to talk to if they felt lonely. Three doctors — Lis Davidson, Katy Gardner and the late Sheila Abdullah — were on call if the women suffered the heavy bleeding that can be a (rare) consequence of an abortion or needed any urgent medical help.

Why did the LASS volunteers feel such an affinity and sense of duty to these women coming over? One explanation lies in their politics. “These girls were scraping together from the bottom of the barrel to pay,” says Katy, who describes herself as a socialist feminist. “And really, why should they be made to suffer? And why should they have to pay?”

Another explanation might be found in their pasts. No one spoke to Linda about sex when she was growing up, and she often felt lonely as a teenager, having moved secondary schools four times in seven years. She said this made her more independent, but it also made her indignant: why this secrecy and strangeness about sex? Why did she have to teach herself? Liverpool, in contrast to her childhood, was a hotspot for kindness and community. She wanted to give back.

Two dozen women signed up to the rota hoping to help, but they realised they weren’t helping nearly as many women as they expected. One early statistic about the demand in Liverpool, which has no timescale but can be found in a selection of archives held in Liverpool Central Library dated between 1970 and 1985, found that 698 women came from Northern Ireland one year — out of these, 621 of those women used BPAS in Liverpool

Kathleen McKeating, a former social worker and LASS activist, remembers the number of women that LASS helped being significantly lower: she hazards a guess at around 14 women a year. In the early days, they would have two women on the rota each week. After noticing the demand wasn’t really there, this was slimmed down to just one.

Kathleen is now 75, with arms covered in freckles and wearing dangly red earrings. She remembers having “generally mundane” conversations with the girls she invited into her home. There would be endless cups of tea and small talk, but it was rare that they would want to tell her much about their situations. “It was about keeping things as normal as possible,” she adds. Despite this strange emotional distance between her and the girls she saw, she found herself worrying about them, and whether they made the journey back home safely. The ferry took between 10 and 12 hours, and the girls were often alone. There was also the fear of the women they were unable to help, who were in a strange city and didn’t know how to navigate their way to the abortion clinic. What happened to those that they couldn’t help? And was it truly possible to make this traumatic event a little more tolerable, a little more bearable, when they came from different worlds entirely?

‘The fewer people knew about our little secret, the better’

I find Carol in a blog post she wrote for Both Lives Matter, the Northern Ireland organisation that advocates for the life of the mother and the unborn child. Carol had an abortion when she was 13, taking the ferry over to Liverpool with her mother, banned from ever speaking to anyone about it or mentioning it to her parents again. Despite having had an abortion, Carol is vocal about the downsides of the procedure. She wants people to know that the experience “can be very, deeply damaging to women and men.”

“I am happy to talk to anyone who will listen to my story,” she wrote. “I find myself having deep conversations about abortion with people I hardly know — I have a story to tell and because I know it is the truth, I want to tell it.”

I ask Dawn McAvoy, the evangelist and co-founder of Both Lives Matter, if she can put me in touch with Carol: I want to know how this lonely journey to Liverpool really felt for women. She readily agrees

Carol believes in the sanctity of life, but she doesn’t align herself with the pro life movement. One day, she was in Belfast and saw a group of organisers huddled around a table, which was covered in photographs of aborted baby parts: small limbs, blood and tissue. “It pushed me further away,” she says. “I didn’t want to gravitate over to those people and say, ‘Oh, I had an abortion’. It hurt me, it deeply traumatised me.” For the purpose of this story, her real name has been withheld to protect her identity — she knows her views might be challenged and appear like a political statement, but she sees her beliefs as an act of love. When she went through a healing programme at her local church designed for those who have gone through abortion, she got to give her unborn baby a name: she named him Michael, and still thinks about what he might have been like from time to time.

It was the early 1970s when she met the man who would take her virginity. Her upbringing had been very permissive: she was allowed to stay out late at pubs and discos. They were out one night and they caught each other’s eye. She was 13, he was somewhere between 18 and 20. “I thought he was really nice,” she remembers.

For their first date, they went to his house. She was unsure of what they were doing and was unable describe the effect it had on her at the time, but she knows now that it was rape. After he was done, he offered to walk her home. He said he’d be in touch, but he never was.

A few weeks later, Carol started feeling unwell with a stomach flu-like illness. She spent the mornings throwing up and couldn’t concentrate at school. Her parents took her to hospital, where she took tests for everything from stomach cancer to rare terminal illnesses. One night, her mum asked her: “Is there any way you could be pregnant?”

“I remember vividly, sitting at the top of the stairs rocking back and forth, and then the penny dropped,” she says.

Everything had to be handled as discreetly as possible. This was her parents' idea: they were a religious family, pillars of the local community, and they didn’t want the shame of their daughter's unplanned pregnancy sweeping through the neighbourhood. Nor did they want to take the man to court — that would only make things worse.

She took the boat to Liverpool a few days later. Driving to the ferry terminal, she remembers her dad calling her “all sorts of names” and knowing she still didn’t know what was going on. When her and her mother got on the boat, barely speaking to each other, she walked into the bathroom for a moment alone, and she held her tummy.

The experience itself was a blur. What she does remember clearly is the conversation she had with a nurse, who explained to her in graphic detail what was about to happen. This felt cruel, Carol says, but she now realises the nurse was the only person who was honest with her.

When Carol got home, it was never mentioned again. She returned to school the next day. Where she had once been a brilliant student, her grades started to go down. Her behaviour became more erratic. The doctors prescribed her a low dosage of Valium, which made her feel numb and meant she didn’t have to think too hard about anything. She went off it, finally, when she was 16, having had enough of taking pills every day, and eventually built a successful career. She tried to put the past behind her.

From Carol’s perspective, the idea of staying with someone in Liverpool for support and company would have felt strange and false. The home of a stranger, while possibly an antidote to some of the women’s isolation, wasn’t something that seemed to appeal to her when I voiced it in our interview. “I don’t think my mother could have faced that,” she told me later over text. “I think I wouldn’t have wanted that, either. My mother wanted to keep it well hidden and the fewer people knew about our little secret the better.”

‘We hadn’t thought it through’

This need for secrecy and desire for autonomy was something LASS started to suspect after their first year. In Liverpool Central Library, I sift through the archives to look for suggestions about the kinds of women they helped — what lives did they lead, and where did they come from? But the information is scant. Three pages ripped out of a diary give some detail, but there’s a strong impression that the activists and the women had a distant relationship. While the activists were doubtless warm and supportive, it’s hard to imagine how it could be otherwise, given the intensity of what the women staying with them were going through.

“Woman aged 36 with six children between 5 and sixteen. Marital problems — husband kept ‘going off’. Hired on a family farm in the west of ireland. No close friends or family support. Husband did not know of the pregnancy. She had been accompanied by a friend, aged 21, a daughter of an acquaintance of hers. She however did not give much support while the woman was here. We tried to contact her to get her to stay at our house but she had gone out for the evening.”

“She was 18 — from a small town and had been ‘courting’ for a few years. No contraceptives. They were both employed. Problems arose over cover stories with families and the boyfriend’s employers. They thought he would only be away overnight. (her employer had arranged the bpas appointment).”

“The woman was apprehensive about the whole situation. She had enough of pregnancies and 4 miscarriages and felt the relationship she had with her husband needed sorting out.”

“They were very private and secret,” Lis, one of the family planning doctors who worked at Liverpool’s first abortion clinic, remembers. Her role was to offer counselling and initial support to women seeking an abortion, and occasionally do medical examinations or scans to determine how far along they were in their pregnancy. Some seemed wary to reveal too much about themselves — because, she suspects, they could be found out to have done something illegal when they returned home. Kathleen remembers receiving a postcard from a girl to let them know she was happy and had returned to a normal life. But otherwise, they never heard from anyone else again.

In 1980, LASS hosted a talk at a socialist feminist conference to ask the question: should we be organising a support network for women coming over to England for abortions? The support they gave to the girls was handled with care and sympathy, but they had underestimated the cultural and religious divide. Fundamentally, they didn’t understand how the women felt, or the fear some of them held about disappointing their families or whether God would forgive them. “We have since had three larger meetings and it has become apparent that we hadn’t thought through the political implications,” reads a letter from the archives, dated 1980. “It soon became obvious that we’d had insufficient discussion of the political context in which the network would be functioning.”

The demand for abortion services in Liverpool started to decline, and by 1985, the group stopped organising altogether.

During this time, Lis lived mostly in Dublin, working at the first Well Woman Clinic after the 1983 referendum which recognised the equal right of the life of the unborn child and the mother.

Sometimes she would come home to Liverpool on the ferry, the same ferry women would take home after their abortion. One time, she was on her way back to Dublin when a call blared from the tannoy asking for a doctor. She remembered the girls who used to discharge themselves early to take the boat home. Then she started to run.

She asked a crew member for medical equipment, but there were no supplies. On a ferry that took 10-12 hours, and a slight risk of bleeding after an abortion, this could be disastrous.

Lis made it to the scene, still thinking of those girls. In front of her was a young man who thought he was having a heart attack. She checked him over, took his pulse. It was a false alarm — everyone walked away unscathed and everything was fine. But it didn’t stop her asking herself: what if it wasn’t?

Comments

Latest

Between Labour, Reform and Jeremy Corbyn, what does Liverpool’s electoral future look like?

Pete Burns wasn’t nice, kind, or fair. But he was unforgettable

Can we revive Liverpool’s high streets?

Ghosts, gangsters and giving Liscard a chance

Irish women struggled to get an abortion at home. Could a group of Liverpool feminists be the answer?

‘Why should they have to suffer?’