In 1984, schooners and swooners flooded Liverpool

Ahoy sailor! Tall men, taller ships and a night to remember

So the pizza I was carrying slid right off the plate onto the floor and the restaurant manager was screaming at me and telling me how incompetent I was and I felt this enormous shrug move through me. Fuck it, I thought, relinquishing my notebook, my pen. I didn't want to work here anymore anyway.

You'd have felt the same way if you were 20 years old, had three other part-time jobs, were long since sick of your hair smelling of hot cheese...and had, for the past two hours, been flirting with a guy who looked like Dynasty's Prince Michael of Moldavia, who was on a mission to convince you that sharing a pizza with him was far preferable to serving him one.

1984 had been a weird year, anyway. The local news in Liverpool had been dominated, for months, by Liverpool FC winning 'the treble', and Scott's Bakery in Netherton being closed down, and the Cavern Club on Mathew Street reopening.

None of it meant anything to me; my world revolved around post-work nights out at the State Ballroom and the occasional mid-morning breakfast in Sayers on Bold Street, only stepping out of my familiar bubble for the odd coach trip to Flamingo's in Blackpool, or a £9 return train ticket to London to visit my dad. Back in July, there'd been an earthquake in Wales and the ripples had cracked the tarmac outside my flat on Percy Street. Part of me wished that it had shaken the whole of Liverpool out of its stupor and into another, less static world. But then, all at once, I got my wish when the Tall Ships Race berthed in the recently revamped port for four days in August.

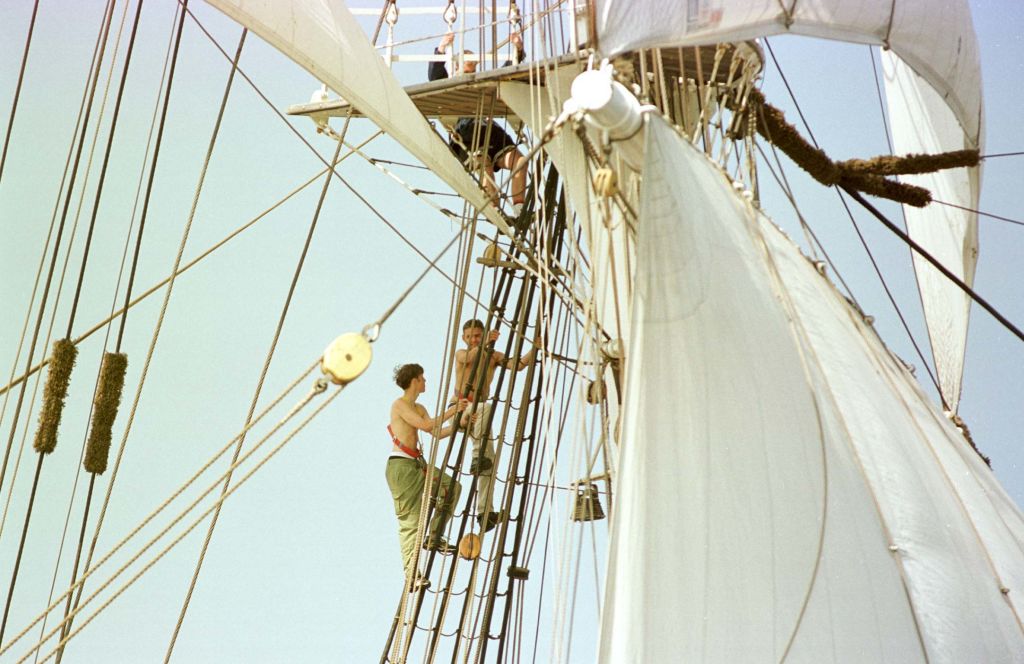

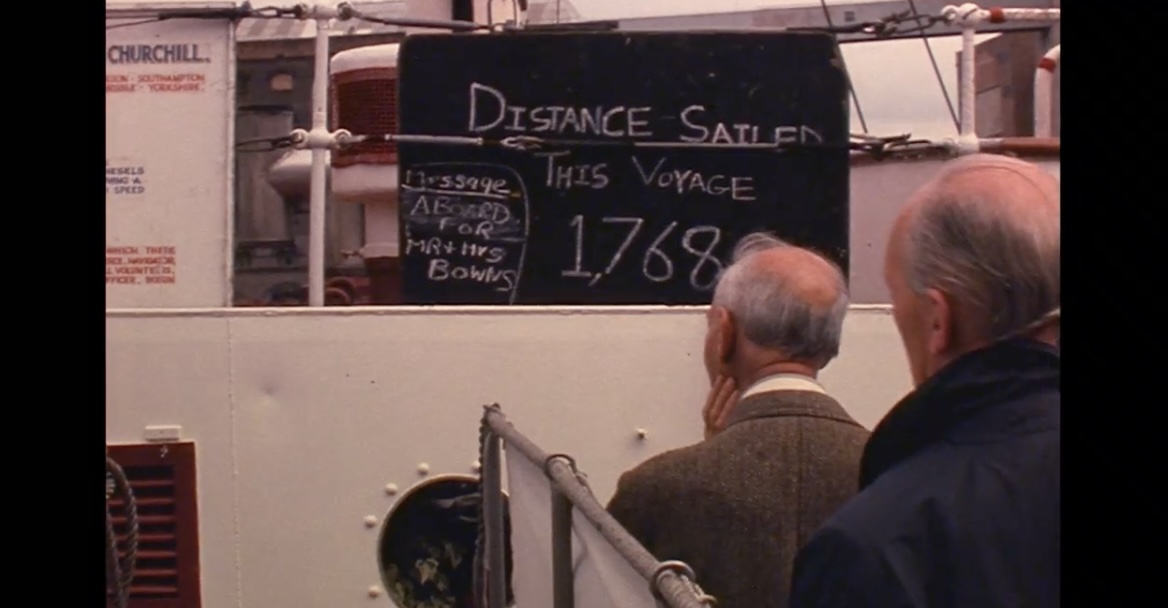

I'd never heard of the Tall Ships Race. Why — and how? — would I have done? I know now that it happens every year across Europe, involving hundreds of ships and their crews racing for hundreds of nautical miles.

The 1984 Tall Ships Race was scheduled to visit Liverpool for three glorious days to coincide with the International Garden Festival, which again, meant nothing to me; I mean, why make a festival out of a distraction as dull as gardens? But anyway, more than 60 vessels from Europe and North America floated in on the tides of optimism that surrounded the Merseyside Development Corporation's regeneration of Liverpool's dilapidated south docks and over a million people with, apparently, nothing better to do flocked into the city to witness the spectacle.

Despite my low mood that year, even I had to acknowledge that the city centre was buzzing. The tip jars on the tables in the Hardman Street pizza restaurant where I worked was overflowing with generosity from tourists from Northampton or Dudley or Ida-bloody-ho, despite the fact that their food was slung at them so fast during peak times that it almost skimmed the piles of Liverpool tourist tat (LFC mugs; plastic yellow submarines; 'Scouse Dialect' tea towels) strewn across the table. They needn’t have bothered. Despite their magnanimity, they weren't the kind of tourists I was interested in.

Pressed into sharp uniforms and reeking of exotic cologne, the Tall Ships' sailors looked like Hollywood movie stars. All the more when set against the backdrop of the weedy boys in imitation leather jackets we were used to, who now seethed as the new kids on the block turned heads. Those new arrivals had another advantage over the locals too, as thousands of Liverpool girls took the offer of free entry from hundreds of nightclubs packed with 'Liverpool Welcomes Visitors' — and hundreds of non-sailor boys were refused entry to the same clubs. The girls glammed up like never before in readiness for a close encounter with somebody other than unemployed Billy from down the road or Andy the builder from Birkenhead. A speedily-scrawled sign behind the lingerie counter in Blacklers' department store informed shoppers “we are temporarily out of satin camisole sets”.

On their Liverpool pitstop, the sailors had cash and charm to spend freely, regardless of their own domestic circumstances at home, thousands of miles away. Much as how the influx of American GIs swept British women off their feet decades before, the Tall Ships sailors brought holiday romance opportunities to our very own doorsteps. Back underground, the city's gay bars and clubs reported a roaring trade in all senses of the words, too; as the wearied one-liner went, “you can't move in the Mazzie/Sadie's/The Lisbon tonight — the bar's swimming in seamen”. Hello, sailor!

I usually only worked as the dishwasher in the kitchen; they didn't let me serve out front because I wasn't “neat” enough. But when the ships came in, so did mine, and I was temporarily promoted to waitress. Two hours into my short-lived promotion, it gave me a thrill to tell my manager where to go and take to a table as a customer and have one of the snooty permanent waitresses serve me, knowing that somebody else who wasn't me would have to wash my dishes when I'd finished, and knowing for sure that they'd all be amazed to see how quickly I could transform myself from staff to customer when not swabbing away leftovers in the sweaty kitchen.

My sailor said that his name was José: “Ho-SAY”. I sat at the end of his table of four (four sailors! I was suddenly sitting with four sailors! If it hadn’t been so hot outside, I could have sworn it was Christmas) and ordered a Quattro Stagioni because I knew how much the chef hated making them, and the Pernod, cider and blackcurrant that I was suddenly desperately in need of. I was fascinated by their accents; slightly singsong, with the 'sh' sound on their s's making it feel like they were whispering, no matter the volume they spoke at. “Are you speaking Spanish?” I asked. “No, we are speaking our language, and therefore we are being rude to you, as you are speaking English”.

I coloured a little.

“When we leave here, we go walking, yes?” José whispered. Oh, yes please...

After I'd finished my pizza, my former manager brought a complimentary bottle of Asti Spumante over to our table. She said she was sorry for snapping at me, and she needed me to come back to work the next day. I knew that I'd never go back.

We took the Asti with us and I drank it from the bottle as we walked down the hill towards the clubs, bars and people of Bold Street. But, “no, not down there,” he said; “let's go down there, to the Chinatown. We have one at home, in Bogotá. I would like to see yours.”

And so we took a left along Berry Street towards Nelson Street, navigating our way through and past the taxi rank and the pubs packed with revellers until we reached the streets of Chinatown, its pavements lit by neon from restaurant windows, the cafes and launderettes that punctuated the route packed with mahjong players and billows of steam from huge tea urns. This was decades before multiple regeneration schemes had scrubbed the 'real' Chinatown away, long before a dazzling arch threw a spotlight on highways and byways ripe for an influx of 'modern Chinese' restaurants and hip 'Street Food and Cocktail' emporiums.

I explained to José that I was born and grew up just a stone's throw away from where we walked, long before the Chinese takeaway was convenient, let alone ubiquitous. If we wanted Chinese food 'to go', we'd have to take our own bowls and containers to the restaurant with us, and sit on rickety little ex-restaurant chairs adjacent to a scarily hot kitchen while chefs (I assume) laughed at our Very British Order of Chow Mein, Sweet and Sour Vegetables and Special Fried Rice (“can we have chips too?” “We don’t do chips! This is Chinatown!”).

I told him how I'd gaze – partly in horror, partly in yearning-to-try fascination – at the whole, fluorescent-red roast ducks that hung over the wok station, and he said that he wouldn't dare try one either. And then... “I don't have happy stories from my childhood to share,” he said; “it wasn't until I became sailing that I saw happy.”

I was disappointed, for him and for me. I wanted him to tell me tales of childhood picnics on beaches, and carnivals, and a close, happy family life. “There is kidnapping and drugs all over where I live,” he said. “Colombia is poor and dangerous. You never visit, it is not good.” Blimey. All over Liverpool, sailors were partying — and I'd been stuck with the grim one who needed therapy. So...

“I'm starving again,” I said, in an effort to lift the mood; “fancy a spring roll?”

“I've never walked along a street with a woman who is eating food,” he said, starting to smile again.

“We'll find somewhere to sit down, then,” I reply.

“You know everything about everything,” he said.

I wished I did.

José bought four massive steaming spring rolls from a restaurant with a takeaway hatch in the corner of the front window and we meandered up Upper Duke Street, our conversation picking up the pace faster than we dawdled along, José telling me all about galley grub on the ship, and regular uniform roll-calls, and what the stars look like from the middle of the Caribbean Sea in the middle of the night. That's more like it, sailor boy!

By the time we were halfway up the hill our spring rolls were cool enough to eat so we sat down on a wall outside the Liverpool Institute and ate gazing at the huge moon that hung behind the cathedral's massive tower. I told José that the cathedral was still being built when I was born, in Gambier Terrace. He stared up at the tower, in total disbelief; “everywhere in this city there are surprises,” he said. “You are a surprise.” What on earth did that mean?

When we'd finished eating, we walked up to the corner of Hope Street and Canning Street at the top of the hill where we could see right down the huge spacious vistas of the city's southern edge and the misty river beyond.

“I've never had a night like this, ever in my life!” said José; “a night where you just don’t know where you’re going, or what you want to do next.”

I had. I'd had loads. They just didn't usually involve boys — and certainly never sailors.

“But I do not want to see you again, ever,” he said serenely, entirely out of the blue. I was gobsmacked. He knew we were almost on my doorstep, but there had been no ambiguity, no discussion, about what would happen next — well, none that had been said out loud, anyway.

“I wanted to meet a less complicated woman tonight,” he explained. “I have my own complications back home. But I thank you most sincerely, and I have had a lovely time. So goodnight, yes?”

“You could've just said that you're married, if that's what you mean,” I said. “And anyway, I wasn't going to invite a bloody stranger back to mine, anyway. Okay?” “Ah, okay,” he said. “I did not know we were still strangers. But I do know that you are more complicated than me.”

And that was that. He did a funny little salute thing and then turned on his polished, clicky heels before marching away double-quick, without turning to look back. His parting shot was either a compliment or a lucky escape, but at the time, it was devastating to have been rebuffed so sharply.

I made my own way home and watched from the kitchen window of my Percy Street flat as taxis delivered groups of sailors to and from an encounter with the local ‘ladies of the night’ whose lives, for sure, were far more complicated than mine.

There's still plenty of myth and folklore surrounding the Tall Ships' sailors and the legacy they left behind in Liverpool, several of those stories implying a massive rise in the birthrate nine months after the sailors sailed off, many more involving women who had left their husbands for a 'tall, handsome stranger' only to return home three days later. Most of those sailors weren't, of course, the ship's captains, or the princes, or the millionaires that they said they were — and at least my brief encounter didn't spin me any of those yarns.

Over the next couple of days, I told a couple of friends about my night out with José. But the tale felt as inconclusive as the experience turned out to be.

“So he was married, then?” I didn't know. “So you wanted him to come back to yours, but he didn't fancy you?” I didn't know. “So you're going to get your job back?” I didn't try.

All I knew was that José showed me that choices and adventures can roll in on the tides when you least expect them; it's up to us whether we dive in or sit out the fun on the shore.

I was never as complicated as José thought I was. Imagine if he’d guessed? I was just a girl who was sick and tired of working in a pizza restaurant and he was a great way out. All the same — I can’t help but wonder where, how and who José is today.

Comments

Latest

The watcher of Hilbre Island

A blow for the Eldonians: ‘They rubber-stamped the very system they said was broken’

How Liverpool invented Christmas

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

In 1984, schooners and swooners flooded Liverpool

Ahoy sailor! Tall men, taller ships and a night to remember