How I fell out of love with football

As Everton hunts for its knight in shining armour, David Lloyd recounts a personal loss of faith

I’m lying on the trolley in the endoscopy suite, readying myself for my colonoscopy. Baggy shorts on. Flies to the rear.

“Firstly I will introduce my finger to your back passage,” my assailant purrs, doing a passable OJ Simpson with a pair of latex gloves.

Pleasantries exchanged, he drops the most important pre-procedure question of all.

“Are you a red or a blue?” he asks, glistening, fun-sized camera poised.

“I… I’m a blue,” I splutter, blissed out on a heady mix of oxygen and fentanyl (very moreish, I must admit).

“Good. I’ll be gentle then,” he says.

As his tiny mascot enters the tunnel, he asks: “Did you see that Beto clash? Nasty, wasn’t it?”

Suddenly, I am laid bare. I have absolutely no idea what he’s talking about. Because I’m not really blue. Oh sure, I was once. And once a blue and all that.

My cover is blown. It usually is. I don’t know why I persist with this charade. The camera does a sharp handbrake turn in my transverse colon and I scream for forgiveness like the worthless, football-denying heathen I truly am.

Because the fact is, I don’t believe in football. At least not anymore. Sure, there are places of worship. There is the clergy, the liturgy, the soul-soothing accoutrements and trappings of ritual and practice. The Stone Island and Lacoste subculture, the podcasts and jarg replica kits. The pundits and the bants, and the slow, inexorable climb up the waiting list for a season ticket. The England flags on the Ubers. But there is an emptiness at the heart of this religion. Whisper it in this city, though, and you might as well brick yourself into a priest hole.

But despite all of this, the news of late, from the condemned boardroom at Goodison, of the club’s desperate and unseemly hunt for their own saviours, has saddened me more than I’d have thought.

I remember my first match. I was happily painting some trackside bushes on my Hornby Night Mail train layout when my dad came into my bedroom to ask if I fancied coming (turns out his mate had a hangover, so I was his super sub.)

I remember the smell of horse shit and hotdogs. The ragged, fractious mob. The misty autumn afternoon thick with testosterone and filigreed with wisps of Benson and Hedges.

Football, it turned out, involved a melee of men chasing a ball around a lovely lawn for what seemed like three weeks. Occasionally, this would make the crowd erupt from their seats and bellow into the maw of the stadium. At one point, my dad showered a volley of sweary words into the biting Walton air. I’d never heard my dad swear before.

What power did these men hold over Dad? Why did they make him so angry? So…scary? If he didn’t like it, why didn’t he just stay home and help me sculpt my sidings on my model railway?

A sinking feeling crept over me: football wasn’t as exciting as The Pink Panther cartoons I was missing. Clearly, I did not have its secret decoder ring. I spent most of the match wondering how I could write the advertising hoardings better, and which ones needed a punchier colour palate.

And this was in Everton’s early 80s glory years, when trophies came thick and fast. Well… trophies came.

Despite my initial misgivings, before too long, Everton pendants and pictures of Graeme Sharp and Andy Gray were muscling in next to posters of Madness and Kate Bush on my bedroom walls. I was a fan. I was a blue. It mattered. The whole random, messy, zero-sum nonsense triggered some hitherto unrealised need in me. I wanted to please my Dad, I wanted to fit in. I needed to hitch my still-shaping personality to a tribe, and football was an easier choice than quilting. It came knocking on my door like an eager Latter Day Saint, and I let it in.

I suppose, back then, I also wanted to see my city, my people, triumph. My impressionable pre-pubescent self must have been alive to the teroir of the team. I probably didn’t tussle with the concept of teroir too much then, but I knew that, if I snuck into the changing room at half time it would smell of Jacobs Cream Crackers and Higson’s mild. In the same way Anfield’s changing rooms now must smell of Tom Ford Noir with a base note of Lamborghini Urus leather trim.

Over time, my tribal allegiances waned. I still felt, should anyone need to ask, that — yes, I was still blue. Please don’t beat me up. But whether I actually supported football or not I wasn’t quite so sure of. Try as I might, this didn’t feel like my tribe at all.

I remember my Dad taking me to Wembley in 84 to see the team beat Watford in the FA final. Everton fans next to us unfurled a huge banner proclaiming: Everton are like Elton John. They come from behind — and the entire terrace cheering. Elton, Watford’s then-Chairman, probably found it as hilarious as I did.

They don’t unfurl banners like that these days. There’s no need to, because there are no gay Premier League players. There never has been. There’s only one gay player in the entire English Football League. One in over 1,000 players, which is a real stroke of luck because, when it comes to stuff like equality, football solidified its opinion on such things somewhere around 1938, and it sees no reason to change any time soon.

The only other explanations for the phenomena are laughable. Should a footballer come out, they suggest, sponsorship deals would suffer, agents would fret over dwindling career options, changing room dynamics could ostracise the player, and homophobic chants would return to the terraces.

This is 2024. Those days are over, right? The FA has Pride PR campaigns now. But for every campaign, there’s a Qatar. And for every LFC player who’s a vocal ally of the LGBT community, there’s a handsome paycheck waiting in Saudi Arabia to turn their heads and nudge their moral compass.

My glory days, like Everton’s, didn’t last long. For me, football evolved into something else, something darker, less welcoming. It wasn’t just about the racism, the homophobia and the casual violence; as time passed there was another implanted cell which was silently mutating the game beyond all recognition — at least for me. Money.

When you accept that football’s a game where the deepest pockets take home the trophy it follows that you sidle up to murderous regimes, sleep with fraudsters, and entertain embezzlers. These are the skillsets any Premier League team needs more than nimble-footed star strikers and a safe pair of hands at the back.

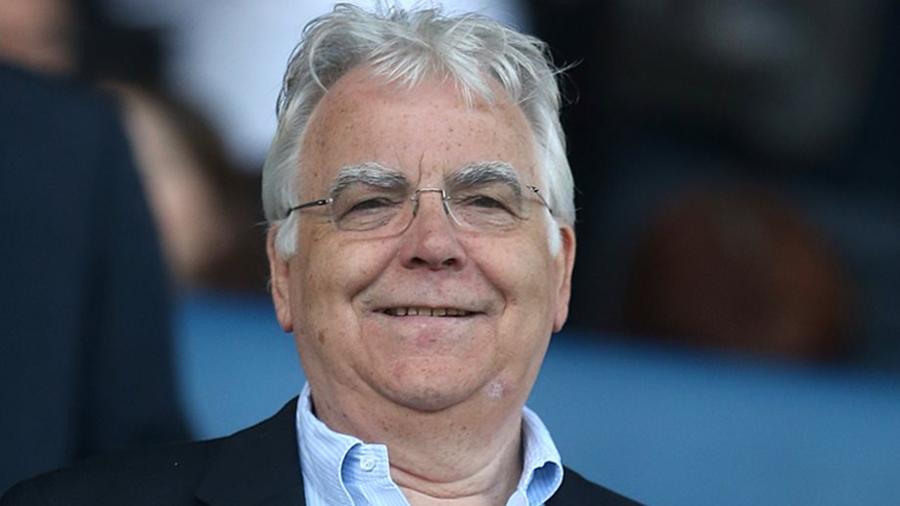

Throughout the unseemly chapter of Everton fans baying for Bill Kenwright’s blood, the only crimes he was accused of were of lifelong loyalty and, sure, a lack of investment and unwillingness to play the game. The new game. But the subtext was also anger at him not having as much cash as a Putin-supporting oligarch. So he had to go.

Tenacious though his grip was, I’m not sure he ever knowingly sanctioned the assassination of a dissident. And yet Kenwright’s beloved club was reportedly mulling over a cash injection from the Saudi royal family, whose heir apparent is Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. If you know your history, you’ll know. Unlike Newcastle, Everton has opted, instead, to agree a deal in principle with AS Roma owner Dan Friedkin. Small mercies, I suppose.

But with previous front runners 777 accused of fraud, Saudi cash still hovering over the Premier League like Sonic’s gold rings, and Manchester City’s Sheikh Mansour’s alleged safe havens for sanction-fleeing Russians, the unseemly dash for cash has laid bare the game’s struggle to still hold the onto the rights to its heart and soul.

I was lucky. I got out. But I know what people, my friends included, say. I was only ever the Leah Remini to Scientology’s Tom Cruise. I wasn’t a true follower. How could I be? I was the second-to-last-lad left against the wall when the PE teacher’s glory boys were allowed to pick their teams. And now I’m a heretic — shouting into the winds, well aware that even writing this piece is as futile as handing out vaccines at a Piers Corbyn rally.

Fortunately, I now know that what was happening back then to my still-pliant synapsies was nothing more than my brain’s reward system needing a hit. It wasn’t about the dextrous ball skills and gamesmanship on display (although, with time, I did learn to appreciate Dunan Ferguson’s formidable aerial prowess, and the ferocious yet balletic tacking of Kevin Ratcliffe). No, my brain was being rewired with every trip to Goodison.

Neuroscientific studies at Oxford University show that these shared intense experiences of wins and losses with fellow fans become self-shaping, embedding the team's identity into the fan's own sense of self. It’s the reason why football fans who’ve never kicked a ball since a five-a-side knockabout in 96 still say ‘we’ played well on Saturday. Telling a fan that their loyalty may have less to do with history and pride and more with a cranked up ventral tegmental area and an amygdala on fire isn’t likely to win you many friends though.

This isn’t just about Everton. It’s about why I fell out of love with football. Which, for me, happened around the same time I think our teams fell out of love with our city. LFC failed to deliver on its promise of regenerating Anfield with its Stanley Park stadium complex. Not its finest hour, as many local residents would agree.

For me, football is the archetypal example of the ship of Theseus. When every plank, rivet and sail has been replaced, what are you fighting for anyway? Your city? Without wanting to venture too far into Farage territory, much as fans fought against the move to Kirby, saying how Everton couldn’t be taken out of the city, no-one really cared too much when the city was taken out of Everton. Or Liverpool.

Just as our cities became a screensaver backdrop of interchangeable high streets and identikit apartment blocks, so our teams became a moveable feast of players renting penthouse suites, and leasing Range Rover Sports all the while keeping their eyes on the bigger prize.

People say that football is a religion in this city. They’re right. The loyalty of football fans triggers the same reward systems in the brain as religion. Match or mass, the deal’s the same. They’re both artificial constructs tapping into an evolutionary need to polarise and choose our side: the ‘us vs. the enemy’ mentality rooted deep in our ancestral DNA.

Give us your loyalty, your devotion and your money. Give us your unwavering, unquestioning acquiescence. We’ll give you an intense emotional connection and sense of belonging. And, occasionally, in the case of Everton, we’ll show you a miracle now and then.

But I really do get it. The need for faith, for transcendence, runs deep, and it’s hard to tear yourself away from football’s sure and certain hopes. We all need escape routes. Tribes. Connection. And most football fans I know get this: they’re alive to the cognitive dissonance their support brings, keen to vent their anger at the same shortcomings that cost me my devotion. They’re embarrassed by the panderings of the FA to Sky or BT or anyone who comes a-courting, the dark arts of FIFA and the frustrations of the modern game, in much the same way as many decent Catholics stand against the sins of their church. But where do we go from here?

It’s hard to look at the game dispassionately, especially in this city. It’s like trying to unweave a rainbow. But when the scales fall from your eyes it’s blindingly obvious that your club, the club you swore allegiance to, is long gone. The only constant is the fans.

Today’s Premier League clubs are no more than a confection of licensing rights and sponsorship deals, an itinerant roll-call of agents and players, managers and CEOs halfway up, or halfway down their lucrative career trajectory. They’re hitched to a religion that practises the art of looking the other way when it comes to diversity, community and human rights. It has to. The FA is the way and the truth and the life.

Ultimately, though, it’s not the broadcasting revenue, the corporate packages or the merchandise that keeps the game alive, it’s the fans. And the longer they’re happy to sit silently in the dugout, the longer they’re happy to pay their indulgences to their church, the longer this game drags on into extra time.

My dad doesn’t go to the match any more. But he tunes into Radio Merseyside for every fixture, and knows the squad inside out. Over the years I’ve witnessed a million expressions in dad’s eyes as he tunes in. He rolls with the punches, the highs and the lows. He’s a blue, what else can he do? But when we talk of the 777 spectacle, the perilous finances and the news of dalliances with Saudi cash I catch something new. He looks forsaken.

So if Rishi drives up our road in his election battle bus this weekend, and asks me if I’m looking forward to ‘all the football this summer’, my answer is simple: I’ll be with the Welsh.

That’s after I tell him to fuck off out of our street. Because some tribal allegiances are more important than others.

Comments

Latest

Northern Powerhouse Rail is back on track. We think...

The clockmaker of Wavertree

One of Merseyside’s oldest sports clubs still plays every Saturday

Does Liverpool have a ketamine problem?

How I fell out of love with football

As Everton hunts for its knight in shining armour, David Lloyd recounts a personal loss of faith