Heroes for one day, every weekend: memories of a Liverpool New Romantic

High-gloss, coiffed memories of an underground scene

Life in the UK during the early 1980s wasn't pretty: the headlines were dominated by riots and spiralling unemployment figures, Margaret Thatcher headed up parliament, and both the AIDS pandemic and the Falklands War loomed in the background, waiting for their moments in the spotlight. But at 17, my world was dancing to a very different beat.

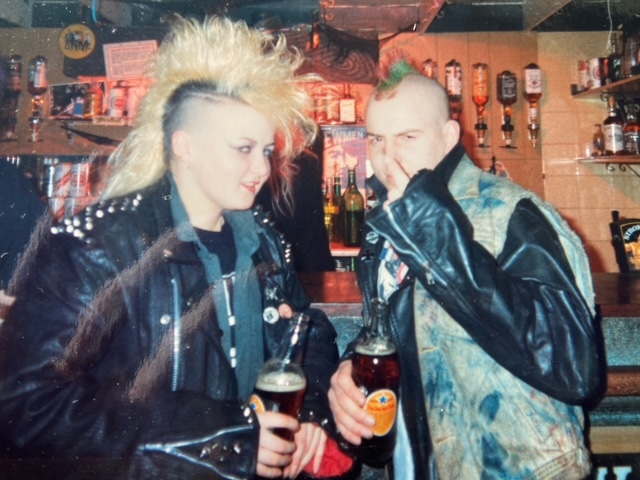

Brave new world influences that began as an underground subculture in late 1970s London were starting to subtly dominate Liverpool's tiniest alternative nightclubs, slowly but surely consigning the ideology of punk to the cultural dustbin. Glossy, pompous, and unafraid of flaunting pseudo-intellectual aspirations, this city’s post-New Romantic scene transformed a harsh landscape into a rebellion against everything that Thatcher's Britain stood for. It was 1982 and Liverpool felt like the centre of the universe.

The music: cold, hard, tinny synth-led bombast with lyrics that refused to be unpicked: “You are perfect, you are sheer, If you are a red-haired queer”. “Spilling up in silk and coffee lace, you hook me up a rendezvous at your place, your lipstick and your lip gloss seals my fate”.“ One man on a lonely platform, one case sitting by his side; two eyes staring cold and silent, shows fear as he turns to hide...” “The shrieking of nothing was killing it — Oh, Vienna!”

The Look: outfits that blended 1970s glam with Marie Antoinette flair, ball gowns, fans and a full face of slap, or 1930s red-carpet Hollywood with Blade Runner-inflected neo-noir, or charity shop wedding dresses with a BHS denim jacket. If you could dream it (and then, make it), you could be it.

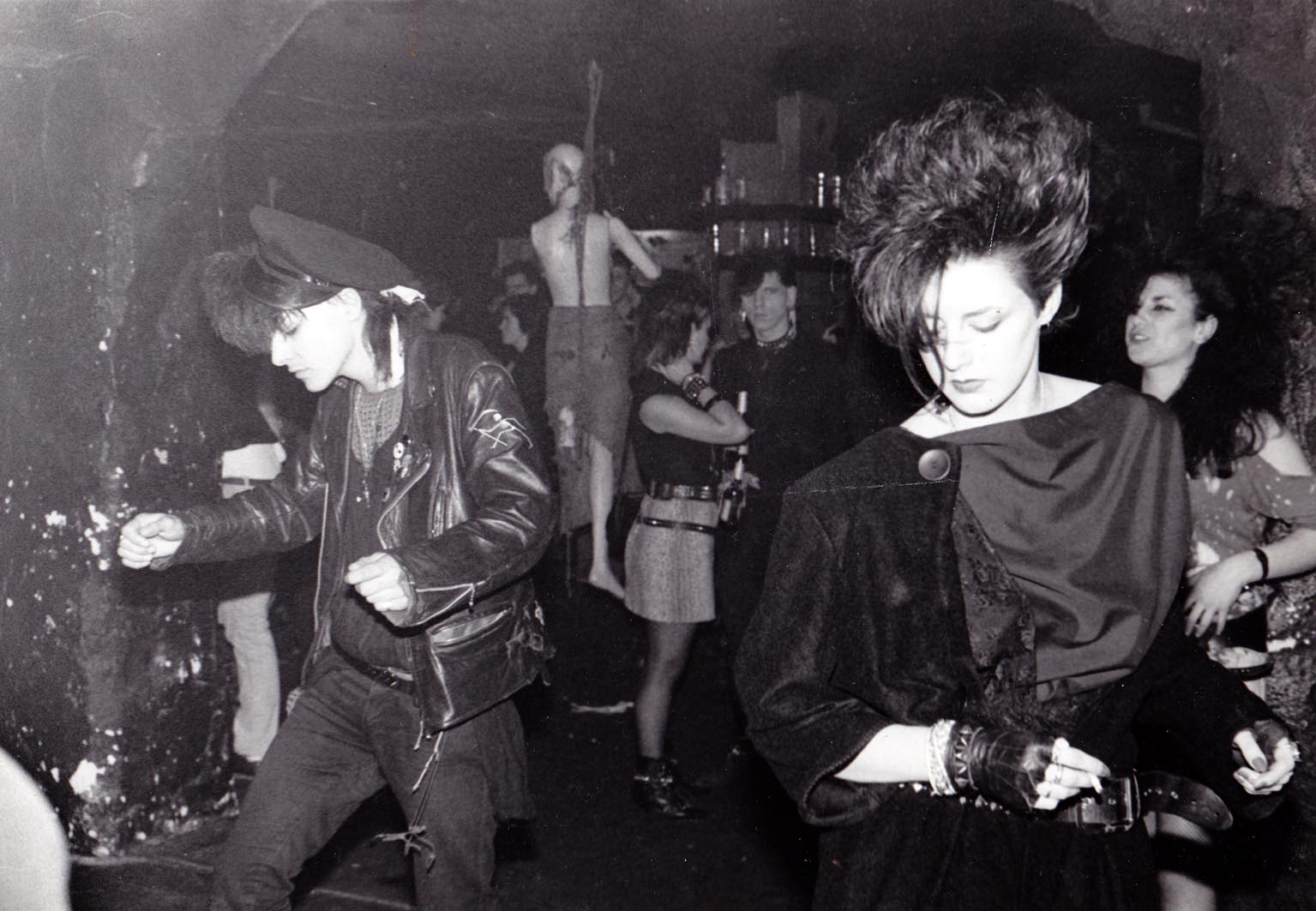

But the music and the look were nothing without the catwalks to see and be seen on: The State Ballroom on Dale Street. Yates's Wine Lodge on Great Charlotte Street, if you were brave enough; the Beehive at the bottom of Mount Pleasant if you weren't. But what could compete with Planet X?

Even entering the club was exciting: paying always-friendly Doreen on the door, trying not to stumble in my heels as I tottered downstairs...and into another world. A parallel reality where dance floor lights were bright, walls were black, and the people as wild or wallflower as they wanted or needed to be, with nobody to tell you that you looked wrong, or didn't fit in, or shouldn't be who you were.

As 'our' music started to creep into the UK charts — Kraftwerk's ice cool ‘Model’ outselling Shakin' Stevens rancid ‘Oh Julie’; Soft Cell's haunting ‘Torch’ battling with the brutish England World Cup Squad for supremacy — Planet X became a home from home for those who wanted somewhere to keep on keeping on in the style to which they'd become accustomed to in their own uniquely beautiful way.

Edward — pale, willowy, with beautifully-coiffed hair, one half platinum blonde, the other half brunette — worked in the canteen at the Liverpool Echo offices by day serving subsidised lunches to journalists who reported on the latest council estate murder, or plans for the new shopping mall development in town. Les worked in his dad's Garston garage where he kept his velvet drape jacket, purple beetle crushers and neon orange shirt carefully locked away in his locker, ready for changing into Superman phone box-style after he'd locked the forecourt up on a Saturday afternoon. Vincent the civil servant transformed on the long bus ride from St Helens to Liverpool city centre every weekend, carefully folding his work suit into the satchel into which he'd carefully packed his Victorian school ma'am's outfit complete with pinafore dress, white bonnet and....rouge, black fishnets and red patent leather stilettos.

In MacMillans and Planet X, Edward, Les, Vincent and all of us could be whoever we really wanted to be, away from the panic flashing in the eyes of families, employers and colleagues who didn't understand why being a canteen cook, or a car mechanic, or a civil servant, was the destination rather than a journey to somewhere — and something — else. It must have been hard if you lived at home during that time, being accused of being a gloomy goth, being told to “dress properly”, being told that early nights were the key to career success.

Which is why, I suppose, that those of us who'd forged their paths out of suburbia and into independent bedsit land away from their family homes laughed in the faces of all those who made the accusation that people who 'looked like us' were busy going nowhere, and doing nothing other than living for our post-sunset life. I mean, really! If we didn't work, how could we afford to live the way we chose to live?

In early 1980s Liverpool, the disturbing demi-monde who made the Daily Mail so angry didn't, apparently, have jobs — but we did. We weren't supposed to sign on at the same time, but we (or rather, many of us) did. We were constantly told — by politicians, parents, passers-by, bus drivers, and a whole load of other random people from whom we were totally, utterly disconnected — that we'd never make anything of ourselves. But in our own peculiar way, we did; after all, we were the ones regularly getting our photos in The Face or I-D Magazine every week — we were the ones making our own headlines.

I worked in the Pizza Pizza Pizza kitchen on Hardman Street most weeknights — a bustling pizzeria packed to the rafters. Some weekends, I'd be offered a stint on the cloakroom counter in MacMillans: a basement down a set of stairs off Concert Square with a dance floor in one corner supplemented by plenty of dark, smoochy corners to lounge around in and a ladies toilet that was always packed with gossipy boys and men in drag who were only too happy to share make-up tips. But my favourite job of all: behind the counter in Xtremes — a clothes shop in a basement around Matthew Street (Button Street, perhaps?) on selected Saturdays.

I was once paid with a crackling tartan frock which I wore that very night; I turned up for work looking like a fat Hilda Ogden and left looking like Elsie Tanner on her way to a wedding. By right, I should have been cowering on the edges of a city centre nightclub dance floor while thin girls who aspired to jobs on the till in TopShop wore thin clothes they'd bought that day in TopShop. But by whose rights, exactly? Not mine. If you've never danced to Soft Cell's version of ‘Tainted Love’ while actually believing that you had metamorphosed into Marc Almond, you haven't lived.

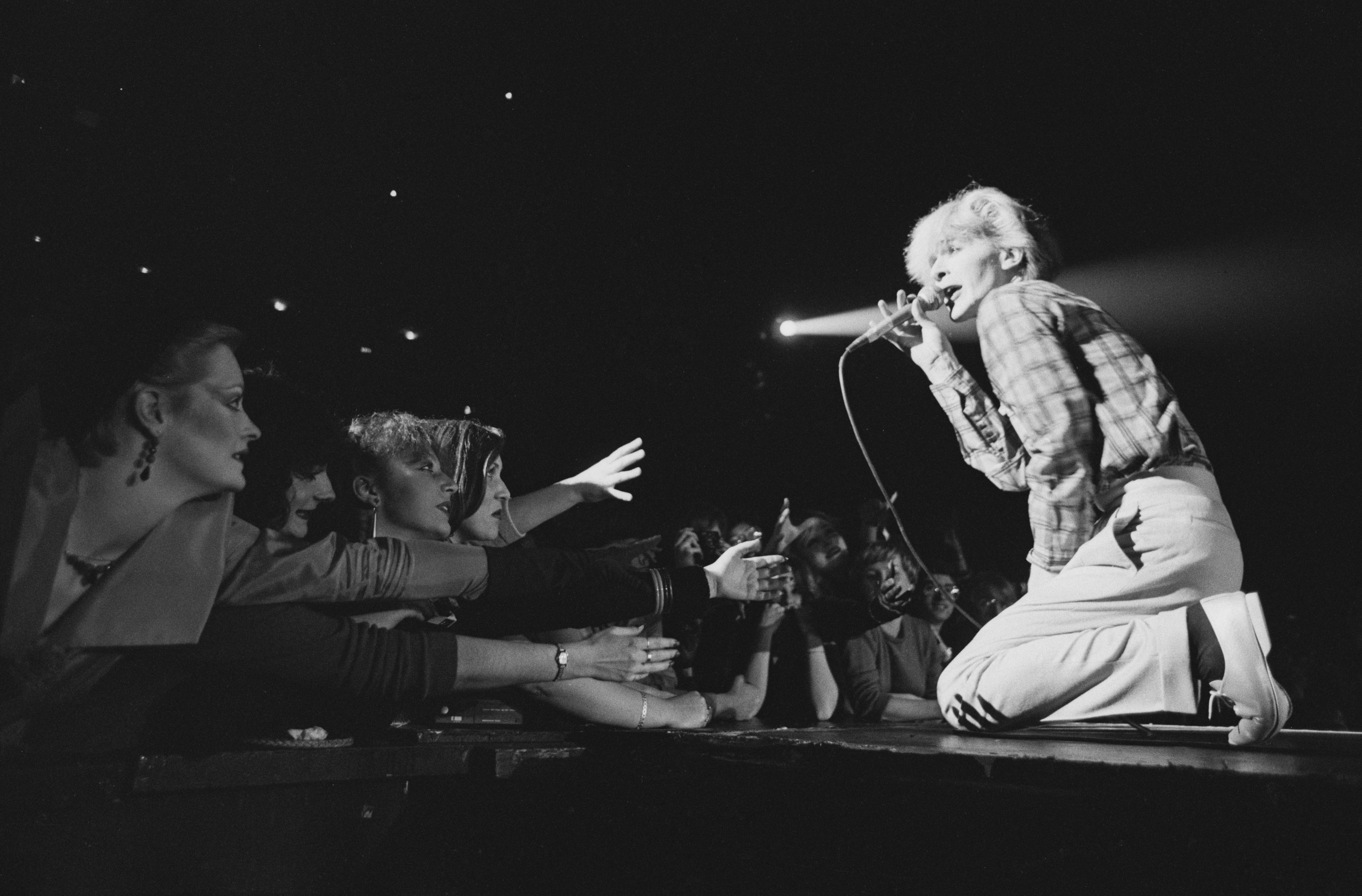

The best nights of all were punctuated by the anticipation of royal visits from our heroes. I’ll never forget a performance by the new wave band Japan at the Royal Court in 1981: in my shallow, fickle world, the gig was a fashion show rather than a concert, and I, of course, had to dress for the occasion. My best friend Colin — a fashion student in search of a muse — made me a beautifully-structured, tailored frock from fabric (“never, ever call it material, darling”) that had been out on the town many, many times before before, turning a tattered, frayed cocktail dress that he bought for pennies at a jumble sale into a one night only, startling creation complete with an ermine-trimmed wrap (it was easy, back in those days, to buy real fur to play with).

I bought a packet of 20 Sobranie Cocktail cigarettes to stuff into my black velvet evening bag especially for the occasion: a handmade selection that claimed to be formerly exclusively supplied to the court of the Russian Empire, each wrapped in cigarette paper of soft pastel tones. Well, if David fancied a fag after the gig, I couldn't offer him a Benson and Hedges, could I? And yes, I was intent on meeting Him after the gig – after Bowie, Japan’s lead singer David Sylvian was, after all, the ultimate hero for our times.

There I stood at the stage door, freezing and terrified in a frock that was already threatening to tear at the seams, being shoved around by roadies and laughed at by stags and hens making their way to the Penny Farthing pub just next door. And suddenly, there He was: dashing from stage door to tour bus, looking pale, and bored. And there we are, the people who were boring him, who had waited, waited, waited for this moment for so long.

Oh David, just look, look, look our way, my way, for just a second — just one second, that's all we need. But he doesn't. He just ducks and runs, his lipstick intact and his blusher too strong and his long blonde fringe in his eyes. He looks like an angel, covered in gold and purple glitter. We look like extras on the very, very far reaches of a 1950s film set, exhausted and overwhelmed in our tatty, ill-fitting costumes.

I was in love with David — I had few other choices; we didn't do romantic relationships except with our bedroom mirrors, and our unobtainable pop stars, and the friends we couldn't live without…and I had plenty of them. It always struck me as funny that the general perception of gay men back in the dark ages revolved around them being limp-wristed “effeminates”. If any of the men who used such terms so casually had walked into Jody's and asked if they only served poofs...let's just say I'm glad that never happened on one of the many evenings I sipped warm white wine at the bar there, dressed (by Colin, of course) in a female version of what the clones wore: plaid shirt, leather waistcoat, western bandana neckerchief, leather cap, black biker boots, denim ra-ra skirt, my ubiquitous fishnet tights and a bracelet made from handcuffs.

I may have been hissed at occasionally, and I once had my feet spat on by a huge 6'6” chunky hunk of a muscle Mary — a beefed-up Brando, egged on by a slightly less beefed-up Lee Van Cleef. But I was with my bouncers — my cowboys, my moustachioed, hi-energy Village People, with their bottles of poppers in their hands and their green/light blue/orange hankies hanging out of the back pockets of their 501s. When I met the Jody's boys, the strange little planet I inhabited tilted a little bit more towards the sun; I felt as though I had arrived, and would never leave.

They turned me — a girl with pudgy hips and stumpy legs and allergy rashes all over her arms — into someone else entirely: a woman who confidently faked a beauty spot just above her upper left lip; a women who had a selection of men on whose arms she could make entrances with; a woman who could dance to The Boys Town Gang's version of ‘Can't Take My Eyes Off You’, secure in the knowledge that the eyes of the people she cared about were on her — to me, that was romance in the truest, newest sense of the word.

I don't have to romanticise the ones we lost as the world turned and that iceberg eventually hit — they romanticised themselves, and continued to do so for many decades to come: many of the fashion designers, pop stars, writers, artists and musicians who frequented MacMillans, Planet X and Jody's live on in the work they managed to do in the small time they had to do it, and the dance floors of our youth are brought back to life in social media posts that tag old friends in old-fashioned photographs that, like our memories, will never fade.

Eventually, MacMillans and Jody's closed, Planet X moved on again, and another raft of brave new world music and modes to live by started to kick the old New Romantics to the kerb. Dance floors once decorated with cobwebs and macabre hanging mannequins made way for hobos with skipping ropes; house music replaced house parties; water and E replaced poppers and Red Witch cocktails at raves, and superclubs, and spartan warehouse venues that fostered homogenous herds rather than gregarious wild animals who lived by the legend that we could be heroes just for one day...and my people and I did exactly that, every night.

Comments

Latest

The watcher of Hilbre Island

A blow for the Eldonians: ‘They rubber-stamped the very system they said was broken’

How Liverpool invented Christmas

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Heroes for one day, every weekend: memories of a Liverpool New Romantic

High-gloss, coiffed memories of an underground scene