Hanging 'The Little Caesar of Lime Street'

The Cameo murders, and Liverpool’s great miscarriage of justice

“Nobody has ever committed a crime after being executed,” so says Lee Anderson, deputy chair of the Conservative Party. Faultless logic: it is indeed difficult to achieve most things from beyond the grave. Anderson’s comments, made earlier this year, reminded me of a cautionary tale, three-quarters of a century ago, that amounts to one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in British legal history.

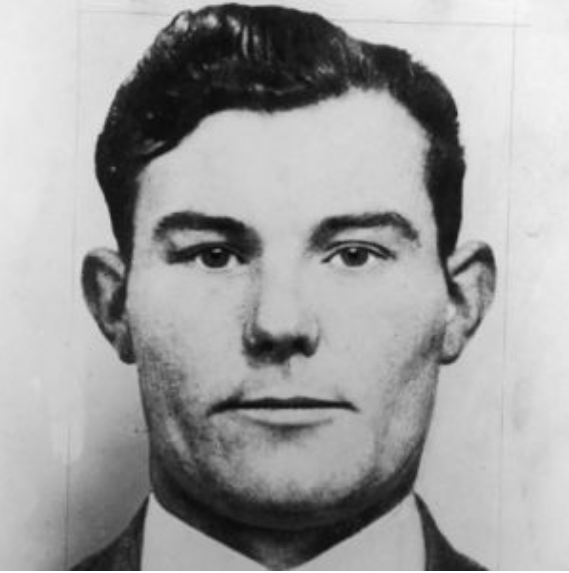

I’ve always been fascinated — and depressed — by the hanging of George Kelly and the imprisonment of Charles Connolly, so whenever a Tory politician moots the return of hanging, I’m reminded of their tragic story. The intricacies and difficulties of this police investigation — hampered by arrogance and corruption — should be required reading for all policymakers fond of capital punishment.

We begin in the quiet suburb of Wavertree.

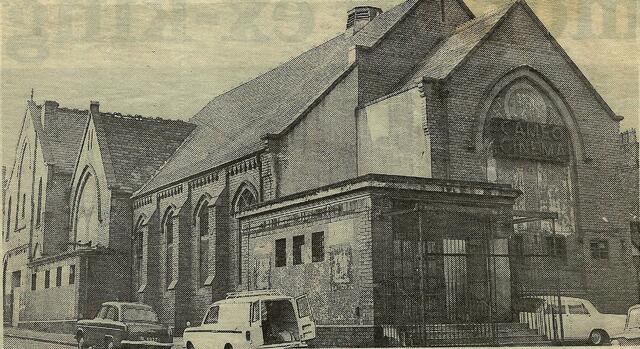

Let me take you back to the Cameo Cinema on Webster Road, on the evening of March 19th 1949. At around 9pm, the auditorium was packed for a film called Bond Street. In a case of life imitating art, this film involved a double murder and a manhunt.

These are the facts. At approximately 9.30pm, a cashier at the Cameo took the ticket takings for the night — £50.8s — in a blue cloth bag, to the back of the cinema, and up a spiral staircase. She entered the office of Leonard Thomas, the manager, and John Catterall, assistant manager, handed over the money and left.

Five or ten minutes later, an unknown man entered the office. After a brief scuffle, the intruder shot and killed both Thomas and Catterall. Both men had tried to resist the attempted robbery. In the mayhem, the cash would be left untouched.

Alerted by the loud bangs, the other staff of the cinema gathered outside the manager’s office. There was another volley of shots, as the gunman blew open the office door. He shouted at them to stand back, waving his gun about, before exiting onto the side street, disappearing in the night fog. He was said to have had dark features, a covering on his face, clad in a large overcoat and trilby.

Before rock’n’roll took over Liverpool, the most alluring American import was the Chicago gangster. It was as if a character from the film that was being shown that night had come directly from the screen and into boring, suburban Liverpool. Rationing was still in place, and the city was scarred with bomb sites. Liverpool was gripped by a post-war crime wave. Money was scarce, but guns, many of which had made their way to England from Germany as souvenirs from the war, were two a penny.

But this crime was particularly shocking. It gripped the city from the start, sparking one of the greatest manhunts in British history. Police officers knocked on 9,500 doors and took 75,000 statements. But there was no forensic evidence. All there was to go on were the witnesses who saw the gunman escape.

The pressure on the police was immense. It wasn’t until two months later in May that an arrest was made. A window cleaner, Donald Johnson — who was on remand with his brother on a charge of robbery — had been referred to the Cameo squad by Wallasey police. Johnson was one of many men who had been stopped on the evening of the murders, loitering by Smithdown Road. When questioned in May, he had known information that had not been made public — such as the murder weapon being an automatic. He claimed to have taken an oath on the Eucharist not to reveal the name of the perpetrator. A policeman, hilariously, dressed up as a priest to try and get the information out of him. The police coerced and pampered him, even paying for his bail on an unrelated charge, in the misguided belief Johnson would lead them to the murder weapon, or even the real gunman.

Johnson, who lived nowhere near the Cameo, had admitted to the police that he had walked up and down Smithdown Road on the night of March 19th, entering Toxteth cemetery many times. Some suggest the gun was hidden in the cemetery that night. Johnson made a telling statement to the police when he said “only the birds” would find the gun. Intrigued, I went looking for it myself, almost 75 years later, with a pair of binoculars, scanning the top branches of the trees. There are many unsavoury things to be found in Toxteth cemetery these days… But a gun is not one of them.

With no confession, the police charged Johnson as an accessory to the murder. However, because of the shoddiness of the police investigations, Johnson was acquitted on a technicality on the first day of his trial. His defence council successfully argued that his statements were inadmissible, after the police had promised to grant bail in another case. The police had a signed statement from an inmate of Walton prison claiming that Johnson boasted about being the lookout for his brother during the botched cinema robbery. That was now useless. Johnson could never be questioned, or tried again, for the Cameo murders.

Step forward the man who led Liverpool’s Murder Squad — Herbert Richard Balmer, known as Bert. A man whose philosophy was, when stuck in a hole you have dug, dig even deeper. A number of his investigations would later turn out to be reliant on shaky — perhaps concocted — evidence. He had been made Detective Chief Inspector the year of the Cameo murders and went on to be appointed Acting Chief Constable of Liverpool.

Three months after Johnson was released, Bert had taken a statement from a man named Robert Graham (remember that name), another inmate of Walton prison, who told him Johnson had confessed to the murders while awaiting trial. His statement was quickly buried. It was useless. Johnson would not do.

To leave the Cameo case unsolved would be the end of Bert’s career. He had to find someone else.

Let’s rewind to the day of the crime, and introduce another set of names. Earlier in the afternoon on March 19th, George Kelly, a 26-year-old jobbing crook, was on the lash with his friend Jimmy Skelly. And what a lash it was. It started in the morning with a few jars in the Midland Hotel, followed by the Empire on Hanover Street, the Royal William, the Liverpool Arms, the Coach and Horses (where Kelly ditched the catatonic Skelly), the Spofforth Arms, and finally, a nightcap with Kelly’s girlfriend, Doris O’Malley, in the Leigh Arms on Picton Road, not far from the Cameo. The evening finished at around 10:15pm, with Kelly more than a little marinated.

Kelly was a local celebrity in late ‘40s Liverpool. He was known for his fashion sense, modelling himself on the American film stars of the day. His criminal record was extensive. He regularly sold goods on the black market, and claimed to have connections with the city’s gangsters. The Daily Mail would later call him, with some exaggeration, ‘The Little Caesar of Lime Street’. Among the worst accusations he faced was beating a pregnant woman (which he denied). By all accounts, Bert despised Kelly, and maybe for good reason. Bert was also said to have had eyes for Kelly’s girlfriend, Doris. Kelly treated her terribly. According to Barry Shortall — in the excellent The Cameo Murders — Bert hated the way Kelly spoke to him — with a mixture of contempt and cheek. Kelly had been Bert’s first, and favourite, suspect in the Cameo job. On the Sunday morning after the murders, he had called on Kelly. He was to be disappointed. Kelly’s alibi, the lash, was cast iron.

There was one other lead. Just before the arrest of Johnson, Liverpool police received an anonymous letter from a person who claimed to have been involved in the planning of the robbery of the Cameo, but who had nothing to do with the murders. Here it gets even more complicated.

The letter claimed two men had been involved in the crime. The writer would come forward on the condition the police offered immunity. Examination of the letter revealed red lipstick on the envelope. Bert ordered his force to interview every single woman arrested in Liverpool over the past five years, a manifestly impossible task.

On May 13th, around the time Johnson was being questioned, Jacqueline Dickson — a petty thief and occasional sex worker — told the police she had sent the letter. It’s of note she came forward only following Johnson’s arrest. She refused to tell the police who the gunman was, but did say, after a great deal of thought, that a Charles Connolly, labourer and boxer, was involved. As quickly as Dickson appeared, she disappeared. She did not mention Kelly. Connolly was questioned on May 14th, denying any involvement in the case; claiming that he knew Dickson, but she was lying (as was her wont). Connolly claimed to have been at a dance with his wife and sisters the night of the murders — something that was corroborated.

It was only in September 1949 that Bert tracked down Jacqueline Dickson. This time, she claimed to have written the letter with a man called James “Stutty” Northam, her pimp. On the promise of immunity from prosecution they would give Bert what he so desperately desired — a statement implicating Kelly as the murderer.

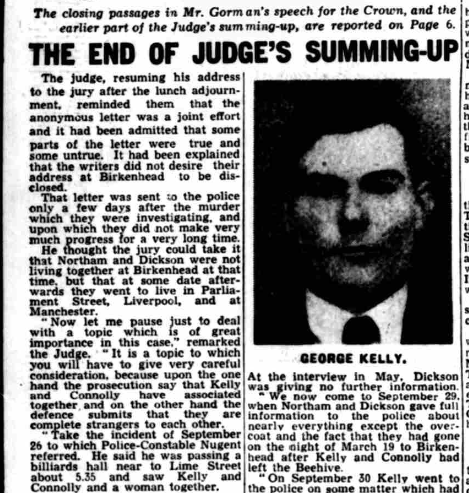

The three of them concocted a fiction worthy of Hollyoaks. Their statements revolved around the Beehive Pub, on Mount Pleasant. Dickson and Stutty Northam claimed that with Kelly and Connolly, they had planned the robbery in the afternoon of March 19th. Kelly, they said, produced a gun, telling Dickson, “I don’t care who sees me. I’m Kelly!” (You don’t need to be Martin Scorsese to see how weak that dialogue is.) With this, Dickson and Northam pulled out — being morally outstanding citizens, they didn’t want to have anything to do with an armed robbery. They claimed Kelly was the gunman, while Connolly acted as lookout.

It was all pure fiction. A far more likely scenario was that Stutty Northam and Dickson were both involved in the planning, and maybe even the execution, of the robbery, but the men they met in the pub were Johnson and his brother, not Kelly or Connolly.

George Skelly (whose elder brother was James Skelly, the drinking companion of Kelly on that fateful day), has written the definitive book on the case — The Cameo Conspiracy. Skelly claims the letter, which Northam and Dickson took credit for, was the work of someone known as ‘Norwegian Margie’ (Margaret Hanley), who had witnessed the actual planning for the robbery. She killed herself before the trial began — after intense pressure from Bert to make statements implicating Kelly and Connally, something she had refused to do.

Bert didn’t need her. At the end of September, he asked Kelly to drop-by at the police station (it is telling that Kelly did this of his own free will). In the words of the Great Defender, Horace Rumpole: “People who help the police with their enquiries often end up in serious trouble.” And indeed, Kelly did. On entering the police station, he was arrested for the Cameo murders. According to the police, when Kelly saw Connolly, he shouted to him: “You don’t know me, do you?” To which, with more than a little frustration, Connolly was obliged to answer in the negative.

Without any forensic evidence of any sort, and only the testimony of two convicted criminals, the case went to trial on the 12th of January 1950. Kelly and Connolly were to be tried together, under joint enterprise. It was to be the longest murder trial to date.

I would like to add, if I may, another character to this already packed production — Kelly’s remarkable barrister — Rose Heilbron, who has to be one of the most fascinating Liverpudlians you have never heard of.

Heilbron was born in 1914 in Liverpool’s once thriving Jewish community and attended Belvedere School — not so far from the Cameo Cinema. She was one of the first women barristers to be appointed King’s Counsel (and was the youngest KC since 1783). Heilbron, courtesy of the Cameo case, became the first female barrister to appear as leading counsel in a murder trial. She received only 15 guineas for the case.

Rose Heilbron’s daughter, Hilary, wrote in her biography of her mother, that George Kelly was, at first, furious with Rose’s appointment stating: “Whoever heard of a Judy defending anyone?” But, on seeing her spirited defence, he came to trust and appreciate her. For what happened next, he did not hold her accountable.

Stutty Northam was first to give evidence and went through the well-rehearsed series of events. He claimed he had lent Kelly his overcoat on the afternoon of the murders, for some inexplicable reason. He had then claimed to have met Kelly and Connolly in the following days, also inexplicably, where he had been given his coat back (like that would have been foremost in Kelly’s mind!).

The defence made short work of both Dickson and Northam. But there was a surprise witness for the prosecution: Bert’s secret ace. An inmate of Walton Prison (it seems more people worked for the police there than in HQ on Dale Street!): step forward again Robert Graham — The very same inmate who had provided Bert with the statement on Johnson. Graham claimed he had acted as go-between in Walton for Kelly and Connolly, the two not being able to communicate (this would later, too late, be shown to be false). Graham provided the crucial corroboration the police so desperately needed, regurgitating the story from the Beehive.

The jury failed to reach a unanimous verdict, which was needed in a murder case back in 1950. It was later shown that 11 of the 12 favoured an acquittal, which would result in a majority decision now. To much of the media, this came as a shock. It is worth remembering that this was a time when the population was, on the whole, more deferential to institutions. People tended to trust the police. The idea that the honest Bobby could concoct evidence would have been unimaginable to most.

The judge gave no more time to the jury, and immediately scheduled a retrial — this time, the defendants would be tried separately. There was no good reason for this unprecedented decision, as both had been jointly accused.

Kelly, still defended by Rose Heilbron, would be tried first. This was also strange, as alphabetically Connolly should have been first. This time the jury took only one hour to reach a verdict of guilty. Kelly was sentenced to hang. In a barrister’s report that was commissioned by the formidable Bessie Braddock MP in the 1970s, it was found that the “trial judge awarded the two principal witnesses for the prosecution [Dickson and Northam] twenty pounds each, not as expenses, but as a reward, which he was entitled to do under an Act passed one hundred and twenty-five years ago but which I have never known to be invoked.” Incredible.

One of the reasons why Kelly was sentenced to hang was because Graham had said in his statement that the assistant manager of the Cameo had been on his hands and knees when shot, information that had not been made public. The judge told the jury only the murderer could have known this fact. Indeed, he was right, but Graham had heard it from Johnson, not Kelly. If Graham’s first statement had been known to the defence, Rose Heilbron would have certainly got Kelly off. Graham was immediately released from prison after the trial.

All was not lost — there was a chance of an appeal, or failing that, a reprieve from the noose from the Home Secretary — James Chuter Ede. But Bert had played a rather clever game. The Liverpool historian, solicitor, and all-round eccentric Vincent Burke claimed that the reason why Connolly was brought into the conspiracy in the first place was because he was likely to plead guilty to a lesser charge, given the opportunity, thus saving his neck, and putting the final nail in the coffin of Kelly (if he hadn't done this, there was a good chance he would have dangled next to Kelly). He pleaded guilty and received a sentence of ten years. On his release, he tirelessly campaigned for a pardon for Kelly. A fighter to the last.

With Connolly’s admission of guilt, the prospect of an appeal, or a reprieve, vanished from view. Kelly went to the gallows shouting his innocence, hardly able to conceive his demise knowing in his heart of hearts he was not guilty of what he was accused. He was hanged by the strangest of middle-England heroes — Albert Pierrepoint. Kafka couldn’t have made it up.

Rose Heilbron had fought hard for Kelly. She did this because of her integrity and commitment to her profession. But, in the back of her mind, there may have been another reason too. Not only did she represent Kelly, but she had also represented none other than Donald Johnson, back in May 1949. If the police had not been shown to have failed that time, Kelly would not have dropped. It’s certainly not something that should be put on Heilbron, who was merely doing her job in defending Johnson, unlike the other characters of this sorry tale.

Once the police have been shown to lie, just once, it becomes impossible to distinguish fact from fiction. It is either a sound investigation, or it is not. There are either established facts, or only falsehoods. Meaning the ambiguities that are left in this case, such as the statements showing Kelly had indeed known Connolly before the murders, should be taken with a large pinch of salt. The police lied. Every shred of “evidence” against Kelly and Connolly is unsound.

The fight for justice went on until the end of the last century. A band of remarkable Scousers — including George Skelly, Luigi Santangeli (a local businessman), and the families of Connolly and Kelly — campaigned tirelessly for an appeal. In June 2003, both convictions were found unsafe and quashed. Connolly and Kelly were officially innocent. To every villain, a hero. Kelly’s remains were exhumed and a service was held, his daughter in attendance, at Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Connolly did not live to see this, dying in 1997. But make no mistake. This is not justice.

One cannot commit a crime after being executed. True. But one cannot be brought back to life after a posthumous pardon.

Comments

Latest

The watcher of Hilbre Island

A blow for the Eldonians: ‘They rubber-stamped the very system they said was broken’

How Liverpool invented Christmas

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Hanging 'The Little Caesar of Lime Street'

The Cameo murders, and Liverpool’s great miscarriage of justice