Did Florence Maybrick really kill her husband?

Arsenic and infidelity in the 1800s

There’s a drowsiness to Riversdale Road — maybe it has something to do with the mock gothic Aigburth cricket club on the corner of the road, the soundtrack of the gentle clapping of pensioners and cork hitting wood, as I make my way past.

I’m on a walk: not for pleasure, but for history. I’ve decided to re-trace the steps of one of the most tragic cases in Liverpool’s past — that of Florence Maybrick, sentenced to death in 1889 for having sex with a man who was not her husband. It’s a tale, but not an especially nice one, since it centres on one of life’s injustices: what men can get away with, and what women can’t.

I start at the Maybricks’ home. The house is an imposing, off-cream coloured Victorian villa; it has not changed much for over 100 years.

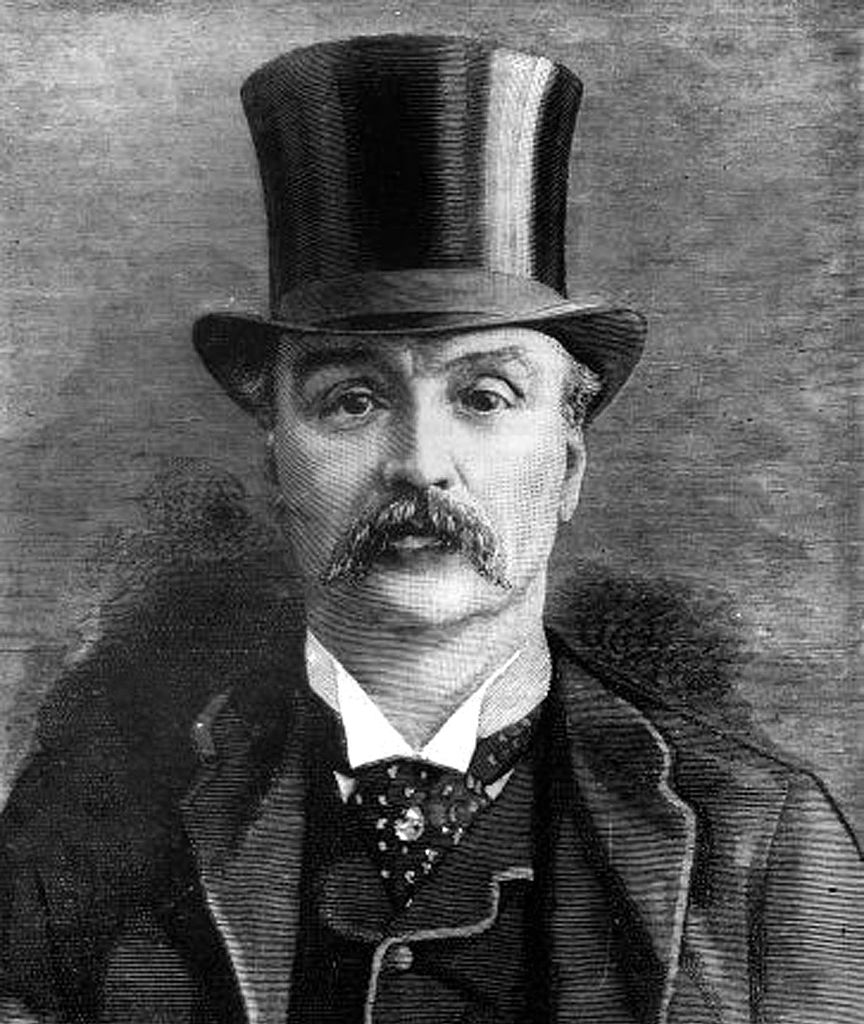

In the Spring of 1889, Liverpool cotton merchant James Maybrick died after an agonising three-week illness in this house. His wife, Florence Maybrick, was immediately accused of killing him with the arsenic from flypapers she had bought. I open my phone and search for images of Florence and James. She looks young and pretty, with full cheeks, and curled hair. She was described as the most beautiful woman in Liverpool. Florence was from the south of the United States and had an enchanting New World accent. James looks mysterious, with the wispy moustache of a Sherlock Holmes villain, wearing a black hat.

James and Florence met on a ship heading from America to England in 1880. He was 24 years her senior, with more illegitimate children than a recent prime minister, and a drug habit that would send Iggy Pop to bed early. He was hooked on some of the deadliest substances in existence, including arsenic and strychnine. A hypochondriac, in a paradoxical way he believed that these substances made him stronger and increased his virility (this deadly misconception was widespread in Victorian Britain, with many medicines containing arsenic). All the same, this libertine possessed all the prejudices of the English middle class. Freedom, he believed, was only a right for men like him. They got married just one year after the voyage, in Piccadilly, in 1881.

After two years living in America, the couple, now with a son and a daughter on the way, moved to Aigburth in Liverpool. Florence found the shift crippling. She thought the city was something of a cultural backwater; this being a time before the Lamb-bananas and Magical Mystery Tour bus. Not long after the move, in 1887, Florence found out about James’ second life: he kept mistresses, one of whom — living in Whitechapel, London — had borne him five children. Although James was in debt, the family upgraded houses and moved into the palatial Battlecrease in 1888.

Florence’s enthusiasm for her marriage began to wane. Much has been said about her subsequent infidelities, and it’s all too easy to get tangled up in the yarns spun by the press at that time. We can only be sure of one liaison, with a young Liverpool merchant, Alfred Briley. Florence said of this at her trial: “I was guilty of intimacy with Mr. Briley, but I am not guilty of this crime.” That would be her greatest mistake, as, unbeknownst to her, it was infidelity that she was on trial for.

In March 1889, Florence spent three days in a hotel on Henrietta Street, London, with Briley, presumably doing more than games of German whist, signing them both in as Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Maybrick. She was indiscreet to the point of recklessness. Maybe she had simply stopped caring. Around the same time, she started to enquire about procuring a divorce. James caught wind of the infatuation between Florence and Briley at the Grand National soon after. He smacked Florence across the face, hard enough for the doctor to have to examine her the following day. He didn’t reproach Briley at all.

As James lay dying in his bed in May 1889, sick with the illness that killed him, before suspicion was cast on Florence, she wrote Briley a letter. She handed it to the family’s governess, nurse Yapp, to post. Yapp by name, Yapp by nature: she was a nosey, busybody gossip, who despised Florence. She took Florence’s toddler daughter, Gladys, on a walk to the post office in Aigburth, and did the strangest thing…I can almost see it now: she handed the letter to the little girl, who, unsurprisingly, dropped it in a puddle. This was all the justification Yapp needed for opening the letter. The contents made clear Florence’s adultery and contained the infamous line: ‘He [James] is sick unto death.’ Yapp handed this letter, with great delight, to one of James’ brothers. Suspicion immediately fell on Florence.

(Everything about this case is not how it seems: some people, including Briley, thought the letter odd, and almost certainly tampered with.)

The fling with Briley sealed Florence’s reputation forever in the eyes of the law and press. When the judge sentenced her, he told the all-male jury that a woman who committed adultery was: “no better than a murderess anyway.” The evidence, or lack thereof, linking her to arsenic poisoning, didn’t matter much; her fall was damning enough.

James’ brothers, and the staff at Battlecrease, started to conspire against Florence. She had bought flypapers in April which contained arsenic, and had been seen soaking them in water in her bedroom by various members of the staff, including Yapp (this being a method of extraction for the poison). As the family cook testified during the inquest, there were no flies at that time in Battlecrease. The real reason for the purchase had been to use the arsenic from the papers for the treatment of acne, in a recipe Florence had learnt in Germany as a girl. This adds up, as Florence had attended a grand ball, the social event of the season, around this time. The purchasing of the papers had not been a secret, and Florence had made no attempt to hide the soaking. She assumed the purpose was obvious to all. During the countless medical examinations after James’ death, not a single fibre of paper was found in his medicine bottles, or in his body.

We do not know the reasons why the house united against her. Maybe they thought her adultery was evidence enough for something far more sinister, or maybe they just strenuously disliked her. But one thing’s for sure: something foul went on in Battlecrease House during May 1889. After James died, Florence was locked in her room for days, without any charge being brought against her.

I have a strange sense that she is still in one of those first-floor rooms. Three days after James’ death, Florence was taken away by the police in horse and carriage, down the drive of Battlecrease, a drive I am almost certainly trespassing on.

Although the day is warm, the garden of Battlecrease is cold. I leave this house, which carries so many ghosts. I look back for a final time, thinking I can hear something, but nobody is there. I walk down Riversdale Road. The large expanse of muddy water comes into view. I have hit the Mersey, just next to Garston Docks. The chemical plants of Ellesmere Port are to my left, across the water. The bleakness is a sight to behold. There is something beautiful about the view. It is my favourite place in Liverpool, if not the world.

It was to my left, in Garston, during the coroner’s inquest, that the case against Florence was first tested. There were three grounds for suspicion: first, the changing of the labels on James’s medicine bottles by Florence during his two-week sickness; second, she was accused of handing James medicine that supposedly contained arsenic; third, the letter to Briley showed a motive, of sorts — a crime of passion. But the inquest also unearthed just as many suggestions of Florence’s innocence: James’s doctor testified that he was a habitual drug taker, swallowing large doses of arsenic on a regular basis; the family’s cook described Florence’s ceaseless work nursing James during his final days; the toxicology report exonerated Florence still further: the amount of arsenic in James’s body was insignificant, far less than the smallest recorded fatal dose (this small amount was easily explained by James’s well-known addiction to the poison, and likely entered his body a long time before his sickness).

Yet the press refused to let the facts get in the way of a juicy story. Much was made of Florence’s beauty, and even more of her infidelity. Fears were stoked of the domestic “silent assassin,” the disloyal wife who could easily do away with her bothersome husband with a drop of tasteless arsenic.

This was the age of the suffragettes, the great awakening. A patriarchy that had been in place from time immemorial was slowly beginning to crack. The elite acted swiftly. The inquest jury found that James died as the result of poisoning and named Florence as the person who had administered arsenic. She was committed to the next Assizes court in Liverpool.

I move away from Garston, and walk along Otterspool Promenade, towards the city centre, heading to St Michael’s train station. Before boarding a train for Liverpool Central, I make a detour via Lark Lane Community Centre, which used to be the local police station. It is a large red brick building, and better suited to a rural village. It was here that Florence was taken after the inquest. Lark Lane has changed so much over the years, it is hard to imagine Florence ever having been here. When I do picture the scene, it is with an almond macchiato, unashamedly, in Milo Lounge. I board the train at St Michael’s, and head to St George’s Hall, the location of the trial.

Underneath the gold-leafed grandeur of its rooms and halls, deep within the labyrinth of St George’s, exists a holding cell. It was here that Florence sat before and after the verdict was passed. Not many visitors seek it out. There is no natural light; there is a slight odour. I close the gate behind me, sit on the cold bench, and gaze at the names and dates etched into the wall. You can almost touch the history. So many lives came to an abrupt end in this room. I leave, ascending a spiral staircase to my right, which leads straight into the dock of the courtroom.

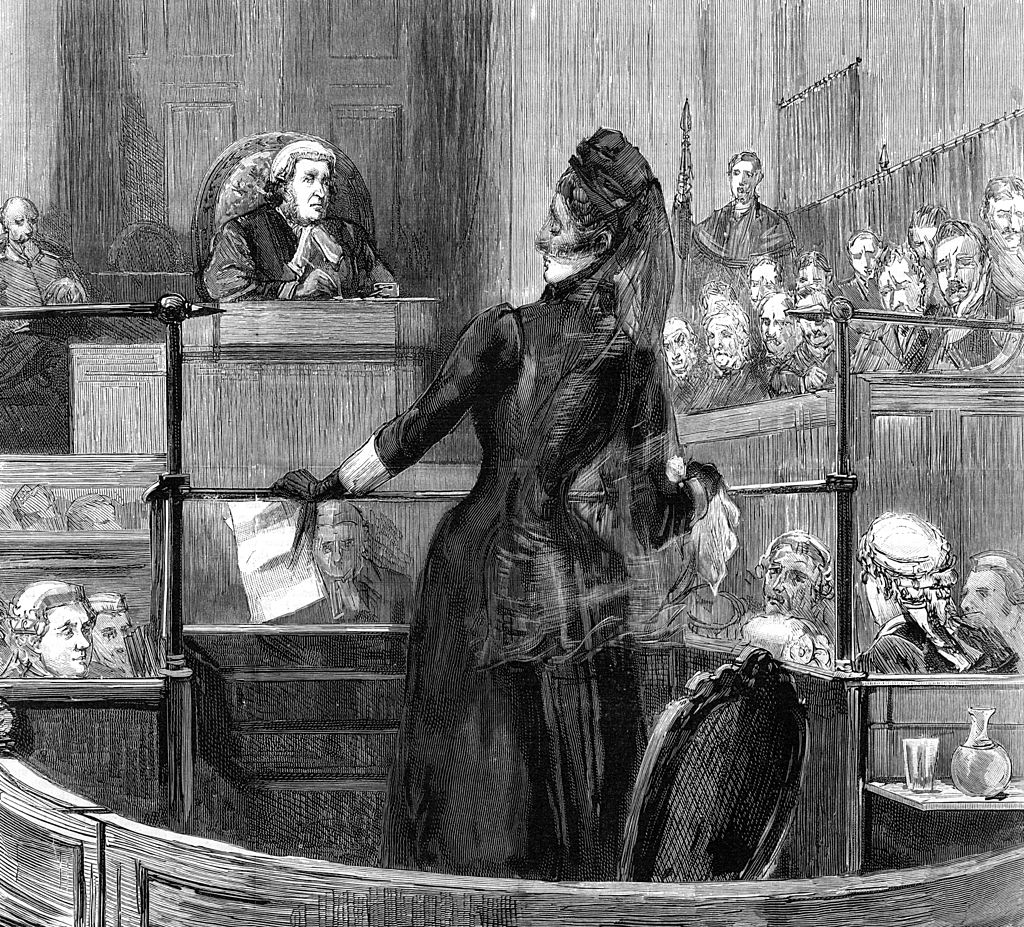

The judge, James Fitzjames Stephen, sat in a green seat. A horrible red beard covered his jowly face like moss. He dressed in all the absurd pomp and regalia of the Victorian judge. Florence emerged from the staircase. She stood, where I am standing, ready for sentencing. She was spat upon by members of the public. Someone shouted “whore” from the gallery. It was the expression of what Margaret Thatcher called, with great nostalgia, “Victorian values.”

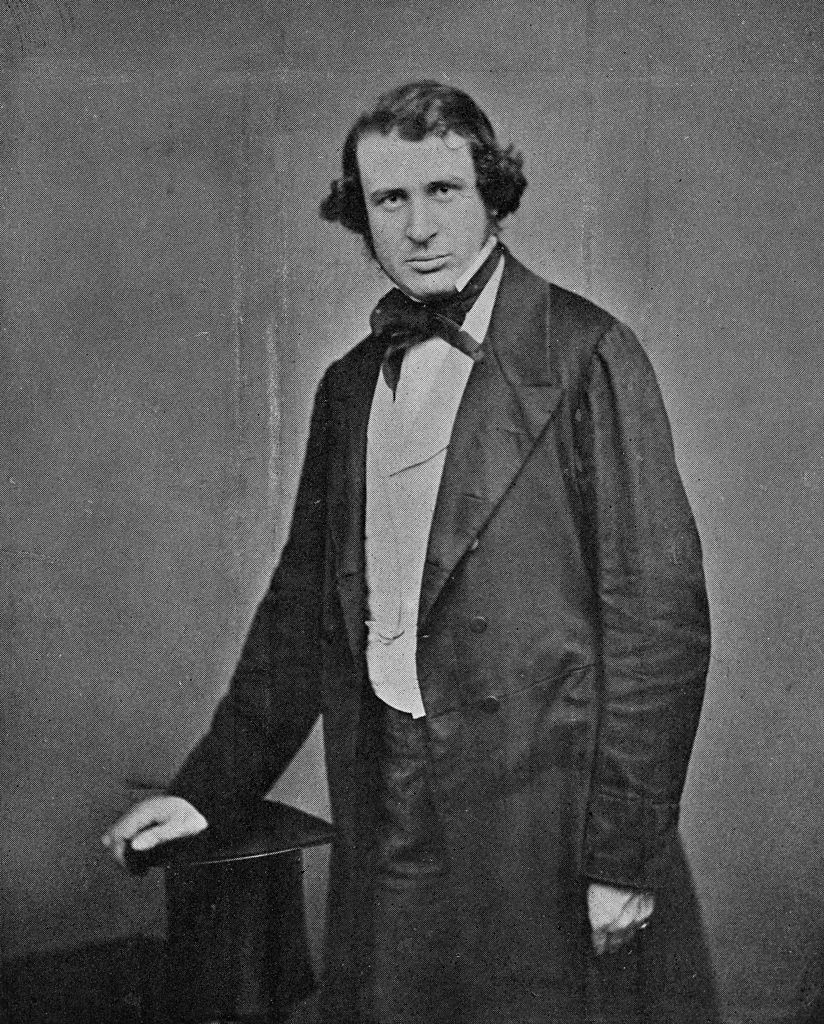

The room was silent during the judge’s summing up. The trial had been a farce; it seemed impossible to Florence’s barrister, Charles Russell, future Lord Chief Justice, that any jury could convict someone with such little evidence. But then the judge spoke: “Members of the jury,” he said, “Your own hearts must tell you what it is for a person to go on administering poison to a helpless, sick man, upon whom she has already inflicted a dreadful injury — an injury fatal to married life; the person who could do such a thing as that must be destitute of the least trace of human feeling.” The jury deliberated for less than 40 minutes. “Morality” triumphed over evidence. Their verdict was Guilty.

The judge donned his small black rag, on top of his judicial wig, and the reality of things suddenly dawned on the baying mob outside St George’s Hall. The weather turned, and rather than wanting her to hang, the Liverpool crowd began to scream for a reprieve. The jury, uneducated, and I repeat, all-male, with not the slightest knowledge of medicine, had been totally swayed by the judge’s summing up. Florence Maybrick was sentenced to death. A woman who committed adultery, was deemed a woman who could kill. Forget the many mistresses of James; forget the long nights he spent in brothels; forget his army of illegitimate children. Florence had dared to have sex for pleasure, with a man who was not her husband and, according to the judge, and Queen Victoria, that meant she had to drop.

Leaving St George’s Hall, I sit on its steps overlooking Lime Street. Florence was, at the final minute, saved from the gallows by the Home Secretary, who stated there was ground for reasonable doubt as to whether the arsenic administered was the cause of death. The Queen was furious that “so wicked a woman should escape by a mere legal quibble.” For as long as she reigned, Florence would not taste freedom.

Who, or what, killed James? Perhaps this doesn’t matter so much, compared to what happened to Florence. It is perfectly possible his death was caused by the medicine sent to him by his brother, Michael, from London, in April 1889, which contained strychnine. James knew he had taken an overdose of strychnine and told friends as much at the time. More likely still was gastro-enteritis, exacerbated by the withdrawal, not the consumption of arsenic. Although some, including detective fiction writer Raymond Chandler, continued to think Florence guilty, it was without any evidence, of any kind.

There is a curious epilogue to this story. Just over 100 years after the trial, a diary, written, or made to look like it was written, by James Maybrick, was found, possibly in Battlecrease House. The person who wrote it was, or was pretending to be, Jack the Ripper. Nobody knows for sure if the diary is genuine; however, it is one of the most analysed documents in the world, and the fact it has not been declared a forgery gives it some credence. But that’s a story for another day.

I head home. I feel overwhelmed. Florence never saw her two young children again, dying a recluse in the United States, alone, at the age of 79. She served 15 years in prison, some of which were spent in solitary confinement. It is the end of my tour. It seems to me the past is not so very far from our grasp — scratch that veneer ever so slightly, walk in the shadows of those who came before us, and it all comes shining through.

Comments

Latest

Cheers to 2025

Searching for enlightenment in Skelmersdale

I’m calling a truce. It’s time to stop the flouncing

The carnival queens of Toxteth

Did Florence Maybrick really kill her husband?

Arsenic and infidelity in the 1800s