Born into a bed pan, lived a life of shit

Lesbian mothers in the 1970’s lost their children. One Liverpool nan wants an apology

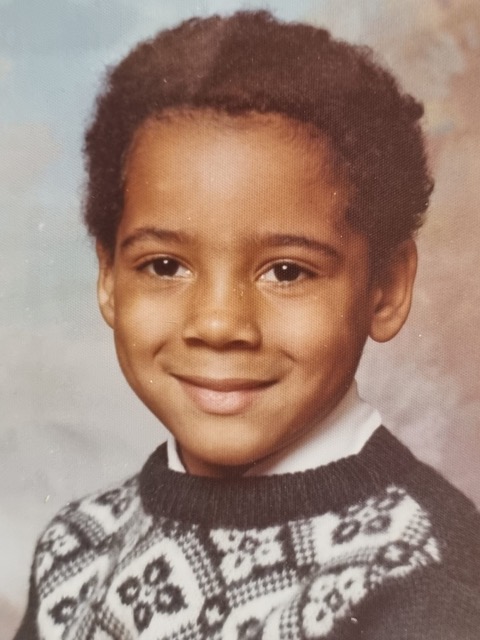

Judi Morris has a go-to phrase to describe her son’s life: “He was born into a bed pan and lived a life of shit.” That birth, and that bed pan, came in 1972 at a hospital in Sutton Coldfield. The midwife was clueless — she handed Judi the bed pan “in case [she] needed to go to the toilet”. Then George Morris landed in it.

Sadly, much of the subsequent 51 years was the “shit”. Two years ago, George died from major organ failure at the Royal Liverpool Hospital. Judi was at his bedside, holding his hand as he closed his eyes for the last time. And wondering: how different might things have been if George wasn’t taken from her when he was 18 months old.

Judi is now in her mid-seventies. She’s a great-grandmother. She’s also my mother’s former partner and a presence in my life for the past 35 years. She’s also one of many, many openly gay women who had their children taken from them in the 1970s and 80s. Living openly as a lesbian of South Asian origin in a homophobic and racist country was no easy task. In her own words, she was “off and on” back then. She’d date men and women. It was just easier that way.

Settling down with a coffee (and a cigarette or two for Judi) at her kitchen table in her Liverpool home is an event. Expect to be there a good few hours with no topic of conversation off limits. From last night’s episode of Corrie, to the plight of refugees to the latest lurid antics of the Tories. It’s all fair game. But today I’m here to talk about George. Her second eldest son — and the son she wishes had such a different start in life.

George was a healthy baby with mixed heritage. Judi’s parents were from India and came over before Partition. Judi herself was born and raised in Sutton Coldfield and George’s father, whom she met whilst working at the local hospital, hailed from Nigeria. But 18 months into George’s life, his father decided he wanted full custody of the child. The way Judi sees it, he didn’t really want George at all. He knew Judi was openly gay, and “out of spite” he wanted to take her son from her. That’s the only explanation she can think of.

Whatever the explanation, she faced an uphill battle. Rights of Women formed a Lesbian Custody Group in 1982 to back lesbians being discriminated against in the courts. In 1986 they published a report showing that at its worst, 90% of lesbians were losing contested cases.

Judi did what any other parent would do in the same situation and tried to get legal help — without success. One solicitor refused to help, simply saying “lesbians won’t win”. It was blunt and harsh. It was also, sadly, pretty accurate. Eventually George’s father was awarded full custody. “That’s the way it was in those days”, Judi says. “He applied to the court and got it.” Social services weren’t involved. There were no papers served. Judi was ordered to simply hand her baby over. And so she did.

That’s when something happened that would change the course of George’s life. George’s father gave him to private foster parents. White foster parents. Judi had no knowledge of it. This was a perfectly legal practice back in the early 1970s. Private foster parents were not vetted: “There was no regulation or control over it,” Judi recalls. “He left George with a couple you wouldn’t leave a dog with in a shitty, smelly little flat.” The foster parents weren’t fit to have children. They were abusive. George’s father would take George back for a few months when he was back in England, then put him back with the foster parents. Judi had no contact with him.

It was only after Judi moved to Liverpool in 1974 that she got a message from Sutton Coldfield social services, telling her to come and collect George from the neglectful foster parents. If she didn’t, he’d end up in the care system. The father was nowhere to be seen.

Opening the window to let the cigarette smoke out of the kitchen, Judi takes a moment to gather herself. She’s clearly haunted by the memory of seeing George for the first time in nearly three years. When she travelled down from Liverpool to Sutton Coldfield to collect him, she took her eldest son, who was a few years older than George, with her. As soon as George saw him, he exclaimed “My brother!”, throwing his arms around him. He’d remembered him. But as for Judi, he didn’t recognise her. When social services told George this was his mother, he laughed and said, “No, my mum’s dead.” That’s the story he’d been given.

For Judi, the real battle was about to start. She was told she could only keep George for the weekend. After that, she must give him back or she’d be issued with a Magistrate’s Bench Order to have her arrested. She didn’t. “I had a lot of people (in Liverpool) who would have hidden him. And I didn’t care going to prison,” she says. For whatever reason, they didn’t issue the Bench Order, but the fight wasn’t over. Judi had to represent herself in court to regain custody of George. She remembers that the legal profession was still refusing to help unless she denied her sexuality — one solicitor said she would only act for Judi if she pretended not to be a lesbian. “I said no,” recalls Judi, “I’ve done enough pretending, and I’m not pretending anymore.” Despite spurious claims by the returning father that Judi was bipolar and couldn’t care for her son, the judge ruled in her favour, and she won. With that, George was home.

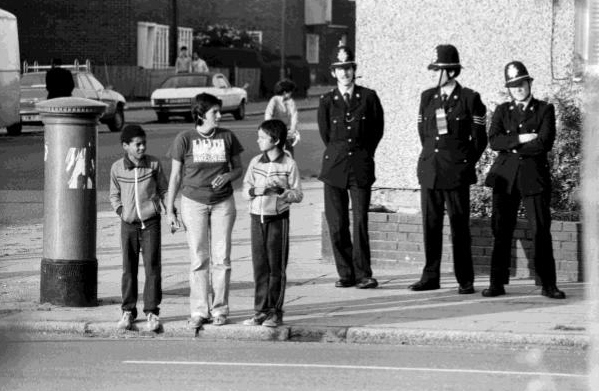

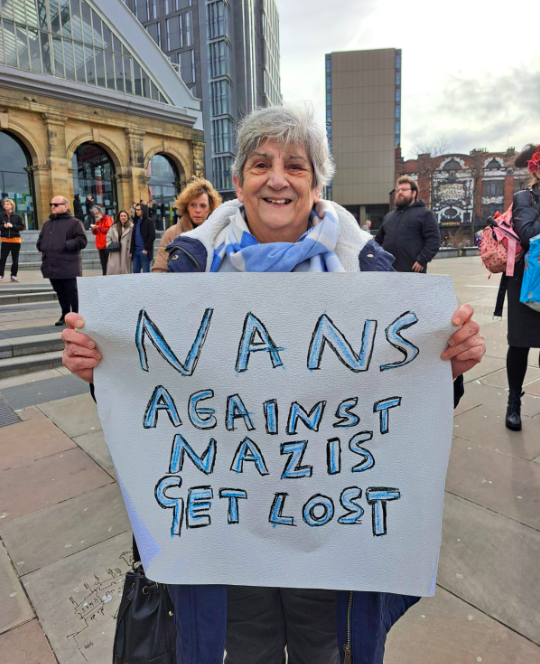

Activism has always been in Judi’s blood. Last year she proudly stood outside Liverpool Lime Street Station waving her Nans against Nazis placard, protesting against fascists who rioted outside the Suites hotel in Knowsley. “If they want the nonces out, why don’t they start with Prince Andrew?” she fumed. She’s been on numerous Pride marches and helped to set up the Parents of Black Children group in Liverpool while her boys were at school. When the Toxteth riots of 1981 took place just outside her front door, Judi’s flat was used as a makeshift medical centre for victims of the police who were “hitting anyone who was black or just there”. As a working-class lesbian single mum with black children, there was a lot to fight for and against.

But for George, the abuse and neglect he suffered in his early years meant the damage had already been done. When he came back to live with her, “he’d stand in the kitchen corner and cry. I’d ask him if he was hungry. He’d say yes. So clearly he’d been stopped from having food.” Was there physical abuse? Probably. Judi tells a story of George being forced to stand on rice, or on one leg, and if his feet touched the floor he’d get a belt from his dad. This went on for a while before he’d be put back with the foster parents where George would go on to witness domestic violence. Months into George’s arrival in Liverpool, he was showing signs of this trauma. A headteacher in the primary school he was enrolled at was concerned. She told Judi that George was claiming to have double vision. He was only five years old. He’d also defecate up the walls. He had been — in her words — “brutalised”. Brutalised by his dad, by the foster parents; brutalised by the whole system.

There were lighter moments. Judi remembers one day when she took him to the psychiatrist’s office for a diagnosis, she went to sit down on the chair, but George whipped it out from under her and she ended up on the floor. George sat on the chair, looked at his mum and said “what are you doing down there, you daft bugger”. He was only seven. “He was a swine,” Judi laughs.

But George stayed troubled. At the age of 12 he was sent to the notorious Dyson Hall, a youth detention centre in Liverpool that closed in 2008 and has since been the subject of sexual abuse investigations. George had snapped and beaten up a fellow pupil, who had been racist to George every single day for months. He was locked up for a year; the other kid went unpunished. George came out hardened. At the age of 16 he was sent to adult prison for another violent offence. “After that, he just deteriorated,” Judi says.

Judi’s eldest son, the one who lived with her since the time he was born, grew up balanced and happy. Now a medical professional, working in Liverpool, he too, like many kids, suffered racist abuse in school and on the streets. But with George, Judi insists irreparable damage had been done to him at an early age. He was too far gone.

As an adult, George flowed in and out of Judi’s life. In and out of prison too. She knew he was still living in Liverpool, he knew where she lived. He’d sometimes pop round out of the blue and steal from her. “He’d rob your eyeballs and come back for the sockets,” she regales. Judi remembers one incident with a wry smile on her face. “There was a knock on the door. George bundles this baby into my arms and asked me to look after him for a bit. Then he got off,” Judi didn’t know who the baby was or who it belonged to. But the next morning sheepish George returned for him. It seemed he’d been arrested with his girlfriend for robbing curb crawlers. “That’s why he wanted me to mind her baby — so he could go out robbing!” She laughs at this. In some ways, it is funny — in all the stories she tells, we keep coming back to how his character was endearing. But he also had a darker side. He was abusive to his girlfriends, he ran around with the gangs of Liverpool 8, and he started taking heroin.

Judi last saw George a couple of months before he died. He looked different. He was suffering with alopecia; his hair and eyebrows had fallen out. “He said he was off the drugs and he was going to rehab. He said, “I’m getting too old for this.” Judi believed him. Their relationship had been fractured for so long, but she saw an opportunity for reconciliation. “I said to him, ‘When you come out of rehab, let’s go out for our tea… let’s see if we can mend something between us.’” He seemed to like the idea. But they never did. A couple of months later, George’s then-girlfriend pushed a note through Judi’s letterbox stating that he was in the hospital, dying.

It was too late for George. He wasn’t in rehab, and he’d been injecting heroin into his body for such a long time that all his major organs were failing. When Judi arrived at the Royal, he called out for her. She held his hand and wanted him to be free from pain. “I told him it was okay to let go,” she remembers. He drifted off peacefully.

Nearly two years on from George’s death, Judi says she thinks about him every day. She knows George hurt people, but he was still her son. There were things about him that were loveable. And she also wonders what could have been if the authorities hadn’t sided with his father all those years ago. “He never really recovered from it… if he’d have been left with me, would he have had a better chance in life?” she ponders. She probably knows the answer.

I ask Judi if she wants an apology. She says she does. She thinks the hurt that they — the courts, society, social services — caused her needs to be acknowledged. “He (George) was displaced and dumped,” she says. Taken from his mother, split up from his brother, he never got to see his grandmother until he was back with Judi, he lacked a family. He lacked love.

Still at Judi’s kitchen table, we make another coffee (granules – the “hard stuff”, she likes to call it) and let the dogs out in the yard. She slips in the chance for a quick fag, then tells me I met George a few times when Judi was with my mother, and he was funny and kind to me. I confess that I don’t remember, which is a shame. For the last 35 years that I’ve known Judi, I now regret not getting to know him too, or even asking about him. Perhaps I thought it would be too painful for her.

It is painful — that’s why Judi’s story needs to be told. She thinks the gay community needs to be more aware of “what’s gone on”. It’s just over 20 years since Section 28 was repealed. Homosexual acts in the UK were only decriminalised in 1967 (1982 for Northern Ireland). This is recent history. “A social context is important to understand how backward this country was,” she insists. “It’s like everything has been forgotten about. Like it didn’t happen. That’s the value of this. Let’s be honest about what happened.”

Let’s be honest about something else too. When a black, middle-aged man with a long string of criminal convictions dies in a Liverpool hospital due to complications from heroin abuse, it’s a story that perhaps won’t elicit huge sympathy automatically. But it’s a story that should at least be understood. Britain has changed for the better since George was robbed from Judi just 18 months into his life. But people like Judi, who fought for that change, suffered incredibly. They still do. That surely deserves recognition — and yes, maybe even an apology.

Comments

Latest

This email contains the perfect Christmas gift

Merseyside Police descend on Knowsley

Losing local radio — and my mum

And the winner is...

Born into a bed pan, lived a life of shit

Lesbian mothers in the 1970’s lost their children. One Liverpool nan wants an apology