At the University of Liverpool, pressure builds over Gaza

‘You can't uphold the integrity of academic work when your university has been bombed to the ground’

Dear readers — “If our institution can't speak up, then who the hell can?” were the words of one protestor at the University of Liverpool regarding the institution’s stance on the war in Gaza. As they have on dozens of other campuses across the world, students have set up an encampment in support of Palestine, demanding the university publicly calls for a ceasefire and separates itself from businesses associated with the Israeli military. But what is the University of Liverpool’s role in global politics — if it plays one at all? That’s today’s story by Abi.

Editor’s note: As always on a Friday, this piece is paywalled halfway down. To read the full story, you’ll need to be a paying member of The Post, which costs just £7 a month and gives you access to our entire back catalogue of features and investigations, as well as invites to our future events. We’ve had a fantastic month of growth so far, but we’d love for you to help push us over the line to meet our target of 75 new members by June. Click that button below to support us, and to help us fund reporting on more stories like this one.

Your Post briefing

A 74-year-old retiree has been told he’s not British after nearly 50 years of living in the UK. Nelson Shardey is now facing costs of up to £7,000 to retain his residency over the next decade, with a further £10,500 to access the NHS, as part of a 10-year route to settlement. Shardey moved to England from his birthplace of Ghana in 1977, and currently resides in Wallasey, in the Wirral, where he previously ran a newsagents called Nelson’s News. He has studied and worked in England for 42 years, has performed jury service, and in 2007 received a police award for bravery. Mr. Shardey is now taking the Home Office to court, claiming he should be treated as an exception due to his services to the community.

Liverpool City Council are launching a public consultation for a £4 million scheme to upgrade Anfield’s high street. The consultation on Wednesday 22nd consists of three public events showcasing how the high street and connecting side roads would be revamped. The proposal improves walking routes, widens footpaths, plants more trees, and installs underground bins. Councillor Dan Barrington claims the project “will have a major impact on the day-to-day quality of life” for residents.

And yesterday Councillor Richard Kemp was sworn in as the new Lord Mayor of Liverpool in a Town Hall ceremony. Kemp moved to Liverpool in 1974, and has filled a number of roles here, including cabinet member and leader of the Liberal Democrats Group. He is currently the councillor for Penny Lane Ward, and says he intends to dedicate his year in office to support care leavers throughout the city.

At the University of Liverpool, pressure builds over Gaza

“This is decolonisation, this is real democracy, this is the real university.” I’m sprawled on the grass of Abercromby Square at the University of Liverpool, watching a man in his mid-40s speak to a group of students who’ve gathered around him. He’s holding a microphone wired to some sort of mobile speaker, but it appears to be off, or broken. In a muffled voice he praises the encampment at the university — a protest by students in support of Gaza following the war that broke out in October — which now has over 50 people camping in tents and sleeping bags around the square.

When it was formed last Monday, the Abercromby Square encampment was one of five similar installations at UK universities. Today, it’s one of 25. Inspired by the actions of other students in America, Spain and around the world, these camps seek to put pressure on universities to condemn Israel’s actions, divest from companies linked to the Israeli military and show solidarity with the Palestinian people.

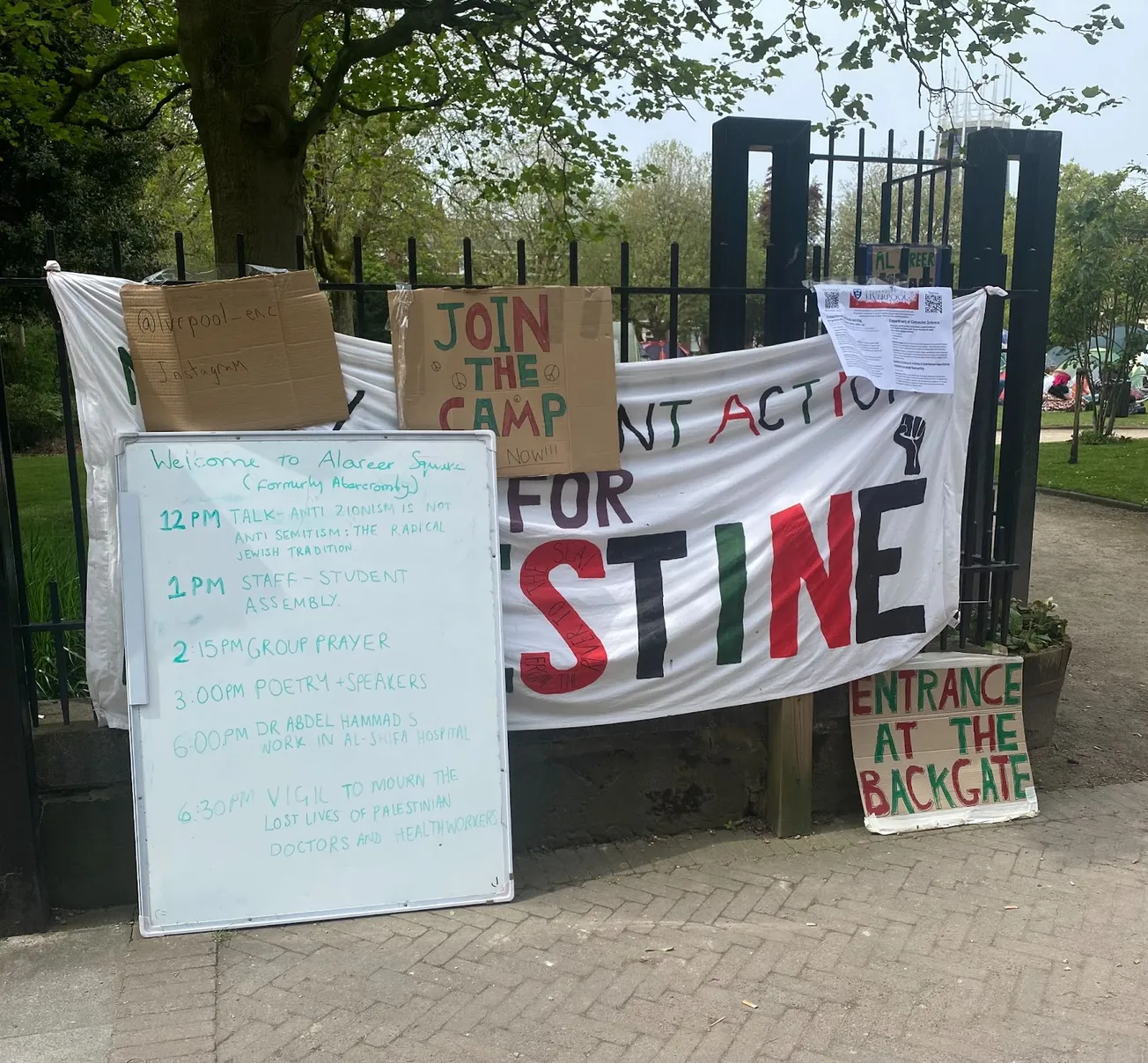

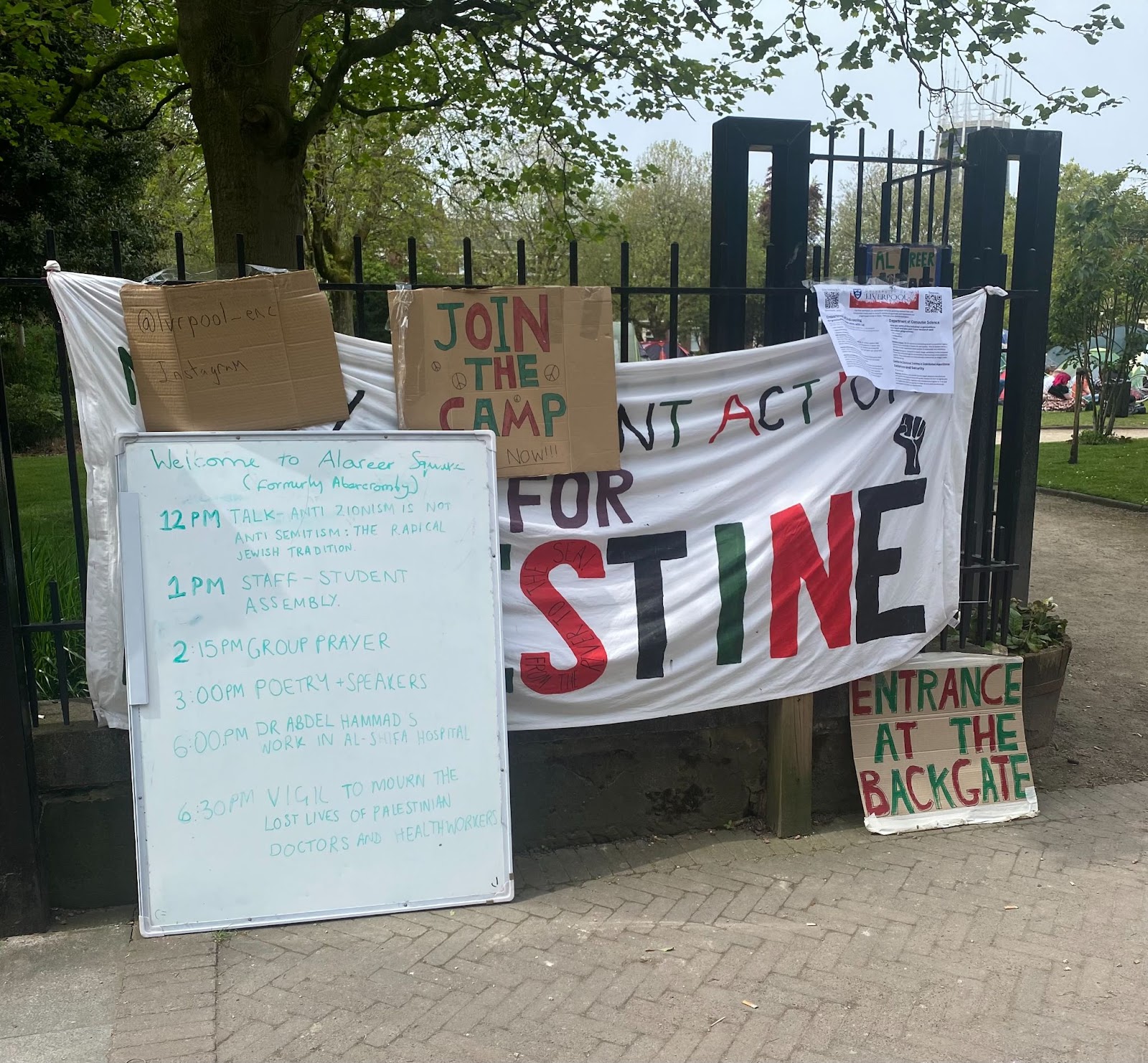

“It feels like the student protests have cut through a lot of the noise and broken out into the whole world,” says one student, who asks to remain anonymous. She’s around 20 years old, but I’ve been told she’s the “head of PR” for the encampment group, who are now calling themselves the Students of Alareer Square. This unofficial name change is in memory of the 44-year-old Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer, who was killed in an Israeli military airstrike in December. It replaces the square’s original title of Abercromby, the name of a 19th century commander of the British Army in Egypt.

The Liverpool encampment began last week, after the annual Merseyside Mayday March. That rally usually centres around trade unions, but this year it had a particular focus on the conflict in Gaza, with hundreds of workers across the region marching in solidarity with the Palestinian people. “After the rally, one girl just grabbed a megaphone and announced we were starting an encampment,” the student PR explains. “Obviously there was quite a small group of us at the beginning, but since then it’s just snowballed.”

A vast sea of tents are pitched around me; strips of cardboard and fabric are laid out on the grass with ‘Free Palestine’ and ‘Join the camp’ painted on them. At the front of the square, a large circle of people gather for today’s activities and debates, with dozens of students trickling in on their lunch breaks to hear specialist talks from lecturers, academics and students about Israel and Palestine.

The aims of the Liverpool encampment are simple, the student tells me. They hope to push the university to financially boycott companies implicated in the war (such as Jaguar Land Rover and BAE Systems, research partners at the university’s School of Engineering who have also supplied Israel with military technology); publicly call for a ceasefire; launch an investigation into how research projects may have contributed towards the war; and disclose how it spends investments and student loans on a quarterly basis.

Simple? Maybe not. Divestment is by no means an easy feat, and thorough investigations into how research projects may have contributed towards the war are likely to take years to complete. Since the camp-out began, the students have been in touch with the university to discuss these demands, and have had little communication back. So far, the university has issued a statement publicly recognising the encampment’s existence; they told The Post that the “Campus Support Team have been in regular dialogue with the protestors and have been working to ensure a safe environment around the protest, for all concerned.”

“The fact that our [student loans] have been taken out of our hands and spent on things that we haven't consented to and a lot of students don't agree with, it’s undemocratic,” the student head of PR says, noting that a lot of people who pass through Alareer Square have been horrified to learn about some of the companies linked to the university. She adds that in recent years, the university has made an attempt to extradite itself from its historic links to slavery, renaming buildings and acknowledging profits made via the transatlantic slave trade. “I think it's ironic because moving forward from that, they should have been doing everything they could to be as ethical as possible,” she says, explaining that the university needs to come down from a “moral stance of being an anti-colonial campus” when it’s continuing to fund a “colonial project like Israel”.

Whether the university has a moral and political responsibility to take a stance on Gaza is a question I hear throughout my time at the encampment. There are wider implications here: what is the University of Liverpool’s role in the world? Should they be speaking out on the destruction of educational institutions in Gaza? And in light of the numerous statements, helplines and websites the university created in support of Ukraine following Russia’s invasion in 2022, why has Palestine not received that same treatment?

We spoke to numerous lecturers and staff, many of whom hold vastly different views on the topic. While some felt the suggestion the university should be weighing in on Gaza was ridiculous (and one told us the encampment does not seem like a “safe space” for Jewish students) others said they was internal pressure being place on the university to break their silence. “The very nature of remaining silent is just as political of a decision as offering a statement,” one told us. Clearly, tension exists within the university on this point. It’s a tension that will only build.

Latest

Locals think big events are ruining Sefton Park. Are they right?

The Northern Arc: A Liverpool/Manchester vanity project or genuine driver of growth?

Never mind Shanghai. Germany's energy capital could jumpstart Liverpool

Why is Birkenhead out of work?

At the University of Liverpool, pressure builds over Gaza

‘You can't uphold the integrity of academic work when your university has been bombed to the ground’