A legacy of lies: The downfall of a Liverpool conman

'I hate Rob Ware and wish I’d never met him'

By Matt O’Donoghue

“He’s taken everything from me; my health, my dignity and self-respect, the family legacy… Five generations it took to build that business up. All of it is gone because of him.”

Chris Snow is peering over the top of his rimless glasses as we chat outside Court 5 on the fourth floor of Liverpool Crown Court. It’s October 2023 and rain hammers down from a slate grey sky onto Derby Square below. A complex fraud trial that’s lasted three months has just ended, and I ask Snow — a victim in the case — what he thinks of the conman who’s been sentenced to eight years. He pauses to measure his words.

“He was my friend. We played badminton together every week. He even came on holiday with us. I trusted him like he was family. Honestly, I hate Rob Ware and wish I’d never met him.”

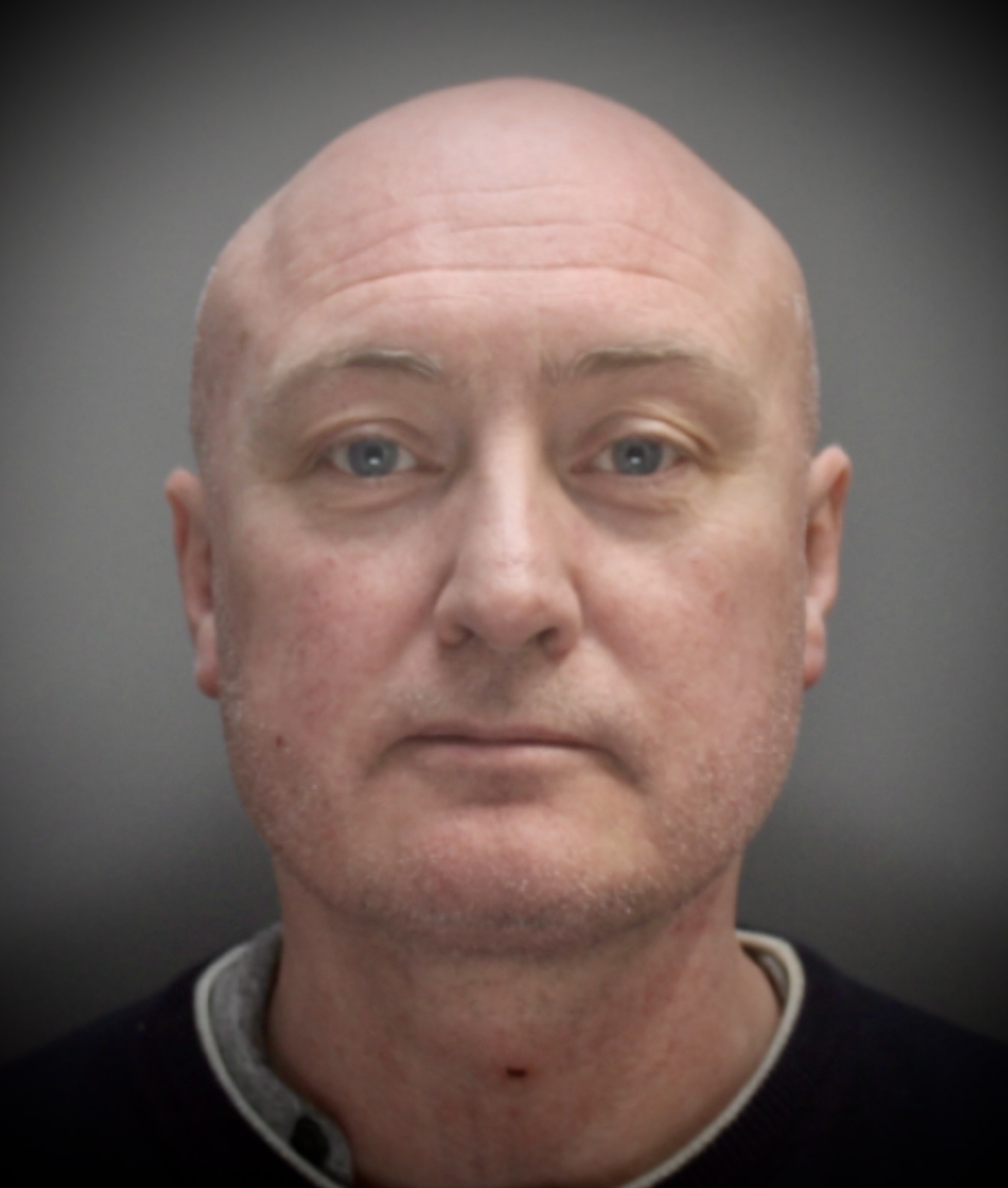

Chris Snow is far from alone. Robert Richard Herbert Ware has sailed through his 43 years leaving a trail of destruction in his wake. The actions of this one-time solicitor-turned-property developer — and now prisoner — have ended careers, sucked savings accounts dry and closed companies. Ware’s actions even took down Liverpool’s oldest family-run building business: WH Snow was founded in 1896, and by 2019 they employed 17 full-time staff, but the business is currently in the process of being wound up.

“It took 123 years — five generations — to build up that company, and a four-year friendship with Ware to knock it down,” says Snow. “As it was with my father, and their father’s fathers before them, it was supposed to be my son’s inheritance.”

Aged 70, Snow says it’s too late for him to start again. There’s sadness and regret in his eyes as he speaks with a soft Liverpool lilt.

The Post has closely followed the slow motion downfall of Robert Ware. He was arrested six years ago, tried over 12 weeks for fraud this summer, and finally sentenced last month. But our investigation into the collapse of this particular house of cards is more than a morality tale. It takes us deep into the failing heart of the institutions designed to protect us, as we celebrate this rare success in Merseyside’s fight against fraud.

“Rob Ware wasn’t robbing Peter to pay Paul,” Snow says outside the courtroom. “He was robbing Peter and Paul to pay himself. WH Snow is finished, and that happened on my watch. I’m ashamed of myself.”

The shame that Snow feels is not unusual among victims of fraud. This may be why the National Crime Agency estimates almost nine out of every 10 instances of fraud go unreported. An investigation by the consumer group Which? found that fewer than one in 20 cases are solved. A world-weary detective once told me: “The Police don’t like fraud because it takes forever to investigate. The Crown Prosecution Service doesn't like it because trials last months and cost a fortune. And juries don’t like it because it’s so complicated.”

The total value of alleged crimes committed by conmen like Robert Ware last year — those that actually reached the courts — was £1.12 billion, up 151% on the previous 12 months. Ware’s particular speciality of fraud is known as “double-financing”: he either borrowed from multiple lenders against the same development without them finding out that the building effectively belonged to someone else, or he sold the same plot of land to more than one person and pocket all the cash.

He had worked out how to manipulate the Land Registry, the system that is supposed to protect the buyers, sellers and those who lend against land or property deals in the UK. It was simple but also highly sophisticated, and it would fall to officers in the Merseyside Police Economic Crime Unit to stop him.

It’s Halloween following the trial and we’re sitting in a meeting room on the fourth floor of Police Headquarters. Detective Inspector Holly Chance pulls no punches about the conman she helped to lock up. “He presents as a narcissist,” she says. “In court, he was arrogant and showed a complete lack of empathy or consideration for the people he had used. He had no regard to the consequences of his actions.”

I ask why she believes so few fraud offences are reported. “There’s an obvious embarrassment around becoming a victim of fraud,” she says. “People who fall prey to con men like Robert Ware are usually intelligent and there’s a stigma around losing money to their scams. Many people would rather choose to suffer in silence than have anyone else know.”

DI Chance — who says much of her job is about crime prevention and education — joined the economic crime team in 2019 and took over as the senior officer on Operation Benadir investigating Ware. By this point, two people had been unpicking his complex conspiracy for more than two years.

One of them was Clive Myerscough, who retired in 2004 after 30 years on the force, only to rejoin Economic Crime 12 months later as a civilian investigator. He was the first to identify the hallmarks of a double-financing con as he dug his way through more than a hundred property transactions in search of a pattern. Myerscough sits in the room with us, listening intently in the way that only an investigator with nearly four decades of service can.

“Robert Ware liked the high life: the nice clothes, the Bentley and first class tickets to Dubai, and his victims helped fund that,” he says. “People lost their pensions, their jobs, and their reputations while he gained their trust and manipulated them.”

One lending institution stood to lose up to £7 million; another, £3 million. But the corporate lenders were not the only losers. The Land Registry was exposed to losses of more than £5 million, a tab that will ultimately be picked up by the taxpayer. The people who brought Robert Ware to justice believe his business plan was all about “trying to impress” and that it was greed that drove him on. It would take them six years to prove it in court.

“The public often sees massive fraud go undetected. Fraud has a corrosive effect on the public and our institutions.”

His Honour Judge Potter — R v Ware, 2023

As the mastermind behind the multi-million-pound conspiracy, Ware would identify buildings for sale in Liverpool that needed a lot of work, but could be worth much more when completed. He convinced people like Snow to lend him the cash to carry out the renovations and gave them a stake in the building as security in case the deal went sour. This security came in the form of a legally binding agreement that is called a “charge”, and it was supposed to be filed with the Land Registry after every deal was done.

At least, that was what the people who loaned him millions of pounds thought. But he had worked out that if he delayed filing the charges, he could buy himself the time to borrow even more money from someone else against the same buildings. Or he would simply sell the plot of land and pocket all the cash himself.

Although his con sounds straightforward, to pull it off took an intimate knowledge of how the Land Registry works. It also required an extreme betrayal of trust that left his lenders out of pocket and with no security. The court heard that between 2013 and 2017 he had successfully double-financed eight development schemes across the city and used his network of companies to launder the proceeds.

Covering legal proceedings can sometimes feel like watching good theatre, with the jury playing the role of an audience who must be won over. The reality is there’s rarely a powerful pivot point where the prosecution presents a piece of smoking-gun evidence to gasps from the courtroom. So it was in room 4:5 at Liverpool’s Queen Elizabeth II Court over those 12 long summer weeks of 2023. But while the numerous lever-arch files of documents, statements and evidence stacked up against him, it was the emails and text messages Robert Ware sent to his co-accused that shone the brightest light on this dark character. Ego would be his downfall.

Between his descriptions of comedowns following weekends away in Dubai “on the lemmo” (cocaine), Robert Ware coerced, cajoled and groomed his friend Jonathan Gorman into doing his bidding. Gorman is a former solicitor who had been struck off the roll in October 2020 for other Land Registry offences that he and Robert Ware had committed three years earlier. The fallout from Robert Ware’s legacy of lies created a snowball effect that also destroyed the Liverpool law firm EAD. They employed Jonathan Gorman and around 70 others, but the firm went down in 2017, sunk beneath an estimated £15 million loss linked to Ware’s property transactions. As their friendship began to strain under the weight of the police investigation, the ringleader bragged and tried to calm fears:

15/11/16

WARE: Stop worrying

GORMAN: Was worried over U. Speak to U tomorrow x

WARE: Nah, I have more front than Blackpool

WARE: 🙂

GORMAN: U do like

WARE: Vegas

My notes from this day in court read: “Prosecution reads out message exchange. Ware looks at Gorman … ear-to-ear grin. Gorman ignores. Ware stifles laughter”.

Nick Johnson KC for the prosecution was not laughing, and pressed to suggest the messages illustrated a pride at the way he used his “front” to groom lenders who placed their trust in him. But the conspiracy began to crumble. In one WhatsApp exchange with his partner at the time, Sally Ann Stanway, Ware writes about the arrest of Graham Wortley, his finance broker:

17/04/19 at 10:32

WARE: Graham lifted

SALLY: Why?

WARE: Connection with me

SALLY: 🙈

WARE: 😡

WARE: He will have had his fucking computer and phone so I’m fucked even though I told him not to

Graham Wortley fought back tears as he was convicted as the budding accomplice alongside Robert Ware, and was sentenced to six years for his part in the conspiracy. The jury found Jonathan Gorman not guilty. What they did not see was him arriving each day to court flanked by bodyguards — they were never told that Jonathan Gorman had been threatened, or of his belief in this need for protection.

Outside the courtroom, The Post’s investigation of Robert Ware has uncovered evidence that shows chances may have been missed to stop him sooner when he had been caught running the same scam back in 2009 but escaped prosecution. All solicitors are regulated and must follow a strict code of professional conduct. Allegations that they may have broken the rules are investigated by a panel of their peers who sit on the Solicitors’ Disciplinary Tribunal (SDT). The ultimate sanction the SDT can hand down is to remove the offending professional from the list of people permitted to practise law, known as “the roll”. Being removed is career suicide and a badge of dishonour that stays on the public record held by the Solicitors’ Regulatory Authority and the SDT forever.

In 2012, Robert Ware was called before a disciplinary tribunal which heard allegations of forgery and filing false documentation with the Land Registry. The misconduct hearing was told he had been qualified for less than a year before he had begun to bend the rules past breaking point. In mitigation and a call for their mercy, he told them in October 2012: “I now suffer from acute stress and other medical issues. I am only 31 and plan to have a life away from the Legal Profession after a lengthy time off.”

The tribunal found him guilty of offences almost identical to those that would eventually end with his eight-year jail term. But before they had a chance to issue their ultimate sanction and strike him off, Ware had voluntarily resigned from the solicitors’ roll. The panel believed his story that “mistakes” had been made because he was overworked and found no criminality. He was fined just £2,000.

In sentencing Ware for similar offences more than a decade later in 2023, Judge Potter would note: “You failed to respond to previous warnings about your behaviour and instead used that knowledge to further the fraud.”

Ware escaped with a token fine and continued to develop his con, but his dishonesty ran deeper than dodgy dealings with those who loaned him money. One of Ware’s many other victims was Paul Ponting. The businessman owns Danoli Telecoms, an IT company that installed the telephone and internet services in some of his properties. Ponting took the developer to court over an unpaid bill of £800, and in 2016, after Ware continued to ignore demands, he set up a thread on the “PubChat” internet forum. His posts raised awareness and appealed to other victims of Ware to add their stories. Ponting tells me he was “gobsmacked” after as many as 50 people came forward.

“We were starting to untangle his web of deceit,” he says. “The next thing, he phoned me up and told me he was going to ‘bite my fucking nose off’. He was threatening and trying to intimidate me into backing off.”

This short clip of the phone call is still on the PubChat thread, together with testimonials from other people who claim Ware ripped them off. Soon after debt collectors recovered Ponting’s money, his house was targeted with a firebomb. Before news of the attack was made public, Ponting claims he received an email from Ware to say he was “sorry to hear about the arson”. He was never investigated or prosecuted in relation to the fire damage, but soon he faced a different type of justice.

In August 2019, as Ware walked home from an evening out in Gateacre, drinking in his local pub, he was jumped and attacked. Armed officers found him in a pool of his own blood after they responded to reports of gunfire. He had been stabbed eight times. Police confirm bullet casings were also found at the scene. One officer told The Post the property developer’s life may have been saved that night by his terrible diet and lifestyle. He darkly joked that Ware avoided a more serious injury because he “always wore a stab-vest made of lard”.

“If he wasn’t so fat, it’s likely the blade would have gone much deeper,” says an anonymous police officer. “Wounds to his spleen, liver, kidneys and maybe his heart could have done a lot more damage.”

His attacker fled into the darkness and was never caught. But as part of their investigation into the stabbing, detectives ended up with Ware’s phone. Messages revealed a number of meetings with a man whose name was familiar to the Operation Benadir team: Stephen Rice. Rice had borrowed money to finance the purchase of a grand house on Linnet Lane, just back from Princes Park, but his property had been double financed. Despite the fact he stood to lose a small fortune, this crime went unreported because Rice had his own secrets to hide.

Between 2012 and 2016, Stephen Rice had amassed a property empire valued at £2.5 million through a series of deals with Robert Ware. While there’s no suggestion Rice was involved in any acts of criminality, there was a problem — he was also a Chief Inspector in Merseyside Police and he had failed to fully declare this lucrative side hustle.

In February 2023, Rice’s 24-year career came to a humiliating end. A gross misconduct hearing was told that when officers from Operation Benadir realised a senior colleague had been borrowing money from their prime suspect in the double financing scam, he was placed under surveillance.

The hearing for DCI Rice heard Ware was described on the force intelligence database as a “long-standing associate” of Desmond “Dessie” Baylis. Baylis was a local businessman who turned his hand to acting and specialised in playing gangsters. Baylis was one of the stars of the cult Liverpool film Shooters, but when his acting career dried up, he teamed up with real-life criminals.

In 2012, at the age of 41, Dessie Baylis was jailed for eight years for running one of Britain’s biggest cannabis factories in an operation that covered an area the size of two football pitches. The court heard he was part of an organised crime group that funded lavish lifestyles from the proceeds of crime. For a Merseyside Chief Inspector to be doing business with an associate of organised criminals put him at risk of blackmail and corruption. Rice was told his business relationship with Robert Ware had to end.

“Chief Inspector Rice is like Icarus,” said James Berry, a lawyer for Merseyside Police, in a misconduct hearing in February this year. “He has flown rather too close to the sun in terms of very attractive seeming property deals from which he could become fantastically well off, and forgetting his role as a police officer.”

The misconduct hearing was told that by 2017 Rice should have known of Robert Ware’s criminal connections and cut all contact. He was warned to stay away but instead he tipped his business partner off about the on-going police investigation, Operation Benadir. In one exchange recovered from Robert Ware’s phone from February 2018, the pair joked about meeting in disguise:

WARE: Should I wear a moustache, hat and gloves?

RICE: No. I’m wearing the floral dress and blonde wig.

In his defence, Chief Inspector Rice told his 2023 misconduct panel that the stress and pressure of losing nearly £600,000 on the Linnet Lane deal had led him into “making mistakes”. Those mistakes included a two-hour negotiation with a prisoner in HMP Garth who was using a mobile phone that had been smuggled into the jail. He also failed to declare that he owed Robert Ware £65,000.

Adding insult to injury, the panel found that a 20,000-word essay submitted as part of a master’s course in Police Leadership, part funded by the Merseyside Constabulary, had been a fake. Rice had bought the dissertation from a company called UK Essays for £3,300. On February 25th, 2023, Chief Inspector Stephen Rice was fired from the force in disgrace. His relationship with Robert Ware had ended his career and left his reputation in tatters.

One man who also knows just how much damage Robert Richard Herbert Ware can do is Chris Snow. His house is now mortgaged to the hilt, the family business is broken and he says there is little left to pass on to his son. He can barely bring himself to mention the name of the man who he once believed to be a good friend but who took so much from him.

“I blame him for my triple bypass,” says Snow. “He’s stolen our money, my health and nearly took my sanity. I was a fool to trust that man and I don’t know if I’ll ever trust anyone again.”

Comments

Latest

The ‘charisma bypass’: Why Liverpool’s leaders are so forgettable

The Mersey’s clean-up cost £8 billion. So why is it still so dirty?

Between Labour, Reform and Jeremy Corbyn, what does Liverpool’s electoral future look like?

Pete Burns wasn’t nice, kind, or fair. But he was unforgettable

A legacy of lies: The downfall of a Liverpool conman

'I hate Rob Ware and wish I’d never met him'